Florence Nightingale

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Florence Nightingale (12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was a British nurse, a pioneer of modern nursing, and a noted statistician.

Quotes[edit]

- Can the "word" be pinned down to either one period or one church? All churches are, of course, only more or less unsuccessful attempts to represent the unseen to the mind.

- Letter quoted in Florence Nightingale in Rome : Letters Written by Florence Nightingale in Rome in the Winter of 1847-1848 (1981), edited by Mary Keele, and Suggestions for Thought : Selections and Commentaries (1994), edited by Michael D. Calabria and Janet A. MacRae, p. xiv

- You must go to Mahometanism, to Buddhism, to the East, to the Sufis & Fakirs, to Pantheism, for the right growth of mysticism.

- Letter (2 March 1853), quoted in Suggestions for Thought : Selections and Commentaries (1994), edited by Michael D. Calabria and Janet A. MacRae, p. xiii

- Women crave for being loved, not for loving. They scream out at you for sympathy all day long, they are incapable of giving any in return, for they cannot remember your affairs long enough to do so... They cannot state a fact accurately to another, nor can that other attend to it accurately enough for it to become information. Now is not all this the result of want of sympathy?... I am sick with indignation at what wives and mothers will do of the most egregious selfishness. And people call it all maternal or conjugal affection, and think it pretty to say so. No, no, let each person tell the truth from their own experience.

- Letter to Mary Clarke Mohl (13 Dec 1861), published in Florence Nightingale on Women, Medicine, Midwifery and Prostitution: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale (2005), Volume 8, edited by Lynn McDonald, p. 84

- What the horrors of war are, no one can imagine — they are not wounds and blood and fever, spotted and low, or dysentery, chronic and acute, cold and heat and famine — they are intoxication, drunken brutality, demoralization and disorder on the part of the inferior, jealousies, meanness, indifference, selfish brutality on the part of the superior.

- Letter (5 May 1855), published in Florence Nightingale : An Introduction to Her Life and Family (2001), edited by Lynn McDonald, p. 141

- I agree as to the doubtful value of competitive examination. The qualities which you really want, viz., self-control, self-reliance, habits of accurate thought, integrity and what you generally call trustworthiness, are not decided by competitive examination, which test little else than the memory.

- Letter to Lord Stanley (May 17, 1857), published in Florence Nightingale on Wars and the War Office: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale. Vol. 15 (2011), edited by Lynn McDonald, p. 265. (online on google books)

- Asceticism is the trifling of an enthusiast with his power, a puerile coquetting with his selfishness or his vanity, in the absence of any sufficiently great object to employ the first or overcome the last.

- Letter (5 September 1857), quoted in The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913) by Edward Tyas Cook, p. 369

- I use the word nursing for want of a better. It has been limited to signify little more than the administration of medicines and the application of poultices. It ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet — all at the least expense of vital power to the patient.

- Notes on Nursing (1860)

- No man, not even a doctor, ever gives any other definition of what a nurse should be than this — "devoted and obedient." This definition would do just as well for a porter. It might even do for a horse. It would not do for a policeman.

- Notes on Nursing (1860)

- Instead of wishing to see more doctors made by women joining what there are, I wish to see as few doctors, either male or female, as possible. For, mark you, the women have made no improvement — they have only tried to be men and they have only succeeded in being third-rate men.

- Letter to John Stuart Mill (12 September 1860), published in Florence Nightingale on Society and Politics, Philosophy, Science, Education (2003) edited by Lynn McDonald

- It may seem a strange principle to enunciate as the very first requirement in a Hospital that it should do the sick no harm. It is quite necessary, nevertheless, to lay down such a principle, because the actual mortality in hospitals, especially in those of large crowded cities, is very much higher than any calculation founded on the mortality of the same class of diseases among patients treated out of hospital would lead us to expect. The knowledge of this fact first induced me to examine into the influence exercised by hospital construction on the duration and death-rate of cases received into the wards; and it led me to lay before the Social Science Association a paper reprinted with the present title. Since the publication of the first edition of that paper, great advances have been made in the adoption of sound principles of hospital construction; and there are already a number of examples of new hospitals realizing all, or nearly all, the conditions required for the successful treatment of the sick and maimed poor.

- Notes on Hospitals 3rd Edition (1863), Preface

- God has taken away the greatest man of his generation, for Dr. Livingstone stood alone.

- Quoted in Modern Heroes of the Mission Field (1882) by William Pakenham Walsh p. 281

- Hospitals are only an intermediate stage of civilization, never intended at all even to take in the whole sick population.

- Sick-Nursing and Health-Nursing" (1893)

- You ask me why I do not write something... I think one's feelings waste themselves in words; they ought all to be distilled into actions and into actions which bring results.

- Letter to a friend, quoted in The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913) by Edward Tyas Cook, p. 94

- The Church is now more like the Scribes and Pharisees than like Christ... What are now called the "essential doctrines" of the Christian religion he does not even mention.

- As quoted in The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913) by Edward Tyas Cook, p. 392

- I never lose an opportunity of urging a practical beginning, however small, for it is wonderful how often in such matters the mustard-seed germinates and roots itself.

- Letter to a friend, quoted in The Life of Florence Nightingale Vol. II (1914) by Edward Tyas Cook, p. 406

- Law is the continuous manifestation of God's presence — not reason for believing him absent.

Great confusion arises from our using the same word law in two totally distinct senses … as the cause and the effect. It is said that to "explain away" everything by law is to enable us to do without God.

But law is no explanation of anything; law is simply a generalization, a category of facts. Law is neither a cause, nor a reason, nor a power, nor a coercive force. It is nothing but a general formula, a statistical table. Law brings us continually back to God instead of carrying us away from him.- Suggestions for Thought : Selections and Commentaries (1994), edited by Michael D. Calabria and Janet A. MacRae, p. 41

- Newton's law is nothing but the statistics of gravitation, it has no power whatever.

Let us get rid of the idea of power from law altogether. Call law tabulation of facts, expression of facts, or what you will; anything rather than suppose that it either explains or compels.- Suggestions for Thought : Selections and Commentaries (1994), edited by Michael D. Calabria and Janet A. MacRae, p. 41

- To understand God's thoughts we must study statistics, for these are the measure of His purpose.

- As quoted in Chance Rules : An Informal Guide to Probability, Risk, and Statistics (1999) by Brian Everitt, p. 137

- Though he made a joke when asked to do the right thing, he always did it. He was so much more in earnest than he appeared. He did not do himself justice.

- On Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, as quoted in Victorian England : Aspects of English and Imperial History, 1837-1901 (1973) by Lewis Charles Bernard Seaman, p. 108

- I have lived and slept in the same bed with English countesses and Prussian farm women... no woman has excited passions among women more than I have.

- As quoted in Parted Lips : Lesbian Love Quotes Through the Ages (2002) by Simone Rich

- How very little can be done under the spirit of fear.

- As quoted in The Book of Positive Quotations (2007) by John Cook, p. 479

- I have had a larger responsibility of human lives than ever man or woman had before. And I attribute my success to this — I never gave or took an excuse. Yes, I do see the difference now between me and other men. When a disaster happens, I act and they make excuses.

- Letter to Miss H. Bonham Carter, 1861. As quoted in The Gigantic Book of Teachers' Wisdom (2007) by Frank McCourt and Erin Gruwell, p. 410

- The martyr sacrifices herself (himself in a few instances) entirely in vain. Or rather not in vain; for she (or he) makes the selfish more selfish, the lazy more lazy, the narrow narrower.

- As quoted in Forever Yours (1990) by Martha Vicinus and Bea Nergaard , p. 275. Letter, c. 1867, to the scholar Benjamin Jowett.

- Perhaps it is not true to speak of God as a judge at all, or of his judgements. There does not seem to be really any evidence that His worlds are places of trial but rather schools, place of training, or that He is a judge but rather a Teacher, a Trainer, not in the imperfect sense in which men are teachers, but in the sense of His contriving and adapting His whole universe for one purpose of training every intelligent being to be perfect. … I think God would not be the Almighty, the All-Wise, the All-Good, if he were the judge, in the sense that the evangelical and Roman Catholic Christians impute judgement to him. … Our business is, I think, to understand, not to judge. What He does, as far as we know, to rule by law down to the most infinitesimally small portion of His universe, not to judge.

- As quoted in Florence Nightingale's Theology: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale (2002) by Lynn McDonald, pps. 177-179 (Add Mss 45783 ff65-67)

Cassandra (1860)[edit]

- Volume 2 of a privately printed work Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truth (written in 1852, revised in 1859)

- Perhaps, if prematurely we dismiss ourselves from this world, all may even have to be suffered through again — the premature birth may not contribute to the production of another being, which must be begun again from the beginning.

- Why have women passion, intellect, moral activity — these three — and a place in society where no one of the three can be exercised? Men say that God punishes for complaining. No, but men are angry with misery. They are irritated with women for not being happy. They take it as a personal offence. To God alone may women complain without insulting Him!

- Suffering, sad "female humanity!" What are these feelings which they are taught to consider as disgraceful, to deny to themselves? What form do the Chinese feet assume when denied their proper development? If the young girls of the "higher classes," who never commit a false step, whose justly earned reputations were never sullied even by the stain which the fruit of mere "knowledge of good and evil" leaves behind, were to speak, and say what are their thoughts employed upon, their thoughts, which alone are free, what would they say?

- By mortifying vanity we do ourselves no good. It is the want of interest in our life which produces it; by filling up that want of interest in our life we can alone remedy it. And, did we even see this, how can we make the difference? How obtain the interest which society declares she does not want, and we cannot want?

- What are novels? What is the secret of the charm of every romance that ever was written? The first thing in a good novel is to place the persons together in circumstances which naturally call out the high feelings and thoughts of the character, which afford food for sympathy between them on these points — romantic events they are called. The second is that the heroine has generally no family ties (almost invariably no mother), or, if she has, these do not interfere with her entire independence.

These two things constitute the main charm of reading novels.

- Give us back our suffering, we cry to Heaven in our hearts — suffering rather than indifferentism; for out of nothing comes nothing. But out of suffering may come the cure. Better have pain than paralysis! A hundred struggle and drown in the breakers. One discovers the new world. But rather, ten times rather, die in the surf, heralding the way to that new world, than stand idly on the shore!

- Passion, intellect, moral activity — these three have never been satisfied in a woman. In this cold and oppressive conventional atmosphere, they cannot be satisfied. To say more on this subject would be to enter into the whole history of society, of the present state of civilisation.

- The progressive world is necessarily divided into two classes — those who take the best of what there is and enjoy it — those who wish for something better and try to create it. Without these two classes the world would be badly off. They are the very conditions of progress, both the one and the other. Were there none who were discontented with what they have, the world would never reach anything better.

- Poetry and imagination begin life. A child will fall on its knees on the gravel walk at the sight of a pink hawthorn in full flower, when it is by itself, to praise God for it.

- There is a physical, not moral, impossibility of supplying the wants of the intellect in the state of civilisation at which we have arrived. The stimulus, the training, the time, are all three wanting to us; or, in other words, the means and inducements are not there.

Look at the poor lives we lead. It is a wonder that we are so good as we are, not that we are so bad. In looking round we are struck with the power of the organisations we see, not with their want of power. Now and then, it is true, we are conscious that there is an inferior organisation, but, in general, just the contrary.

- Women are never supposed to have any occupation of sufficient importance not to be interrupted, except "suckling their fools "; and women themselves have accepted this, have written books to support it, and have trained themselves so as to consider whatever they do as not of such value to the world or to others, but that they can throw it up at the first "claim of social life." They have accustomed themselves to consider intellectual occupation as a merely selfish amusement, which it is their " duty " to give up for every trifler more selfish than themselves.

- People do not go into the company of their fellow-creatures for what would seem a very sufficient reason, namely, that they have something to say to them, or something that they want to hear from them; but in the vague hope that they may find something to say.

- Society triumphs over many. They wish to regenerate the world with their institutions, with their moral philosophy, with their love. Then they sink to living from breakfast till dinner, from dinner till tea, with a little worsted work, and to looking forward to nothing but bed.

When shall we see a life full of steady enthusiasm, walking straight to its aim, flying home, as that bird is now, against the wind — with the calmness and the confidence of one who knows the laws of God and can apply them?

- The "dreams of youth" have become a proverb. That organisations, early rich, fall far short of their promise has been repeated to satiety. But is it extraordinary that it should be so? For do we ever utilise this heroism? Look how it lives upon itself and perishes for lack of food. We do not know what to do with it. We had rather that it should not be there. Often we laugh at it. Always we find it troublesome. Look at the poverty of our life! Can we expect anything else but poor creatures to come out of it?

- The family uses people, not for what they are, nor for what they are intended to be, but for what it wants them for — its own uses. It thinks of them not as what God has made them, but as the something which it has arranged that they shall be.

- At present we live to impede each other's satisfactions; competition, domestic life, society, what is it all but this? We go somewhere where we are not wanted and where we don't want to go. What else is conventional life? Passivity when we want to be active. So many hours spent every day in passively doing what conventional life tells us, when we would so gladly be at work.

And is it a wonder that all individual life is extinguished?

- We set the treatment of bodies so high above the treatment of souls, that the physician occupies a higher place in society than the school-master. The governess is to have every one of God's gifts; she is to do that which the mother herself is incapable of doing; but our son must not degrade himself by marrying the governess, nor our daughter the tutor, though she might marry the medical man.

- That man and woman have an equality of duties and rights is accepted by woman even less than by man. Behind his destiny woman must annihilate herself, must be only his complement. A woman dedicates herself to the vocation of her husband; she fills up and performs the subordinate parts in it. But if she has any destiny, any vocation of her own, she must renounce it, in nine cases out of ten.

- To have no food for our heads no food for our hearts, no food for our activity, is that nothing? If we have no food for the body, how do we cry out, how all the world hears of it, how all the newspapers talk of it, with a paragraph headed in great capital letters, DEATH FROM STARVATION! But suppose one were to put a paragraph in the Times, Death of Thought from Starvation, or Death of Moral Activity from Starvation, how people would stare, how they would laugh and wonder! One would think we had no heads nor hearts, by the total indifference of the public towards them. Our bodies are the only things of any consequence.

- Moral activity? There is scarcely such a thing possible! Everything is sketchy. The world does nothing but sketch.

- Look round at the marriages which you know. The true marriage — that noble union, by which a man and woman become together the one perfect being — probably does not exist at present upon earth.

It is not surprising that husbands and wives seem so little part of one another. It is surprising that there is so much love as there is. For there is no food for it. What does it live upon — what nourishes it? Husbands and wives never seem to have anything to say to one another. What do they talk about? Not about any great religious, social, political questions or feelings. They talk about who shall come to dinner, who is to live in this lodge and who in that, about the improvement of the place, or when they shall go to London. If there are children, they form a common subject of some nourishment. But, even then, the case is oftenest thus, — the husband is to think of how they are to get on in life; the wife of bringing them up at home.

But any real communion between husband and wife — any descending into the depths of their being, and drawing out thence what they find and comparing it — do we ever dream of such a thing? Yes, we may dream of it during the season of "passion," but we shall not find it afterwards. We even expect it to go off, and lay our account that it will. If the husband has, by chance, gone into the depths of his being, and found there anything unorthodox, he, oftenest, conceals it carefully from his wife, — he is afraid of "unsettling her opinions."

- Religious men are and must be heretics now — for we must not pray, except in a "form" of words, made beforehand — or think of God but with a prearranged idea.

- Men and women meet now to be idle. Is it extraordinary that they do not know each other, and that, in their mutual ignorance, they form no surer friendships? Did they meet to do something together, then indeed they might form some real tie.

But, as it is, they are not there, it is only a mask which is there — a mouth-piece of ready-made sentences about the "topics of the day"; and then people rail against men for choosing a woman "for her face" — why, what else do they see?

- It is very well to say "be prudent, be careful, try to know each other." But how are you to know each other?

Unless a woman had lost all pride, how is it possible for her, under the eyes of all her family, to indulge in long exclusive conversations with a man? "Such a thing" must not take place till after her "engagement." And how is she to make an engagement, if "such a thing" has not taken place?

- A girl, if she has any pride, is so ashamed of having anything she wishes to say out of the hearing of her own family, she thinks it must be something so very wrong, that it is ten to one, if she have the opportunity of saying it, that she will not.

And yet she is spending her life, perhaps, in dreaming of accidental means of unrestrained communion.

- It is thought pretty to say that "Women have no passion." If passion is excitement in the daily social intercourse with men, women think about marriage much more than men do; it is the only event of their lives. It ought to be a sacred event, but surely not the only event of a woman's life, as it is now. Many women spend their lives in asking men to marry them, in a refined way. Yet it is true that women are seldom in love. How can they be?

- Women dream till they have no longer the strength to dream; those dreams against which they so struggle, so honestly, vigorously, and conscientiously, and so in vain, yet which are their life, without which they could not have lived; those dreams go at last. All their plans and visions seem vanished, and they know not where; gone, and they cannot recall them. They do not even remember them. And they are left without the food of reality or of hope.

Later in life, they neither desire nor dream, neither of activity, nor of love, nor of intellect. The last often survives the longest. They wish, if their experiences would benefit anybody, to give them to someone. But they never find an hour free in which to collect their thoughts, and so discouragement becomes ever deeper and deeper, and they less and less capable of undertaking anything.

- It seems as if the female spirit of the world were mourning everlastingly over blessings, not lost, but which she has never had, and which, in her discouragement she feels that she never will have, they are so far off.

- Jesus Christ raised women above the condition of mere slaves, mere ministers to the passions of the man, raised them by His sympathy, to be Ministers of God. He gave them moral activity. But the Age, the World, Humanity, must give them the means to exercise this moral activity, must give them intellectual cultivation, spheres of action.

- Nothing can well be imagined more painful than the present position of woman, unless, on the one hand, she renounces all outward activity and keeps herself within the magic sphere, the bubble of her dreams; or, on the other, surrendering all aspiration, she gives herself to her real life, soul and body. For those to whom it is possible, the latter is best; for out of activity may come thought, out of mere aspiration can come nothing.

- The time is come when women must do something more than the "domestic hearth," which means nursing the infants, keeping a pretty house, having a good dinner and an entertaining party.

- The great reformers of the world turn into the great misanthropists, if circumstances or organisation do not permit them to act. Christ, if He had been a woman, might have been nothing but a great complainer. Peace be with the misanthropists! They have made a step in progress; the next will make them great philanthropists; they are divided but by a line.

The next Christ will perhaps be a female Christ. But do we see one woman who looks like a female Christ? or even like "the messenger before" her "face", to go before her and prepare the hearts and minds for her?

To this will be answered that half the inmates of Bedlam begin in this way, by fancying that they are "the Christ."

People talk about imitating Christ, and imitate Him in the little trifling formal things, such as washing the feet, saying His prayer, and so on; but if anyone attempts the real imitation of Him, there are no bounds to the outcry with which the presumption of that person is condemned.

Notes from Devotional Authors of the Middle Ages (1873-1874)[edit]

- Notes for an unpublished work Notes from Devotional Authors of the Middle Ages, Collected, Chosen, and Freely Translated by Florence Nightengale (1873), as quoted in The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913) by Edward Tyas Cook, Vol. II, Part VII, Ch. II : The Mystical Way, p. 231 - 245; also in Suggestions for Thought : Selections and Commentaries (1994), edited by Michael D. Calabria and Janet A. MacRae.

- Mysticism: to dwell on the unseen, to withdraw ourselves from the things of sense into communion with God — to endeavour to partake of the Divine nature; that is, of Holiness. When we ask ourselves only what is right, or what is the will of God (the same question), then we may truly be said to live in His light.

- What is Mysticism? Is it not the attempt to draw near to God, not by rites or ceremonies, but by inward disposition? Is it not merely a hard word for " The Kingdom of Heaven is within"? Heaven is neither a place nor a time. There might be a Heaven not only here but now. It is true that sometimes we must sacrifice not only health of body, but health of mind (or, peace) in the interest of God; that is, we must sacrifice Heaven. But "thou shalt be like God for thou shalt see Him as He is": this may be here and now, as well as there and then. And it may be for a time — then lost — then recovered — both here and there, both now and then.

- That Religion is not devotion, but work and suffering for the love of God; this is the true doctrine of Mystics — as is more particularly set forth in a definition of the 16th century: "True religion is to have no other will but God's." Compare this with the definition of Religion in Johnson's Dictionary: "Virtue founded upon reverence of God and expectation of future rewards and punishments"; in other words on respect and self-interest, not love. Imagine the religion which inspired the life of Christ "founded" on the motives given by Dr. Johnson!

Christ Himself was the first true Mystic. "My meat is to do the will of Him that sent me and to finish His work." What is this but putting in fervent and the most striking words the foundation of all real Mystical Religion? — which is that for all our actions, all our words, all our thoughts, the food upon which they are to live and have their being is to be the indwelling presence of God, the union with God; that is, with the Spirit of Goodness and Wisdom.

- Where shall I find God? In myself. That is the true Mystical Doctrine. But then I myself must be in a state for Him to come and dwell in me. This is the whole aim of the Mystical Life; and all Mystical Rules in all times and countries have been laid down for putting the soul into such a state.

That the soul herself should be heaven, that our Father which is in heaven should dwell in her, that there is something within us infinitely more estimable than often comes out, that God enlarges this "palace of our soul" by degrees so as to enable her to receive Himself, that thus he gives her liberty but that the soul must give herself up absolutely to Him for Him to do this, the incalculable benefit of this occasional but frequent intercourse with the Perfect: this is the conclusion and sum of the whole matter, put into beautiful language by the Mystics. And of this process they describe the steps, and assign periods of months and years during which the steps, they say, are commonly made by those who make them at all.

- These old Mystics whom we call superstitious were far before us in their ideas of God and of prayer (that is of our communion with God). "Prayer," says a mystic of the 16th century, "is to ask not what we wish of God, but what God wishes of us." "Master who hast made and formed the vessel of the body of Thy creature, and hast put within so great a treasure, the Soul, which bears the image of Thee": so begins a dying prayer of the 14th century. In it and in the other prayers of the Mystics there is scarcely a petition. There is never a word of the theory that God's dealings with us are to show His "power"; still less of the theory that "of His own good pleasure" He has " predestined" any souls to eternal damnation. There is little mention of heaven for self; of desire of happiness for self, none. It is singular how little mention there is either of "intercession " or of " Atonement by Another's merits." True it is that we can only create a heaven for ourselves and others "by the merits of Another," since it is only by working in accordance with God's Laws that we can do anything. But there is nothing at all in these prayers as if God's anger had to be bought off, as if He had to be bribed into giving us heaven by sufferings merely "to satisfy God's justice." In the dying prayers, there is nothing of the "egotism of death." It is the reformation of God's church — that is, God's children, for whom the self would give itself, that occupies the dying thoughts. There is not often a desire to be released from trouble and suffering. On the contrary, there is often a desire to suffer the greatest suffering, and to offer the greatest offering, with even greater pain, if so any work can be done. And still, this, and all, is ascribed to God's goodness. The offering is not to buy anything by suffering, but — If only the suppliant can do anything for God's children!

These suppliants did not live to see the " reformation" of God's children. No more will any who now offer these prayers. But at least we can all work towards such practical " reformation." The way to live with God is to live with Ideals — not merely to think about ideals, but to do and suffer for them. Those who have to work on men and women must above all things have their Spiritual Ideal, their purpose, ever present. The "mystical " state is the essence of common sense.- This last passage was published in 1913 using "The way to live with God is to live with ideas", but within the context of the statement this appears to be a typographical error, and subsequent publications quoting it in 1914, 1925 and 2010 have used "The way to live with God is to live with ideals."

The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913)[edit]

- Quotes from The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913) by Edward Tyas Cook

- I have read half your book thro' and I am immensely charmed by it. But some things I disagree with and more I do not understand. This does not apply to the characters, but to your conclusions, e.g. you say "women are more sympathetic than men." Now if I were to write a book out of my experience I should begin Women have no sympathy. Yours is the tradition. Mine is the conviction of experience. I have never found one woman who has altered her life by one iota for me or my opinions. Now look at my experience of men. A statesman, past middle age, absorbed in politics for a quarter of a century, out of sympathy with me, remodels his whole life and policy — learns a science the driest, the most technical, the most difficult, that of administration, as far as it concerns the lives of men, — not, as I learnt it, in the field from stirring experience, but by writing dry regulations in a London room by my sofa with me. This is what I call real sympathy.

- Letter to Madame Mohl (13 December 1861), pp. 13-15

- Now just look at the degree in which women have sympathy — as far as my experience is concerned. And my experience of women is almost as large as Europe. And it is so intimate too. I have lived and slept in the same bed with English Countesses and Prussian Bauerinnen [farm laborers]. No Roman Catholic Supérieure [president of a French university system known for their diverse, eclectic teaching methods] has ever had charge of women of the different creeds that I have had. No woman has excited "passions" among women more than I have. Yet I leave no school behind me. My doctrines have taken no hold among women. … No woman that I know has ever appris à apprendre [learned to learn]. And I attribute this to want of sympathy. You say somewhere that women have no attention. Yes. And I attribute this to want of sympathy. … It makes me mad, the Women's Rights talk about "the want of a field" for them — when I know that I would gladly give £500 a year [roughly $50,000 a year in 2008] for a Woman Secretary. And two English Lady Superintendents have told me the same thing. And we can't get one.

- Letter to Madame Mohl (13 December 1861)

- In one sense, I do believe I am "like a man," as Parthe [the writer's sister] says. But how? In having sympathy. … Women crave for being loved, not for loving. They scream out at you for sympathy all day long, they are incapable of giving any in return, for they cannot remember your affairs long enough to do so. … They cannot state a fact accurately to another, nor can that other attend to it accurately enough for it to become information. Now is not all this the result of want of sympathy?

- Letter to Madame Mohl (13 December 1861)

- People often say to me, You don't know what a wife and mother feels. No, I say, I don't and I'm very glad I don't. And they don't know what I feel. … I am sick with indignation at what wives and mothers will do of the most egregious selfishness. And people call it all maternal or conjugal affection, and think it pretty to say so. No, no, let each person tell the truth from his own experience.

- Letter to Madame Mohl (13 December 1861)

Misattributed[edit]

- Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness toward anyone.

- This is actually a portion of statement by the British nurse Edith Cavell the night before her execution by German forces on charges of espionage.

Quotes about Nightingale[edit]

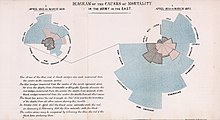

- Her statistics were more than a study, they were indeed her religion... Florence Nightingale believed — and in all the actions of her life acted upon that belief — that the administrator could only be successful if he were guided by statistical knowledge. The legislator — to say nothing of the politician — too often failed for want of this knowledge. Nay, she went further; she held that the universe — including human communities — was evolving in accordance with a divine plan; that it was man's business to endeavor to understand this plan and guide his actions in sympathy with it. But to understand God's thoughts, she held we must study statistics, for these are the measure of His purpose. Thus the study of statistics was for her a religious duty.

- Francis Galton, in The Life, Letters and Labours of Francis Galton (1924) by Karl Pearson, Vol. II

- Speaking of the cholera in the Middlesex Hospital, she said, "The prostitutes come in perpetually — poor creatures staggering off their beat! It took worse hold of them than any. One poor girl, loathsomely filthy, came in, and was dead in four hours. I held her in my arms and I heard her saying something. I bent down to hear. 'Pray God, that you may never be in the despair I am in at this time.' I said, 'Oh, my girl, are you not now more merciful than the God you think you are going to? Yet the real God is far more merciful than any human creature ever was, or can ever imagine.'"

- Elizabeth Gaskell, quoting Florence Nightingale, in letter 217 (17 October 1854), in The Letters of Mrs. Gaskell (1966)

- History can be helpful in making sense of the world we live in. It can also be fascinating, even fun. How can even the best novelist or playwright invent someone like Augustus Caesar or Catherine the Great, Galileo or Florence Nightingale? How can screenwriters create better action stories or human dramas than exist, thousand upon thousand, throughout the many centuries of recorded history? There is a thirst out there both for knowledge and to be entertained, and the market has responded with enthusiasm.

- Margaret MacMillan, The Uses and Abuses of History (2008)

- If our social arrangements were so adjusted that each person could follow that calling in life which they are by nature adapted for, what a great gainer society as a whole would be. These few who are so fortunate as to be able to follow the calling of their heart’s desire make a success of life. Florence Nightingale was one of the fortunate few, who could engage in that occupation for which she was best adapted. Florence Nightingale was a born nurse. In her was found that rare combination of heart, brain and sympathy which makes the ideal nurse. It is when one is laid low by the ravages of disease that they can appreciate to its utmost depth the value of human kindness...In the future, when the war drum will be heard no more, and the only reveille to be sounded will be that which shall call men to the peaceful walks of life, the name of Florence Nightingale will be revered, as a woman who, though delicate and far removed from want, nevertheless was willing to risk her own life, that she might bring relief to that most stupid victim of our present system, the soldier.

- Lucy Parsons, Famous Women of History: Florence Nightingale (October 22, 1905)

- The woman activist or artist born of a family-centered mother may in any case feel that her mother cannot understand or sympathize with the imperatives of her life; or that her mother has preferred and valued a more conventional daughter, or a son. In order to study nursing, Florence Nightingale was forced to battle, in the person of her mother, the restrictive conventions of upper-class Victorian womanhood, the destiny of a life in drawing rooms and country houses in which she saw women going mad "for want of something to do."

- Adrienne Rich, “Motherhood and Daughterhood”

- Emily Dickinson was always stirred by the existences of women like George Eliot or Elizabeth Barrett, who possessed strength of mind, articulateness, and energy. (She once characterized Elizabeth Fry and Florence Nightingale as "holy"-one suspects she merely meant, "great.")

- Adrienne Rich On Lies, Secrets and Silence (1979)

- Florence Nightingale lifted the vague, casual, though kindly and devoted, feeling of women into organized, efficient and invaluable service; she enlarged the nurse’s vision to sympathy for great groups outside her family or particular tribe.

- Lillian Wald, "New Aspects of Social Responsibilities (October 12, 1915)

- Her position in Indian affairs was even more extraordinary than her position at the War Office. She had never been to India, she never did go to India, and yet she was considered an expert on India and consulted on its affairs by men who had lived there all their working lives. This knowledge was the reward of her enormous labours on the Station Reports. To her bedroom had come a return from almost every military station in India, not from one Presidency or one district but the entire Peninsula. Year after year she had toiled, examining, classifying, grouping. She possessed prodigious powers of absorbing, retaining, and marshaling masses of facts, and when she had completed her task the whole vast teeming country lay before her mind's eye like a map.

- Cecil Woodham-Smith, in Florence Nightingale : 1820-1910 (1951), p. 275

External links[edit]

- BBC article

- The Life & Times of Florence Nightingale

- On-line version of Lytton Strachey's biography of Florence Nightingale

- Cassandra at the University of Aberdeen

- Full text of Florence Nightingale's book Notes on Nursing : What It Is, and What It Is Not (1898) from Project Gutenberg

- Florence Nightingale Museum

For Nightingale the statistician see also: