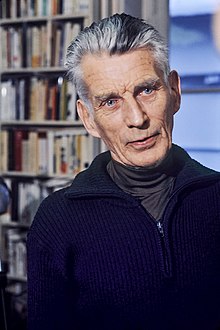

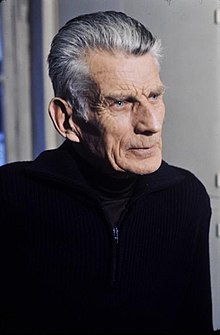

Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett (13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish playwright, novelist, poet and winner of the 1969 Nobel Prize in Literature. He wrote mainly in English and French.

Quotes

[edit]

- Spend the years of learning squandering

Courage for the years of wandering

Through a world politely turning

From the loutishness of learning.- "Gnome" in Dublin Magazine Vol. 9 (1934), p. 8

- The only sin is the sin of being born.

- As quoted in "Samuel Beckett Talks About Beckett" by John Gruen, in Vogue, (December 1969), p. 210

- Comparable to "The tragic figure represents the expiation of original sin, of the original and eternal sin of him and all his 'soci malorum,' the sin of having been born. 'Pues el delito mayor / Del hombre es haber nacido.'" from his essay Proust, quoting Pedro Calderón de la Barca's La vida es sueño (Life is a Dream).

- If by Godot I had meant God I would have said God, and not Godot.

- As quoted in The Essential Samuel Beckett: An Illustrated Biography, by Enoch Brater (revised edition, 2003) ISBN 0-500-28411-3, p. 75

- It means what it says.

- Said about Waiting for Godot, from Jonathan Croall, The Coming of Godot (2005) ISBN 1-840-02595-6, p. 91

- I grow gnomic. It is the last phase.

- The Letters of Samuel Becket 1929–1940 (2009), p. 209

- I think the next little bit of excitement is flying. I hope I am not too old to take it up seriously, nor too stupid about machines to qualify as a commercial pilot. I do not feel like spending the rest of my life writing books that no one will read. It is not as though I wanted to write them.

- The Letters of Samuel Beckett 1929–1940 (2009), p. 362

- The time-state of attainment eliminates so accurately the time-state of aspiration, that the actual seems the inevitable, and, all conscious intellectual effort to reconstitute the invisible and unthinkable as a reality being fruitless, we are incapable of appreciating our joy by comparing it with our sorrow.

- Proust (1957), p. 4

- The confusion is not my invention. We cannot listen to a conversation for five minutes without being acutely aware of the confusion. It is all around us and our only chance now is to let it in.

- Tom F. Driver, "Beckett by the Madeleine" (1961), Columbia University Forum 4 (Summer 1961): 21-25; it later appeared in Stanley A. Clayes, ed., Drama and Discussion (1967), pp. 604-7, as quoted in "Rick On Theater" 25 January 2018.

- My mother was deeply religious. So was my brother. ... The family was Protestant, but for me it was only irksome and I let it go. My brother and mother got no value from their religion when they died. At the moment of crisis it had no more depth than an old-school tie. Irish Catholicism is not attractive, but it is deeper. When you pass a church on an Irish bus, all the hands flurry in the sign of the cross. One day the dogs of Ireland will do that too and perhaps also the pigs.”

- Tom F. Driver, Op. cit.

- Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness.

- "Samuel Beckett Talks About Beckett", Vogue Magazine, 1969

Murphy (1938)

[edit]

- Grove Press, 1994, ISBN 0-802-15037-3

Watt (1943)

[edit]

- Grove Press, 1959, ISBN 0-394-17216-7

- God is a witness that cannot be sworn.

- Part I, p. 4

- Personally of course I regret everything. Not a word, not a deed, not a thought, not a need, not a grief, not a joy, not a girl, not a boy, not a doubt, not a trust, not a scorn, not a lust, not a hope, not a fear, not a smile, not a tear, not a name, not a face, no time, no place, that I do not regret, exceedingly. An ordure, from beginning to end.

- Part I, p. 37

- The long blue days, for his head, for his side, and the little paths for his feet, and all the brightness to touch and gather. Through the grass the little mosspaths, bony with old roots, and the trees sticking up, and the flowers sticking up, and the fruit hanging down, and the white exhausted butterflies, and the birds never the same darting all day long into hiding. And all the sounds, meaning nothing. Then at night rest in the quiet house, there are no roads, no streets any more, you lie down by a window opening on refuge, the little sounds come that demand nothing, ordain nothing, explain nothing, propound nothing, and the short necessary night is soon ended, and the sky blue again all over the secret places where nobody ever comes, the secret places never the same, but always simple and indifferent, always mere places, sites of a stirring beyond coming and going, of a being so light and free that it is as the being of nothing.

- Part I, p. 39

- We are no longer the same, you wiser but not sadder, and I sadder but not wiser, for wiser I could hardly become without grave personal inconvenience, whereas sorrow is a thing you can keep adding to all your life long, is it not, like a stamp or an egg collection, without feeling very much the worse for it, is it not.

- Part I, p. 50

- To whom, Watt wondered, was this arrangement due? To Mr. Knott himself? Or to some other person, to a past domestic perhaps of genius for example, or a professional dietician? And if not to Mr. Knott himself but to some other person, (or of course persons), did Mr. Knott know that such an arrangement existed, or did he not? [...] Twelve possibilities occurred to Watt, in this connexion:

1. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that he was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

2. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, but knew who was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

3. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that he was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know that any such arrangement existed, and was content.

4. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, but knew who was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

5. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know who was responsible for the arrangement, nor that any such arrangement existed, and was content.

6. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, nor knew who was responsible for the arrangement, nor knew that any such arrangement existed, and was content.

7. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know who was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

8. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, nor knew who was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

9. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, but knew who was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

10. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, but knew that he was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

11. Mr. Knott was responsible for the arrangement, but knew who was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know that any such arrangement existed, and was content.

12. Mr. Knott was not responsible for the arrangement, but knew that he was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know that such an arrangement existed, and was content.

Other possibilities occurred to Watt, in this connexion, but he put them aside, and quite out of his mind, as unworthy of serious consideration, for the time being.- pp. 71-2

- For the only way one can speak of nothing is to speak of it as though it were something, just as the only way one can speak of God is to speak of him as though he were a man, which to be sure he was, in a sense, for a time, and as the only way one can speak of man, even our anthropologists have realized that, is to speak of him as though he were a termite.

- Part II, p. 77

- But he had turned, little by little, a disturbance into words, he had made a pillow of old words, for his head.

- Part II, p. 117

- But he had hardly felt the absurdity of those things, on the one hand, and the necessity of those others, on the other (for it is rare that the feeling of absurdity is not followed by the feeling of necessity), when he felt the absurdity of those things of which he had just felt the necessity (for it is rare that the feeling of necessity is not followed by the feeling of absurdity).

- Part II, p. 133

- Consider: the darkening ease, the brightening trouble; the pleasure pleasure because it was, the pain pain because it shall be; the glad acts grown proud, the proud acts growing stubborn; the panting and trembling towards a being gone, a being to come; and the true true no longer, and the false true not yet. And to decide not to smile after all, sitting in the shade, hearing the cicadas, wishing it were night, wishing it were morning, saying, No, it is not the heart, no, it is not the liver, no, it is not the prostate, no, it is not the ovaries, no, it is muscular, it is nervous.

- Part III, p. 201

- Bid us sigh on from day to day,

And wish and wish the soul away,

Till youth and genial years are flown,

And all the life of life is gone.- Addenda, p. 248

The Expelled (1946)

[edit]

- Memories are killing. So you must not think of certain things, of those that are dear to you, or rather you must think of them, for if you don’t there is the danger of finding them, in your mind, little by little.

- They were most correct, according to their god.

- I have always been amazed at my contemporaries’ lack of finesse, I whose soul writhed from morning to night, in the mere quest of itself.

- I felt ill at ease with all this air about me, lost before the confusion of innumerable prospects.

- Yes, I don’t know why, but I have never been disappointed, and I often was in the early days, without feeling at the same time, or a moment later, an undeniable relief.

- Poor juvenile solutions, explaining nothing. No need then for caution, we may reason on to our heart’s content, the fog won’t lift.

- Does one ever know oneself why one laughs?

- The short winter’s day was drawing to a close. It seems to me sometimes that these are the only days I have ever known, and especially that most charming moment of all, just before night wipes them out.

- I don’t know why I told this story. I could just as well have told another. Perhaps some other time I’ll be able to tell another. Living souls, you will see how alike they are.

- They never lynch children, babies, no matter what they do they are whitewashed in advance.

The Calmative (1946)

[edit]- All I say cancels out, I’ll have said nothing.

- It’s to me this evening something has to happen, to my body as in myth and metamorphosis, this old body to which nothing ever happened, or so little, which never met with anything, wished for anything, in its tarnished universe, except for the mirrors to shatter, the plane, the curved, the magnifying, the minifying, and to vanish in the havoc of its images.

- I marshalled the words and opened my mouth, thinking I would hear them. But all I heard was a kind of rattle, unintelligible even to me who knew what was intended.

- How tell what remains ? But it’s the end. Or have I been dreaming, am I dreaming? No no, none of that, for dream is nothing, a joke, and significant what is worse.

- To think that in a moment all will be said, all to do again.

The End (1946)

[edit]

- I didn’t feel well, but they told me I was well enough. They didn’t say in so many words that I was as well as I would ever be, but that was the implication.

- The earth makes a sound as of sighs and the last drops fall from the emptied cloudless sky. A small boy, stretching out his hands and looking up at the blue sky, asked his mother how such a thing was possible. Fuck off, she said.

- My appearance still made people laugh, with that hearty jovial laugh so good for the health.

- It was long since I had longed for anything and the effect on me was horrible.

- I felt weak, perhaps I was.

- A mask of dirty old hairy leather, with two holes and a slit, it was too far gone for the old trick of please your honour and God reward you and pity upon me. It was disastrous.

- I tried to groan, Help! Help! But the tone that came out was that of polite conversation.

- Normally I didn’t see a great deal. I didn’t hear a great deal either. I didn’t pay attention. Strictly speaking I wasn’t there. Strictly speaking I believe I’ve never been anywhere.

- I knew it would soon be the end, so I played the part, you know, the part of — how shall I say, I don’t know.

- To contrive a little kingdom, in the midst of the universal muck, then shit on it, ah that was me all over.

- The memory came faint and cold of the story I might have told, a story in the likeness of my life, I mean without the courage to end or the strength to go on.

Three Dialogues (1949)

[edit]- "Three Dialogues" by Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit, in transition 49 (1949)

- By nature I mean here, like the naïvest realist, a composite of perceiver and perceived, not a datum, an experience. All I wish to suggest is that the tendency and accomplishment of this painting are fundamentally those of previous painting, straining to enlarge the statement of a compromise.

- Also quoted in "Beckett and Failure", in Realism, Issue 5 (June 2011)

- The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.

- Yes, yes, I am mistaken, I am mistaken.

- Don't wait to be hunted to hide, that's always been my motto.

- But is it true love, in the rectum? That’s what bothers me sometimes.

- And once again I am I will not say alone, no, that's not like me, but, how shall I say, I don't know, restored to myself, no, I never left myself, free, yes, I don't know what that means but it's the word I mean to use, free to do what, to do nothing, to know, but what, the laws of the mind perhaps, of my mind, that for example water rises in proportion as it drowns you and that you would do better, at least no worse, to obliterate texts than to blacken margins, to fill in the holes of words till all is blank and flat and the whole ghastly business looks like what is, senseless, speechless, issueless misery.

- To restore silence is the role of objects.

- There is something … more important in life than punctuality, and that is decorum.

- To him who has nothing it is forbidden not to relish filth.

- And truly it little matters what I say, this or that or any other thing. Saying is inventing. Wrong, very rightly wrong. You invent nothing, you think you are inventing, you think you are escaping, and all you do is stammer out your lesson, the remnants of a pensum one day got by heart and long forgotten, life without tears, as it is wept.

- The fact is, it seems, that the most you can hope is to be a little less, in the end, the creature you were in the beginning, and the middle.

- My life, my life, now I speak of it as of something over, now as of a joke which still goes on, and it is neither, for at the same time it is over and it goes on, and is there any tense for that? Watch wound and buried by the watchmaker, before he died, whose ruined works will one day speak of God, to the worms.

- All the things you would do gladly, oh without enthusiasm, but gladly, all the things there seems no reason for your not doing, and that you do not do! Can it be we are not free? It might be worth looking into.

- It sometimes happens and will sometimes happen again that I forget who I am and strut before my eyes, like a stranger.

- Anything worse than what I do, without knowing what, or why, I have never been able to conceive, and that doesn’t surprise me, for I never tried. For had I been able to conceive something worse than what I had I would have known no peace until I got it, if I know anything about myself.

- In me there have always been two fools, among others, one asking nothing better than to stay where he is and the other imagining that life might be slightly less horrible a little further on.

- Yes, there were times when I forgot not only who I was, but that I was, forgot to be.

- What do you expect, one is what one is, partly at least.

- To know nothing is nothing, not to want to know anything likewise, but to be beyond knowing anything, to know you are beyond knowing anything, that is when peace enters in, to the soul of the incurious seeker.

- Having heard, or more probably read somewhere, in the days when I thought I would be well advised to educate myself, or amuse myself, or stupefy myself, or kill time, that when a man in a forest thinks he is going forward in a straight line, in reality he is going in a circle, I did my best to go in a circle, hoping in this way to go in a straight line. For I stopped being half-witted and became sly, whenever I took the trouble … and if I did not go in a rigorously straight line, with my system of going in a circle, at least I did not go in a circle, and that was something.

- What I assert, deny, question, in the present, I still can. But mostly I shall use the various tenses of the past. For mostly I do not know, it is perhaps no longer so, it is too soon to know, I simply do not know, perhaps shall never know.

- I don’t like animals. It’s a strange thing, I don’t like men and I don’t like animals. As for God, he is beginning to disgust me.

- I was not made for the great light that devours, a dim lamp was all I had been given, and patience without end, to shine it on the empty shadows. I was a solid in the midst of other solids.

- I get up, go out, and everything is changed. The blood drains from my head, the noise of things bursting, merging, avoiding one another, assails me on all sides, my eyes search in vain for two things alike, each pinpoint of skin screams a different message, I drown in the spray of phenomena.

- To decompose is to live too, I know, I know, don't torment me, but one sometimes forgets. And of that life too I shall tell you perhaps one day, the day I know that when I thought I knew I was merely existing and that passion without form or stations will have devoured me down to the rotting flesh itself and that when I know that I know nothing, am only crying out as I have always cried out, more or less piercingly, more or less openly. Let me cry out then, it's said to be good for you. Yes let me cry out, this time, then another time perhaps, then perhaps a last time.

- There is a little of everything, apparently, in nature, and freaks are common.

- Not to want to say, not to know what you want to say, not to be able to say what you think you want to say, and never to stop saying, or hardly ever, that is the thing to keep in mind, even in the heat of composition.

Malone Dies (1951)

[edit]- Malone meurt (1951), translated by Beckett as Malone Dies (1956)

- Nothing is more real than nothing.

- Let me say before I go any further that I forgive nobody. I wish them all an atrocious life and then the fires and ice of hell and in the execrable generations to come an honoured name.

- The loss of consciousness for me was never any great loss.

- Or I might be able to catch one, a little girl for example, and half strangle her, three quarters, until she promises to give me my stick, give me soup, empty my pots, kiss me, fondle me, smile to me, give me my hat, stay with me, follow the hearse weeping into her handkerchief, that would be nice. I am such a good man, at bottom, such a good man, how is it that nobody ever noticed it?

- He who has waited long enough, will wait forever. And there comes the hour when nothing more can happen and nobody more can come and all is ended but the waiting that knows itself in vain.

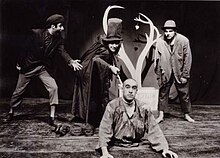

Waiting for Godot (1952)

[edit]

- 2 Acts. Premiere in Paris. First published in French and translated by the author himself into English.

Act I

[edit]

Estragon: Nothing to be done.

Vladimir: I'm beginning to come round to that opinion.

Vladimir: You should have been a poet.

Estragon: I was (Gesture towards his rags.) Isn't that obvious?

Vladimir: Come on, Gogo, return the ball, can't you, once in a way?

Estragon: (with exaggerated enthusiasm). I find this really most extraordinarily interesting.

Estragon: Let's go.

Vladimir: We can't.

Estragon: Why not?

Vladimir: We're waiting for Godot.

Estragon: (despairingly). Ah!

Estragon: What about hanging ourselves?

Vladimir: Hmm. It'd give us an erection.

Estragon: (highly excited). An erection!

Vladimir: With all that follows. Where it falls mandrakes grow. That's why they shriek when you pull them up. Did you not know that?

Estragon: Let's hang ourselves immediately!

Pozzo: The tears of the world are a constant quantity. For each one who begins to weep, somewhere else another stops. The same is true of the laugh. (He laughs.) Let us not then speak ill of our generation, it is not any unhappier than its predecessors. (Pause.) Let us not speak well of it either. (Pause.) Let us not speak of it at all. (Pause. Judiciously.) It is true the population has increased.

Vladimir: That passed the time.

Estragon: It would have passed in any case.

Vladimir: Yes, but not so rapidly.

Boy: (in a rush). Mr. Godot told me to tell you he won't come this evening but surely tomorrow.

Vladimir: We've nothing more to do here.

Estragon: Nor anywhere else.

Estragon: Well, shall we go?

Vladimir: Yes, let's go.

(They do not move.)

Act II

[edit]

Vladimir: (sententious.) To every man his little cross. (He sighs.) Till he dies. (Afterthought.) And is forgotten.

Vladimir: Let us not waste our time in idle discourse! (Pause. Vehemently.) Let us do something while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed. Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate consigned us!

Estragon: (aphoristic for once). We are all born mad. Some remain so.

Pozzo: I woke up one fine day as blind as Fortune. (Pause.) Sometimes I wonder if I'm not still asleep.

Pozzo: The blind have no notion of time. The things of time are hidden from them too.

Pozzo: (suddenly furious). Have you not done tormenting me with your accursed time! It's abominable! When! When! One day, is that not enough for you, one day he went dumb, one day I went blind, one day we'll go deaf, one day we were born, one day we shall die, the same day, the same second, is that not enough for you? (Calmer.) They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it's night once more.

Vladimir: Was I sleeping, while the others suffered? Am I sleeping now? Tomorrow, when I wake, or think I do, what shall I say of today? That with Estragon my friend, at this place, until the fall of night, I waited for Godot? That Pozzo passed, with his carrier, and that he spoke to us? Probably. But in all that what truth will there be? (Estragon, having struggled with his boots in vain, is dozing off again. Vladimir looks at him.) He'll know nothing. He'll tell me about the blows he received and I'll give him a carrot. (Pause.) Astride of a grave and a difficult birth. Down in the hole, lingeringly, the grave digger puts on the forceps. We have time to grow old. The air is full of our cries. (He listens.) But habit is a great deadener. (He looks again at Estragon.) At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on. (Pause.) I can't go on! (Pause.) What have I said?

Estragon: I can't go on like this.

Vladimir: That's what you think.

Vladimir: We are not saints, but we have kept our appointment. How many people can boast as much?

The Unnamable (1954)

[edit]

- Where now? Who now? When now? Unquestioning. I, say I. Unbelieving. Questions, hypotheses, call them that. Keep going, going on, call that going, call that on.

- The tears stream down my cheeks from my unblinking eyes. What makes me weep so? From time to time. There is nothing saddening here. Perhaps it is liquefied brain.

- Deplorable mania, when something happens, to inquire what.

- In order to obtain the optimum view of what takes place in front of me, I should have to lower my eyes a little. But I lower my eyes no more. In a word, I only see what appears close beside me, what I best see I see ill.

- What they were most determined for me to swallow was my fellow creatures. In this they were without mercy. I remember little or nothing of these lectures. I cannot have understood a great deal. But I seem to have retained certain descriptions, in spite of myself. They gave me courses on love, on intelligence, most precious, most precious. They also taught me to count, and even to reason. Some of this rubbish has come in handy on occasions, I don’t deny it, on occasions which would never have arisen if they had left me in peace. I use it still, to scratch my arse with.

- These things I say, and shall say, if I can, are no longer, or are not yet, or never were, or never will be, or if they were, if they are, if they will be, were not here, are not here, will not be here, but elsewhere.

- To go on means going from here, means finding me, losing me, vanishing and beginning again, a stranger first, then little by little the same as always, in another place, where I shall say I have always been, of which I shall know nothing, being incapable of seeing, moving, thinking, speaking, but of which little by little, in spite of these handicaps, I shall begin to know something, just enough for it to turn out to be the same place as always, the same which seems made for me and does not want me, which I seem to want and do not want, take your choice, which spews me out or swallows me up, I’ll never know, which is perhaps merely the inside of my distant skull where once I wandered, now am fixed, lost for tininess, or straining against the walls, with my head, my hands, my feet, my back, and ever murmuring my old stories, my old story, as if it were the first time.

- I, of whom I know nothing, I know my eyes are open, because of the tears that pour from them unceasingly.

- All this business of a labour to accomplish, before I can end, of words to say, a truth to recover, in order to say it, before I can end, of an imposed task, once known, long neglected, finally forgotten, to perform, before I can be done with speaking, done with listening, I invented it all, in the hope it would console me, help me to go on, allow me to think of myself as somewhere on a road, moving, between a beginning and an end, gaining ground, losing ground, getting lost, but somehow in the long run making headway.

- At no moment do I know what I’m talking about, nor of whom, nor of where, nor how, nor why, but I could employ fifty wretches for this sinister operation and still be short of the fifty-first, to close the circuit, that I know, without knowing what it means.

- The essential is to go on squirming forever at the end of the line, as long as there are waters and banks and ravening in heaven a sporting god to plague his creatures, per pro his chosen shits.

- What a joy to know where one is, and where one will stay, without being there. Nothing to do but stretch out comfortably on the rack, in the blissful knowledge you are nobody for all eternity. A pity I should have to give tongue at the same time, it prevents it from bleeding in peace, licking the lips.

- How all becomes clear and simple when one opens an eye on the within, having of course previously exposed it to the without, in order to benefit by the contrast.

- What can it matter to me, that I succeed or fail? The undertaking is none of mine, if they want me to succeed I’ll fail, and vice versa, so as not to be rid of my tormentors.

- Bah, the latest news, the latest news is not the last.

- Ah if only this voice could stop, this meaningless voice which prevents you from being nothing, just barely prevents you from being nothing and nowhere, just enough to keep alight this little yellow flame feebly darting from side to side, panting, as if straining to tear itself from its wick, it should never have been lit, or it should never have been fed, or it should have been put out, put out, it should have been let go out.

- Yes, in my life, since we must call it so, there were three things, the inability to speak, the inability to be silent, and solitude, that’s what I’ve had to make the best of.

- This place, if I could describe this place, no place around me, there’s no end to me, I don’t know what it is, it isn’t flesh, it doesn’t end, it’s like air…

- Perhaps it's done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don't know, I'll never know, in the silence you don't know, you must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on.

Texts for Nothing (1955)

[edit]

- Tears, that could be the tone, if they weren't so easy, the true tone and tenor at last.

- My keepers, why keepers, I'm in no danger of stirring an inch, ah I see, it's to make me think I'm a prisoner, frantic with corporeality, rearing to get out and away.

- Here's my life, why not, it is one, if you like, if you must, I don't say no, this evening. There has to be one, it seems, once there is speech, no need of a story, a story is not compulsory, just a life, that's the mistake I made, one of the mistakes, to have wanted a story for myself, whereas life alone is enough.

- Hamm: Can there be misery (he yawns) loftier than mine?

- Hamm: Ah, the old questions, the old answers, there's nothing like them!

- Hamm: If I could sleep I might make love. I'd go into the woods. My eyes would see … the sky, the earth. I'd run, run, they wouldn't catch me.

- Hamm: There's something dripping in my head. A heart, a heart in my head.

- Clov: When I fall I'll weep for happiness.

- Nell: Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.

Nagg: Oh?

Nell: Yes, yes, it's the most comical thing in the world. And we laugh, we laugh, with a will, in the beginning. But it's always the same thing. Yes, it's like the funny story we have heard too often, we still find it funny, but we don't laugh any more.

- Hamm: Look at the ocean!

(Clov gets down, takes a few steps towards window left, goes back for ladder, carries it over and sets it down under window left, gets up on it, turns the telescope on the without, looks at length. He starts, lowers the telescope, examines it, turns it again on the without.)

Clov: Never seen anything like that!

Hamm (anxious): What? A sail? A fin? Smoke?

Clov (looking): The light is sunk.

Hamm (relieved): Pah! We all knew that.

Clov (looking): There was a bit left.

Hamm: The base.

Clov (looking): Yes.

Hamm: And now?

Clov (looking): All gone.

Hamm: No gulls?

Clov (looking): Gulls!

Hamm: And the horizon? Nothing on the horizon?

Clov (lowering the telescope, turning towards Hamm, exasperated): What in God's name could there be on the horizon? (Pause.)

Hamm: The waves, how are the waves?

Clov: The waves? (He turns the telescope on the waves.) Lead.

Hamm: And the sun?

Clov (looking): Zero.

Hamm: But it should be sinking. Look again.

Clov (looking): Damn the sun.

Hamm: Is it night already then?

Clov (looking): No.

Hamm: Then what is it?

Clov (looking): Gray. (Lowering the telescope, turning towards Hamm, louder.) Gray! (Pause. Still louder.) GRRAY! (Pause. He gets down, approaches Hamm from behind, whispers in his ear.)

Hamm (starting): Gray! Did I hear you say gray?

Clov: Light black. From pole to pole.- An explanation of the universe outside the room of Endgame

- Hamm: What's he doing?

(CLOV raises lid of NAGG's bin, stoops, looks into it. Pause.)

Clov: He's crying.

(He closes lid, straightens up)

Hamm: Then he's living.

- Hamm: We're not beginning … to … to … mean something?

Clov: Mean something? You and I mean something?

From an Abandoned Work (1957)

[edit]- Let me go to hell, that's all I ask, and go on cursing them there, and them look down and hear me, that might take some of the shine off their bliss.

Krapp's Last Tape (1958)

[edit]

- Krapp: Perhaps my best years are gone. When there was a chance of happiness. But I wouldn't want them back. Not with the fire in me now.

- Krapp: Ah finish your booze now and get to your bed. Go on with this drivel in the morning. Or leave it at that. (Pause.) Leave it at that.

Imagination Dead Imagine (1965)

[edit]- No way in, go in, measure.

- No, life ends and no, there is nothing elsewhere, and no question now of ever finding again that white speck lost in whiteness, to see if they still lie still in the stress of that storm, or of a worse storm, or in the black dark for good, or the great whiteness unchanging, and if not what they are doing.

Worstward Ho (1983)

[edit]- All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

- Enough. Sudden enough. Sudden all far. No move and sudden all far. All least. Three pins. One pinhole. In dimmost dim. Vasts apart. At bounds of boundless void. Whence no farther. Best worse no farther. Nohow less. Nohow worse. Nohow naught. Nohow on.

A Piece of Monologue (1979)

[edit]- Birth was the death of him.

Quotes about Beckett

[edit]

- Alphabetized by author

- Why can't you write the way people want?

- Frank Beckett, in a letter to his brother Samuel, in The Letters of Samuel Beckett 1929–1940 (2009)

- Beckett does not believe in God, though he seems to imply that God has committed an unforgivable sin by not existing.

- Anthony Burgess, The Novel Now: A Guide to Contemporary Fiction (1956)

- I saw three short Beckett plays when I was sixteen, and I didn't know what it was but It hit me like a train. It was intense enough for me to never forget it. My road to Damascus.

- Paul Chan Art Is the Highest Form of Hope & Other Quotes by Artists by Phaidon (2016)

- In regard to absurdism, Samuel Beckett is sometimes considered to be the epitome of the postmodern artist … In fact, he is the aesthetic reductio ad absurdum of absurdism: no longer whistling in the dark, after waiting for Godot, he is trying to be radically silent, wordless in the dark. Beckett tries to bespeak a failure of the logos that never quite succeeds in being a failure, for to speak the failure would be a kind of success. Hence the essentially comic (hence unavoidably and ultimately affirmative) nature of his work.

- William Desmond, Philosophy and Its Others : Ways of Being and Mind (1990)

- [F]or Beckett, immobility, death, the loss of personal movement and of vertical stature...are only a subjective finality...only a means in relation to more profound end. It is a question of attaining once more the world before man...the position where movement was...under the regime of universal variation, and where light, always propagating itself, had no need to be revealed...

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The Movement-Image

- Though Godot contains all the wit and whimsicality of Murphy (minus a great deal of the old pedantry), it has one new ingredient — humanity. The novel and the play both tell us that human suffering is comic and irrational (" absurd" in the fashionable jargon), but only Godot reads like the work of a man who has actually suffered. …Even if it added nothing to Murphy, Godot would still be remarkable by the mere fact of being a popular play on an unpopular theme. It popularity is a smack in the face for all those who say that to be a skillful playwright one must first be a "man of the theatre." As far as I know, Mr Beckett may never have been backstage in his life until Godot was first performed. Yet, this first play shows consummate stagecraft. Its author has achieved a theoretical impossibility — a play in which nothing happens, that yet keeps audiences glued to their seats. What’s more, since the second act is a subtly different reprise of the first, he has written a play in which nothing happens, twice. . . . Godot makes fun even of despair. No further proof of Mr Beckett’s essential Irishness is needed. He outdoes MM Sartre and Camus in skepticism, just as Swift beat Voltaire at his own game. . . . About the only thing Godot shows consistent respect for is the music-hall low-comedy tradition.

- Vivian Mercier, on Waiting for Godot, in "The Uneventful Event" in The Irish Times (18 February 1956), p. 6; also published in The Critical Response to Samuel Beckett (1998) by Cathleen Culotta Andonian. The phrase "Nothing happens, twice" is often quoted in reference to the play, sometimes as if it were a condemnation of it, when in truth Mercier was plainly impressed by the work.

- The prospect of reading Beckett's letters quickens the blood like no other's, and one must hope to stay alive until the fourth volume is safely delivered.

- Tom Stoppard, blurb on dust jacket of The Letters of Samuel Beckett 1929–1940 (2009)

- If I hadn’t had Beckett in 1940 [in Paris, when Van Velde was strongly demoralized by the death of his wife], I’m not sure I could have stood it. I am really not sure …At that time he [Beckett] he was driven by an extremely aggressive and fiery Irish spirit. That has lessened as time has gone on … I don’t know anywhere in modern art any more faithful or more impressive picture of contemporary humanity than the one he offers us in The Unamable.

- Bram van Velde, in Conversations with Samuel Beckett and Bram van Velde (1970), edited by Charles Juliet, p. 79

- I met Beckett at my brother’s place. That was a Big meeting [circa 1938, in Paris], in capital letters. It was before war started, life was still normal. That time I was very lonely. We saw each other often. Before the war he had published already something, but his fame came in 1953. We never spoke about his work. He was a taciturn man. Sometimes a word escaped from his mouth. Sure, a word you would never forget. It would stick in your head … This friendship with Beckett is the most important experience in my life. He was fully alive for my way of working. What he could express in words, I did with my paintings.

- Bram van Velde, as quoted in "Schilder Bram van Velde in Dordrecht," in NRC Handelsblad (1979) by Paul Groot, as translated by Charlotte Burgmans

- In fact, the real problem with the thesis of A Genealogy of Morals is that the noble and the aristocrat are just as likely to be stupid as the plebeian. I had noted in my teens that major writers are usually those who have had to struggle against the odds — to "pull their cart out of the mud," as I put it — while writers who have had an easy start in life are usually second rate — or at least, not quite first-rate. Dickens, Balzac, Dostoevsky, Shaw, H. G. Wells, are examples of the first kind; in the twentieth century, John Galsworthy, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, and Samuel Beckett are examples of the second kind. They are far from being mediocre writers; yet they tend to be tinged with a certain pessimism that arises from never having achieved a certain resistance against problems.

- Colin Wilson in The Books In My Life, p. 188

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Samuel Beckett on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Samuel Beckett on Wikipedia Media related to Samuel Beckett on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samuel Beckett on Wikimedia Commons- Act I of Waiting for Godot

- Act II of Waiting for Godot

- Biography of Samuel Beckett