United States Constitution

Appearance

(Redirected from U.S. Constitution)

The United States Constitution is the supreme law of the United States of America. It was completed on 17 September 1787, with its adoption by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was later ratified by special conventions in each state. It created a federal union of states, and a federal government to operate that union.

Quotes

[edit]- We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

- The President, Vice-President, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

- Article II, sec. 4.

- Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on the confession in open court.

- Article III, sec. 3.

- This Constitution, and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be Supreme Law of the land; and the judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any thing in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary not with standing.

- Article VI, sec. 2.

The Bill of Rights (1791)

[edit]- Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

- First Amendment (1791).

- A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

- Second Amendment (1791).

- The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

- Fourth Amendment (1791).

- Nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

- Fifth Amendment (1791).

- In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

- Sixth Amendment (1791).

- In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

- Seventh Amendment (1791).

- Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted.

- Eighth Amendment (1791).

Further amendments

[edit]- Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

- Thirteenth Amendment (1865).

- All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall... abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

- Fourteenth Amendment, sec. 1 (1868).

- The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged... on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

- Fifteenth Amendment, sec. 1 (1870).

- The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be abridged... on account of sex.

- Nineteenth Amendment, sec. 1 (1920).

Quotes about the United States Constitution

[edit]Founding Fathers

[edit]- I confess that there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them. For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise.

- Benjamin Franklin, speech in the Constitutional Convention, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (September 17, 1787); reported in James Madison, Journal of the Federal Convention, ed. E. H. Scott (1893), p. 741.

- In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution, with all its faults, — if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of government but what may be a blessing to the people, if well administered; and I believe, farther, that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other.

- Benjamin Franklin, speech in the Constitutional Convention, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (September 17, 1787); reported in James Madison, Journal of the Federal Convention, ed. E. H. Scott (1893), p. 742.

- Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.

- Benjamin Franklin, letter to Jean-Baptiste Leroy (13 November 1789); reported in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 10th ed. (1919).

- Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human and suppose what they did to be beyond amendment. I knew that age well; I belonged to it and labored with it. It deserved well of its country. It was very like the present but without the experience of the present; and forty years of experience in government is worth a century of book-reading; and this they would say themselves were they to rise from the dead.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to H. Tompkinson (AKA Samuel Kercheval) (12 July 1816).

- I am certainly not an advocate for frequent and untried changes in laws and constitutions. I think moderate imperfections had better be borne with; because, when once known, we accommodate ourselves to them, and find practical means of correcting their ill effects. But I know also, that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed, and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times. We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to H. Tompkinson (AKA Samuel Kercheval) (12 July 1816).

- And lastly, let us provide in our constitution for its revision at stated periods.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to Samuel Kercheval (12 July 1816); reported in Paul L. Ford, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (1899), volume 10, p. 43.

- The constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to Judge Spencer Roane (September 6, 1819); reported in Andrew A. Lipscomb, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (1904) vol. 15, p. 213.

- In questions of power, then, let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.

- Thomas Jefferson, from the fair copy of the drafts of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798; reported in Paul L. Ford, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (1896), volume 7, p. 305.

- I sincerely rejoice at the acceptance of our new Constitution by nine States. It is a good canvas, on which some strokes only want retouching. What these are, I think are sufficiently manifested by the general voice from north to south, which calls for a bill of rights.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to James Madison (July 31, 1788); reported in Memoir, correspondence, and miscellanies from the papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volumes 1-2 (1829), p. 343.

- As the people are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power, is derived, it seems strictly consonant to the republican theory, to recur to the same original authority, not only whenever it may be necessary to enlarge, diminish, or new-model the powers of the government, but also whenever any one of the departments may commit encroachments on the chartered authorities of the others.

- Federalist No. 49 (February 2, 1788).

- Twenty years will produce all the mischief that can be apprehended from the liberty to import slaves. So long a term will be more dishonorable to the National character than to say nothing about it in the Constitution.

- James Madison, Madison Debates (25 August 1787).

- The danger of disturbing the public tranquillity by interesting too strongly the public passions, is a still more serious objection against a frequent reference of constitutional questions to the decision of the whole society.

- James Madison, Federalist No. 49 (February 2, 1788).

- My opinion is that a reservation of a right to withdraw... is a conditional ratification... Compacts must be reciprocal... The Constitution requires an adoption in toto, and for ever. It has been so adopted by the other States.

- James Madison, letter to Alexander Hamilton (20 July 1788).

- The government of the United States is a definite government, confined to specified objects. It is not like the state governments, whose powers are more general. Charity is no part of the legislative duty of the government.

- Whilst the last members were signing [the Constitution], Doctor Franklin, looking towards the President’s chair, at the back of which a rising sun happened to be painted, observed to a few members near him, that painters had found it difficult to distinguish in their art, a rising, from a setting, sun. I have, said he, often and often, in the course of the session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President, without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting; but now at length, I have the happiness to know, that it is a rising, and not a setting sun.

- James Madison, quoting Benjamin Franklin, Journal of the Federal Convention, ed. E. H. Scott (1893), p. 763.

- With respect to the words "general welfare," I have always regarded them as qualified by the detail of powers connected with them. To take them in a literal and unlimited sense would be a metamorphosis of the Constitution into a character which there is a host of proofs was not contemplated by its creators.

- James Madison, Letter to James Robertson (20 April 1831)

- Upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them citizens, and let them vote. Are they property? Why, then, is no other property included? The Houses in this city are worth more than all the wretched slaves which cover the rice swamps of South Carolina.

- The American constitutions were to liberty what a grammar is to language: they define its parts of speech, and practically construct them into syntax.

- Thomas Paine, The Rights of Man (1791), p. 44.

- Our chief danger arises from the democratic parts of our constitutions.

- Attributed to Virginia governor Edmund Randolph, by James McHenry in his notes of the Constitutional Convention (May 29, 1787); reported in Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, rev. ed. (1937), volume 1, p. 26.

- If in the opinion of the People, the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed.

- George Washington, farewell address (September 19, 1796); reported in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington (1940), volume 35, p. 229.

- It is too probable that no plan we propose will be adopted. Perhaps another dreadful conflict is to be sustained. If to please the people, we offer what we ourselves disapprove, how can we afterwards defend our work? Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair. The event is in the hand of God.

- George Washington, remarks at the first Continental Congress, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (May 14, 1787); reported in Max Farrand, The Framing of the Constitution of the United States (1934), p. 66.

- Should the States reject this excellent Constitution, the probability is, an opportunity will never again offer to cancel another in peace—the next will be drawn in blood.

- Attributed to George Washington in the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser (November 14, 1787), p. 3, column 1. Uncertainty in this attribution is reported in Charles Warren, The Making of the Constitution (1937, originally published 1928), p. 717, who quotes this, with slight variation in wording, but adds in a footnote: "As Madison does not mention this speech, there is some doubt as to the accuracy of the report".

Judicial interpretations

[edit]- To restate the key question in this case, the issue centrally debated by the parties: Absent congressional authorization, does the Elections Clause preclude the people of Arizona from creating a commission operating independently of the state legislature to establish congressional districts? The history and purpose of the Clause weigh heavily against such preclusion, as does the animating principle of our Constitution that the people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, 576 U.S. 787 (2015), at III Part C.

- As to the doctrine of slavery and the right of Christians to hold Africans in perpetual servitude, and sell and treat them as we do our horses and cattle, that, it is true, has been heretofore countenanced by the Province Laws formerly, but nowhere is it expressly enacted or established. It has been a usage–a usage which took its origin from the practice of some of the European nations, and the regulations of British government respecting the then-colonies, for the benefit of trade and wealth. But whatever sentiments have formerly prevailed in this particular or slid in upon us by the example of others, a different idea has taken place with the people of America, more favorable to the natural rights of mankind, and to that natural, innate desire of liberty, with which Heaven, without regard to color, complexion, or shape of noses-features, has inspired all the human race. And upon this ground our constitution of government, by which the people of this Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, sets out with declaring that all men are born free and equal, and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws, as well as life and property–and in short is totally repugnant to the idea of being born slaves. This being the case, I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.

- The Constitution was built for rough as well as smooth roads. In time of war the nation simply changes gears and takes the harder going under the same power.

- Harold Hitz Burton. Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304, 342 (1946).

- Time has proven the discernment of our ancestors, for even these provisions, expressed in such plain English words that it would seem the ingenuity of man could not evade them, are now, after the lapse of more than seventy years, sought to be avoided. Those great and good men foresaw that troublous times would arise when rulers and people would become restive under restraint, and seek by sharp and decisive measures to accomplish ends deemed just and proper, and that the principles of constitutional liberty would be in peril unless established by irrepealable law. The history of the world had taught them that what was done in the past might be attempted in the future. The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times and under all circumstances. No doctrine involving more pernicious consequences was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism, but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false, for the government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it which are necessary to preserve its existence, as has been happily proved by the result of the great effort to throw off its just authority.

- David Davis, Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 2, 120-21 (1866).

- The Constitution favors no racial group, no political or social group.

- William O. Douglas, Uphaus v. Wyman, 364 U.S. 388, 406 (1960), dissenting.

- This case involves a cancer in our body politic. It is a measure of the disease which afflicts us. Army surveillance, like Army regimentation, is at war with the principles of the First Amendment. Those who already walk submissively will say there is no cause for alarm. But submissiveness is not our heritage. The First Amendment was designed to allow rebellion to remain as our heritage. The Constitution was designed to keep government off the backs of the people. The Bill of Rights was added to keep the precincts of belief and expression, of the press, of political and social activities free from surveillance. The Bill of Rights was designed to keep agents of government and official eavesdroppers away from assemblies of people. The aim was to allow men to be free and independent and to assert their rights against government. There can be no influence more paralyzing of that objective than Army surveillance. When an intelligence officer looks over every nonconformist's shoulder in the library, or walks invisibly by his side in a picket line, or infiltrates his club, the America once extolled as the voice of liberty heard around the world no longer is cast in the image which Jefferson and Madison designed, but more in the Russian image.

- Justice William O. Douglas, Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1 (1972), dissenting.

- The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows.

- Stephen J. Field, Cummings v. State of Missouri, 71 U. S. 277, 325 (1866).

- The ultimate touchstone of constitutionality is the Constitution itself and not what we have said about it.

- Felix Frankfurter, concurring in Graves v. New York ex rel. O'Keefe, 306 U.S. 446 (1939).

- Is that which was deemed to be of so fundamental a nature as to be written into the Constitution to endure for all times to be the sport of shifting winds of doctrine?

- Felix Frankfurter, dissenting in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett, 319 U.S. 624, 642 (1943).

- It is fundamental that the great powers of Congress to conduct war and to regulate the Nation's foreign relations are subject to the constitutional requirements of due process. The imperative necessity for safeguarding these rights to procedural due process under the gravest of emergencies has existed throughout our constitutional history, for it is then, under the pressing exigencies of crisis, that there is the greatest temptation to dispense with fundamental constitutional guarantees which, it is feared, will inhibit governmental action. "The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times, and under all circumstances." Ex parte Milligan, 4 Wall. 2, 71 U. S. 120-121. The rights guaranteed by the Fifth and Sixth Amendments are "preserved to every one accused of crime who is not attached to the army, or navy, or militia in actual service." Id. at 71 U. S. 123. "[I]f society is disturbed by civil commotion -- if the passions of men are aroused and the restraints of law weakened, if not disregarded -- these safeguards need, and should receive, the watchful care of those intrusted with the guardianship of the Constitution and laws. In no other way can we transmit to posterity unimpaired the blessings of liberty, consecrated by the sacrifices of the Revolution." Id. at 71 U. S. 124.

- Arthur Joseph Goldberg, Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144 (1963), at 164-165.

- In view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.

- John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 559 (1896).

- The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare, nor should this Court, ordained as a judicial body, be thought of as a general haven for reform movements.

- John Marshall Harlan II, Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 624–25 (1964) (dissenting).

- That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616; 630 (1919) (dissenting).

- The interpretation of constitutional principles must not be too literal. We must remember that the machinery of government would not work if it were not allowed a little play in its joints.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 U.S. 499, 501 (1931).

- Our protection against all kinds of fanatics and extremists, none of whom can be trusted with unlimited power over others, lies not in their forbearance but in the limitations of our Constitution.

- Robert H. Jackson, American Communications Association v. Douds, 339 U.S. 382, 439 (1950).

- The laws and Constitution are designed to survive, and remain in force, in extraordinary times. Liberty and security can be reconciled; and in our system they are reconciled within the framework of the law.

- Anthony Kennedy, Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008) (opinion of the court).

- The people made the Constitution, and the people can unmake it. It is the creature of their own will, and lives only by their will.

- John Marshall, Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheaton (19 U.S.) 264, 389 (1821).

- We must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding.

- John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 407 (1819).

- Individuals who have been wronged by unlawful racial discrimination should be made whole; but under our Constitution there can be no such thing as either a creditor or a debtor race. That concept is alien to the Constitution's focus upon the individual. ...To pursue the concept of racial entitlement - even for the most admirable and benign of purposes - is to reinforce and preserve for future mischief the way of thinking that produced race slavery, race privilege and race hatred. In the eyes of government, we are just one race here. It is American.

- Antonin Scalia, Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Mineta, 534 U.S. 103 (1995).

- All general business corporation statues appear to date from well after 1800... The Framers (of the Constitution) thus took it as a given that corporations could be comprehensively regulated in the service of the public welfare. Unlike our colleagues, they had little trouble distinguishing corporations from human beings, and when they constitutionalized the right to free speech in the First Amendment, it was the free speech of individual Americans they had in mind.

The fact that corporations are different from human beings might seem to need no elaboration, except that the majority opinion almost completely elides it…. Unlike natural persons, corporations have ‘limited liability’ for their owners and managers, ‘perpetual life,’ separation of ownership and control, ‘and favorable treatment of the accumulation of assets….’ Unlike voters in U.S. elections, corporations may be foreign controlled.

...It might be added that corporations have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires. Corporations help structure and facilitate the activities of human beings, to be sure, and their ‘personhood’ often serves as a useful legal fiction. But they are not themselves members of ‘We the People’ by whom and for whom our Constitution was established. - (TH: In Justice Stevens’ dissent in Citizens United, he pointed out that corporations in their modern form didn’t even exist when the Constitution was written in 1787 and got its first ten amendments in 1791, including the First which protects free speech)

- Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, quoted by Thom Hartmann in Krysten Sinema is the Epitome of Political Corruption, Thom Hartmann, CounterPunch, October 14, 2021

- In addition to this immediate drowning out of noncorporate voices, there may be deleterious effects that follow soon thereafter. Corporate ‘domination’ of electioneering can generate the impression that corporations dominate our democracy. When citizens turn on their televisions and radios before an election and hear only corporate electioneering, they may lose faith in their capacity, as citizens, to influence public policy. A Government captured by corporate interests, they may come to believe, will be neither responsive to their needs nor willing to give their views a fair hearing. The predictable result is cynicism and disenchantment: an increased perception that large spenders ‘call the tune’ and a reduced ‘willingness of voters to take part in democratic governance.’ To the extent that corporations are allowed to exert undue influence in electoral races, the speech of the eventual winners of those races may also be chilled.

Politicians who fear that a certain corporation can make or break their reelection chances may be cowed into silence about that corporation.

On a variety of levels, unregulated corporate electioneering might diminish the ability of citizens to ‘hold officials accountable to the people,’ and disserve the goal of a public debate that is ‘uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.’- Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, quoted by Thom Hartmann in Krysten Sinema is the Epitome of Political Corruption, Thom Hartmann, CounterPunch, October 14, 2021

- If the provisions of the Constitition be not upheld when they pinch as well as when they comfort, they may as well be abandoned.

- George Sutherland, Home Building & Loan Association v. Blaisdell, 290 U.S. 398, 483 (1934).

- One country, one constitution, one destiny.

- Daniel Webster, Speech (15 March 1837); reported in Edward Everett, ed., The Works of Daniel Webster (1851), page 349

Others

[edit]- The tank, the B-52, the fighter-bomber, the state-controlled police and military are the weapons of dictatorship. The rifle is the weapon of democracy. Not for nothing was the revolver called an "equalizer." Egalite implies liberte. And always will. Let us hope our weapons are never needed — but do not forget what the common people of this nation knew when they demanded the Bill of Rights: An armed citizenry is the first defense, the best defense, and the final defense against tyranny.

- Edward Abbey, as quoted in Abbey's Road (1979)

- The Constitution of the United States did not create a democracy by modern standards. Who could vote in elections was left up to the individual states to determine. While northern states quickly conceded the vote to all white men irrespective of how much income they earned or property they owned, southern states did so only gradually. No state enfranchised women or slaves, and as property and wealth restrictions were lifted on white men, racial franchises explicitly disenfranchising black men were introduced. Slavery, of course, was deemed constitutional when the Constitution of the United States was written in Philadelphia, and the most sordid negotiation concerned the division of the seats in the House of Representatives among the states. These were to be allocated on the basis of a state’s population, but the congressional representatives of southern states then demanded that the slaves be counted. Northerners objected. The compromise was that in apportioning seats to the House of Representatives, a slave would count as three-fifths of a free person. The conflicts between the North and South of the United States were repressed during the constitutional process as the three-fifths rule and other compromises were worked out. New fixes were added over time—for example, the Missouri Compromise, an arrangement where one proslavery and one antislavery state were always added to the union together, to keep the balance in the Senate between those for and those against slavery. These fudges kept the political institutions of the United States working peacefully until the Civil War finally resolved the conflicts in favor of the North.

- Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012), p. 42

- The laws and constitution of our government ought to be regarded with reverence. Man must have an idol. And our political idol ought to be our constitution and laws. These, like the ark of the covenant among the Jews, ought to be sacred from all profane touch. If we would preserve our government uncorrupted, and promote our own peace and happiness, we must reverence the laws, and every lawful act and ordinance of our administration. If we will have a rational government on the basis of liberty and equality, the people must themselves be rational, enlightened, wise, and virtuous; they must be modest, and willing to learn from true sources; they must be respectful of understanding, wisdom, and experience; and they must cease to listen to ignorance, folly, and flattery.

- Alexander Addison, Charges to Grand Juries of the Counties of the Fifth Circuit, in the State of Pennsylvania (1800), p. 242

- Think back to 1787. Who were 'we the people'? … They certainly weren't women … they surely weren't people held in human bondage. The genius of our Constitution is that over now more than 200 sometimes turbulent years that 'we' has expanded and expanded.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the fight for equality. Source: Appearance at Georgetown University, 2015. As quoted in: Li Cohen (September 19, 2022): Ruth Bader Ginsburg's iconic quotes on law, love and the fight for equality. In: CBS News. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022.

- I never thought carefully before about the clause of the constitution that counted slaves as three-fifths of a man for purposes of apportionment. Had they been counted as whole persons, it would've increased the south's power in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. Thus, rather than being a provision that disparaged black people, it actually was an effort to diminish the power of their oppressors.

- If this statement by Judge Cooley is true, and the authority for it is unimpeachable, then the theory that the Constitution is a written document is a legal fiction. The idea that it can be understood by a study of its language and the history of its past development is equally mythical. It is what the Government and the people who count in public affairs recognize and respect as such, what they think it is. More than this. It is not merely what it has been, or what it is today. It is always becoming something else and those who criticize it and the acts done under it, as well as those who praise, help to make it what it will be tomorrow.

- Charles A. Beard and William Beard, The American Leviathan: The Republic in the Machine Age (1931), p. 39

- The Constitution is to anchor us in principles that help temper the mood of the country.

- Glenn Beck, interview on New Day (January 2016), CNN

- The layman's Constitutional view is that what he likes is Constitutional and that which he doesn't like is un-Constitutional. That about measures up the Constitutional acumen of the average person.

- Hugo Black, news conference, Washington, D.C., reported in The New York Times (February 25, 1971), p. 38

- We have seen that the American Constitution has changed, is changing, and by the law of its existence must continue to change, in its substance and practical working even when its words remain the same.

- James Bryce, The American Commonwealth, new ed. (1924), volume 1, chapter 35, p. 401

- The great generalities of the constitution have a content and a significance that vary from age to age.

- Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process (1921), p. 17.

- Today, we understand the United States Constitution as the “supreme law of the land” as ratified through official public procedures. But in the 18th century, the term constitution more commonly referred to a whole way of life, as in the “ancient constitution” sometimes described as the unwritten source of English law. Tribal constitutions were described in similar terms; having a sachem who sold out the tribe was unconstitutional in the sense of being incompatible with the Mohegan way of life. Native constitutions were culturally embedded to a degree that the U.S. Constitution, which was purpose-built to govern a society of factions “actuated by different sentiments and views,” wasn’t.

Historians are finally beginning to confront the hard fact that the U.S. Constitution rules over Native nations as a kind of imperial law. This is ironic, given the “anti-colonial” ambitions of the U.S. rebels against British rule.- Ryan O. Carr, “A Native American Declaration of Independence”, The Atlantic, (July 4th 2024)

- One thing has struck me as very strange, and that is the resurgence of the one-man power after all these centuries of experience and progress. It is curious how the English-speaking peoples have always had this horror of one-man power. They are quite ready to follow a leader for a time, as long as he is serviceable to them; but the idea of handing themselves over, lock, stock and barrel, body and soul, to one man, and worshiping him as if he were an idol? That has always been odious to the whole theme and nature of our civilization. The architects of the American Constitution were as careful as those who shaped the British Constitution to guard against the whole life and fortunes, and all the laws and freedom of the nation, being placed in the hands of a tyrant. Checks and counter-checks in the body politic, large devolutions of State government, instruments and processes of free debate, frequent recurrence to first principles, the right of opposition to the most powerful governments, and above all ceaseless vigilance, have preserved, and will preserve, the broad characteristics of British and American institutions. But in Germany, on a mountain peak, there sits one man who in a single day can release the world from the fear which now oppresses it; or in a single day can plunge all that we have and are into a volcano of smoke and flame.

- Winston Churchill, A Hush Over Europe, 8 August 1939

- Most faults are not in our Constitution, but in ourselves.

- Ramsey Clark, remarks at meeting sponsored by the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, New York City, 11 November 1970, to debate the merits of a new constitution drafted by Rexford Tugwell, as reported by The Washington Post (12 November 1970), p. A2.

- The Constitution was not made merely for the generation that then existed, but for posterity — unlimited, undefined, endless, perpetual posterity.

- Henry Clay, speech before the U.S. Senate (1850); reported in The American Whig Review (1850), volume 11, page 229.

- To live under the American Constitution is the greatest political privilege that was ever accorded to the human race.

- Calvin Coolidge, Message to the National Security League in honor of Constitution Day, quoted in New York Times (17 September 1923) "Ceremonies Mark Constitution Day", at the White House, 12 December 1924. Reported as unverified in Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations (1989).

- Numbered among our population are some 12,000,000 colored people. Under our Constitution their rights are just as sacred as those of any other citizen. It is both a public and a private duty to protect those rights.

- Calvin Coolidge, State of the Union Address (6 December 1923).

- The Constitution is the sole source and guaranty of national freedom.

- Calvin Coolidge, address accepting nomination as Republican candidate for president, Washington, D.C. (August 4, 1924); published as Address of Acceptance (1924), p. 15. Address accepting nomination as Republican candidate for president, Washington, D.C. (4 August 1924); published as Address of Acceptance (1924), p. 15.

- Our Constitution guarantees equal rights to all our citizens, without discrimination on account of race or color. I have taken my oath to support that Constitution. It is the source of your rights and my rights. I propose to regard it, and administer it, as the source of the rights of all the people, whatever their belief or race.

- Calvin Coolidge, letter to Charles F. Gardner (9 August 1924), Fort Hamilton, New York, as quoted in "IX: Equality of Rights", Foundations of the Republic (1926), p. 71-72.

- If the Constitution of the United States be tyranny; if the rule that no one shall be convicted of a crime save by a jury of his peers; that no orders of nobility shall be granted; that slavery shall not be permitted to exist in any state or territory; that no one shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law; if these and many other provisions made by the people be tyranny, then the Supreme Court when it makes decisions in accordance with these principles of our fundamental law is tyrannical. Otherwise it is exercising the power of government for the preservation of liberty. The fact is that the Constitution is the source of our freedom. Maintaining it, interpreting it, and declaring it, are the only methods by which the Constitution can be preserved and our liberties guaranteed.

- Calvin Coolidge, Ordered Liberty and World Peace (6 September 1924), address delivered at the dedication of a monument to Lafayette, Saturday, Baltimore, Maryland.

- It is a time for truth. It is a time for liberty. It is a time to reclaim the Constitution of the United States.

- Ted Cruz, presidential declaration speech, Ted Cruz declaration speech: Full transcript, as quoted in Independant.co.uk (23 March 2015).

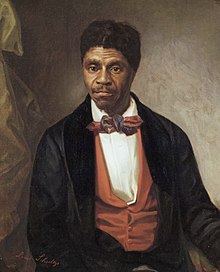

- The Constitution of the United States, in its essential spirit and intention, recognizes the essential manhood of Dred Scott as absolutely as it does that of the President, of the Chief Justice, or of any Senator of the United States... The Democratic Party then, as now, was in open alliance with slavery, in a conspiracy against the Constitution and the peace of the country.

- George William Curtis, as quoted in "The Present Aspect of the Slavery Question" (18 October 1859), New York City.

- The Constitution is a delusion and a snare if the weakest and humblest man in the land cannot be defended in his right to speak and his right to think as much as the strongest in the land.

- Clarence Darrow Address to the court in People v. Lloyd (1920)

- The Constitution itself. Its language is 'we the people'. Not we the white people, not even we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low, but we the people. Not we the horses, sheep, and swine, and wheel-barrows, but we the people, we the human inhabitants. If Negroes are people, they are included in the benefits for which the Constitution of America was ordained and established. But how dare any man who pretends to be a friend to the Negro thus gratuitously concede away what the Negro has a right to claim under the Constitution?

- Frederick Douglass, "The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?" (26 March 1860), Glasgow, United Kingdom

- The Constitution will afford slavery no protection when it shall cease to be administered by slaveholders. They see, moreover, that if there is once a will in the people of America to abolish slavery, this is no word, no syllable in the Constitution to forbid that result. They see that the Constitution has not saved slavery in Rhode Island, in Connecticut, in New York, or Pennsylvania; that the Free States have only added three to their original number. There were twelve Slave States at the beginning of the Government: there are fifteen now.

- Frederick Douglass, "The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?" (26 March 1860), Glasgow, United Kingdom

- It has often been suggested to me that the Constitution of the United States is a sufficient safeguard for the freedom of its citizens. It is obvious that even the freedom it pretends to guarantee is very limited. I have not been impressed with the adequacy of the safeguard. The nations of the world, with centuries of international law behind them, have never hesitated to engage in mass destruction when solemnly pledged to keep the peace; and the legal documents in America have not prevented the United States from doing the same. Those in authority have and always will abuse their power. And the instances when they do not do so are as rare as roses growing on icebergs. Far from the Constitution playing any liberating part in the lives of the American people, it has robbed them of the capacity to rely on their own resources or do their own thinking. Americans are so easily hoodwinked by the sanctity of law and authority. In fact, the pattern of life has become standardized, routinized, and mechanized like canned food and Sunday sermons.

- [T]he Constitution deliberately avoided the direct use of the word 'slavery' because, as James Madison explained, the Framers did not want to give express approval to the idea that there could be 'property in man'.

- Ethan Greenberg, Dred Scott and the Dangers of a Political Court, p. 12

- Many of our constitutional rights as Americans have been revoked by judicial fiat, including the right to privacy. Corporate money floods political campaigns in the name of "free speech." The United States is a failed democracy and a mafia state, the natural result of what happens when capitalism is deregulated.

- I always defended the Constitution, because it was for liberty. It was ordained by the people of the United States. Not by a superannuated old mummy of a judge, and a Jesuit at that, but by the people of the United States. To establish justice, secure the blessing of liberty for themselves and their posterity, and to secure the natural rights of every human being within its exclusive jurisdiction. Therefore, I love it. These men can perceive nothing in the Constitution but slavery.

- Owen Lovejoy, speech to the United States House of Representatives (5 April 1860)

- I love the Constitution. It is enshrined in my heart. I love it better than any dozen Democrats in the land do tonight.

- Owen Lovejoy, speech (October 1860)

- When this nation was in trouble, in its early struggles, it looked upon the Negro as a citizen. In 1776 he was a citizen. At the time of the formation of the Constitution the Negro had the right to vote in eleven States out of the old thirteen. In your trouble you have made us citizens. In 1812 General Jackson addressed us as citizens; 'fellow-citizens'. He wanted us to fight. We were citizens then! And now, when you come to frame a conscription bill, the Negro is a citizen again. He has been a citizen just three times in the history of this government, and it has always been in time of trouble. In time of trouble we are citizens. Shall we be citizens in war, and aliens in peace? Would that be just?

- Frederick Douglass, "What the Black Man Wants", speech in Boston, Massachusetts (1865)

- [T]he Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color.

- Frederick Douglas, "Reconstruction", from Atlantic Monthly 18 (1866): pp. 761-765

- The Constitution was born in compromise and survived a civil war when compromise broke down only by radically changing itself. It had relied on the Great Compromise between the small and big states and on a second, “rotten” compromise between the free North and the slaveholding South. In return for empowering the federal government over trade and commerce, the future of slavery was left aside, although slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of apportioning representation. Legally, the “rotten” compromise between North and South was abandoned with the abolition of slavery and the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, a constitutional passkey for establishing personal and corporate rights in federal and, increasingly, in state law. The passkey became a liberal tool, used first by right-wing liberals to enfranchise business from the claims of labor and later by left-wing liberals to free citizens from the moral interferences of law on their private conduct.

- Edmund Fawcett, Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition (2020), p. 36

- The words of the Constitution ... are so unrestricted by their intrinsic meaning or by their history or by tradition or by prior decisions that they leave the individual Justice free, if indeed they do not compel him, to gather meaning not from reading the Constitution but from reading life.

- Felix Frankfurter, The Supreme Court, vol. 3, no. 1, Parliamentary Affairs (London, Winter 1949).

- During the war of the Revolution, and in 1788, the date of the adoption of our national Constitution, there was but one State among the thirteen whose constitution refused the right of suffrage to the negro. That State was South Carolina. Some, it is true, established a property qualification; all made freedom a prerequisite; but none save South Carolina made color a condition of suffrage. The Federal Constitution makes no such distinction, nor did the Articles of Confederation. In the Congress of the Confederation, on the 25th of June, 1778, the fourth article was under discussion. It provided that 'the free inhabitants of each of these States — paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted — shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States.' The delegates from South Carolina moved to insert between the words 'free inhabitants' the word 'white', thus denying the privileges and immunities of citizenship to the colored man. According to the rules of the convention, each State had but one vote. Eleven States voted on the question. One was divided; two voted aye; and eight voted no. It was thus early, and almost unanimously, decided that freedom, not color, should be the test of citizenship. No federal legislation prior to 1812 placed any restriction on the right of suffrage in consequence of the color of the citizen. From 1789 to 1812 Congress passed ten separate laws establishing new Territories. In all these, freedom, and not color, was the basis of suffrage.

- James A. Garfield, Oration delivered at Ravenna, Ohio (4 July 1865).

- The will of the nation, speaking with the voice of battle and through the amended Constitution, has fulfilled the great promise of 1776 by proclaiming 'liberty throughout the land to all the inhabitants thereof.' The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787. NO thoughtful man can fail to appreciate its beneficent effect upon our institutions and people. It has freed us from the perpetual danger of war and dissolution. It has added immensely to the moral and industrial forces of our people. It has liberated the master as well as the slave from a relation which wronged and enfeebled both. It has surrendered to their own guardianship the manhood of more than 5,000,000 people, and has opened to each one of them a career of freedom and usefulness.

- James A. Garfield, Inaugural address (March 4, 1881).

- As the British Constitution is the most subtile organism which has proceeded from the womb and the long gestation of progressive history, so the American Constitution is, so far as I can see, the most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.

- William Gladstone, "Kin Beyond Sea", The North American Review (September–October 1878), p. 185.

- [U]nder the Constitution in its most liberal interpretation, and admitting our cherished American doctrine of equal human rights, if a white man pleases to marry a black woman, the mere fact that she is black gives no one a right to interfere to prevent or set aside such marriage.

- We believe, and I think properly, that when the men who met in 1787 to make our Constitution they made the best political document ever made; but, remember, they did so very largely because they were great compromisers.

- Learned Hand, testimony before the United States Congress, Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, hearing on the Establishment of a Commission on Ethics in Government (1951).

- America is history's exception. It began as a republic founded by European migrants. Like the homogenous citizens of most other nations, they were likely on a trajectory to incorporate racial sameness as the mark of citizenship. But the ultimate logic of America’s unique Constitution was different. So the United States steadily evolved to define Americans by their shared values, not by their superficial appearance. Eventually, anyone who was willing to give up his prior identity and assume a new American persona became American. The United States has always cherished its "melting pot" ethos of e pluribus unum — of blending diverse peoples into one through assimilation, integration, and intermarriage.

- Victor Davis Hanson, "America: History’s Exception" (13 June 2016), National Review Online

- If the Constitution is to be construed to mean what the majority at any given period in history wish the Constitution to mean, why a written Constitution and deliberate process of amendment?

- Frank J. Hogan, Presidential address to the American Bar Association, San Francisco (July 10, 1939); reported in the Texas Bar Journal (1939), volume 2, p. 306.

- We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is, and the judiciary is the safeguard of our liberty and of our property under the Constitution.

- Charles Evans Hughes, speech before the Chamber of Commerce, Elmira, New York (May 3, 1907); reported in Addresses and Papers of Charles Evans Hughes, Governor of New York, 1906–1908 (1908), p. 139.

- While the Declaration was directed against an excess of authority, the Constitution was directed against anarchy.

- Robert H. Jackson, The Struggle for Judicial Supremacy: A Study in Crisis in American Power Politics (1941), p. 8.

- Amendments to the Constitution ought to not be too frequently made; . . . continually tinkered with it would lose all its prestige and dignity, and the old instrument would be lost sight of altogether in a short time.

- Andrew Johnson, speech in front of the White House (February 22, 1866); Andrew Johnson Papers, Library of Congress.

- As apt and applicable as the Declaration of Independence is today, we would do well to honor that other historic document drafted in this hall--the Constitution of the United States. For it stressed not independence but interdependence--not the individual liberty of one but the indivisible liberty of all.

- The Irish were not wanted there [when his grandfather came to Boston]. Now an Irish Catholic is president of the United States … There is no question about it. In the next 40 years a Negro can achieve the same position that my brother has. … We have tried to make progress and we are making progress … we are not going to accept the status quo. … The United States Government has taken steps to make sure that the constitution of the United States applies to all individuals.

- Robert F. Kennedy, as quoted in AP report with lead summarizing of remarks stating "Robert F. Kennedy said yesterday that the United States — despite Alabama violence — is moving so fast in race relations a Negro could be President in 40 years." "Negro President in 40 Years?" in Montreal Gazette (27 May 1961)

- In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the "unalienable Rights" of "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

- Martin Luther King Jr., "I Have a Dream" speech, August 28, 1963

- America failed the first test in November 2016, when we elected a president with a dubious allegiance to democratic norms. Donald Trump’s surprise victory was made possible not only by public disaffection but also by the Republican Party’s failure to keep an extremist demagogue within its own ranks from gaining the nomination. How serious is the threat now? Many observers take comfort in our Constitution, which was designed precisely to thwart and contain demagogues like Donald Trump. Our Madisonian system of checks and balances has endured for more than two centuries. It survived the Civil War, the Great Depression, the Cold War, and Watergate. Surely, then, it will be able to survive Trump. We are less certain. Historically, our system of checks and balances has worked pretty well—but not, or not entirely, because of the constitutional system designed by the founders. Democracies work best—and survive longer—where constitutions are reinforced by unwritten democratic norms. Two basic norms have preserved America’s checks and balances in ways we have come to take for granted: mutual toleration, or the understanding that competing parties accept one another as legitimate rivals, and forbearance, or the idea that politicians should exercise restraint in deploying their institutional prerogatives. These two norms undergirded American democracy for most of the twentieth century. Leaders of the two major parties accepted one another as legitimate and resisted the temptation to use their temporary control of institutions to maximum partisan advantage. Norms of toleration and restraint served as the soft guardrails of American democracy, helping it avoid the kind of partisan fight to the death that has destroyed democracies elsewhere in the world, including Europe in the 1930s and South America in the 1960s and 1970s. Today, however, the guardrails of American democracy are weakening. The erosion of our democratic norms began in the 1980s and 1990s and accelerated in the 2000s. By the time Barack Obama became president, many Republicans, in particular, questioned the legitimacy of their Democratic rivals and had abandoned forbearance for a strategy of winning by any means necessary. Donald Trump may have accelerated this process, but he didn’t cause it. The challenges facing American democracy run deeper. The weakening of our democratic norms is rooted in extreme partisan polarization—one that extends beyond policy differences into an existential conflict over race and culture. America’s efforts to achieve racial equality as our society grows increasingly diverse have fueled an insidious reaction and intensifying polarization. And if one thing is clear from studying breakdowns throughout history, it’s that extreme polarization can kill democracies. There are, therefore, reasons for alarm. Not only did Americans elect a demagogue in 2016, but we did so at a time when the norms that once protected our democracy were already coming unmoored. But if other countries’ experiences teach us that that polarization can kill democracies, they also teach us that breakdown is neither inevitable nor irreversible. Drawing lessons from other democracies in crisis, this book suggests strategies that citizens should, and should not, follow to defend our democracy.

- Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt (2018) How Democracies Die. New York: Crown.

- Don't interfere with anything in the Constitution. That must be maintained, for it is the only safeguard of our liberties.

- Abraham Lincoln, speech at Kalamazoo, Michigan (27 August 1856); reported in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953), volume 2, p. 366

- The right of property in a slave is not distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution... I believe that the Supreme Court and the advocates of that decision may search in vain for the place in the Constitution where the right of a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed.

- Abraham Lincoln, Fifth Lincoln–Douglas Debate (7 October 1858), Galesburg, Illinois

- It is easy to demonstrate that 'our Fathers, who framed this government under which we live', looked on slavery as wrong, and so framed it and everything about it as to square with the idea that it was wrong, so far as the necessities arising from its existence permitted. In forming the Constitution they found the slave trade existing; capital invested in it; fields depending upon it for labor, and the whole system resting upon the importation of slave-labor. They therefore did not prohibit the slave trade at once, but they gave the power to prohibit it after twenty years. Why was this? What other foreign trade did they treat in that way? Would they have done this if they had not thought slavery wrong? Another thing was done by some of the same men who framed the Constitution, and afterwards adopted as their own act by the first Congress held under that Constitution, of which many of the framers were members; they prohibited the spread of Slavery into Territories. Thus the same men, the framers of the Constitution, cut off the supply and prohibited the spread of Slavery, and both acts show conclusively that they considered that the thing was wrong. If additional proof is wanting it can be found in the phraseology of the Constitution. When men are framing a supreme law and chart of government, to secure blessings and prosperity to untold generations yet to come, they use language as short and direct and plain as can be found, to express their meaning. In all matters but this of slavery the framers of the Constitution used the very clearest, shortest, and most direct language. But the Constitution alludes to slavery three times without mentioning it once! The language used becomes ambiguous, roundabout, and mystical. They speak of the 'immigration of persons', and mean the importation of slaves, but do not say so. In establishing a basis of representation they say 'all other persons', when they mean to say slaves — why did they not use the shortest phrase? In providing for the return of fugitives they say 'persons held to service or labor'. If they had said slaves it would have been plainer, and less liable to misconstruction. Why didn't they do it. We cannot doubt that it was done on purpose. Only one reason is possible, and that is supplied us by one of the framers of the Constitution — and it is not possible for man to conceive of any other — they expected and desired that the system would come to an end, and meant that when it did, the Constitution should not show that there ever had been a slave in this good free country of ours!

- Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Connecticut (6 March 1860)

- This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing Government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it. I cannot be ignorant of the fact that many worthy and patriotic citizens are desirous of having the National Constitution amended. While I make no recommendation of amendments, I fully recognize the rightful authority of the people over the whole subject, to be exercised in either of the modes prescribed in the instrument itself; and I should, under existing circumstances, favor rather than oppose a fair opportunity being afforded the people to act upon it. I will venture to add that to me the convention mode seems preferable, in that it allows amendments to originate with the people themselves, instead of only permitting them to take or reject propositions originated by others not especially chosen for the purpose, and which might not be precisely such as they would wish to either accept or refuse.

- Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address (4 March 1861).

- Contrary to the frequent presentations by modern liberals, the 'three-fifths clause' of the Constitution was the anti-slavery movement's response to slave owners who wanted their slaves as property, except when it came to counting population for representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. In which case the slave owners wanted them counted as people. Thus the move to block slave owners’ power by reducing a slave to “three-fifths” of a person, with the objective of eventually phasing out slavery altogether. Alas, the birth of political factions, parties, took place rapidly, to the chagrin of President George Washington. In the battles between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton the Democratic-Republican Party, the ancestor of today’s Democrats was born. And the pro-slavery, judge-people-by-skin-color faction became the central, and as it played out, perpetual, driving force of the Democratic Party.

- Jeffrey Lord, as quoted in "Will GOP Demand Obama Apology for Slavery?" (10 February 2015), Conservative Review.

- Here we stan' on the Constitution, by thunder!

It's a fact o' wich ther's bushils o' proofs;

Fer how could we trample on 't so, I wonder,

Ef 't worn't thet it's ollers under our hoofs?'

Sez John C. Calhoun, sez he.- James Russell Lowell, The Bigelow Papers, Series I (1848).

- Your constitution is all sail and no anchor. As I said before, when a society has entered on this downward progress, either civilisation or liberty must perish. Either some Caesar or Napoleon will seize the reins of government with a strong hand; or your republic will be as fearfully plundered and laid waste by barbarians in the twentieth Century as the Roman Empire was in the fifth;—with this difference, that the Huns and Vandals who ravaged the Roman Empire came from without, and that your Huns and Vandals will have been engendered within your own country by your own institutions.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, letter to Henry Stephens Randall (May 23, 1857); reported in Thomas Pinney, , ed., The Letters of Thomas Babington Macaulay (1981), volume 6, p. 96

- American devotion to the principle of fundamental law gave the Constitution its odor of sanctity, and the American bent for evading contradictions by assigning values to separate compartments allowed the Supreme Court to assume the priestly mantle.

- Robert G. McCloskey, The American Supreme Court (1960; 1974), p. 14

- The U.S. Constitution also bent over backwards to avoid using the term 'slave' or 'slavery' in the document, but the pro-slavery CSA apparently didn't have a problem calling a spade a spade.

- Jim McCullough, "The Constitution of the Confederate States of America: What was changed? And why?" (July 2006)

- Those who betray or subvert the Constitution are guilty of sedition and/or treason, are domestic enemies and should and will be punished accordingly. It also stands to reason that anyone who sympathizes with the enemy or gives aid or comfort to said enemy is likewise guilty. I have sworn to uphold and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic and I will. And I will because not only did I swear to, but I believe in what it stands for in every bit of my heart, soul and being. I know in my heart that I am right in my struggle, Steve. I have come to peace with myself, my God and my cause. Blood will flow in the streets, Steve. Good vs. Evil. Free Men vs. Socialist Wannabe Slaves. Pray it is not your blood, my friend.

- The Constitution should only be amended to address our nation's most pressing problems that can't be solved with legislation.

- Barack Obama, as quoted in "The Constitution, Designed to Change, Rarely Does" (4 December 2008), by Jennifer S. Forsyth, The Wall Street Journal

- [T]hat document is a lot of things, genuinely revolutionary, and the foundation of an improbably long-lived democracy. But it's also infused with, and inextricably linked to slavery, and a legacy of racial inequality. From the three-fifths clause, to the fugitive slave clause. The constitution both codified slavery, and made it harder for individuals to escape it. And the fact the Constitution is infused with racism does not mean it's canceled. It's not a YouTuber who's just now realized it was wrong to do black face for 14 years. And it definitely doesn't mean that kids shouldn't learn about it. But they should be taught to see it as an imperfect document with imperfect authors, who both extolled the ideas of freedom for all, while at the same time, codifying slavery.

- John Oliver, “U.S. History”, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, (Aug 3, 2020)

- During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the pro-slavery members, who eventually became the Democratic Party five years later, argued that slaves should be counted as citizens when considering the number of congressional seats their state would receive. They made this argument even though they had no intentions of giving the slaves the same rights afforded to the white citizens of their states. The anti-slavery members, who eventually became the Republican Party, strongly opposed this racist proposal. To finalize the constitution and not give in totally to the pro-slavery members, they reached a compromise with a three-fifths clause. Under the new clause, the pro-slavery states could only count the slaves three-fifths of a person when determining how many congressional seats their state would receive. Shortly after this matter was settled, Pierce Butler, a representative from the slave state of South Carolina argued that the document should include a Fugitive Slave Clause. Under his proposed recommendation, runaway slaves would be classified as criminals and treated as such. To avoid any further delays in finalizing the constitution, the constitutional convention approved the clause but stated the federal government would not enforce this clause, enforcement would be the responsibility of the individual slave state.

- This nation was created to give expression, validity and purpose to our spiritual heritage—the supreme worth of the individual. In such a nation—a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal—racial discrimination has no place. It can hardly be reconciled with a Constitution that guarantees equal protection under law to all persons. In a deeper sense, too, it is immoral and unjust. As to those matters within reach of political action and leadership, we pledge ourselves unreservedly to its eradication.

- Republican Party Platform of 1960 (July 25, 1960).

- The United States Constitution has proven itself the most marvelously elastic compilation of rules of government ever written.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio address (March 2, 1930); reported in Public Papers of Governor Roosevelt (1930), p. 710.

- I hope your committee will not permit doubts as to constitutionality, however reasonable, to block the suggested legislation.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, letter to Representative Samuel B. Hill (July 6, 1935); published in The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1935 (1938), p. 298.

- The people themselves must be the ultimate makers of their own Constitution, and where their agents differ in their interpretations of the Constitution the people themselves should be given the chance, after full and deliberate judgment, authoritatively to settle what interpretation it is that their representatives shall thereafter adopt as binding.

- Theodore Roosevelt, My Confession of Faith, Speech Before the Progressive Party National Convention (6 August 1912). Source: Teaching American History. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024.

- The Constitution explicitly forbids the requiring of any religious test as a qualification for holding office. To impose such a test by popular vote is as bad as to impose it by law. To vote either for or against a man because of his creed is to impose upon him a religious test and is a clear violation of the spirit of the Constitution.

- Theodore Roosevelt, "Address to the Knights of Columbus" (12 October 1915)

- The United States Constitution shields American citizens from U.S. government overreach even when the activities take place in a foreign embassy in a foreign country

- Richard Roth CIA sued over alleged spying on lawyers, journalists who met Assange (2 minute readAugust 15, 20221:20 PM PDTLast Updated 3 months ago)

- [T]o countless numbers of thinkers and unthinking alike the new Constitution became fraught with supernal wisdom and endowed with extraordinary intrinsic properties and potentialities.

- Frank I. Schechter, 'The Early History of the Tradition of the Constitution', The American Political Science Review, Vol. 9, No. 4 (November 1915), p. 719

- Secession was illegal. The Union was and is perpetual. The founders intended it so. Madison's letter to Hamilton, 'The Constitution requires an adoption in toto, and for ever', during the New York ratification debates demonstrate that decisively. But on an even more profound scale, the ratification process itself demonstrates that the founders intended the permanence and strength of the Union. They had had it with powerful states. That's why the founders stated in Article VII that ratification had to happen in special conventions, not the state legislatures. If the founders had left it to the state legislatures, those legislatures would have rejected the document out of hand. But the special ratifying conventions were different. They were composed of delegates elected by 'We The People' of each state, not the state itself. In addition, the states liberalized voting rules by getting rid of the property qualifications. This was a special one-time-only thing in order to ensure the broadest possible participation to select delegates in order to make it as democratic as the 18th century mindset would allow. In the north, five states even allowed blacks the right to vote.

- Christopher Shelley, "Chat-Room" (7 April 2014), Crossroads.

- When the Constitution says 'We the People' that's not just a rhetorical flourish. That's a description of the nature of the Union. See Akhil Reed Amar's excellent book The American Constitution: A Biography for this interpretation... Why did they do this? Because the founders did not want the national government to be a creature of the states. They had had one of those in the Articles of Confederation, and it didn’t work for them. That’s why the Constitution is very clear in Article VI that it supersedes the states; that’s why all federal and state officials MUST swear or affirm their allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, look it up. The nature of the American Union, then, is based on popular sovereignty, the idea that the people have the right to rule. The American people spoke during ratification and created a new federal government in which they vested their sovereignty. The federal government is not merely an agent of the states, as John C. Calhoun asserted; it was not and is not a compact between states. The founders specifically avoided that. So, if a state wants to leave the Union, the only possible way is for 'We the People' to agree to let it go. But there is no specific mechanism for secession in the constitution as it stands. And really, there is no way to read a right of secession into its text. It isn't there, and that's because the Founders never intended for states to break away. Therefore, secession, which would effectively destroy the Constitution, was and is illegal. And Lincoln was simply carrying out his oath of office to 'preserve, protect, and defend' it.

- Christopher Shelley, "Chat-Room" (7 April 2014), Crossroads.

- The U.S. Constitution of 1787 helped advance the transition to modern democracy. It did this in a surprising way by purging many elements of early democracy that had existed in state constitutions as late as the 1780s. After 1787 representatives could no longer be bound by mandates or instructions, whereas this had been common in colonial assemblies as well as in early state assemblies. Likewise, elections would occur less frequently, whereas even after 1776, in state legislatures elections most often occurred annually. Individual states would also be compelled to accept central decisions with regard to taxation and defense. Unlike in early democracy, the Constitution allowed for the creation of a powerful central state bureaucracy, and it offered a form of political participation that was broad but also only episodic and that involved governance across a very large territory. We are still in the process of learning whether this experiment can work.

- David Stasavage, The Decline and Rise of Democracy: A Global History from Antiquity to Today (2020), pp. 19-20

- The old Soviet constitution created a right to secede. The United States Constitution does not. Although some secessionists in the American South, invoking state sovereignty, claimed to find an implicit right to secede in the founding document, it was more common to invoke an extra-textual 'right to secede' said to be enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. In any case, no serious scholar or politician now argues that a right to secede exists under United States constitutional law. It is generally agreed that such a right would undermine the spirit of the original document, one that encourages the development of constitutional provisions that prevent the defeat of the basic enterprise of democratic self-government.

- Well, the Constitution has not yet been pregnant.

- Gore Vidal, as quoted in "Jah" (15 August 2004), Da Ali G Show.

- However the Court may interpret the provisions of the Constitution, it is still the Constitution which is the law and not the decision of the Court.

- Charles Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History (1932), volume 2, chapter 38, p. 748–49.

- One country, one constitution, one destiny.

- Daniel Webster, Speech (15 March 1837); reported in Edward Everett, ed., The Works of Daniel Webster (1851), page 349

- Most of the Constitution's Framers knew, and many said, that slavery was wrong.

- Thomas G. West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), p. 14

- [B]lacks definitely were part of "we the people" who made the Constitution of 1787.

- Thomas G. West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), p. 26

- We've had a decision that the Constitution as read by Alberto Gonzales, John Yoo and a few other very selected administration lawyers doesn't pertain the way it has pertained for 200-plus years. A very ahistorical reading of the Constitution... This is not the way America was intended to be run by its founders and it is not the interpretation of the Constitution that any of the founders as far as I read the Federalist Papers and other discussions about their views would have subscribed to. This is an interpretation of the constitution that is outlandish and as I said, clearly ahistorical.

- Lawrence Wilkerson in Interview transcript of the PBS program NOW about pre-war intelligence, PBS (3 February 2006)

- The constitution does not provide for first and second class citizens.

- Wendell Willkie, An American Program (1944), p. 8