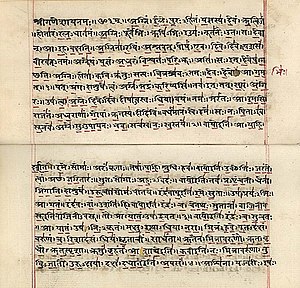

Rigveda

Appearance

The Rigveda (or Rig Veda) is a collection of over 1000 Vedic Sanskrit hymns to the Hindu gods. The oldest of the Hindu scriptures, which some have claimed date to to 7000–4000 BC, philological analysis indicates that it was probably composed in the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent, roughly between 1700–1100 BCE.

Quotes

[edit]Mandala 1

[edit]- The wise speak of what is One in many ways.

- Rig Veda 1.164.46

Mandala 2

[edit]- May we not anger you, O God, in our worship By praise that is unworthy or by scanty tribute.

- Rig Veda, II.33.4

Mandala 3

[edit]- Your ancient home, your auspicious friendship, O Heroes, your wealth is on the banks of the Jahnavi.

- Rigveda III.58.6. Jahnavi is another name for Ganges in Sanskrit literature and occurs also in Rigveda I.116.19, where it is associated with the Simsumara (I.116.18) [Gangetic river dolphin]. However, Griffith translated it as “the house of Jahnu”. As quoted from Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. Chapter 4.

Mandala 4

[edit]- Here did our human fathers take their places, fain to fulfil the sacred Law of worship.

- RV 4.1.13

Mandala 5

[edit]- Do adore with salutations the deva asura[Rudra].

- Rigveda V, 42, 11.

Mandala 6

[edit]- Brbu hath set himself above the Panis, o'er their highest head,

Like the wide bush on Ganga's bank.- Rigveda VI.45.31 (translated by R. Griffith)

Mandala 7

[edit]- Sarasvati, pure in her course from the mountains to the sea.

- RV VII.95.2

- Quoted in Frawley, David. The Rig Veda and the History of India. (2001). Quoted from Frawley, D. The Hindu, 25th June 2002. WITZEL’S VANISHING OCEAN – HOW TO READ VEDIC TEXTS ANY WAY YOU LIKE. A Reply to Michael Witzel’s article “A Maritime Rigveda? How not to read the Ancient Texts”.

Mandala 8

[edit]- We have drunk Soma and become immortal; we have attained the light, the Gods discovered. Now what may foeman's malice do to harm us? What, O Immortal, mortal man's deception?

- m. 8, hymn XLIIX

Mandala 9

[edit]- The people deck him like a docile king of elephants.

- Rg-Veda 9:57:3, thus translated by Ralph Griffith: The Hymns of the Rg-Veda, p.488., quoted in Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan invasion debate New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

Mandala 10

[edit]- Favour ye this my laud, O Gangā, Yamunā, O Sutudri, Paruṣṇī and Sarasvatī: With Asikni, Vitasta, O Marudvrdha, O Ārjīkīya with Susoma hear my call. First with Trstama thou art eager to flow forth, with Rasā, and Susartu, and with Svetya here, With Kubha; and with these, Sindhu and Mehatnu, thou seekest in thy course Krumu and Gomati.

- Variant: O Gangā, Yamunā, Sarasvatī, Shutudrī (Sutlej), Parushnī (Ravi), hear my praise! Hear my call, O Asiknī (Chenab), Marudvridhā (Maruvardhvan), Vitastā (Jhelum) with Ārjīkiyā and Sushomā. First you flow united with Trishtāmā, with Susartu and Rasā, and with Svetyā, O Sindhu (Indus) with Kubhā (Kabul) to Gomati (Gumal or Gomal), with Mehatnū to Krumu (Kurram), with whom you proceed together.

- Rigveda X.75.5-6

Quotes about the Rigveda

[edit]A

[edit]- Pischel and Geldner have done well to point out that these poems are not the productions of ignorant peasants, but of a highly cultured professional class, encouraged by the gifts of kings and the applause of courts (Einleitung p.xxiv). Just the same may be said of the Homeric bards and of those of Arthur‘s court [...]

- Historical Vedic Grammar. Arnold, E.V. 1897. In JAOS (Journal of the American Oriental Society), New Haven, Connecticut.

- It is impossible to read into the story of the Angirases, Indra and Sarama, the cave of the Panis and the conquest of the Dawn, the Sun and the Cows an account of a political and military struggle between Aryan invaders and Dravidian cave-dwellers. It is a struggle between the seekers of Light and the powers of Darkness; the cows are the illuminations of the Sun and the Dawn, they cannot be physical cows; the wide fear-free field of the Cows won by Indra for the Aryans is the wide world of Swar, the world of the solar Illumination, the threefold luminous regions of Heaven (Aurobindo [1914–20] 1998: 223)

- Sri Aurobindo, quoted in Danino, M. (2019). Demilitarizing the Rigveda: a scrutiny of Vedic horses, chariots and warfare., STUDIES IN HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Journal of the Inter-University Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences VOL. XXVI, NUMBER 1, SUMMER 2019

- We have in the Rig-veda,—the true and only Veda in the estimation of European scholars,—a body of sacrificial hymns couched in a very ancient language which presents a number of almost insoluble difficulties. ... The scholar in dealing with his text is obliged to substitute for interpretation a process almost of fabrication. We feel that he is not so much revealing the sense as hammering and forging rebellious material into some sort of shape and consistency.

- Sri Aurobindo The Secret of the Veda

- “the one considerable document that remains to us from the early period of human thought… when the spiritual and psychological knowledge of the race was concealed, for reasons now difficult to determine, in a veil of concrete and material figures and symbols which protected the sense from the profane and revealed it to the initiated. One of the leading principles of the mystics was the sacredness and secrecy of self-knowledge and the true knowledge of the Gods… Hence… (the mystics) clothed their language in words and images which had, equally, a spiritual sense for the elect, and a concrete sense for the mass of ordinary worshippers.”

- Sri Aurobindo. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- “The ritual system recognised by SAyaNa may, in its, externalities, stand; the naturalistic sense discovered by European scholarship may, in its general conception, be accepted; but behind them there is always the true and still hidden secret of the Veda - the secret words, niNyA vacAMsi, which were spoken for the purified in soul and the awakened in knowledge. To disengage this less obvious but more important sense by fixing the import of Vedic terms, the sense of Vedic symbols, and the psychological function of the Gods is thus a difficult but a necessary task.”

- Sri Aurobindo. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

B

[edit]- Max Muller's dating of the Veda illustrates the arbitrariness involved in the production of theories that are then propagated as "facts" in generations of schoolbooks. Muller, as I have noted, was fully aware of the arbitrary nature of his calculations (which, as Goldstucker pointed out, were based on a "ghost story" written in the twelfth century C.E.): "I ... have repeatedly dwelt on the hypothetical character of the dates" (1892, xiv). As Whitney noted, however: "We have already more than once seen it stated that 'Muller has ascertained the date of the Vedas to be 1200-1000 B.C.'" ([1874] 1987, 78). Winternitz also objected that "it became a habit . . . to say that Max Muller had proved 1200-1000 B.C. as the date of the Rg Veda. . . . Strange to say it has been quite forgotten on what a precarious footing [this opinion] stood" ([1907] 1962, 256).

- Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press.

E

[edit]- In the West, it is said that the whole tradition of philosophical thought is but a series of footnotes on the Greek philosopher Plato. Here, you could say that all Indian thought is but a series of footnotes on Dīrghatamas.

- About Dīrghatamas, an important Rigvedic poet well known for his philosophical verses in the RgVeda. Elst, Koenraad. Hindu dharma and the culture wars. (2019). New Delhi : Rupa.

G

[edit]- “On the whole ... the language of the first nine Mandalas must be regarded as homogeneous, inspite of traces of previous dialectal differences... With the tenth Mandala it is a different story. The language here has definitely changed.”

- B.K. Ghosh in The History and Culture of the Indian People, Vol. I: The Vedic Age edited by R.C. Majumdar, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Publications, Mumbai, 6th edition 1996. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Thus, the whole foundation of Mueller's date [for the Rigveda] rests on the authority of Somadeva, the author of "an Ocean of (or rather for) the River of Stories" who narrated his tales in the twelfth century after Christ. Somadeva, I am satisfied, would not be a little surprised to learn that 'a European point of view" raises a "ghost story" of his to the dignity of an historical document."

- Theodore Goldstucker, , quoted in Devahuti, D., & Indian History and Culture Society. (1980). Bias in Indian historiography. Delhi: D.K. Publications. p 48

- Goldstücker ([I860] 1965) objected that "neither is there a single reason to account for his allotting 200 years to the first of his periods, nor for his doubling this amount of time in the case of the Sutra period" (80). He points out that, ultimately, "the whole foundation of Muller's date rests on the authority of Somadeva . . . [who] narrated his tales in the twelfth century after Christ [and] would not be a little surprised to learn that 'a European point of view" raises a 'ghost story' of his to the dignity of an historical document" (91).

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 12

- “As in its original language, we see the roots and shoots of the languages of Greek and Latin, of Celt, Teuton and Slavonian, so the deities, the myths and the religious beliefs and practices of the Veda throw a flood of light upon the religions of all European countries before the introduction of Christianity. As the science of comparative philology could hardly have existed without the study of Sanskrit, so the comparative history of the religions of the world would have been impossible without the study of the Veda.”

- Ralph T.H. Griffith, in the preface to his translation. Hymns of the Rigveda (complete translation) by Ralph T.H. Griffith, 1889. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

H

[edit]- The Rigveda “reflects not so much a wandering life…. as a life stable and fixed, a life of halls and cities, and shows sacrificial cases in such detail as to lead one to suppose that the hymnists were not on the tramp, but were comfortable well-fed priests” [...] If the first home of the Aryans can be determined at all by the conditions topographical and meteorological, described in their early hymns, then decidedly the Punjab was not that home. For here there are neither mountains nor monsoon storms to burst, yet storm and mountain belong to the very marrow of the Rigveda. ...[it is] ―a district [...] where monsoon storms and mountain scenery are found, that district, namely, which lies South of Umballa (or Ambālā). It is here, in my opinion, that the Rigveda, taken as a whole, was composed. In every particular, this locality fulfils the physical conditions under which the composition of the hymns was possible, and what is of paramount importance, is the first district east of the Indus that does so.

- Edward Washburn Hopkins 1898. The Punjab and the Rig-Veda. pp. 19-28 in the ‘Journal of the American Oriental Society’, Vol. 19, July 1898

M

[edit]- [The Vedic Gods] “are nearer to the physical phenomena which they represent, than the gods of any other Indo-European mythology”.

- The Vedic Mythology by A.A Macdonell, Indological Book House, (reprint) Varanasi, 1963. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Max Müller, Weber, Muir, and others held that the Punjab was the main scene of the activity of the Rgveda, whereas the more recent view put forth by Hopkins and Keith is that it was composed in the country round the SarasvatI river south of modem AmbAla.”

- The History and Culture of the Indian People, Vol. I: The Vedic Age edited by R.C. Majumdar, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Publications, Mumbai, 6th edition 1996.

- "I need hardly say that I agree with almost every word of my critics. I have repeatedly dwelt on the entirely hypothetical character of the dates I ventured to assign to the first three periods of Vedic literature. All I have claimed for them has been that they are minimum dates"

- Max Muller. (Preface to the text of the Rigveda, Vol.4, p.xiii). Quoted in [1]

- "It is quite clear that we cannot fix a terminum a quo, whether the Vedic hymns were composed 1000 or 2000 or 3000 years BC, no power on earth will ever determine"

- Max Muller (Collected Works, Vol.II, p.91). Quoted in [2]

- The translation of the Veda will hereafter tell to a great extent on the fate of India and on the growth of millions of souls in that country. It is the root of their religion, and to show them what the root is, I feel sure, is the only way of uprooting all that has sprung from it during the last 3000 years.

- Max Muller writing about his translation of the Rigveda. Letter to his wife Georgina, Dec 1866, published in The Life and Letters of Right Honorable Friedrich Max Müller (1902) edited by Georgina Müller in Shourie, Arun (1994). Missionaries in India: Continuities, changes, dilemmas. New Delhi : Rupa & Co, 1994

P

[edit]- These dates Mueller later insisted were minimum dates only, , and latterly there has been a sort of tacit agreement.... to date the composition of the Rigveda somewhere about 1400-1500 BC, but without any absolutely conclusive evidence.

- Stuart Piggott. Prehistoric India. Quoted from B.B. Lal in : Indian History and Culture Society., Devahuti, D., & Indian History and Culture Society. (2012). Bias in Indian historiography. p.8

- That age [of the Rigveda] is not known with even an approximate degree of certainty.

- A.D. Pusalker , The History and Culture of the Indian People, Vol. I: The Vedic Age edited by R.C. Majumdar, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Publications, Mumbai, 6th edition 1996. quoted in S. Talageri, The Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism (1993)

S

[edit]- There was nothing in the Rgveda to look for a primitive or primarily nomadic society [sic]. . . . Chariots and wagons and boats which occur so frequently in the Rgveda do not agree well with nomadism. Movement of cars presupposes existence of roads and defined routes, which in turn presuppose settlements and regular traffic from point to point. Boats and ships are not floating logs. They presuppose ferry ghats and fixed destinations. . . , there was much in the Rgveda that defied explanation. . . . But instead of reconciling the discordant features, scholars either ignored them or distorted the facts and features. (Singh 1995, 8)

- Singh, Bhagavan. 1995. The Vedic Harappans. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 9

T

[edit]- If we can dig beneath the assumptions about meaning that overlay the text... we shall uncover a very different Rigveda from the one that we have come to accept.

- Thomson K. 2001 ‘The Meaning and Language of the Rigveda’ JIES vol 29 (295-349). (2001: 345). quoted from Kazanas, N. (2003). Final reply: Indo-Aryan migration debate. Journal of Indo-European studies, 31(1-2), 187-240.

- There is nothing in any of the 1,028 poems that make up the collection to suggest that their authors were incomers to the area that they describe in their poems. Rather the opposite.

- Karen Thomson, A Still Undeciphered Text: How the scientific approach to the Rigveda would open up Indo- European Studies,‘ p. 38.

V

[edit]- All attempts to date the Vedic literature on linguistic grounds have failed miserably for the simple reason that (a) the conclusions of comparative philology are often speculative and (b) no one has yet suceeded in showing how much change should take place in a language in a given period.

- K.C. Verma, MMR. quoted in S. Talageri, The Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism (1993)

W

[edit]- Of the Vedic poetic art Watkins writes: “The language of India from its earliest documentation in the Rigveda has raised the art of the phonetic figure to what many would consider its highest form”.

- Watkins. Nicholas Kazanas, "Indo-European Deities and the Rigveda," JIES 29 (2001), p. 257. quoting Watkins