Medical abortion

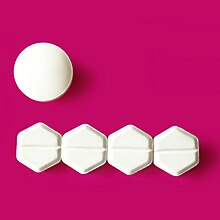

Appearance

A medical abortion, also known as medication abortion, occurs when drugs (medication) are used to bring about an abortion. Medical abortions are an alternative to surgical abortions such as vacuum aspiration or dilation and curettage. Medical abortions are more common than surgical abortions in most places, including Europe, India, China, and the United States.

Quotes

[edit]- Mifepristone may be the least marketed pharmaceutical product in the U.S. There aren’t any ads for it on TV. Most doctors can’t prescribe it. Pharmacists don’t know much about it, since it doesn’t sit on the shelves at CVS or Walgreens. It would be reasonable to assume this is all because mifepristone is exceptionally dangerous. But it sends fewer people to the ER than Tylenol or Viagra.

- Cynthia Koons, "The Abortion Pill Is Safer Than Tylenol and Almost Impossible to Get", Bloomberg.com (February 17, 2022; updated on May 3, 2022)

See also

[edit]- Abortion

- Abortion debate

- Definitions of abortion

- Christianity and abortion

- Enslaved women's resistance in the United States and Caribbean

- History of abortion

- Unsafe abortion