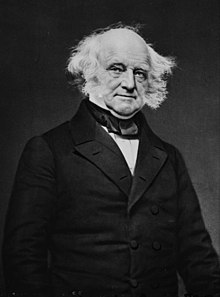

Martin Van Buren

Appearance

Martin Van Buren (December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862), nicknamed "Old Kinderhook", was the eighth president of the United States of America. He was the first president born after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the first not of British descent, and the only U.S. president whose first language was not English (it was Dutch).

| This article about a political figure is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

Quotes

[edit]- There is a power in public opinion in this country -and I thank God for it: for it is the most honest and best of all powers- which will not tolerate an incompetent or unworthy man to hold in his weak or wicked hands the lives and fortunes of his fellow-citizens.

- As quoted by William A. DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984) p. 133

Inaugural address (1837)

[edit]- Martin Van Buren's Inaugural Address (March 4, 1837)

- The practice of all my predecessors imposes on me an obligation I cheerfully fulfill—to accompany the first and solemn act of my public trust with an avowal of the principles that will guide me in performing it and an expression of my feelings on assuming a charge so responsible and vast.

- How imperious, then, is the obligation imposed upon every citizen, in his own sphere of action, whether limited or extended, to exert himself in perpetuating a condition of things so singularly happy.

- From a small community we have risen to a people powerful in numbers and in strength; but with our increase has gone hand in hand the progress of just principles.

- I tread in the footsteps of illustrious men... in receiving from the people the sacred trust confided to my illustrious predecessor.

- All the lessons of history and experience must be lost upon us if we are content to trust alone to the peculiar advantages we happen to possess.

- Present excitement will at all times magnify present dangers, but true philosophy must teach us that none more threatening than the past can remain to be overcome; and we ought (for we have just reason) to entertain an abiding confidence in the stability of our institutions and an entire conviction that if administered in the true form, character, and spirit in which they were established they are abundantly adequate to preserve to us and our children the rich blessings already derived from them, to make our beloved land for a thousand generations that chosen spot where happiness springs from a perfect equality of political rights.

- In receiving from the people the sacred trust twice confided to my illustrious predecessor, and which he has discharged so faithfully and so well, I know that I can not expect to perform the arduous task with equal ability and success. But united as I have been in his counsels, a daily witness of his exclusive and unsurpassed devotion to his country's welfare, agreeing with him in sentiments which his countrymen have warmly supported, and permitted to partake largely of his confidence, I may hope that somewhat of the same cheering approbation will be found to attend upon my path. For him I but express with my own the wishes of all, that he may yet long live to enjoy the brilliant evening of his well-spent life; and for myself, conscious of but one desire, faithfully to serve my country, I throw myself without fear on its justice and its kindness. Beyond that I only look to the gracious protection of the Divine Being whose strengthening support I humbly solicit, and whom I fervently pray to look down upon us all. May it be among the dispensations of His providence to bless our beloved country with honors and with length of days. May her ways be ways of pleasantness and all her paths be peace!

Quotes about Van Buren

[edit]

- There were wild scenes at Washington at the inauguration of the new President, dubbed by his opponent Adams as “the brawler from Tennessee.” But to the men of the West Jackson was their General, marching against the political monopoly of the moneyed classes. The complications of high politics caused difficulties for the backwoodsman. His simple mind, suspicious of his opponents, made him open to influence by more partisan and self-seeking politicians. In part be was guided by Martin Van Buren, his Secretary of State. But he relied even more heavily for advice on political cronies of his own choosing, who were known as the “Kitchen Cabinet,” because they were not office-holders. Jackson was led to believe that his first duty was to cleanse the stables of the previous regime. His dismissal of a large number of civil servants brought the spoils system, long prevalent in many states, firmly into the Federal machine.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Volume IV: The Great Democracies (1958),

- The union of Western and Southern politicians had had their revenge upon the North. The Radicalism of the frontier had won a great political contest. Jackson’s occupation of the Presidency had finally broken the “era of good feelings” which had followed the war with Britain, and by his economic policy he had split the old Republican Party of Jefferson. The Radicalism of the West was looked upon with widespread suspicion throughout the Eastern states, and Jackson’s official appointments had not been very happy. The election in 1836 of Jackson’s lieutenant, Van Buren, meant the continuation of Jacksonian policy, while the old General himself returned in triumph to. his retirement in Tennessee. The first incursions of the West into high politics had revealed the slumbering forces of democracy on the frontier and shown the inexperience of their leaders in such affairs.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Volume IV: The Great Democracies (1958),

- Accessible and a master of detail, Van Buren received advice from scores of obscure citizens and often dealt with matters that other Presidents might have left to subordinates. He dealt with army engineer Thomas Warner, for example, who went over Secretary of War Joel Poinsett's head to complain about being dismissed. Sometimes Van Buren let sentiment intrude on his decisions; when William Leggett was dying of tuberculosis, Van Buren appointed him agent to Guatemala so that he could enjoy his last months in a warm climate. And as before his tact helped in handling delicate situations, especially in appeasing Eaton when he was withdrawn from Spain. The skills that were evident in Albany were still at work in the White House.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 343

- An Englishman who visited Van Buren's White House failed to notice any luxury or ostentation. Member of Parliament James Silk Buckingham, who attended Van Buren's open house in March 1838, wrote that the White House was "greatly inferior in size and splendor to the country residences of most of the [British] nobility," and the furniture was "far from elegant of costly." "The whole air of the mansion," he said, was "unostentatious... without parade or displays,... well adapted to the simplicity and economy... of the republican institutions of the country." The servants wore no livery and Van Buren himself was dressed in a "plain suit of black." Buckingham was impressed that "every one present acted as though he felt himself to be on a footing of equality with every other person." As Buckingham noted, Van Buren in 1838 followed Andrew Jackson's policy of allowing anyone at all to attend a White House reception, and stationed no guards at the door. Van Buren himself walked to and from church alone and often rode horseback unaccompanied. A short time later, however, another British traveler, Captain Frederick Marryat, noted that Van Buren had taken a step that struck at "the very roots of their boasted equality" by stationing police at the door to "prevent the intrusion of any improper person." It was Van Buren's concession to the changing times.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 345-346

- Although democrats tried to blame the defeat on fraud, hallucination, excessive democracy, and the Mormon Church, none of these was responsible. There were more fundamental reasons for the defeat. It would have been a miracle if the Democrats had been able to survive the depression that had gripped the nation ever since Van Buren took office. Even though the Liberty party polled barely 7,000 votes, Van Buren's proslavery policies had alienated Northerners and contributed to the loss of six states that Van Buren had carried in 1836.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 373

- Van Buren himself bore much of the responsibility. In the election he was defeated by a political system and by political techniques that he more than anyone else had developed. Whig managers such as Weed and Stevens used methods that Van Buren and the Regency had perfected in New York. In 1836, he had won partly by adjusting to change better than his opponents had, but in 1840, the Whigs not the Democrats took advantage of what was new. With a national two-party system and nationwide means of communication, a national campaign with a national message was needed. With their log cabins, Tippecanoe slogans, and parades, the Whigs found the message that could produce votes. In Philip Hone's words, the "hurrah [was] heard and felt in every part of the United States." The Whigs allowed the common man to participate in their campaigns, whereas the Democrats, who had based their previous campaigns on the common man, discouraged participation. Harrison, not Van Buren, broke with tradition and went out on the campaign trail for himself. Harrison, not Van Buren, replaced Andrew Jackson as the popular hero in the eyes of the people. Even though Van Buren had created a national political party, he did not run a national campaign in 1840, but devoted most of his attention to New York as he had done in 1838, but not in 1824. Instead of adjusting his republicanism as he had in the past, he remained in 1840 chained to the Jeffersonian tradition.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 373-374

- Van Buren's personality played a part in his downfall. As Jabez Hammond observed, Van Buren lacked "those fascinating traits" and the "halo of military glory" that had made Jackson a successful President. The lack of charisma had not been a liability in state politics, but in a national election, popular appeal meant much. Hammond wrote that "the people of this country [were] fond of novelties," and Van Buren's bland personality gave them nothing to make them forget the depression. In addition, Hammond believed that Van Buren had lost his two genuinely exciting qualities- his "adroitness and skill"- during his years in the White House. This change had become apparent in the way Van Buren had run his presidency, especially in his preoccupation with the independent treasury and his failure to use patronage effectively. The skills and talents that opened the door to the White House did not last long enough to keep him there.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 374

- The one characteristic for which Van Buren was famous was the one that suggested perhaps he was not always under control. This was his political ruthlessness. He was ruthless enough to stick with William Harris Crawford long after the Georgian had suffered a disabling stroke. He kept plotting to keep John Quincy Adams from the presidency in 1825. He cleared out most of the Adams postmasters in New York in 1829. As the stories about him spread, he acquired the nicknames of "Little Magician" and "Sly Fox." His reputation and political skill gave him a place in history, but he hated the image and sought steadily to be something else. He might have been a more successful President if he had been more willing to exploit his reputation.

- Donald B. Cole, Martin Van Buren and the American Political System (1984), p. 432

- American electoral politics were forever transformed by the Whigs' imaginative presidential campaign that year. The election of 1840 was a sweeping Whig victory as Harrison easily won the presidency and both branches of Congress came under Whig control. Voter turnout was phenomenal. Roughly 80 percent of the eligible male electorate went to the polls, energized by massive parades, outdoor rallies, campaign songs, and circus-like hoopla never before witnessed by the American public. Gimmickry and humbug became hallmarks of the campaign. A widely used tactic was the rolling of large leather balls festooned with catchy slogans such as "Van, Van, Van- Van's a Used Up Man" across the rural landscape and through villages and towns.

- Edward P. Crapol, John Tyler: The Accidental President (2006) p. 17

- What have I to say against Martin Van Buren? He is an artful, cunning, intriguing, selfish, speculating lawyer, who, by holding lucrative offices for more than half his life, has contrived to amass a princely fortune... His fame is unknown to the history of our country, except as a most adroit political manager and successful officeholder... Office and money have been the gods of his idolatry; and at their shrines has the ardent worship of his heart been devoted... He can lay no claim to pre-eminent services as a statesman; nor has he ever given any evidences of superior talent, except as a political electioneer and intriguer.

- Davy Crockett, as quoted in Martin Van Buren and the Democratic Party (1959) by Robert V. Remini, p. 1

- Van Buren basically was optimistic, cheerful, quick to smile and laugh. From an early age he was an engaging conversationalist. In politics, however, he preferred to let others talk about specific issues rather than to expound his own views. In drawing others out while keeping his own opinions closely guarded, he grained a reputation as a crafty partisan who, as one colleague asserted, "rowed to his object with muffled oars." His rather unflattering nicknames, the Red Fox of Kinderhook and the Little Magician, reflected this image. He spoke cautiously, often in carefully worded phrases that left listeners in doubt about his true feelings. Van Buren was ambitious, but he was also a man of principle.

- William A. DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984), p. 123

- Canadian insurgents led by William L. Mackenzie of Ontario had been waging revolution against British rule. Thwarted in an attempt to capture Toronto, the rebels fell back to Navy Island on the Niagara River, where they established a government-in-exile committed to an independent Canada. Americans sympathetic to the revolution transported supplies to the island on the steamship Caroline. In December 1837 Canadian militia, on orders from Britain, seized the Caroline in U.S. waters, set it afire, and sent it hurtling over Niagara Falls in flames. One American was killed and several injured. In a message to Congress, President Van Buren denounced the incident as "an outrage of a most aggravated character... producing the strongest feelings of resentment on the part of our citizens in the neighborhood and on the whole border line." Although he ordered American forces to the region, he resisted cries for war with Britain and issued a proclamation of neutrality regarding the Canadian rebellion. In 1840 a Canadian, Alexander McLeod, was arrested in New York for the murder of the American killed in the Caroline affair but was later acquitted. British-American relations, aggravated further by the Aroostook War, remained strained until the signing of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842.

- William A. DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984), p. 131

- The Border between Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick had never been defined. Both the United States and Canada claimed some 12,000 square miles along the Aroostook River. The "war," though bloodless, heated up in February 1839 when Canadian authorities arrested American Rufus McIntire for attempting to expel Canadians from the disputed region. MicIntire had been acting on orders from Maine officials. Both sides immediately massed their militias along the frontier and sought support from their parent governments. As in the Caroline affair, President Van Buren resisted cries for war and instead dispatched General Winfield Scott on a peace mission to the region. Scott arranged a truce, effectively defusing the crisis pending the settlement of the border issue by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842.

- William A. DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984), p. 131

- July 24, 1862, 2 A.M., Lindenwald estate, Kinderhook, New York. During his last months, Van Buren suffered a severe attack of bronchial asthma and weakened steadily. After exchanging a few last words with his sons, he fell unconsciosu and, in the early morning hours of July 24, 1862, died of heart failure. At his request, no bells rang at his funeral, conducted at the Dutch Reformed Church in Kinderhook by the Reverend Alfonzo Potter, Episcopal bishop of Pennsylvania, and the Reverend Benjamin Van Zandt, retired pastor of the church. From the church, a long funeral procession of some 80 carriages under escort of the Kinderhook fire department slowly made its way to the village cemetery, where the rosewood coffin was placed in a protective wooden container and lowered to a grave beside that of his wife in the enclosed Van Buren family plot. In his last will and testament, executed in 1860, Van Buren divided his estate, valued at about $225,000, among his three surviving sons.

- William A. DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984), p. 133

- But, though defeated, Mr. Van Buren was not conquered. His last message contained a calm and dignified retrospect of his administration. He exhibited a clear view of our foreign relations, and showed them to be in a most happy, honorable and prosperous condition. He gave a history of the embarrassments which the government had been obliged to encounter, in consequence of the failure of the banks to perform their engagements. He insisted that the course he had recommended was the only one that could have been adopted, except that of incorporating a bank of the United States; he denounced that measure as unconstitutional, and as one which had been repeatedly repudiated by the people of the nation. He urged economy in the public expenditures; he showed that expenditures for ordinary purposes had been greatly diminished during his administration; he contended that the revenue of the government, without an increase of taxes, would be sufficient to defray all the necessary expenses; and he protested against the creation of a national debt. Although he left the enemy in possession of the field of battle, he himself retired from the arena in the spirit and with the dignity of a conqueror.

- Jabez Hammond, referring to Van Buren in the aftermath of the U.S. Presidential Election of 1840, as quoted by Ted Widmer in Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 171

- I... believe him not only deserving of my confidence but the confidence of the Nation... He... is not only well qualified, but desires to fill the highest office in the gift of the people, who in him, will find a true friend and safe repository of their rights and liberty.

- Andrew Jackson in 1829, as quoted by William A. DeGregorio in The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984) p. 133

- Martin Van Buren does not belong on anybody's list of great presidents, but he certainly belongs at the top of a sublist ranking presidents for diplomacy. Not only did he keep America out of war, but he did it twice, first with Mexico and then with England. Historians tend to glorify strong presidents, and nothing makes a president stronger than being a wartime leader. In a 1961 collection of scholarly articles on "America's Ten Greatest Presidents," for instance, half the presidents were men who had led the country into war. Yet managing to keep out of war can sometimes be an even greater achievement than rattling the war drums.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revisited: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It Into The Textbooks (2010), p. 150

- Going against the wishes of people in New York and Maine cost Van Buren reelection in 1840. A few of his closest advisers even went so far as to advise him to start a war to win back the war vote and distract public attention from the administration's difficulties, but Van Buren refused.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revisited: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It Into The Textbooks (2010), p. 152

- This democratic President's house is furnished in a style of magnificence and regal splendor that might well satisfy a monarch... This is that plain, simple, humble, hard-headed democrat whom [the people] have been taught to believe is at the head of the democratic party... He may call himself a democrat- such, no doubt, he professes to be- but then there is a great difference between names and things.

- Charles Ogle, Representative of Pennsylvania, in 1840, as quoted by William A. DeGregorio in The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (1984) p. 133

- Martin Van Buren was born in the little village of Kinderhook, in Columbia County, New York, on December 5, 1782. The son of a tavernkeeper, he received his earliest education helping his father manage the tavern where he watched the patrons eat and drink and listened to their conversation- political and otherwise. Observers later commented on his great knowledge and understanding of human nature; undoubtedly much of it was acquired during these early years. He went to the village academy for a formal education, and then to the law offices, successively, of Francis Silvester and William P. Van Ness. In 1803 he began the practice of law and slowly built a reputation for himself as a hard-working and resourceful lawyer.

- Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (1959), p. 2

- To stay alive in the New York political world one had to be clever, shrewd, and sometimes unscrupulous. It did not take the intelligent young lawyer Van Buren very long to learn what he must do to survive. Within ten years after his arrival in Albany as a senator, Van Buren gained control of the state's Republican organization. His success was due partly to his personality as a leader, partly to his ability to conceive and execute intricate plans to weaken his opponents, partly to his above-average talents as a speaker and writer, and partly to his genius for political organization.

- Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (1959), p. 3

- Martin Van Buren was probably one of the most charming men of his age. Without that charm, that ingratiating, refined and affable manner, he could never have succeeded as well as he did. Men and women vied for his companionship, and maneuvered to get him to accept invitations to their dinners. He was courteous to all- which some misinterpreted- and possessed the "high art of blending dignity with ease and suavity." His mild, open, and sociable disposition induced one observer to write that he was "as polished and captivating a person in the social circle as America has ever known..." Although endowed with no exceptional wit himself, he had a sense of humor and a keen appreciation of the humorous.

- Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (1959), p. 3

- For all the noise and head generated by the 1840 campaign, its most lasting legacy may have been one of the shortest words in the English language. In the spring of 1839, the phrase "OK" began to circulate in Boston as shorthand for "oll korrect", a slangy way of saying "all right." Early in 1840, Van Buren's supporters began to use the trendy expression as a way to identify their candidate, whom they labored to present as "Old Kinderhook," perhaps in imitation of Jackson's Old Hickory. Van Buren even wrote "OK" next to his signature. It spread like wildfire, and to this day it is a universal symbol of something elemental in the American character- informality, optimism, efficiency, call it what you will. It is spoken seven times a day by the average citizen, two billion utterances overall. And, of course, it goes well beyond our borders; if there is a single sound America has contributed to the esperanto of global communication, this is it. It is audible everywhere- in a taxicab in Paris, in a cafe in Instanbul, in the languid early seconds of the Beatles' "Revolution," when John Lennon steps up to the microphone and arrestingly calls the meeting to order. There are worse legacies that a defeated presidential candidate could claim.

- Ted Widmer, Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 140

- In truth, Van Buren was defeated, and badly. He would never hold elective office again; his career ended as prematurely as it had begun. The winds of fortune blow very strong in American politics. But despite a presidency that was disappointing in many ways, he could return to New York satisfied that he had remained true to his understanding of Democracy, imperfect as that may have been, and that most others would have fared worse under the difficult circumstances he had faced. In fact, many were about to, as the United States entered the dreariest presidential season in its history, a twenty-year drought that did not end until the watershed of the 1860 election.

- Ted Widmer, Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 141

- Van Buren shivered through the same damp inaugural ceremony that elevated and killed William Henry Harrison, then made his way north, to the home state he had not lived in for twenty years. He arrived by ship at Manhattan, and found a surprise that must have warmed his jaded heart. A huge number of the city's poor came out in the rain to greet him, conscious that, for all his imperfections, this New Yorker had somewhere represented their interests in a government where they had precious few allies.

- Ted Widmer, Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 141

- Van Buren will remain one of our lesser-known presidents, for reasons that he would understand. His presidency produced no lasting monument of social legislation, sustained several disastrous reverses, and ended with ignominious defeat after one short term. There will never be an animatronic Van Buren entertaining children at Disneyland alongside Abraham Lincoln. But still, he lives wherever people find gated communities shut to them. He lives particularly in the places far from the presidential stage where democracy does its best work- in the back rooms of union halls, fire stations, immigrant social clubs, granges, and taverns like the one he grew up in. Or even far from American shores, where courageous men and women are risking their lives every day to form opposition parties against the wishes of their governments.

- Ted Widmer, Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 170-171

- He does not need fame, or pity, but Martin Van Buren is worthy of a sober second thought. Quite simply, it's antidemocratic to expect all of our leaders to be great, or to pretend that they are once they are in office and using the trappings of the presidency for theatrical effect. It goes without saying that we need our Lincolns and Washingtons- the United States would not exist without them. But we need our Van Burens, too- the schemers and sharps working to defend people from all backgrounds against their natural predators. For democracy to stay realistic, we need to remain realistic about our leaders and what they can and cannot do. In other words, we need books about the not-quite-heroic. Van Buren is history, and this book has reached its terminus, but, as Kafka tells us, the work is never done.

- Ted Widmer, Martin Van Buren (2005), p. 171

- Politically, however, the Panic of 1837 had an enormous impact. It raised urgent questions about economic development and, in close connection, the relationship between the Treasury and the banking and currency of the country. What were the effects of English credit on the cycle of economic growth in the United States? Had the banks, by an overindulgence of the "spirit of enterprise," precipitated the pattern of overreaction and contradiction? Or were Jackson's policies chiefly to blame? Would the new president sustain these policies of reverse them? Temporarily, at least, the economy recovered from the Panic of 1837, but Van Buren's political response involved ecisions that gave basic shape to his entire presidency.

- Major L. Wilson, The Presidency of Martin Van Buren (1984), p. 43

- Van Buren is probably the first real politician in America elected to the presidency. Unlike his predecessors, he never did anything great; he never made a great speech, he never wrote a great document, he never won a great battle. He simply was the most politically astute operator that the United States had ever seen.

- Gordon Wood, interview with World Socialist Website (28 November 2019)

- In the 1830s, under Andrew Jackson and then his successor Martin Van Buren, the military moved against the Indians in the southeastern United States in what was officially called, in the title of the law authorizing it, Indian Removal. Today we'd call it ethnic cleansing.

- Howard Zinn, Truth Has a Power of Its Own (2022)

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]Categories:

- Political figure stubs

- Presidents of the United States

- 1782 births

- 1862 deaths

- Lawyers from New York (state)

- New York Free Soilers

- Ambassadors of the United States

- Diplomats of the United States

- United States presidential candidates, 1848

- United States presidential candidates, 1844

- United States presidential candidates, 1840

- United States presidential candidates, 1836

- Democratic Party (United States) politicians

- Vice Presidents of the United States

- United States Secretaries of State