Unsafe abortion

An unsafe abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by people lacking the necessary skills, or in an environment lacking minimal medical standards, or both. An unsafe abortion is a life-threatening procedure. It includes self-induced abortions, abortions in unhygienic conditions, and abortions performed by a medical practitioner who does not provide appropriate post-abortion attention. About 25 million unsafe abortions occur a year, of which most occur in the developing world.

Quotes

[edit]- Kawana Ashley, an unwed, pregnant teenager, had reasons for wanting to terminate her pregnancy. Unfortunately for Ashely, she was twenty-five weeks pregnant and could no longer obtain a legal abortion because the fetus was viable. So, on March 27, 1994, she obtained a gun and shot herself across the abdomen in an attempt to terminate her pregnancy. Ashely was rushed to the hospital and survived her self-inflicted gunshot wound. Her fetus, however, had been struck by the bullet and died fifteen days later. Ashley was prosecuted for manslaughter and third-degree murder, but the Florida Supreme Court held that a pregnant woman cannot be charged with these crimes for self-aborting. The court held that, under Florida law, Ashley could self-abort at any time during her pregnancy, even when the fetus was viable.

- Alford, Suzanne M. (2003). "Is Self-Abortion a Fundamental Right?". Duke Law Journal. 52 (5): 1011–29. JSTOR 1373127. PMID 12964572. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- Where therapeutic abortion has not been available, women have used a variety of ineffective but often-life endangering agents to try to end a pregnancy. Among them are concentrated soap solution used as a douche, the insertion of suppositories of potassium permanganate and the ingestion of quinine pills, or of castor oil or other strong laxatives. None of these is an effective abortifacient.

- Christine Ammer; JoAnn E. Manson (February 2009). “The Encyclopedia of Women's Health”. Infobase Publishing. pp.1-2

- Women who are considering abortion should remember that the earlier it is performed, the safer it is. Many of the facilities (clinics) and physicians performing abortions offer a limited range of services, so it is important to investigate what is available. Such research can be done through local health departments, women’s health centers and clinics, and local Planned Parenthood associations, which usually have a referral list for their locality. Factors to consider in choosing a physician or service include preferences as to general or local anesthesia (general anesthesia is advisable only in a hospital), private or clinic care, impatient or outpatient care, the type of procedure desired, the availability of emergency care should it be needed and aftercare should complications develop.

- Christine Ammer; JoAnn E. Manson (February 2009). “The Encyclopedia of Women's Health”. Infobase Publishing. p.7

- Since the passing of the groundbreaking Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act in 1996 maternal mortality and morbidity related to unsafe abortion have been reduced by 91% and 50%, respectively, while recorded terminations of pregnancy (TOPs) increased by 67%.

TOPs at designated facilities rose steadily from 26 401 in 1997 (the year after the law was introduced) to 81 900 last year (67%).

These figures come from the national Department of Health and the Medical Research Council (Jewkes, et al.) as emphasis in the once hotly debated and much-ventilated topic shifts towards whether sufficient counselling is being offered to these women, 9.7% of whom are minors.

According to the latest Health Systems Trust data, the percentage of designated TOP facilities actually functioning rose from 31.5% in 2000 to 61.8% in 2003.

Izindaba enquiries showed the fault lines to have remained the same: ‘pro-lifers’ (such as Doctors for Life (DFL)) versus organisations like the Reproductive Rights Alliance (formed to promote the legislation) – arguing a shameful paucity versus a mostly pragmatic sufficiency of counselling.- Bateman C (December 2007). "Maternal mortalities 90% down as legal TOPs more than triple". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 97 (12): 1238–1242. PMID 18264602. p.1238

- ‘Our view is that if more people can come together and help a province provide this service, it’s one way of cutting down on backstreet abortions and helping often desperate women.’

Theron said he was aware of complaints about the lack of counselling at over-stretched public clinics – which made such public/private TOP partnerships all the more valuable.

Marie Stopes clinics were ‘coping comfortably’ with the extra work and maintained public awareness by visiting midwives at state clinics and reminding them of the free referral facility wherever it existed.

Even where a public-private partnership did not exist, provincial TOP facilities sometimes referred patients to them. ‘Those that can afford to use us under 12 weeks get help immediately – we can go up to 20 weeks, after which we refer to a private gynae.’

He had come across ‘dilemmas’ of women who could not be helped timeously at state facilities. By the time they could be seen to, they were ‘too far advanced’, making termination illegal.

Trueman said one of the more worrying complaints among midwives involved the cavalier prescribing or dispensing of misoprostol (Cytotec) (a cervical ripening agent) by persons who had no relationship with any designated TOP facility. ‘These cases get treated as incomplete abortions in hospital and they end up going for a D and C – in most provinces you’ll find midwives very uptight about this,’ she added.

These women were often not afforded counselling to the same extent as they would be if they were helped at TOP facilities, she said. Professor Denise White, deputy chairperson of the South African Medical Association, advised GPs to refer patients to the appropriate facilities, adding that any doctors behaving as alleged would be putting themselves and their patients at ‘huge risk’.

‘We’re living in an enlightened era where legitimate resources are available. This is an ethical and medico-legal issue and we don’t want to hark back to the era of backstreet abortions.’

White said no substantive evidence had emerged that doctors were prescribing the ripening agents without providing referral or further support and it would be ‘very concerning if non-registered charlatans’ were behind the phenomenon, as suggested by Ruschebaum.- Bateman C (December 2007). "Maternal mortalities 90% down as legal TOPs more than triple". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 97 (12): 1238–1242. PMID 18264602. pp.1240-1241

- Unsafe abortion and associated morbidity and mortality in women are completely avoidable. This paper reports on an analysis of the association between legal grounds for abortion in national laws and unsafe abortion, drawing on an unpublished study and using estimates of the incidence of and mortality from unsafe abortion using information from the sources used to estimate the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. Although legal grounds alone may not reflect the way in which the law is applied, nor the quality of services offered, a clear pattern was found in more than 160 countries indicating that where legislation allows abortion on broad indications, there is a lower incidence of unsafe abortion and much lower mortality from unsafe abortions, as compared to legislation that greatly restricts abortion. The data also show that most abortions become safe mainly or only where women's reasons for abortion, and the legal grounds for abortion coincide. This is a compelling public health argument for making abortion legal on the broadest possible grounds. A wide range of actions have formed part of national campaigns for safe, legal abortion over the past century, covering law reform, provision of safe services, ensuring quality of care, training for providers and information and support for women. Safe abortion is an essential health service for women, as essential for sexual and reproductive health as safe contraception, and safe pregnancy and delivery care. In spite of sometimes powerful opposition and terrible setbacks, the public health imperative is gaining ground in many parts of the globe.

- Berer M (November 2004). "National laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change". Reproductive Health Matters. 12 (24 Suppl): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24024-1. PMID 15938152. S2CID 33795725.

- Twenty-five states have enacted Targeted Restrictions on Abortion Providers —or TRAP — laws imposing strict requirements on abortion clinics and providers that the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research group, says "go beyond what is necessary to ensure patients’ safety." Reproductive rights activists also call them "clinic shutdown laws," because they say the laws are often written with the intent of closing abortion clinics in the state.

- Business Insider, (February 10, 2017). "Here's how many abortion clinics are in each state"

- A TRAP law was at the heart of a major case decided by the Supreme Court in 2015, Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt. The law in question required abortion clinics in Texas to meet strict standards, from the exact size of the examination rooms to admission privileges doctors had to secure for admitting patients to local hospitals.

In June, SCOTUS ruled in a 5-3 decision that the law "provides few, if any, health benefits for women, poses a substantial obstacle to women seeking abortions, and constitutes an 'undue burden' on their constitutional right to do so."

But similar laws are still on the books in half of the states in the country, and can cause clinics to close, forcing women who need abortions to travel farther in order to get the care they need. After Texas' law went into effect in 2013, the number of clinics providing abortions in the state dropped in half, from 41 to 22.- Business Insider, (February 10, 2017). "Here's how many abortion clinics are in each state"

- Death from illegal abortion was once common in the United States. In the 1940s, more than 1,0000 women died each year of complications from abortion. In 1972, 24 women died of complication of legal abortion and 39 died from known illegal abortions. In 2000, the last year for which complete data are available, there were 11 deaths from legally induced abortion, and no deaths from illegal abortion (abortion induced by a nonprofessional) in the entire United States. The American Medical Associations Council on Scientific affairs has reviewed the impact of legal abortion and attributes the decline in deaths during the country to the introduction of antibiotics to treat sepsis; the widespread use of effective contraception beginning in the 1960s, which reduced the number of unwanted pregnancies; and, more recently, the shift from illegal to legal abortion. The United States has a serious problem with teenage pregnancy. Without legal abortion, there would be almost twice as many teenage births each year.

- Sacheen Carr-Ellis, Nathalie Kapp; "10. Family Planning". In Berek, Jonathan S. (ed.). "Novak's Gynecology” (14 ed.). (2007) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp.295-296

- It is the number of maternal injuries and deaths, not abortions, that is most affected by restrictive legal codes. Abortions performed outside the law have a higher rate of complications and deaths, the majority of which are entirely preventable. Worldwide, more than one third of the estimated 50 million annual abortions are illegal abortions, occurring mainly in the developing world. Researchers estimate that 70,000 to 200,000 women a year around the world die from illegal and unsafe abortions. Doing away with such purposeless human suffering has been one of the main motives behind the movement to liberalize abortion laws the world over.

At present almost two thirds of the world’s women live in countries where abortion may be legally obtained for a broad range of social, economic or personal reasons. When abortion is made legal, available and safe, women’s reproductive health improves. Abortion-related mortality is reduced by at least 25% and related illness by far more. Where abortions are safe and affordable, by far the largest percentage of women terminate their pregnancies within the first trimester.

When women can avoid births which are unwanted, mistimed, or too numerous, their children are more likely to survive and be healthy. The incidence of infanticide and child abandonment typically go down when abortion is legalized.

Even in countries where the abortion law seems “liberal”, it cannot be assumed that every woman has an equal chance of getting an early, safe abortion if she needs one. Lack of medical facilities or personnel, women’s low status in society, cultural taboos, restrictive regulations and financial roadblocks can effectively curtail access to legal abortion and contraception, especially for disadvantaged and young, unmarried women. Changes in laws, while necessary, are not themselves sufficient for widespread access to family planning and safe abortion services.- "Abortion Law, History & Religion". Childbirth By Choice Trust. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- The latest World Health Organization data estimate that the total number of unsafe abortions globally has increased to 21.6 million in 2008. There is increasing recognition by the international community of the importance of the contribution of unsafe abortion to maternal mortality. However, the barriers to delivery of safe abortion services are many. In 68 countries, home to 26% of the world's population, abortion is prohibited altogether or only permitted to save a woman's life. Even in countries with more liberal abortion legal frameworks, additional social, economic, and health systems barriers and the stigma surrounding abortion prevent adequate access to safe abortion services and postabortion care. While much has been achieved to reduce the barriers to comprehensive abortion care, much remains to be done. Only through the concerted action of public, private, and civil society partners can we ensure that women have access to services that are safe, affordable, confidential, and stigma free.

- Culwell, Kelly R.; Hurwitz, Manuelle (May 2013). "Addressing barriers to safe abortion". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 121: S16–S19. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.02.003. PMID 23477700. S2CID 22430819.

- Unsafe abortion accounts for a significant proportion of maternal deaths, yet it is often forgotten in discussions around reducing maternal mortality. Prevention of unsafe abortion starts with prevention of unwanted pregnancies, most effectively through contraception. When unwanted pregnancies occur, provision of safe, legal abortion services can further prevent unsafe abortions. If complications arise from unsafe abortion, emergency treatment must be available.

- Culwell KR, Vekemans M, de Silva U, Hurwitz M (July 2010). "Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 110: S13–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.003. PMID 20451196. S2CID 40586023.

- Unsafe abortion is one of the most neglected public health challenges in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where an estimated one in four pregnancies are unintended—wanting to have a child later or wanting no more children. Many women with unintended pregnancies resort to clandestine abortions that are not safe. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 1.5 million abortions in MENA in 2003 were performed in unsanitary settings, by unskilled providers, or both. Complications from those abortions accounted for 11 percent of maternal deaths in the region.

- Dabash, Rasha; Roudi-Fahimi, Farzaneh (2008). "Abortion in the Middle East and North Africa" (PDF). Population Research Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2011. p.1

- The fact of the matter is that the distinction that the anti-choice movement seeks to make, between “life-saving” abortions and merely “health-saving” ones, is empirically impossible to determine: medical risks in pregnancy escalate quickly and unpredictably, meaning that a medical emergency can become life-or-death with little warning. It is unclear whether this fictional distinction is one the court will enshrine in law. But in another sense, the anti-choice movement has already won: the abortion debate now is being waged not on questions of women’s equality, dignity, and self-determination – these have already been sacrificed by the law as supposedly incompatible with the status of pregnancy.

What is at stake now – what was being debated in court on Wednesday – is how much women can be forced to suffer, how much danger they can be placed in. The anti-choice movement, and its allies on the bench, have shown once again that there is no amount that will satisfy them.- Moira Donegan, “The US supreme court heard one of the most sadistic, extreme anti-abortion cases yet”, The Guardian, (25 April, 2024)

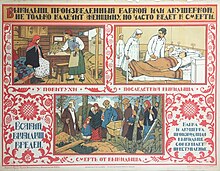

- In colonial times, surgical abortions were so dangerous, women almost never survived them. But many substances to bring about abortions were known. Depending on the amount used, these could accidentally kill both the mother and the fetus, kill only the fetus, or fail to work at all.

- Farrell, Courtney (2008). “Abortion Debate”. ABDO Publishing Company. Abortion From Past to Present, p.20

- Illegal abortion is responsible for up to half of maternal deaths and consumes a large proportion of health resources in many developing countries, particularly in Africa and Latin America. The legal situation of abortion in a country does not influence the abortion rate, but illegality is associated with a much greater risk of complications and death. To make abortion legal is not enough. Access to safe abortion strongly depends on the capacity and willingness of physicians and the health system to provide safe services, which sometimes are made available in spite of restrictive laws. The abortion rate will drop and the safety of the procedure will improve, parallel to the position women occupy in a given society, and to the level of recognition of their sexual and reproductive rights. The medical profession, and FIGO in particular, has a great role to play in implementing initiatives that will reduce the consequences of illegal abortion for women and society.

- A Faúndes, E Hardy; “Illegal abortion: consequences for women's health and the health care system”, Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997 Jul;58(1):77-83.

- Unsafe abortion is preventable, but it remains a major global health issue causing unnecessary threats to women’s health and burdens on the health system. Globally, an estimated 25 million abortions (45% of the total 55.7 million) that occur every year are unsafe, with most (97%; 24 million) occurring in low‐resource settings where countries that highly restrict abortion are concentrated. Unsafe abortion results in an estimated 47,000 maternal deaths a year, and an additional 6.9 million women are estimated to suffer morbidities from complications due to unsafe abortion. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines unsafe abortion as a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy carried out by either a person lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both. Since 2000, with the advent and ubiquitous access to medical abortion drugs, safe abortion has increased, and abortion‐related morbidity and mortality have improved.

- Gambir, Katherine; Kim, Caron; Necastro, Kelly Ann; Ganatra, Bela; Ngo, Thoai D. (9 March 2020). "Self-administered versus provider-administered medical abortion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD013181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013181.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7062143. PMID 32150279.

- In 1881 the Michigan Board of Health estimated one hundred thousand abortions a year in the United States, with just six thousand deaths, or a 6 percent mortality rate. There is some misunderstanding about abortion safety today because the campaign for legalized abortion has understandably emphasized the dangers of illegal abortion. In fact, illegal abortions in this country have an impressive safety record. The Kinsey investigators, for example, were impressed with the safety and skill of the abortion they surveyed. Studies of maternal mortality in the late 1920s and early 1930s found that 13-14 percent resulted from illegal abortion (meaning, of course, that 86-87 percent resulted from child-birth). Legal abortion had made that ratio even more uneven today in the United States, when eleven times more women die in childbirth than from abortions.

This does not mean that abortions were pleasant. They were painful and frightening, and anxiety was worse because they were “gotten in sin” and, often, in isolation. The physical risk was heightened by the illegality, just as it is today.- Gordon, Linda (2002). “The Moral Property of Women”. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02764-7. “Ch.2 The Criminals” p.25

- When the medical establishment undertook a campaign against abortion in the second half of the nineteenth century, its very vehemence served as a further indication of the prevalence of illegal abortions. In 1857 the American Medical Association (AMA) initiated a formal investigation of the frequency of abortion. Seven years later the AMA offered a prize for the best popular antiabortion tract. Medical attacks on abortion grew in number and virulence until, by the 1870s, both professional and popular journals were virtually saturated with the issue. Physicians bemoaned the widespread lay acceptance of abortion before quickening; in order to break that sympathy, they adopted a new vocabulary that described abortion in terms designed to shock and repel, such as “antenatal infanticide.” Physicians attempted to frighten women away from abortion by emphasizing its dangers. Their common assertion that there was “no” safe abortion may have betrayed ignorance, but more likely it was an exaggeration justified by what they believed was a higher moral purpose. Yet occasionally even antiabortion doctors allowed the truth to slip out, revealing despite themselves why their campaign remained ineffective. It is such a simple and comparatively safe matter for a skillful and aseptic operator to interrupt an undesirable pregnancy at an early date,” wrote Dr. A. L. Benedict of Buffalo, New York, an opponent of abortion, “That the natural temptation is to comply with the request.

- Gordon, Linda (2002). “The Moral Property of Women”. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02764-7. “Ch.2 The Criminals” p.30

- It is estimated that in 2000 27 million legal and 19 million illegal abortions were performed worldwide. Up to 95% of illegal abortions (unsafe abortions) were performed in developing countries and 99% of deaths from these abortions also occurred in those countries. Access to safe abortion is limited in many developing countries because of legal restrictions, administrative barriers to access legal abortion services, financial barriers and lack of adequately trained providers, In Latin America, rural women with limited financial resources disproportionately suffer from complications of illegal abortion.

- Grossman D (3 September 2004). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion: RHL commentary". Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- Although abortion is legal in every state, it is not easily accessible everywhere. Anti-abortion activists and legislators have managed to drive some abortion clinics out of business, a strategy that effectively functions as a state-level ban in places with few abortion providers. Mississippi is a case in point; in 2012, the state nearly lost its only abortion clinic due to a law requiring abortion providers to be "certified obstetrician/gynecologists with privileges at local hospitals." At the time, just one doctor at Jackson Women's Health Organization had these privileges.

Seven years after Mississippi's sole abortion clinic fought to stay open, the fate of Missouri's only such clinic hung in the balance because of a licensing dispute. In early 2019, Missouri's health department failed to renew the clinic’s license, arguing that the facility was out of compliance. Planned Parenthood opposed this decision, but the clinic's future remained uncertain and tied up in the courts, as of fall 2019. In addition to Missouri and Mississippi, four other states—Kentucky, West Virginia, North Dakota, and South Dakota—have just one abortion clinic.

The reasons several states have just one abortion clinic stems from Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws. This legislation limits abortion clinics through complex and medically unnecessary building requirements or by requiring providers to have admitting privileges at local hospitals—the case in Mississippi in 2012. Other laws, specifically those that require ultrasounds, waiting periods, or pre-abortion counseling, pressure women to reconsider ending their pregnancies.- Tom Head, “Is Abortion Legal in Every State?”, Thoughtco, (October 27, 2019)

- Until the late 19th century, abortion was legal in the United States before “quickening,” the point at which a woman could first feel movements of the fetus, typically around the fourth month of pregnancy.

Some of the early regulations related to abortion were enacted in the 1820s and 1830s and dealt with the sale of dangerous drugs that women used to induce abortions. Despite these regulations and the fact that the drugs sometimes proved fatal to women, they continued to be advertised and sold.- History.com Editors, "Roe v. Wade". HISTORY. (Updated: May 15, 2019 Original: Mar 27, 2018)

- While American women with the financial means could obtain abortions by traveling to other countries where the procedure was safe and legal, or pay a large fee to a U.S. doctor willing to secretly perform an abortion, those options were out of reach to McCorvey and many other women.

As a result, some women resorted to illegal, dangerous, “back-alley” abortions or self-induced abortions. In the 1950s and 1960s, the estimated number of illegal abortions in the United States ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year, according to the Guttmacher Institute.- History.com Editors, "Roe v. Wade". HISTORY. (Updated: May 15, 2019 Original: Mar 27, 2018)

- Overall, there was a significant increase in the proportion of cases with no signs of infection on admission (from 79.5% to 90.1%) and a significant decrease in evidence of interference on evacuation (4.5% to 0.6%) between 1994 and 2000. Substantial age differentials were seen. Women over 30 were significantly less likely than those 21-30 years or under 21 to be low severity (65.5% vs 75.2% vs 76.4%, P= 0.0087) and more likely to have offensive products (16.3% vs 6.0% vs 6.4%, P= 0.01) than the younger women.

Conclusions: Legalisation of abortion had an immediate positive impact on morbidity, especially in younger women. This is an important change as teenagers had the highest morbidity in 1994. The trend is supported by evidence from the 1999-2001 Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths, which further suggested that abortion mortality dropped by more than 90% since 1994.- Jewkes R, Rees H, Dickson K, Brown H, Levin J (March 2005). "The impact of age on the epidemiology of incomplete abortions in South Africa after legislative change". BJOG. 112 (3): 355–359. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00422.x. PMID 15713153. S2CID 41663939.

- Under the WHPA, prohibiting a state regulation requires nothing more than a “reasonable likelihood” that it might “indirectly” deter “some patients” from getting an abortion. Defending that regulation, however, requires “clear and convincing evidence” that the regulation “significantly advances the safety of abortion services” and that this goal “cannot be advanced by a less restrictive alternative measure or action.” How’s that for heads-the-pregnant-person-wins-tails-the baby-loses?

- Jipping, Thomas (February 28, 2022). "Women's Health Protection Act: Unconstitutional and More Radical Than Roe v. Wade". The Heritage Foundation. Archived

- Unsafe abortion has been identified as one of the most easily preventable causes of maternal ill-health and death, yet it continues to threaten the health and lives of women globally. This has led some commentators to declare that ‘ending the silent pandemic of unsafe abortion is an urgent public-health and human-rights imperative’ (Grimes et al 2006). In response to the issues and challenges raised by this situation, the WHO (2004, 2007b) has deemed ‘preventing unsafe abortion’ a strategic priority underpinned by the following two goals:

in circumstances where abortion is not against the law, to ensure that abortion is safe and accessible

in all cases, women should have access to quality services for the management of complications arising from abortion.- Johnstone, Megan-Jane (2009). “Bioethics a nursing perspective”. Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses Journal. 3 (5th ed.). Sydney, NSW: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p.228. ISBN 978-0-7295-7873-8. PMID 2129925. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- Although modern induced abortion is one off the safest medical procedures available, it is regulated like no other area of medicine in the USA. The procedure is currently subject to a multitude of federal and state laws and regulations. This situation was not always the case. From the country’s inception up through the first half of the 19th century, abortion prior to “quickening” was legal and largely unregulated in the USA.

- Bonnie Scott Jones, Jennifer Dalven, “Abortion law and policy in the USA” Ch.4 in Paul M, Lichtenberg ES Borgatta L Grimes DA Stubblefield P Creinin (eds) “Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care”. (April 27, 2009) Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Nearly 8% of maternal deaths worldwide are abortion-related and 99.5% of these occurring in developing regions. There is strong evidence linking unsafe abortions with increased maternal morbidity and mortality and most abortion-related maternal deaths are due to unsafe and illegal abortions. Although the overall abortion rate has declined, the proportion of unsafe abortions is increasing, especially in developing regions. Unsafe abortions are most common in countries with restrictive abortion laws. This suggests that improving abortion law reform could reduce maternal mortality, however, we do not have a rigorous evidence-base on which to support this premise.

- Latt, Su Mon; Milner, Allison; Kavanagh, Anne (5 January 2019). "Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries". BMC Women's Health. 19 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y. ISSN 1472-6874. PMC 6321671. PMID 30611257.

- On the 'health risks' of abortion....

*The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guideline, The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion, provides evidence based on systematic literature reviews to show that abortion cannot be considered a serious risk to women's physical or mental health.

*Claims by opponents of abortion that abortion leads to breast cancer, future infertility, or mental ill-health can be understood as a political strategy, not an objective evaluation of the likely effects of abortion for a woman's health.- Lee, Ellie; Ann Furedi (February 2002). "Abortion issues today – a position paper" (PDF). Legal Issues for Pro-Choice Opinion – Abortion Law in Practice. University of Kent, Canterbury, CT2 7NY, UK. pp.2-3 Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- Notwithstanding involvement on the part of Catholic and Protestant clergy and others, physicians were the leading force in the campaign to criminalize abortion in the USA. The American Medical Association (AMA), founded in 1847, argued that abortion was both immoral and dangerous, given the incompetence of many practitioners at that time. According to a number of scholars, the AMA’s drive against abortion formed part of a larger and ultimately successful strategy that sought to put “regular” or university-trained physicians in a position of professional dominance over the wide range of “irregular” clinicians who practiced freely during the first half of the 19th century.

What followed was a “century of criminalization” characterized by a widespread culture of illegal abortion provision. Thousands of women died or sustained serious injuries at the hands of the infamous “back alley butchers” of that period, and encountering these victims in hospital emergency rooms became a nearly universal experience for US medical residents. However, safe abortions were available to some women, performed by highly skilled laypersons and physicians with successful mainstream practices who were motivated primarily by the desperate situations of their patients. These “physicians of conscience” were instrumental in convincing their medical colleagues of the necessity to decriminalize abortion. By 1970, the AMA reversed its earlier stance and called for the legalization of abortion.- Paul, M; Lichtenberg, ES; Borgatta, L; Grimes, DA; Stubblefield, PG; Creinin, MD; Joffe, Carole (2009). "1. Abortion and medicine: A sociopolitical history" (PDF). Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy (1st ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1293-5. OL 15895486W. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. p.2

- Abortion legislation is another issue of primary concern in promoting reproductive health. Globally there are around 33 million legal abortions performed annually. It is estimated that illegal abortions contribute further to make a total of between 40 and 60 million. This means that for every known pregnancy there are between 24 and 32 induced abortions. It was estimated that in 2000 unsafe abortion accounted for a death toll of 68,000. Based on the 2000 figures it is estimated that 19 million unsafe abortions take place every year and that 1 in 270 such abortions result in maternal death.

- Maclean, Gaynor (2005). "XI. Dimension, Dynamics and Diversity: A 3D Approach to Appraising Global Maternal and Neonatal Health Initiatives". In Balin, Randell E. (ed.). Trends in Midwifery Research. Nova Publishers. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-59454-477-4. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015.

- Unsafe abortion continues to be a major public health problem in many countries. A woman dies every eighth minute somewhere in a developing country due to complications arising from unsafe abortion. She was likely to have had little or no money to procure safe services, was young – perhaps in her teens – living in rural areas and had little social support to deal with her unplanned pregnancy. She might have been raped or she might have experienced an accidental pregnancy due to the failure of her contraceptive method she was using or the incorrect or inconsistent way she used it. She probably first attempted to self-induce the termination and after that failed, she turned to an unskilled, but relatively inexpensive, provider. This is a real life story of so many women in developing countries in spite of the major advancements in technologies and in public health.

- Halfdan Mahler, (25 September 2007); "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). Preface, World Health Organization. (2007).

- One of the most easily preventable causes of maternal death and ill-health is unsafe abortion, which causes approximately 13% of all deaths and approximately 20% of the overall burden of maternal death and long-term sexual and reproductive ill-health.and reproductive ill-health.

- Halfdan Mahler, (25 September 2007); "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). Preface, World Health Organization. (2007).

- Every year nearly 42 million women faced with an unplanned pregnancy decide to have an abortion, and about 20 million of them are forced to resort to unsafe abortion. These approximately 20 million women often self-induce abortions or obtain a clandestine and unsafe abortion carried out by untrained persons under poor hygienic conditions. Abortion induced by a skilled provider in situations where it is legal is one of the safest procedures in contemporary medical practice and the recourse to manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) and medical (non-surgical) abortion have reduced abortion-related complications to very low levels.

- Halfdan Mahler, (25 September 2007); "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). Preface, World Health Organization. (2007).

- The interventions to prevent unsafe abortion include expanding access to modern contraceptive services, providing safe abortion to the full extent of the law, and tackling the legal and programmatic barriers to the access to safe abortion. An informed and objective discourse continues to be much needed for developing interventions to prevent unsafe abortion and its devastating consequences for the survival, health and well-being of women, families and societies. By providing an objective assessment of the incidence of unsafe abortion and its related mortality, this report goes a long way in raising awareness of this major, but often neglected, public health problem.

- Halfdan Mahler, (25 September 2007); "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). Preface, World Health Organization. (2007).

- Two folk medical conditions, "delayed" (atrasada) and "suspended" (suspendida) menstruation, are described as perceived by poor Brazilian women in Northeast Brazil. Culturally prescribed methods to "regulate" these conditions and provoke menstrual bleeding are also described, including ingesting herbal remedies, patent drugs, and modern pharmaceuticals. The ingestion of such self-administered remedies is facilitated by the cognitive ambiguity, euphemisms, folklore, etc., which surround conception and gestation. The authors argue that the ethnomedical conditions of "delayed" and "suspended" menstruation and subsequent menstrual regulation are part of the "hidden reproductive transcript" of poor and powerless Brazilian women. Through popular culture, they voice their collective dissent to the official, public opinion about the illegality and immorality of induced abortion and the chronic lack of family planning services in Northeast Brazil. While many health professionals consider women's explanations of menstrual regulation as a "cover-up" for self-induced abortions, such popular justifications may represent either an unconscious or artful manipulation of hegemonic, anti-abortion ideology expressed in prudent, unobtrusive and veiled ways. The development of safer abortion alternatives should consider women's hidden reproductive transcripts.

- Nations MK, Misago C, Fonseca W, Correia LL, Campbell OM (June 1997). "Women's hidden transcripts about abortion in Brazil". Social Science & Medicine. 44 (12): 1833–1845. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00293-6. PMID 9194245.

- Reagan's discussion of "dying declarations" makes particularly chilling reading: because the words of the dying are legally admissible in court, women on their deathbeds were informed by police or doctors of their imminent demise and harassed until they admitted to their abortions and named the people connected with them—including, if the woman was unwed, the man responsible for the pregnancy, who could be arrested and even sent to prison. In 1902 the editors of the Journal of the American Medical Association endorsed the by then common policy of denying a woman suffering from abortion complications medical care until she "confessed"—a practice that, Reagan shows, kept women from seeking timely treatment, sometimes with fatal results. In the late 1920s some 15,000 women a year died from abortions.

- Katha Pollitt, "Abortion in American History", Atlantic Monthly. (May 1997).

- The American Medical Association endorsed legalized abortion in 1967. Medical professionals reported that each year they were treating thousands of women who had obtained illegal abortions and had been injured as a consequence. Believing that abortions were inevitable in American society, they argued that legalizing the practice would allow trained medical staffs to perform safe procedures in medical facilities.

- Claire E. Ramussen, “Abortion”; in Chapman, Roger. “Culture wars: an encyclopedia of issues, viewpoints, and voices", M.E. Sharpe. Inc, (2010) pp.1-2

- Since TRAP laws surfaced in 2010, more than 50 safe abortion clinics have closed.

- Rankin, Lauren, "The Seven Most Common Lies About Abortion", Rolling Stone, (February 26, 2014).

- Access to safe abortion services is an urgent need in the developing world as well, particularly in countries throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where an estimated 68,000 deaths occur each year due to unsafe abortion procedures. Many more women (20 to 50% of those undergoing unsafe abortion) suffer from life-threatening complications. All too often those who survive are permanently scarred by these procedures that take place in hazardous and unsanitary conditions.

- Allan Rosenfield, “Introduction” In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES Borgatta L Grimes DA Stubblefield P Creinin (eds) “Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care”. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-7696-5. p.35

- Unsafe abortions cause 50,000 to 100,000 deaths each year. In some countries complications of unsafe abortion cause the majority of maternal deaths, and in a few they are the leading cause of death for women of reproductive age. The World Health Organization estimates that as many as 20 million abortions each year are unsafe and that 10% to 50% of women who undergo unsafe abortion need medical care for complications. Also, many women need care after spontaneous abortion (miscarriage). In one country, for example, at 86 hospitals an estimated 28,000 women seek care for complications of unsafe or spontaneous abortion each month.

The five main causes of maternal mortality are hemorrhage, obstructed labor, infection, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and complications of unsafe abortion. Many countries are undertaking programs to reduce deaths from the other four causes, but few provide adequate emergency medical care that would reduce maternal deaths from abortion complications. Even fewer provide family planning services and counseling to women treated for abortion complications.- Salter, C.; Johnson, H.B.; Hengen, N. (1997). "Care for Postabortion Complications: Saving Women's Lives". Population Reports. Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. 25 (1). Archived from the original on 7 December 2009.

- Only a small proportion of deaths are estimated to result from abortion in eastern Asia (0•8%, 0•2–2•0), where access to abortion is generally less restricted. Latin America and the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa have a higher proportion of deaths in this category than the global average; 9•9% (8•1–13•0) and 9•6% (5•1–17•2), respectively. Another direct cause, embolism, accounted for more deaths than its global average in southeastern Asia (12•1%, 3•2–33•4) and eastern Asia (11•5%, 1•6–40•6).

The proportion of deaths due to indirect causes was highest in southern Asia (29•3%, 12•2–55•1), followed by sub-Saharan Africa (28•6%, 19•9–40•3). Indirect causes also accounted for nearly a quarter of deaths in the developed regions. The overall proportion of HIV maternal deaths is highest in sub-Saharan Africa, 6•4% (4•6–8•8%). The appendix shows estimates for country-specific cause of death distributions.- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. (June 2014). "Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis". The Lancet. Global Health. 2 (6): e323–e333. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. PMID 25103301.

- Background: Information on incidence of induced abortion is crucial for identifying policy and programmatic needs aimed at reducing unintended pregnancy. Because unsafe abortion is a cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, measures of its incidence are also important for monitoring progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. We present new worldwide estimates of abortion rates and trends and discuss their implications for policies and programmes to reduce unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion and to increase access to safe abortion.

Methods: The worldwide and regional incidences of safe abortions in 2003 were calculated by use of reports from official national reporting systems, nationally representative surveys, and published studies. Unsafe abortion rates in 2003 were estimated from hospital data, surveys, and other published studies. Demographic techniques were applied to estimate numbers of abortions and to calculate rates and ratios for 2003. UN estimates of female populations and livebirths were the source for denominators for rates and ratios, respectively. Regions are defined according to UN classifications. Trends in abortion rates and incidences between 1995 and 2003 are presented.

Findings: An estimated 42 million abortions were induced in 2003, compared with 46 million in 1995. The induced abortion rate in 2003 was 29 per 1000 women aged 15-44 years, down from 35 in 1995. Abortion rates were lowest in western Europe (12 per 1000 women). Rates were 17 per 1000 women in northern Europe, 18 per 1000 women in southern Europe, and 21 per 1000 women in northern America (USA and Canada). In 2003, 48% of all abortions worldwide were unsafe, and more than 97% of all unsafe abortions were in developing countries. There were 31 abortions for every 100 livebirths worldwide in 2003, and this ratio was highest in eastern Europe (105 for every 100 livebirths).

Interpretation: Overall abortion rates are similar in the developing and developed world, but unsafe abortion is concentrated in developing countries. Ensuring that the need for contraception is met and that all abortions are safe will reduce maternal mortality substantially and protect maternal health.- Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH (October 2007). "Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide". Lancet. 370 (9595): 1338–1345. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.4197. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. PMID 17933648. S2CID 28458527.

- Results: Each year 42 million abortions are estimated to take place, 22 million safely and 20 million unsafely. Unsafe abortion accounts for 70,000 maternal deaths each year and causes a further 5 million women to suffer temporary or permanent disability. Maternal mortality ratios (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) due to complications of unsafe abortion are higher in regions with restricted abortion laws than in regions with no or few restrictions on access to safe and legal abortion.

Conclusion: Legal restrictions on safe abortion do not reduce the incidence of abortion. A woman's likelihood to have an abortion is about the same whether she lives in a region where abortion is available on request or where it is highly restricted. While legal and safe abortions have declined recently, unsafe abortions show no decline in numbers and rates despite their being entirely preventable. Providing information and services for modern contraception is the primary prevention strategy to eliminate unplanned pregnancy. Providing safe abortion will prevent unsafe abortion. In all cases, women should have access to post-abortion care, including services for family planning. The Millennium Development Goal to improve maternal health is unlikely to be achieved without addressing unsafe abortion and associated mortality and morbidity.- Iqbal Shah, Elisabeth Ahman; “Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges”, J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009 Dec;31(12):1149-58.

- Today, abortion practitioner in the United States are targeted and reviled by the radical right and isolated by their communities. Many wear bulletproof vests in public, and almost all have unlisted home telephone numbers. The need for such precautions is relatively recent. During the illegal era (from the mid-nineteenth century until 1973), abortion practitioners operated with varying degrees of secrecy, but they did not fear for their lives. In fact, a number of abortionists I the illegal era provided their services for years-twenty, thirty, forty years, and more-completely unimpeded by the law. In many communities, the local abortion practitioner’s name and address were well known, not only to women who might require the service but also to police and politicians, who generally regarded the presence of a good abortionist a public health asset. For decades after the American Medical Association worked with state legislatures in the nineteenth century to outlaw abortion, abortion prosecutions were rare relative to the number of abortions performed. In most communities an unwritten agreement prevailed between law enforcement and practitioners: no death, no prosecution.

But after World War II the old agreement was rather suddenly canceled, and practitioners-chiefly the female ones (presumed by law enforcement to be unskilled, untrained, and unprotected in comparison to their male counterparts, and therefore more likely to be convicted)-were arrested, convicted, and sent to jail in unprecedented numbers, even when there was no evidence of a botched abortion. Many of these practitioners were highly skilled and experienced, having performed twenty some abortions a day, year after year.- Solinger, Rickie (1998), "Introduction", in Solinger, Rickie (ed.), “Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950–2000”, University of California Press', pp.17-18

- Prior to scientific understanding of germ theory and antisepsis, any surgical intervention was likely to be fatal.

- Clyde Spillenger, Jane E. Larson and Sylvia A. Law; "Brief of 281 American Historians as Amici Curiae Supporting Appellees", "The Public Historian", Vol. 12, No. 3 (Summer, 1990), University of California Press, supra note 6, at 68.

- Various methods of unsafe abortion have been reported. In the pre-penicillin era, instrumentation or introductions of fluid into the uterus caused fatalities. These methods still prevail, with women attempting instrumentation into the uterus per vagina and rarely, per abdomen. There are also a number of reported cases where quinine, misoprostol, over-the-counter medicines, livestock droppings, detergent and herbal medicines have been used as abortifacients. Unsafe abortion can lead to morbidity and mortality. Complications range from minor infections to death; the more common being bleeding, infection, uterine perforation and peritonitis.

- Thapa, S.R.; Rimal, D.; Preston, J. (2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 697–98. PMID 16969439. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. p.697

- A lack of awareness of the associated complications and psychosocial state may be reasons why women choose unsafe methods of abortion. It is a difficult task to identify which women fall into such categories, however an effort should be made to avoid the implications of unsafe abortion at the primary health care setting where women approach for contraception and/or counselling on abortion. Therefore, the importance lies in educating and making women aware not only of the safe legal methods of termination of pregnancy, but also of the complications that could follow unsafe procedures.

- Thapa, S.R.; Rimal, D.; Preston, J. (2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 697–98. PMID 16969439. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. p.697-698

- Benefits and potential impact Has the potential to prevent nearly all deaths (70,000) and disabilities (5 million) from unsafe abortion annually.

*Saves an estimated.

US$680 million in health-system costs for treating serious complications due to unsafe abortion.

US$6 billion to treat post abortion infertility from unsafe abortion.

US$930 million to society and individuals in lost income due to death or disability resulting from unsafe abortion.

* Allows women and families to address consequences of contraceptive method failure.

- UNICEF; UNFPA; WHO; World Bank (2010). "Packages of interventions: Family planning, safe abortion care, maternal, newborn and child health". Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010. p.7

- ”All Governments and relevant intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations are urged to strengthen their commitment to women’s health, to deal with the health impact of unsafe abortion as a major public health concern and to reduce the recourse to abortion through expanded and improved family planning services.”

- September, 1994 U.N. International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo

- The theory that abortion can cause harm to women's mental health has also been refuted by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, and the American Psychological Association. But in determining that the medical associations had the right to sue based on what's known as third-party standing, Kacsmaryk also pointed to a 2011 meta-analysis by Priscilla Coleman that purported to show a link between abortion and mental health outcomes.

Dr. Ushma Upadhyay, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert in abortion access and safety in the U.S., criticized Coleman's methodology and said she compared wanted and unwanted pregnancies without accounting for the reasons that may contribute to whether a patient wants to get pregnant.

"Her work doesn't account for differences between groups when she looks at people who have had abortions and people who haven't," Upadhyay said. "It's so important because she will attribute the differences in mental health status to the abortion when it's clear as day that the differences in mental health status are due to a variety of life circumstances between the groups."- Melissa Quinn quoting Ushma Upadhyay, ”ACLU warns Supreme Court that lower court abortion pill decisions relied on "patently unreliable witnesses"”. CBS News, updated on: January 30, 2024

"Quantifying the global burden of morbidity due to unsafe abortion: magnitude in hospital-based studies and methodological issues" (September 2012)

[edit]Adler Alma J, Filippi Veronique, Thomas Sara L, Ronsmans Carine (September 2012). "Quantifying the global burden of morbidity due to unsafe abortion: magnitude in hospital-based studies and methodological issues". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 118 (Suppl 2): S65–S77. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60003-4. PMID 22920625. S2CID 43126015.

- The global burden of complications from unsafe abortion is thought to be high, but difficult to measure. A systematic review was conducted to describe the prevalence and type of complications of abortion among women hospitalized for treatment of abortion complications in settings where abortion is generally considered unsafe. There were 43 hospital-based studies reporting on severity and type of complications of abortions, but definitions varied substantially. The proportion of women treated in facilities for severe complications ranged from a median of 1.6% (range, 0.1%-10.8%) for renal failure to 7.2% (range, 0.1%-43.9%) for severe trauma. Heterogeneity of study designs and definitions makes comparisons difficult. Therefore, it is recommended that standardized designs and definitions are used in future studies of abortion complications.

- Unsafe abortion is thought to be widespread at the global level, although the exact burden is unknown. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines unsafe abortion as “a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy either by individuals without the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both”. According to this definition, the word unsafe refers to the standard of medical care rather than to complications resulting from unsafe procedures. Standards of medical care in relation to abortion procedures have not been clearly defined, however, and distinguishing between safe and unsafe environments remains difficult.

Many studies have attempted to quantify the numbers of women presenting at hospitals with complications of abortion. Such studies suggest that in developing countries, 5 million women may be admitted to hospitals each year as a result of an unsafe abortion. Few studies have examined the nature or severity of abortion complications, however, and it is difficult to interpret the magnitude of or variation in this reported burden. Some investigators have developed a systematic definition of severity of complications due to unsafe abortions, and it has been applied in a few countries. This definition has been recommended as a standard for future studies of severity of complications; however, relatively few studies have so far used this definition, and it is unclear whether there is a consensus on its use.

The objective of the present study was to review the literature to examine how the severity of abortion complications is defined in regions of the world where abortion is generally considered to be unsafe, and to synthesize what is known about the prevalence of severe abortion complications in women treated in facilities in these regions. A systematic review was conducted to determine the types and frequencies of complications reported to be associated with abortion, and methodological strengths and weaknesses of the available evidence are discussed. - Results

The search identified 14 475 citations. After titles and abstracts were screened, the full text for 1069 articles was obtained (Fig. 1). Forty-two studies provided information on specific complications of abortion in regions where abortion is generally considered unsafe. An additional study was obtained from an outside source, giving a total of 43 studies. Three studies reported two different study populations in their results, and these are reported separately in the tables. - Discussion

A total of 43 hospital-based studies were identified describing postabortion complications in regions where abortion is generally considered unsafe. Very few studies provided sufficiently detailed criteria to define complications, and definitions were particularly poor for hemorrhage and infections.

"Abortion among adolescents in Africa: A review of practices, consequences, and control strategies" (October 2019)

[edit]Shallon Atuhaire (October 2019). "Abortion among adolescents in Africa: A review of practices, consequences, and control strategies" (PDF). The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 34 (4): e1378–e1386. doi:10.1002/hpm.2842. PMID 31290183. S2CID 195871358. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-05-30.

- Background: Developing countries register 98% of unsafe abortion annually, 41% of which occur among women aged between 15 and 25 years. Additionally, 70% of hospitalizations due to unsafe abortion are among girls below 20 years of age.

Purpose: This study unveils abortion practices in Africa, its consequences, and control strategies among adolescents.- p.1

- Findings: These studies indicated that abortion is a neglected problem in health care in developing countries, and yet decreasingly safe abortion practices dominate those settings. Adolescents who have unintended pregnancies may resort to unsafe abortion practices due to socio-economic factors and the cultural implications of being pregnant before marriage and the legal status of abortion. Adolescents clandestinely use self-prescribed drugs or beverages, insert sharps in the genitals, and most often consult traditional service providers. Abortion results in morbidities such as sepsis, severe anaemia, disabilities, and, in some instances, infertility and death. Such events can be controlled by the widening availability of and accessibility to contraceptives among adolescents, advocacy, and comprehensive sexuality education and counselling.

Conclusion: Adolescents are more likely to use clandestine methods of abortion whose consequences are devastating, lifelong, or even fatal. Awareness and utilization of youth-friendly services would minimize the problem.- pp.1-2

- Approximately 56 million women of reproductive age undergo induced abortion annually, and of those, 22 to 25 million are unsafe2, contributing to 13% of maternal mortality cases worldwide. Developing countries register 98% of unsafe abortions annually, 41% of which occur among women aged between 15 and 25 years, and the highest ranking regions are Africa and Latin America.6 In Nigeria, over one-thirds of adolescents procure abortions, in Ghana, abortion is more prevalent among women ranging from 20 to 24 years, while this prevalence level is seen among women aged 20 to 29 years in other African countries. However, in Asia and Europe, women older than those in African countries undergo abortions.7 In Africa, an increasing rate of early sexual initiation and sexual coercion has been reported.8,9 More than one in three adolescents or young adults in Uganda between 15 and 24 years of age who are not married and who have never been married have had sexual contact. Another study conducted in Uganda indicated that 46% of adolescents had ever had sex, and 80% were not married. Because pregnancy carries different socio-cultural implications for unmarried adolescents than married women generally, those who unintentionally become pregnant may resort to unsafe methods of inducing abortion. Adolescents generally suffer a greater impact because they are vulnerable, have inadequate sexual and reproductive health information, and are unable to make firm choices. As such, a study by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF)11 noted that 70% of hospitalizations due to unsafe abortion complications were among women under 20 years of age. This finding makes this study worthwhile for the sake of documenting adolescent abortion practices, their consequences, and control strategies to inform stakeholders about the prevailing situation and to provide a basis for the necessary steps to improve adolescent health.

- p.2

- Abortion is generally defined as the expulsion of the conceptus before 28 weeks of gestation or before it weighs 500 g. Induced abortion could be safe or unsafe depending on the procedure taken, the environment in which it is carried out and the service provider. Therefore, safe abortion is one that is carried out by a trained provider following WHO recommended methods suitable for the gestational age. Unsafe abortion, on the other hand, is often carried out to terminate unintended or unwanted pregnancies by unskilled individuals and in an environment that does not meet minimum medical standards. Unsafe abortion is categorized by WHO into less safe and least safe. It is less safe when performed using old-fashioned means such as sharp curettage methods, even if by trained personnel, and/or if the individual performing the abortion has limited information regarding the methods and limited access to a skilled medical officer if required. It is least safe when it involves the ingestion of caustic substances, the use of harmful traditional inventions or the insertion of foreign bodies by untrained individuals.

- p.2

- Legal and safe abortion is 14 times safer than childbirth; however, until now, only three African countries have no restrictions regarding abortion, while 41 countries allow abortion to save the mother's life and maintain her physical and mental health, as well as for socio-economic aids. The law also permits induced safe abortion when the foetus is impaired or when the pregnancy was caused by defilement, rape, or incest; however, abortion is completely illegal in 10 African countries

- pp.2-3

- Abortions induced by oneself or by traditional healers, result in complications, with infections in 81.8% of women and haemorrhage in 68.2% of women, and in some instances, the process results in incomplete abortion. There are higher odds of such complications among unmarried adolescents and non-adolescents than among married women in both categories. Adolescents, especially students, are aware of safe abortion services but may not use them due to costs and associated stigma. Women who boldly seek safe abortion are highly stigmatized, as are the clinicians offering it. In fact, any discussion about the topic in developing countries is disrupted owing to its legal status, religious and moral values. Surprisingly, even health workers abuse, mistreat and stigmatize women who seek post-abortion care. Therefore, it is still a neglected problem in health care with inadequate information, and yet least safe and less safe abortion practices dominate these settings.

Mothers who unintentionally become pregnant opt for unsafe abortions due to the insufficiency and inaccessibility of safe abortion services, restrictive laws, high costs, and diligent objections by health care providers who observe the professional ethic of do not harm and due to insufficient knowledge of eligibility for safe abortion care. Nonetheless, in Asia and Europe, older women procure abortion mainly to limit or space births. Adolescents from African countries may particularly pursue abortions because of probable consequences such as stigmatization. It is often procured through clandestine measures and in unhygienic hidden places, offered by untrained practitioners. These abortions are generally unsafe, accounting for 21% of the maternal deaths that occur annually, making it an issue of public health importance in the region. Unveiling abortion practices, its consequences, and control strategies among adolescents is of great significance to policymakers, programme planners, and advocates. If the information provided is well utilized, it could lessen the incidence of unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and maternal and child mortality and morbidity, thus leading to a general increase in the number of healthy women.- p.3

- Africa has the highest rates of both intended and unintended pregnancies, standing at 136 and 86 per 1000 women of reproductive age, respectively. Central and East Africa registered the highest number of unintended pregnancies in 2010. Women who have unplanned pregnancies may opt for an abortion. In fact, one of every five of these women opts for abortion. In 2018, the Southern African region registered the highest abortion rate at 24%, followed by Northern Africa, Eastern Africa, Central Africa, and Western Africa at 23%, 14%, 13%, and 12%, respectively. However, in all regions, adolescents who are sexually active are more vulnerable than women older than 20 years of age with respect to their experiences and needs for and access to safe abortion care. First, they have a higher risk of unintended pregnancy and are unable to recognize it early compared to older women. Second, they are most likely to delay seeking an abortion for socio-economic and cultural reasons5 and, in some instances, due to policy-related and religious factors.

- p.3

- Abortion is generally more prevalent among women in urban centres globally than those in rural areas. However, rural residents in all age groups are more likely to use traditional methods than are urban residents. Unsafe abortions are also common among poorer, younger, and unmarried women with low socio-economic status than those who are married and/or well-off. Although adolescents undergo a substantial fraction of abortions, they are most frequently performed among women aged 20 to 29 years. Nonetheless, women below 20 years constitute more of those hospitalized for complications. A study conducted by Rasch and Kipingili in rural Tanzania also indicated that women who had an unsafe induced abortion were single, primigravida, and younger than 24 years of age. Women who procure unsafe abortions often use clandestine methods aided by unskilled attendants who may be a friend, a close relative or a traditional service provider. A study performed in Cote d'Ivoire in 2017 among high school students indicated that 70% of them first used a self-prescription, and in case it failed, 56.4% proceeded to use traditional service providers and whenever self-prescription and traditional methods were unsuccessful, approximately 85.7% of them consulted skilled health care providers as the last option. The students cited over-the-counter drugs, herbs, roots, beverages, and in some instances, the insertion of sharps in their genital tract as commonly used procedures. The use of pharmaceutical drugs, catheters, and roots has been cited by several other studies.

Some girls use battery acid, crushed bottles, pain medication, sedatives, anaesthesia, antibiotics, chlorine, white quinine, cassava-cyanide, aloe vera, castor oil, ashes, ground tobacco, saltwater, sugar solutions, washing powder/soap, and methylated spirits, which are very unsafe.

According to Varga, the commonly used methods of abortion among adolescents in South Africa are backstreet measures, which is attributable to women's inadequate knowledge of their legal status and eligibility for a safe abortion and a complex decision-making process. Another study on abortion among adolescents in developing countries states the same factors. Additional factors include gender inequality, an unmet need for contraceptive use, sexual education, high cost, and restrictive abortion laws.7,24 The issue of stigma is a serious issue, as highlighted by many other studies.- p.4

- Almost all ill health and mortality following unsafe abortion is preventable, and adolescents who are mostly in secondary schools are aware of illegal abortion practices and their consequences, which range from physical, psycho-social to economic in nature. The consequences are borne not only by women who acquire unsafe abortion but also by their families and the health care system. Both adolescents and non-adolescents suffer the consequences of abortion, but the impact is greater among adolescents.

Adolescents present with morbidities such as haemorrhage, severe anaemia, trauma, foreign body, sepsis, or mortality. These are frequently associated with the procedure used, for instance, women who use herbs to induce abortion are less likely to present with trauma, foreign body, or sepsis than are women who use surgical abortion, roots, or catheters. Similarly, women who use herbs are less likely to obtain blood transfusions than those who use any other method.

Haemorrhage is primarily the reason for admission among women who are having or have had an unsafe abortion. In a study by Ouattara et al, among 111 women who had an unsafe abortion, 75% suffered severe haemorrhage, 11% suffered endometritis, 5% suffered anaemia, and 5% suffered hepatonephritis, while six women died. Others may suffer from infection and infertility. Other effects are lifelong and devastating, such as psychosocial trauma, permanent disability, and infertility, a condition that upends their lives entirely.- p.5

- As many as 41 African countries have liberalized abortion laws, and three countries have legalized abortion entirely. Still much action is desired to ensure safe abortion and to address the impact of unsafe abortion. There is an urgent need for alternatives to abortion through expanded and enhanced family planning services, and if unintended pregnancy has already occurred for a woman who qualifies for safe legal abortion, then safety should be guaranteed. Additionally, the research agenda needs to be defined and advocacy strategies identified to curb the incidence of unsafe abortion (Table).

- p.5

- Most abortions follow unintended pregnancies, and adolescents are more vulnerable mainly due to socio-economic and cultural connotations, in addition to the harsh social stigma adolescents suffer in cases of premarital pregnancy. Therefore, societal norms, economic and legal obstacles have a profound influence on women's decision to have an abortion, especially unsafe abortion.6 The role of partners in influencing the decision to terminate pregnancy cannot be underrated in addition to whether he supplies funds for an abortion. When partners are supportive, women stand a better chance of retaining pregnancy, and if they should abort, the chance of having a safe abortion is significantly improved. Abortion practices differ by geographical region and range from traditional to modern methods, with rural teenagers more involved in the use of the former than urban-dwelling teenagers. However, modern methods are self-prescribed and are procured over the counter. Herbs and roots are commonly used to induce abortion in 42% of rural and 54% of urban women.30 Nonetheless, the use of roots is more associated with complications than herbs.

- p.5

- Unsafe backstreet methods include clandestine, self-prescribed pharmaceuticals, battery acid, crushed bottles, pain medication, sedatives, anaesthesia, antibiotics, chlorine, white Quinine, roots (cassava- cyanide), aloevera, castor oil, ashes, ground tobacco, salt water & sugar solutions, parsley oil, laxative, brandy, hot pepper salt, physical removal (with cassava root), chilli, or pawpaw, physical charms, boiled beer, tea, fanta, coca cola, washing powder/soap, and methylated spirit, physical exercises, inserting objects in the vagina, receiving a heavy massage, receiving an injection, taking oxytocin, inserting a catheter, taking a tablet, taking home remedies, an herbal concoction, or an herbal enema.

Safe methods include dilation and curettage (D&C), manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), and taking Cytotec.- Table 1, p.6

- Following unsafe abortion, 68 000 women die each year globally, while 5.3 million suffer disabilities that may be temporary or permanent6 and that are more common among women beyond 12 weeks of gestation. The public health burden of abortion remains the highest in developing countries with restrictive laws on abortion that compel women to resort to unsafe abortion, leading to injuries and, in some instances, maternal mortality.

The consequences are not only faced by women and their families but also by service providers. Physicians in countries where abortion is restricted may be surrounded by compromising terms and eventually suffer formidable penalties.- p.6

- Control strategies to abortion should strive to prevent unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and related complications. By all means, unintended pregnancies must be prevented, and if they occur, measures should be taken to prevent victims from procuring an unsafe abortion.

These goals can be achieved by providing sexuality education, increasing access to contraception, meeting the family planning needs of individuals, offering and increasing access to safe legal induced abortion, and providing timely care for complications. These actions should be taken across various age groups, although special focus should be afforded to those below 25 years of age, given their greater vulnerability. There is also a need to create awareness of the risks associated with unplanned pregnancies and induced abortions mostly by unskilled providers. Understanding the factors behind the persistence of unsafe abortion mostly in developing countries and finding sustainable solutions are equally vital. Women willing to share their stories concerning unwanted or unplanned pregnancies and abortion should be given forums and be protected to facilitate their emotional healing and to enable others to learn from their stories.- pp.6-7

- Although adolescents and non-adolescents alike suffer similar abortion complications, adolescent-specific reproductive health policies, and particularly their implementation, are critically desired. Targets should be both in-school and out-of-school adolescents. Additionally, policies concerning the respect and protection of women and other vulnerable groups need to be implemented. Adolescents themselves report the need for adequate information concerning reproductive health issues because in most cases, they are provided with information that is too superficial to help them when confronted with sexual and reproductive health challenges. For example, they have information regarding condom use29 but do not know how to use them correctly and consistently. Adolescents and young adults need varying levels of protection and safety to aid them in making autonomous decisions and to be able to learn and grow. In the case of pregnancy, they need sufficient information, counselling, parental involvement, and contraceptive options.

Additionally, identifying key areas of research and advocacy are equally important to control strategies.- p.7

- In conclusion, adolescents are mostly likely to use clandestine methods of abortion, the consequences of which are devastating, lifelong, or even fatal. Awareness and the effective utilization of adolescent- and youth-friendly services would minimize the problem. Social and emotional support in the event of unintended pregnancy is necessary. Awareness of who qualifies for a legal safe abortion and where it can be accessed is still low; hence, it should be included in health education if positive adolescent health outcomes should be realized.

- p.7

"Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice" (2000)

[edit]Berer M (2000). "Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (5): 580–592. PMC 2560758. PMID 10859852.