The Communist Manifesto

Appearance

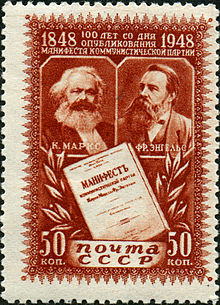

The Communist Manifesto (originally Manifesto of the Communist Party) is an 1848 political pamphlet by the German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London (in German as Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei) just as the Revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political documents. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and then-present) and the conflicts of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

Quotes

[edit](Full text online multiple formats)

Preamble

[edit]- A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism.

All the Powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to

exorcise this spectre: Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot,

French Radicals and German police-spies...

Section I Bourgeoisie and Proletariat

[edit]

- The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebeians, slaves; in the Middle Ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all of these classes, again, subordinate gradations.

The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones. Our epoch, the epoch of the bourgeoisie, possesses, however, this distinctive feature: it has simplified the class antagonisms. Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes, directly facing each other: Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.

- The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley of ties that bound man to his "natural superiors," and left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous "cash payment." Paragraph 14, lines 1-5.

- Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. Paragraph 18, lines 6-9.

- All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind. Paragraph 18, lines 12-14.

- A class of labourers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increase capital. These labourers, who must sell themselves piecemeal, are a commodity, like every other article of commerce, and are consequently exposed to all the vicissitudes of competition, to all the fluctuations of the market. Paragraph 30, lines 3-8.

- He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him. Hence, the cost of production of a workman is restricted, almost entirely, to the means of subsistence that he requires for his maintenance, and for the propagation of his race. Paragraph 31, lines 3-8.

- No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far, at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by the other portions of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker, etc. Paragraph 34.

- But every class struggle is a political struggle. Paragraph 39, lines 8-9.

- Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class. Paragraph 44, lines 1-2.

- Law, morality, religion, are to him so many bourgeois prejudices, behind which lurk in ambush just as many bourgeois interests. Paragraph 47, lines 7-9.

- What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable. Paragraph 53, lines 11-13.

Section II. Proletarians and Communists

[edit]

- Capital is a collective product, and only by the united action of many members, nay, in the last resort, only by the united action of all members of society, can it be set in motion. Paragraph 18

- All that we want to do away with is the miserable character of this appropriation, under which the labourer lives merely to increase capital, and allowed to live only so far as the interest to the ruling class requires it. Paragraph 20, lines 9-13.

- In bourgeois society, therefore, the past dominates the present; in Communist society, the present dominates the past. In bourgeois society capital is independent and has individuality, while the living person is dependent and has no individuality. Paragraph 22.

- You are horrified at our intending to do away with private property. But in your existing society, private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths. Paragraph 25.

- Communism deprives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriation. Paragraph 30.

- Just as, to the bourgeois, the disappearance of class property is the disappearance of production itself, so the disappearance of class culture is to him identical with the disappearance of all culture. That culture, the loss of which he laments, is, for the enormous majority, a mere training to act as a machine. Paragraph 34-35

- The working men have no country. We cannot take away from them what they have not got.

- Paragraph 51, lines 1-2.

- When people speak of ideas that revolutionize society, they do but express the fact that within the old society, the elements of a new one have been created, and that the dissolution of the old ideas keeps even pace with the dissolution of the old conditions of existence. Paragraph 58.

- The Communist revolution is the most radical rupture with traditional property relations; no wonder that its development involves the most radical rupture with traditional ideas. Paragraph 64.

- In place of the bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, shall we have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all. Paragraph 72 (last paragraph).

Section III. Socialist and Communist Literature

[edit]- In political practice, therefore, they join in all coercive measures against the working class; and in ordinary life, despite the high-falutin phrases, they stoop to pick up the golden apples, and to barter truth, love, and honour for traffic in wool, beet-root sugar, and potato spirits.

- Paragraph 9.

Section IV. Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties

[edit]

WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!

- The Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement. In France the Communists ally themselves with the Social-Democrats, against the conservative and radical bourgeoisie, reserving, however, the right to take up a critical position in regard to phrases and illusions traditionally handed down from the great Revolution.

- In short, the Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things.

- In all these movements they bring to the front, as the leading question in each, the property question, no matter what its degree of development at the time.

- Finally, they labour everywhere for the union and agreement of the democratic parties of all countries.

- The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

- Workers of the world, unite!

Quotes about

[edit]

- "With the clarity and brilliance of genius, this work outlines a new world-conception, consistent materialism, which also embraces the realm of social life; dialectics, as the most comprehensive and profound doctrine of development; the theory of the class struggle and of the world-historic revolutionary role of the proletariat—the creator of a new, communist society."

- Vladimir Lenin on the Manifesto, 1914,Marx/Engels Collected Works, Volume 6, p. xxvi.

- [W]hile there is no doubt that Marx at this time shared the usual townsman's contempt for, as well as ignorance of, the peasant milieu, the actual and analytically more interesting German phrase ("dem Idiotismus des Landlebens entrissen") referred not to "stupidity" but to "the narrow horizons", or "the isolation from the wider society" in which people in the countryside lived. It echoed the original meaning of the Greek term idiotes from which the current meaning of "idiot" or "idiocy" is derived, namely "a person concerned only with his own private affairs and not with those of the wider community". In the course of the decades since the 1840s, and in movements whose members, unlike Marx, were not classically educated, the original sense was lost and was misread.

- Eric Hobsbawm, 2011, p. 108.

- In fact, Marx and Engels were right when they observed in that other manifesto, the communist one of 1848, that free markets had in a short time created greater prosperity and more technological innovation than all previous generations combined and, with infinitely improved communications and accessible goods, free markets had torn down feudal structures and national narrow-mindedness. Marx and Engels realized much better than socialists today that the free market is a formidable progressive force. (Unfortunately, they were not sufficiently dialectically minded to understand that communism was a reactionary counterforce that would bring societies back to a kind of electrified feudalism.)

- Johan Norberg, The Capitalist Manifesto: Why the Global Free Market Will Save the World (2023), p. 2

External links

[edit]The Poverty of Philosophy, Karl Marx (1847)

- https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/61 Full text multiple formats

- Full text online at the Marxists Internet Archive