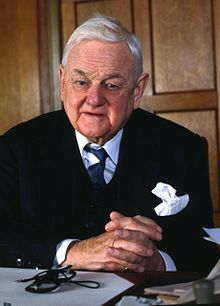

Quintin Hogg, Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone

Appearance

The Right Honourable Quintin McGarel Hogg, Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone KG CH PC (9 October 1907 – 12 October 2001), formerly 2nd Viscount Hailsham (1950–1963), was a British Conservative politician.

Quotes

[edit]1930s

[edit]- Our duty is to make our country so strong that no aggressor will challenge us.

- Speech (13 October 1938), quoted in Quintin Hogg, The Left was Never Right (1945), p. 200, n. 1

- The British people must be strong. If we talk we must be ready to act. We must speak with the authority of the strong because our voice is practically the only voice in the world which will speak out with authority for right.

- Speech (14 October 1938), quoted in Quintin Hogg, The Left was Never Right (1945), p. 200, n. 1

- I believe that the proper way to approach this problem is not to wait until Herr Hitler makes more demands, but tell him we are going to make some demands. I should tell him that if he wanted anything he must first come into the society of nations and play his part.

- Speech (27 October 1938), quoted in Quintin Hogg, The Left was Never Right (1945), p. 200, n. 1

- I have never believed in peace at any price.

- Speech (4 February 1939), quoted in Quintin Hogg, The Left was Never Right (1945), p. 200, n. 1

1940s

[edit]- Conservatives do not believe that political struggle is the most important thing in life... The simplest among them prefer fox-hunting—the wisest religion.

- The Case for Conservatism (1947), p. 10

- Being Conservative is only another way of being British.

- The Case for Conservatism (1947)

The Left was Never Right (1945)

[edit]- On the debate on the occupation of the Ruhr (Hansard, 13th–15th February 1923) the whole Left attacked France as "militaristic", "obsessed by fears which are largely the result of its own reactionary policy", "immoral", and aimed "at the complete destruction of Germany". The diehards did not take the same view. Lt.-Col. Croft (Bournemouth) (now Lord Croft): "I think Germany has shown pretty clearly that she is not going to do more than she can [help]. She is going to try and convince us that she cannot do anything like as much as we ask." Sir F. Banbury (whose pride was that he had only once voted for an Act of Parliament in his life): "I believe that if the Germans were given time to recover they would use that time in order again to commence a European war." Mr. Remer: "Our past policy has encouraged Germany to make defaults."

I mention these views, not because they are my own; they are not. But they are a great deal nearer truth than the stuff the Left was talking at this time.- p. 35, n. 2

- It is simply not true, as the authors of Guilty Men and Cassius assert, that the Labour Party, as a Party, was not pacifist, that its pacifism was limited to a few groups or individuals, that its pacifism ceased on the appearance of Hitler or did not continue long after his rise to power. From the first the Labour Party was riddled with pacifism. Its theory was pacifist. Its leaders were pacifist. Its members were pacifist, and its declared policy was pacifist. Disarmament it preached as party policy and because Conservatives were known to preach patriotism and strong armaments. As early as 1922 pacifism became the official doctrine of the Labour movement. At the Edinburgh Conference in that year a motion was carried that Socialist Parties everywhere should "oppose any war entered into by any government, whatever the ostensible object of the war". In 1923 the Party Conference at London pronounced in favour of "immediate Universal Disarmament by mutual agreement". There are even now Labour Members of Parliament who would fail to understand that such a policy must always put a premium on aggression, since it would give a would-be aggressor an automatic start. In 1926 the Margate Conference approved a policy of treason by general strike, calling on the workers to "meet any threat of war so called defensive or offensive, by organizing a general resistance, including the refusal to bear arms, to produce armaments, or to render any material assistance". At the Birmingham Conference, 1928, the Party's policy: "Labour and the Nation" was adopted. This included the renunciation of War, and Disarmament.

- p. 46

- The truth which the Left would not face—and will not face, even now—is that from 1932 and probably from 1929 collective security was moribund, owing to the re-emergence of a Germany determined to destroy it, and the existence of a Japan which had never really believed in it. It could only rise from the dead by the development of a system of armaments in the hands of the peace-loving nations capable of defeating and destroying the governments in the aggressor countries. The only future of the League lay through rearmament, and not through opposition to it.

- p. 57

- The fact is that the 1935 election was fought very largely on the subject of armaments. The Government wanted to rearm "too little and too late", but still on a considerable—if not a "huge"—scale. The Socialists and Liberals condemned this policy as wrong, as false to "collective security", and as leading to a war that could otherwise be avoided... [T]his was the issue which the Labour Party chose to fight, late in 1935—the Government arms policy versus the Socialist policy of disarmament by agreement and an international air police force. Looking back on this issue in 1945, who can possibly doubt to-day that the Conservatives were right and that the Left was pitifully wrong?

- p. 59

- Some armaments for Great Britain are necessary on any view of collective security... "collective security", so far from being an excuse exonerating our country from possessing armaments, is in fact a commitment demanding a higher degree of preparation for war than the mere defence of its shores would entail. The Left never understood that their foreign policy was inconsistent with their defence policy, and so must be held responsible for our weakness. But responsibility does not end there. To carry on war (and this is what we should have had to do to vindicate "collective security") it is not enough to have arms. It is necessary to possess a higher degree of national unity than a single democratic party can afford. How on earth could we expect to defy Japan, or even miserable Italy, when for years—and even at the very time when it called for the use of "sanctions"—the Labour movement had been declaring that should sanctions lead to war, even a "so-called defensive" war, they should oppose its prosecution and call a general strike?

- p. 67

- The fundamental principle of all foreign policy is that enunciated by Mr. Walter Lippmann, when he writes that you must balance commitments with power. To fail to do this is not brave, moral, "realistic", "idealistic", "progressive", or "reactionary". It is merely silly. To incur commitments without building up power to discharge them and to call this practice collective security is at the worst political chicanery and at the best self-deception, and leads inevitably to bankruptcy, military, political, and moral. This was consistently the policy of the Left in the years 1919–39.

- p. 97

- The second principle is that a nation should know what its interests are and should then ascertain what military power is required to defend them. A nation which fails to do this does not thereby escape the necessity of fighting for its legitimate interests; it only ensures that when it does have to fight it will not have the power to fight successfully. The Left consistently denied this principle. The argument used amounted to the pretence that the protection by fair means of a legitimate interest was not a moral or righteous purpose in foreign policy. This delusion is based on the double fallacy of supposing that interests are always immoral things which it is wrong to defend and of supposing that interests which are not defended by those who possess them will ever be preserved by anyone else. To this day this fallacy permeates nearly all left-wing propaganda in domestic and foreign policy alike.

- pp. 97-98

- [W]e have always been determined to prevent a combination of forces hostile to ourselves and to separate such a combination when it has arisen; we have always resisted the domination of Europe by a single power, since such domination would cause us to live in a state of armed peace in order to prevent a sudden descent on our shores.

- p. 98

- The period immediately after the war came to an end with the French occupation of the Ruhr. Only Lord Rothermere ran a series of articles entitled "Hats off to France". The Left was furious. Even the moderate Right would not co-operate.

Yet if one thing is certain, it is clear that the occupation of the Ruhr was justified by the event. Germany had defaulted in her payments, claimed inability to pay. The French occupied the Ruhr, took over the coal mines, and worked them as a security for the debt. The Germans retaliated with their first inflation and with an attempt at a general strike. They tried to pretend that the inflation was involuntary. We now know better than that. When it was decided to reverse the policy Dr. Schacht put an end to the inflation in a matter of forty-eight hours. The general strike failed. The French occupied the Ruhr for a period of nine months. At the end of this time Germany capitulated, and the French had won. The six years succeeding this decisive event (1923–9) were the only peaceful years the Continent really knew between the wars. Whatever might be said by the friends of Germany the occupation of the Ruhr was a success.- p. 116

- To our refusal to accept the French view of German duplicity and to our failure to regard the peace treaties as binding, many of our present troubles are due.

- p. 117

- The Manchurian incident was the direct result of the London Conference negotiated by the Labour Government in 1930 under which the pacifist MacDonald and the almost wholly ignorant Henderson agreed to scrap five more battleships on behalf of Britain, induced American to scrap three, but failed to persuade the Japanese to scrap more than one. This agreement, which was hailed as a triumph for disarmament, was in reality the cause of the break-up of peace in the Far East, and the partial cause of our weakness against Italy in 1936. The responsibility for this lies with the Labour leaders and the party which supported them.

- p. 122

- The whole position is a crystal clear example of the proposition that commitments and power must be balanced. Failure to balance them leads to bankruptcy, moral, political, and diplomatic. Neither Britain nor America was capable of paying the debt of honour.

Why?

Not because we did not support the League. Not because we did not believe in collective security. Not because we loved the Japanese. The reason is much simpler. Years of pacifism, disarmament, and false economy had deprived us of the power to do so.- pp. 126-127

- [T]he Disarmament Conference met early in 1932. Under the Presidency of good Arthur Henderson, whose Naval Disarmament Conference in London had been such a success for the Japanese, the only fear in the heart of every good Leftist was, of course, that the wicked Tories with their insane love of armaments might sabotage the whole affair.

- p. 128

1960s

[edit]- A great party is not to be brought down because of a scandal by a woman of easy virtue and a proved liar.

- "Lord Hailsham speaks out", The Times (14 June 1963) p. 9

- On the Profumo affair. Interview with Robert McKenzie on Gallery for BBC Television.

- Lord Hailsham: But to try to turn it into a party issue, is really beyond belief contemptible.

Robert McKenzie: Do you feel that the others that have spoken out, the Bishops, The Times and so on, have tried to turn it into a party issue?

Hailsham: I think you have!- Conclusion of the same interview.

- If the British public falls for this, I think it would be stark, staring bonkers.

- "Tories to fight like fury, Party chairman says", The Times (13 October 1964) p. 12

- At a press conference on 12 October 1964 during the general election campaign, referring to the policies of the Labour Party.

- If you can tell me there are no adulterers on the front bench of the Labour Party you can talk to me about Profumo.

- Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay Smear (Fourth Estate, 1991) p. 48

- Reply to heckler's cry of "Profumo!" at a public meeting on 13 October 1964.

- Moderation is the hallmark of our country and the burden of our Conservative faith. ... [I]n an age of violence the Conservative watchwords must be law, justice, moderation and humanity.

- Speech to the Conservative Party Conference in Blackpool (10 October 1968), quoted in The Times (11 October 1968) p. 4

1970s

[edit]- There is a sense in which all law is nothing more nor less than a gigantic confidence trick.

- Speech to Devon Magistrates The Times (12 April 1972)

- Experience shows that at this rate of inflation, democracy cannot survive... A middle-class backlash is inevitable. A populist movement. In the end people will not put up with the law being broken and factions of the workers getting away with it with impunity. People will take control into their own hands, or a strong government will use the public forces to seize control. People will get hurt. Quite likely there will be a lot of violence one way or another. But in the end there is a limit to what middle-class people will tolerate.

- Remarks to Hugo Young (July 1974), quoted in Hugo Young, The Hugo Young Papers: Thirty Years of British Politics – Off the Record, ed. Ion Trewin (2008), p. 37

- It is an excellent thing that Mr Powell has joined the Ulster Unionists. They have found a new leader to desert, and he a fresh cause to betray.

- Remark (September 1974), quoted in Simon Heffer, Like the Roman: The Life of Enoch Powell (1998), p. 729

- It is not a point of which I am much ashamed. Having grown up in the 1930s, I have a hatred of unemployment. The reason why we over-reacted, if over-reacted we did, was because we hoped that, if it could be shown that we were doing our best to deal with avoidable unemployment, the unions would voluntarily restrain their demands and prevent suffering in the community. The truth is that Mr Powell is so intent for personal reasons on ruining Mr Heath that no attack, however violent, however irrational, or however evilly intentioned, is beyond him in his present frame of mind.

- Speech reported in The Daily Telegraph (9 October 1974), quoted in Simon Heffer, Like the Roman: The Life of Enoch Powell (1998), p. 736

- [The Labour Party's leadership is] dominated by rather rootless intellectuals or obviously bourgeois eccentrics like Mr Michael Foot and Mr Wedgwood Benn.

- Speech in Preston (8 October 1974), quoted in The Times (9 October 1974), p. 4

- What is urgently needed is some limitation on this nominally elected dictatorship. It is here that I join hands with the conventional Bill of Rights enthusiasts, of whom...I am not one.

- Letter to The Times (17 February 1976), p. 13

- We live under an elective dictatorship, absolute in theory if hitherto thought tolerable in practice. How far it is still tolerable is the question I want to raise.

- Richard Dimbleby Lecture ("Elective Dictatorship") (14 October 1976), quoted in The Times (15 October 1976), p. 4

- Nothing has shown so clearly the evils of elective dictatorship as the past few weeks, which had culminated in the Lib–Lab pact.

- Speech in Bexley, Sidcup (4 April 1977), quoted in The Times (5 April 1977), p. 2