Abraham Lincoln: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

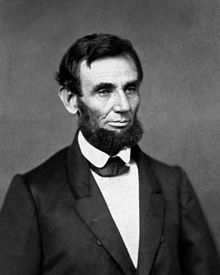

'''[[w:Abraham Lincoln|Abraham Lincoln]]''' ([[12 February]] [[1809]] – [[15 April]] [[1865]]) was the 16th [[w:President of the United States of America|President]] of the [[United States|United States of America]] and led the country during the [[American Civil War]]. |

'''[[w:Abraham Lincoln|Abraham Lincoln]]''' ([[12 February]] [[1809]] – [[15 April]] [[1865]]) was the 16th [[w:President of the United States of America|President]] of the [[United States|United States of America]] and led the country during the [[American Civil War]]. |

||

== Quotes == |

== Abraham Lincoln Quotes == |

||

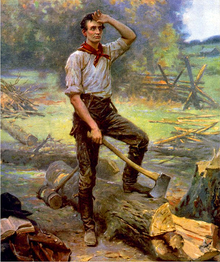

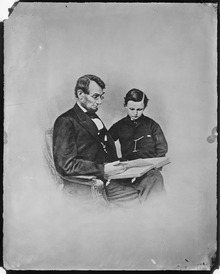

[[File:Eastman Johnson, The boyhood of Lincoln, an evening in the log hut, 1868.jpg |thumb|right|Upon the subject of [[education]], not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in.]] |

[[File:Eastman Johnson, The boyhood of Lincoln, an evening in the log hut, 1868.jpg |thumb|right|Upon the subject of [[education]], not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in.]] |

||

[[File:MaryToddLincoln.jpg|thumb|right|I can never be satisfied with anyone who would be blockhead enough to have me.]] |

[[File:MaryToddLincoln.jpg|thumb|right|I can never be satisfied with anyone who would be blockhead enough to have me.]] |

||

| Line 1,487: | Line 1,487: | ||

** [[W. J. Lampton]], ''Lincoln''. |

** [[W. J. Lampton]], ''Lincoln''. |

||

* That nation has not lived in vain which has given the world Washington and Lincoln, the best great men and the greatest good men whom history can show. * * * You cry out in the words of Bunyan, "So Valiant-for-Truth passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side." |

* That nation has not lived in vain which has given the world Washington and Lincoln, the best great men and the greatest good men whom history can show. * * * You cry out in the words of Bunyan, "So Valiant-for-Truth passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side." |

||

** [[Henry Cabot Lodge]], ''Lincoln'', address before the Massachusetts Legislature (Feb. 12, 1909). |

** [[Henry Cabot Lodge]], ''Lincoln'', address before the Massachusetts Legislature (Feb. 12, 1909). |

||

* |

* Nature, they say, doth dote,<br> And cannot make a man<br> Save on some worn-out plan<br> Repeating us by rote:<br>For him her Old World moulds aside she threw<br>And, choosing sweet clay from the breast<br> Of the unexhausted West,<br>With stuff untainted shaped a hero new. |

||

** [[James Russell Lowell]], ''A Hero New''. |

** [[James Russell Lowell]], ''A Hero New''. |

||

* Look on this cast, and know the hand<br>That bore a nation in its hold;<br>From this mute witness understand<br>What Lincoln was—how large of mould. |

* Look on this cast, and know the hand<br>That bore a nation in its hold;<br>From this mute witness understand<br>What Lincoln was—how large of mould. |

||

** [[Edmund Clarence Stedman]], ''Hand of Lincoln''. |

** [[Edmund Clarence Stedman]], ''Hand of Lincoln''. |

||

* Lo, as I gaze, the statured man,<br>Built up from yon large hand appears:<br>A type that nature wills to plan<br>But once in all a people's years. |

* Lo, as I gaze, the statured man,<br>Built up from yon large hand appears:<br>A type that nature wills to plan<br>But once in all a people's years. |

||

** [[Edmund Clarence Stedman]], ''Hand of Lincoln''. |

** [[Edmund Clarence Stedman]], ''Hand of Lincoln''. |

||

* No Cæsar he whom we lament,<br>A Man without a precedent,<br>Sent, it would seem, to do<br>His work, and perish, too. |

* No Cæsar he whom we lament,<br>A Man without a precedent,<br>Sent, it would seem, to do<br>His work, and perish, too. |

||

** [[Richard Henry Stoddard]], ''The Man We Mourn Today''. |

** [[Richard Henry Stoddard]], ''The Man We Mourn Today''. |

||

| Line 1,536: | Line 1,536: | ||

*[http://www.nps.gov/linc/ The Lincoln Memorial] Washington, DC |

*[http://www.nps.gov/linc/ The Lincoln Memorial] Washington, DC |

||

*[http://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln.html Abraham Lincoln's Assassination] |

*[http://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln.html Abraham Lincoln's Assassination] |

||

*[http://www.gyanipandit.com/abraham-lincoln-quotes-in-hindi/ Abraham Lincoln Quotes] |

|||

*[http://www.lincolnherald.com/1970articleSubstitute.html John Summerfield Staples, President Lincoln's "Substitute"] |

*[http://www.lincolnherald.com/1970articleSubstitute.html John Summerfield Staples, President Lincoln's "Substitute"] |

||

*[http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig2/lincoln-arch.html King Lincoln] (an archive of articles mostly against Lincoln) |

*[http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig2/lincoln-arch.html King Lincoln] (an archive of articles mostly against Lincoln) |

||

Revision as of 16:42, 1 April 2015

Abraham Lincoln (12 February 1809 – 15 April 1865) was the 16th President of the United States of America and led the country during the American Civil War.

Abraham Lincoln Quotes

1830s

- Upon the subject of education, not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in. That every man may receive at least a moderate education, and thereby be enabled to read the histories of his own and other countries, by which he may duly appreciate the value of our free institutions, appears to be an object of vital importance, even on this account alone, to say nothing of the advantages and satisfaction to be derived from all being able to read the Scriptures, and other works both of a religious and moral nature, for themselves.

- Address Delivered in Candidacy for the State Legislature. (9 March 1832).

- Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say, for one, that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow-men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.

- Address Delivered in Candidacy for the State Legislature. (9 March 1832).

- These capitalists generally act harmoniously and in concert to fleece the people, and now that they have got into a quarrel with themselves, we are called upon to appropriate the people's money to settle the quarrel.

- Speech to Illinois legislature (January 1837); This is "Lincoln's First Reported Speech", found in the Sangamo Journal (28 January 1837) according to McClure's Magazine (March 1896); also in Lincoln's Complete Works (1905) ed. by Nicolay and Hay, Vol. 1, p. 24.

- I have now come to the conclusion never again to think of marrying, and for this reason; I can never be satisfied with anyone who would be blockhead enough to have me.

- Letter to Mrs. Orville H. Browning (1 April 1838).

- Broken by it, I, too, may be; bow to it I never will. The probability that we may fall in the struggle ought not to deter us from the support of a cause we believe to be just; it shall not deter me.

- Speech of the Sub-Treasury (1839), Collected Works 1:178

- Variant (misspelling): The probability that we may fail in the struggle ought not to deter us from the support of a cause we believe to be just; and it shall not deter me.

The Lyceum Address (1838)

- The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions : Lincoln's address to the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois (27 January 1838)

- We find ourselves under the government of a system of political institutions, conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us. We, when mounting the stage of existence, found ourselves the legal inheritors of these fundamental blessings. We toiled not in the acquirement or establishment of them; they are a legacy bequeathed us by a once hardy, brave, and patriotic, but now lamented and departed, race of ancestors. Theirs was the task (and nobly they performed it) to possess themselves, and through themselves us, of this goodly land, and to uprear upon its hills and its valleys a political edifice of liberty and equal rights; 'tis ours only to transmit these—the former unprofaned by the foot of an invader, the latter undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation—to the latest generation that fate shall permit the world to know. This task gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to posterity, and love for our species in general, all imperatively require us faithfully to perform.

- At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? — Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never! — All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Buonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

- I hope I am over wary; but if I am not, there is, even now, something of ill-omen, amongst us. I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice. This disposition is awfully fearful in any and that it now exists in ours, though grating to our feelings to admit, it would be a violation of truth and an insult to our intelligence to deny.

- Accounts of outrages committed by mobs form the every-day news of the times. They have pervaded the country from New England to Louisiana, they are neither peculiar to the eternal snows of the former nor the burning suns of the latter; they are not the creature of climate, neither are they confined to the slaveholding or the non-slaveholding States. Alike they spring up among the pleasure-hunting masters of Southern slaves, and the order-loving citizens of the land of steady habits. Whatever then their cause may be, it is common to the whole country. [...] Such are the effects of mob law, and such are the scenes becoming more and more frequent in this land so lately famed for love of law and order, and the stories of which have even now grown too familiar to attract anything more than an idle remark. But you are perhaps ready to ask, "What has this to do with the perpetuation of our political institutions?" I answer, "It has much to do with it." Its direct consequences are, comparatively speaking, but a small evil, and much of its danger consists in the proneness of our minds to regard its direct as its only consequences.

- When men take it in their heads to-day, to hang gamblers, or burn murderers, they should recollect, that, in the confusion usually attending such transactions, they will be as likely to hang or burn some one who is neither a gambler nor a murderer as one who is; and that, acting upon the example they set, the mob of to-morrow, may, and probably will, hang or burn some of them by the very same mistake. And not only so; the innocent, those who have ever set their faces against violations of law in every shape, alike with the guilty, fall victims to the ravages of mob law; and thus it goes on, step by step, till all the walls erected for the defense of the persons and property of individuals, are trodden down, and disregarded.

- But all this even, is not the full extent of the evil. — By such examples, by instances of the perpetrators of such acts going unpunished, the lawless in spirit, are encouraged to become lawless in practice; and having been used to no restraint, but dread of punishment, they thus become, absolutely unrestrained. — Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane, they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much, as its total annihilation. While, on the other hand, good men, men who love tranquillity, who desire to abide by the laws and enjoy their benefits, who would gladly spill their blood in the defense of their country, seeing their property destroyed, their families insulted, and their lives endangered, their persons injured, and seeing nothing in prospect that forebodes a change for the better, become tired of and disgusted with a government that offers them no protection, and are not much averse to a change in which they imagine they have nothing to lose. Thus, then, by the operation of this mobocratic spirit which all must admit is now abroad in the land, the strongest bulwark of any government, and particularly of those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed—I mean the attachment of the people.

- Whenever this effect shall be produced among us; whenever the vicious portion of [our] population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision stores, throw printing-presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure and with impunity, depend upon it, this government cannot last. By such things the feelings of the best citizens will become more or less alienated from it, and thus it will be left without friends, or with too few, and those few too weak to make their friendship effectual. At such a time, and under such circumstances, men of sufficient talent and ambition will not be wanting to seize the opportunity, strike the blow, and overturn that fair fabric which for the last half century has been the fondest hope of the lovers of freedom throughout the world.

- Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well-wisher to his posterity swear by the blood of the Revolution never to violate in the least particular the laws of the country, and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and laws let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor—let every man remember that to violate the law is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own and his children's liberty. Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap; let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in primers, spelling-books, and in almanacs; let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay of all sexes and tongues and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars. While ever a state of feeling such as this shall universally or even very generally prevail throughout the nation, vain will be every effort, and fruitless every attempt, to subvert our national freedom.

- When I so pressingly urge a strict observance of all the laws, let me not be understood as saying there are no bad laws, or that grievances may not arise for the redress of which no legal provisions have been made. I mean to say no such thing. But I do mean to say that although bad laws, if they exist, should be repealed as soon as possible, still, while they continue in force, for the sake of example they should be religiously observed. So also in unprovided cases. If such arise, let proper legal provisions be made for them with the least possible delay, but till then let them, if not too intolerable, be borne with.

- There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law. In any case that arises, as for instance, the promulgation of abolitionism, one of two positions is necessarily true; that is, the thing is right within itself, and therefore deserves the protection of all law and all good citizens; or, it is wrong, and therefore proper to be prohibited by legal enactments; and in neither case, is the interposition of mob law, either necessary, justifiable, or excusable.

- We hope all danger may be overcome; but to conclude that no danger may ever arise would itself be extremely dangerous.

- That our government should have been maintained in its original form from its establishment until now, is not much to be wondered at. It had many props to support it through that period, which now are decayed, and crumbled away. Through that period, it was felt by all, to be an undecided experiment; now, it is understood to be a successful one.

- It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot. Many great and good men sufficiently qualified for any task they should undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would inspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or a presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle. What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon? — Never! Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored. — It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen. Is it unreasonable then to expect, that some man possessed of the loftiest genius, coupled with ambition sufficient to push it to its utmost stretch, will at some time, spring up among us? And when such a one does, it will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs.

- Often the portion of this passage on "Towering genius..." is quoted without any mention or acknowledgment that Lincoln was speaking of the need to sometimes hold the ambitions of such genius in check, when individuals aim at their own personal aggrandizement rather than the common good.

- I mean the powerful influence which the interesting scenes of the Revolution had upon the passions of the people as distinguished from their judgment. By this influence, the jealousy, envy, and avarice incident to our nature and so common to a state of peace, prosperity, and conscious strength, were for the time in a great measure smothered and rendered inactive, while the deep-rooted principles of hate, and the powerful motive of revenge, instead of being turned against each other, were directed exclusively against the British nation. And thus, from the force of circumstances, the basest principles of our nature, were either made to lie dormant, or to become the active agents in the advancement of the noblest cause — that of establishing and maintaining civil and religious liberty. But this state of feeling must fade, is fading, has faded, with the circumstances that produced it. I do not mean to say that the scenes of the Revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten, but that, like everything else, they must fade upon the memory of the world, and grow more and more dim by the lapse of time. In history, we hope, they will be read of, and recounted, so long as the Bible shall be read; but even granting that they will, their influence cannot be what it heretofore has been. Even then they cannot be so universally known nor so vividly felt as they were by the generation just gone to rest. At the close of that struggle, nearly every adult male had been a participator in some of its scenes. The consequence was that of those scenes, in the form of a husband, a father, a son, or a brother, a living history was to be found in every family—a history bearing the indubitable testimonies of its own authenticity, in the limbs mangled, in the scars of wounds received, in the midst of the very scenes related—a history, too, that could be read and understood alike by all, the wise and the ignorant, the learned and the unlearned. But those histories are gone. They can be read no more forever. They were a fortress of strength; but what invading foeman could never do, the silent artillery of time has done—the leveling of its walls. They are gone. They were a forest of giant oaks; but the all-restless hurricane has swept over them, and left only here and there a lonely trunk, despoiled of its verdure, shorn of its foliage, unshading and unshaded, to murmur in a few more gentle breezes, and to combat with its mutilated limbs a few more ruder storms, then to sink and be no more. They were pillars of the temple of liberty; and now that they have crumbled away that temple must fall unless we, their descendants, supply their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason.

- Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence. — Let those materials be moulded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws: and, that we improved to the last; that we remained free to the last; that we revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which to learn the last trump shall awaken our WASHINGTON.

Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, "the gates of hell shall not prevail against it".

1840s

- I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth. Whether I shall ever be better I can not tell; I awfully forebode I shall not. To remain as I am is impossible; I must die or be better, it appears to me.

- Letter to John T. Stuart (January 23, 1841), Collected Works 1:229-30

- I believe, if we take habitual drunkards as a class, their heads and their hearts will bear an advantageous comparison with those of any other class. There seems ever to have been a proneness in the brilliant and warm-blooded to fall into this vice.

- Address to the Springfield Washingtonian Temperance Society (22 February 1842), quoted at greater length in John Carroll Power (1889) Abraham Lincoln: His Life, Public Services, Death and Funeral Cortege.

- For several years past the revenues of the government have been unequal to its expenditures, and consequently loan after loan, sometimes direct and sometimes indirect in form, has been resorted to. By this means a new national debt has been created, and is still growing on us with a rapidity fearful to contemplate—a rapidity only reasonably to be expected in a time of war. This state of things has been produced by a prevailing unwillingness either to increase the tariff or resort to direct taxation. But the one or the other must come. Coming expenditures must be met, and the present debt must be paid; and money cannot always be borrowed for these objects. The system of loans is but temporary in its nature, and must soon explode. It is a system not only ruinous while it lasts, but one that must soon fail and leave us destitute. As an individual who undertakes to live by borrowing soon finds his original means devoured by interest, and, next, no one left to borrow from, so must it be with a government. We repeat, then, that a tariff sufficient for revenue, or a direct tax, must soon be resorted to; and, indeed, we believe this alternative is now denied by no one.

- Whig Circular (1843), reported in Richard Watson Gilder and Daniel Fish Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 1 (1905).

- It has so happened in all ages of the world, that some have laboured, and others have, without labour, enjoyed a large proportion of the fruits. This is wrong, and should not continue. To each labourer the whole product of his labour, or as nearly as possible, is a most worthy object of any good government.

- The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume I, "Fragments of a Tariff Discussion" (December 1, 1847).

- I believe it is an established maxim in morals that he who makes an assertion without knowing whether it is true or false, is guilty of falsehood; and the accidental truth of the assertion, does not justify or excuse him.

- Letter to Allen N. Ford (11 August 1846), reported in Roy Prentice Basler, ed., Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings (1990 [1946]).

- Any people anywhere being inclined and having the power have the right to rise up and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. This is a most valuable, a most sacred right — a right which we hope and believe is to liberate the world. Nor is this right confined to cases in which the whole people of an existing government may choose to exercise it. Any portion of such people that can may revolutionize and make their own of so much of the territory as they inhabit.

- Speech in the United States House of Representatives (January 12, 1848).

- Military glory,—that attractive rainbow that rises in showers of blood.

- Speech in the United States House of Representatives opposing the Mexican war (12 January 1848).

- Allow the President to invade a neighboring nation, whenever he shall deem it necessary to repel an invasion, and you allow him to do so, whenever he may choose to say he deems it necessary for such purpose, and you allow him to make war at pleasure. Study to see if you can fix any limit to his power in this respect, after having given him so much as you propose. If, to-day, he should choose to say he thinks it necessary to invade Canada, to prevent the British from invading us, how could you stop him? You may say to him, "I see no probability of the British invading us" but he will say to you, "Be silent; I see it, if you don't."

The provision of the Constitution giving the war making power to Congress was dictated, as I understand it, by the following reasons. Kings had always been involving and impoverishing their people in wars, pretending generally, if not always, that the good of the people was the object. This, our Convention understood to be the most oppressive of all Kingly oppressions; and they resolved to so frame the Constitution that no one man should hold the power of bringing this oppression upon us. But your view destroys the whole matter, and places our President where kings have always stood.- Letter, while US Congressman, to his friend and law-partner William H. Herndon, opposing the Mexican-American War (15 February 1848).

- In law it is a good policy never to plead what you need not, lest you oblige yourself to prove what you cannot.

- Letter to former Illinois Attorney General Usher F. Linder (20 February 1848).

- The true rule, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. Almost every thing, especially of governmental policy, is an inseparable compound of the two; so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.

- Speech in the House of Representatives (20 June 1848).

- Determine that the thing can and shall be done, and then we shall find the way.

- Speech in the House of Representatives (20 June 1848).

- The way for a young man to rise, is to improve himself every way he can, never suspecting that any body wishes to hinder him.

- Letter to William H Herndon (10 July 1848).

- The better part of one's life consists of his friendships.

- Letter to Joseph Gillespie (13 July 1849).

1850s

- Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser — in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.

Never stir up litigation. A worse man can scarcely be found than one who does this. Who can be more nearly a fiend than he who habitually overhauls the register of deeds in search of defects in titles, whereon to stir up strife, and put money in his pocket? A moral tone ought to be infused into the profession which should drive such men out of it.- Fragment, Notes for a Law Lecture (1 July 1850?), cited in Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works, Comprising his Speeches, Letters, State Papers, and Miscellaneous Writings, Vol. 2 (1894).

- There is a vague popular belief that lawyers are necessarily dishonest. I say vague, because when we consider to what extent confidence and honors are reposed in and conferred upon lawyers by the people, it appears improbable that their impression of dishonesty is very distinct and vivid. Yet the impression is common, almost universal. Let no young man choosing the law for a calling for a moment yield to the popular belief — resolve to be honest at all events; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer. Choose some other occupation, rather than one in the choosing of which you do, in advance, consent to be a knave.

- Fragment, Notes for a Law Lecture (1 July 1850), cited in Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works, Comprising his Speeches, Letters, State Papers, and Miscellaneous Writings, Vol. 2 (1894).

- If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B. Why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A? You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own. You do not mean color exactly? You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own. But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.

- Fragment on slavery (1 April 1854?), as quoted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953), Vol. 2, p. 222-223.

- The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves - in their separate, and individual capacities. In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, government ought not to interfere. The desirable things which the individuals of a people can not do, or can not well do, for themselves, fall into two classes: those which have relation to wrongs, and those which have not. Each of these branch off into an infinite variety of subdivisions. The first - that in relation to wrongs - embraces all crimes, misdemeanors, and nonperformance of contracts. The other embraces all which, in its nature, and without wrong, requires combined action, as public roads and highways, public schools, charities, pauperism, orphanage, estates of the deceased, and the machinery of government itself. From this it appears that if all men were just, there still would be some, though not so much, need for government.

- Fragment on Government (1 July 1854?) in "The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln", ed. Roy P. Basler, Vol. 2, p. 220-221.

- The Autocrat of all the Russias will resign his crown, and proclaim his subjects free republicans sooner than will our American masters voluntarily give up their slaves.

- Letter to George Robertson (15 August 1855).

- You enquire where I now stand. That is a disputed point. I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist. When I was at Washington I voted for the Wilmot Proviso as good as forty times, and I never heard of any one attempting to unwhig me for that. I now do more than oppose the extension of slavery.

I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes." When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics." When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be take pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy [sic].- Letter to longtime friend and slave-holder Joshua F. Speed (24 August 1855).

- If you are resolutely determined to make a lawyer of yourself, the thing is more than half done already. It is but a small matter whether you read with anyone or not. I did not read with anyone. Get the books, and read and study them till you understand them in their principal features; and that is the main thing. It is of no consequence to be in a large town while you are reading. I read at New Salem, which never had three hundred people living in it. The books, and your capacity for understanding them, are just the same in all places.... Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing.

- Letter to Isham Reavis (5 November 1855).

- We live in the midst of alarms; anxiety beclouds the future; we expect some new disaster with each newspaper we read.

- Speech at Bloomington (29 May 1856).

- Don't interfere with anything in the Constitution. That must be maintained, for it is the only safeguard of our liberties. And not to Democrats alone do I make this appeal, but to all who love these great and true principles.

- Speech at Kalamazoo, Michigan, August 27, 1856, Collected Works 1:391.

- Our government rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the government, practically just so much.

- Speech at a Republican Banquet, Chicago, Illinois, December 10, 1856; see Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 2 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), p. 532.

- Some more in this convention came from Kentucky to Illinois (instead of going to Missouri), not only to better their conditions, but also to get away from slavery. They have said so to me, and it is understood among us Kentuckians that we don't like it one bit. Now, can we, mindful of the blessings of liberty which the early men of Illinois left to us, refuse a like privilege to the free men who seek to plant Freedom's banner on our Western outposts? Should we not stand by our neighbors who seek to better their conditions in Kansas and Nebraska? Can we as Christian men, and strong and free ourselves, wield the sledge or hold the iron which is to manacle anew an already oppressed race ? "Woe unto them," it is written, "that decree unrighteous decrees and that write grievousness which they have prescribed." Can we afford to sin any more deeply against human liberty?

- From the Speech Delivered Before the First Republican State Convention of Illinois, Held at Bloomington (1856); found in Speeches & Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1865 (1894), J. M. Dent & Company, p. 56.

- Also quoted by Ida Minerva Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln: Drawn from Original Sources and Containing Many Speeches, Letters, and Telegrams Hitherto Unpublished, and Illustrated with Many Reproductions from Original Paintings, Photographs, etc, Volume 4 (1902), Lincoln History Society; and by William C. Whitney; in 'The Writings of Abraham Lincoln, v. 2' . (1905) Lapsley, Arthur Brooks, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.

- Definition of Democracy; see Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 2 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), p. 532.

- Will springs from the two elements of moral sense and self-interest.

- Speech at Springfield, Illinois (26 June 1857).

- What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, the guns of our war steamers, or the strength our gallant and disciplined army? These are not our reliance against a resumption of tyranny in our fair land. All of those may be turned against our liberties, without making us weaker or stronger for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in our bosoms. Our defense is in the preservation of the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere. Destroy this spirit, and you have planted the seeds of despotism around your own doors. Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage and you are preparing your own limbs to wear them. Accustomed to trample on the rights of those around you, you have lost the genius of your own independence, and become the fit subjects of the first cunning tyrant who rises.

- Speech at Edwardsville, Illinois (September 11, 1858); quoted in Lincoln, Abraham; Mario Matthew Cuomo, Harold Holzer, G. S. Boritt, Lincoln on Democracy (Fordham University Press, September 1, 2004), 128. ISBN 978-0823223459.

- Variant of the above quote: What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, our army and our navy. These are not our reliance against tyranny All of those may be turned against us without making us weaker for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in us. Our defense is in the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands everywhere. Destroy this spirit and you have planted the seeds of despotism at your own doors. Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage and you prepare your own limbs to wear them. Accustomed to trample on the rights of others, you have lost the genius of your own independence and become the fit subjects of the first cunning tyrant who rises among you.

- Fragment of Speech at Edwardsville, Ill., Sept. 13, 1858; quoted in Lincoln, Abraham; The Writings of Abraham Lincoln V05) p. 6-7.

- Variant of the above quote: What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, our army and our navy. These are not our reliance against tyranny All of those may be turned against us without making us weaker for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in us. Our defense is in the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands everywhere. Destroy this spirit and you have planted the seeds of despotism at your own doors. Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage and you prepare your own limbs to wear them. Accustomed to trample on the rights of others, you have lost the genius of your own independence and become the fit subjects of the first cunning tyrant who rises among you.

- Speech at Edwardsville, Illinois (September 11, 1858); quoted in Lincoln, Abraham; Mario Matthew Cuomo, Harold Holzer, G. S. Boritt, Lincoln on Democracy (Fordham University Press, September 1, 2004), 128. ISBN 978-0823223459.

- The Democracy of to-day hold the liberty of one man to be absolutely nothing, when in conflict with another man's right of property. Republicans, on the contrary, are both for the man and the dollar, but, in case of conflict, the man before the dollar. I remember once being much amused at seeing two partially intoxicated men engaged in a fight with their great-coats on, which fight, after a long and rather harmless contest, ended in each having fought himself out of his own coat, and into that of the other. If the two leading parties of this day are really identical with the two in the days of Jefferson and Adams, they have performed the same feat as the two drunken men.

- Letter of April 6, 1859, declining a Jefferson's Birthday invitation to Boston.

- Letter to H.L. Pierce and others (Springfield, Illinois, April 6, 1859), published in Essential American History: Abraham Lincoln - The Complete Papers and Writings, Biographically Annotated, The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, 2012, Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck, 86450 Münster, Germany, ISBN: 97838496200103.

- The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society. And yet they are denied and evaded, with no small show of success. One dashingly calls them ”glittering generalities.” Another bluntly calls them “self-evident lies.” And others insidiously argue that they apply to “superior races.” These expressions, different in form, are identical in object and effect – the supplanting the principles of free government, and restoring those of classification, caste and legitimacy. They would delight a convocation of crowned heads plotting against the people. They are the vanguard, the miner and sappers, of returning despotism. We must repulse them, or they will subjugate us.

- Letter to H.L. Pierce and others (Springfield, Illinois, April 6, 1859), published in Essential American History: Abraham Lincoln - The Complete Papers and Writings, Biographically Annotated, The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, 2012, Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck, 86450 Münster, Germany, ISBN: 97838496200103.

- This is a world of compensation; and he would be no slave must consent to have no slaves. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just God, can not long retain it.

- Letter to H.L. Pierce and others (Springfield, Illinois, April 6, 1859), published in Essential American History: Abraham Lincoln - The Complete Papers and Writings, Biographically Annotated, The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, 2012, Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck, 86450 Münster, Germany, ISBN: 97838496200103.

- Understanding the spirit of our institutions to aim at the elevation of men, I am opposed to whatever tends to degrade them.

- Letter to Dr. Theodore Canisius (17 May 1859).

- Negro equality! Fudge!! How long, in the government of a God, great enough to make and maintain this Universe, shall there continue to be knaves to vend, and fools to gulp, so low a piece of demagougeism as this?

- Fragments: Notes for Speeches, September 1859, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953) Vol. III; No transcripts or reports exist indicating that he ever actually used this expression in any of his speeches.

- We know, Southern men declare that their slaves are better off than hired laborers amongst us. How little they know, whereof they speak! There is no permanent class of hired laborers amongst us. Twentyfive years ago, I was a hired laborer. The hired laborer of yesterday, labors on his own account to-day; and will hire others to labor for him to-morrow. Advancement---improvement in condition---is the order of things in a society of equals. As Labor is the common burthen of our race, so the effort of some to shift their share of the burthen on to the shoulders of others, is the great, durable, curse of the race. Originally a curse for transgression upon the whole race, when, as by slavery, it is concentrated on a part only, it becomes the double-refined curse of God upon his creatures.

- Fragmentary manuscript of a speech on free labor (17 September 1859?); Source: The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (1953), vol. 3, p. 463.

- Free labor has the inspiration of hope; pure slavery has no hope. The power of hope upon human exertion, and happiness, is wonderful. The slave-master himself has a conception of it; and hence the system of tasks among slaves. The slave whom you can not drive with the lash to break seventy-five pounds of hemp in a day, if you will task him to break a hundred, and promise him pay for all he does over, he will break you a hundred and fifty. You have substituted hope, for the rod. And yet perhaps it does not occur to you, that to the extent of your gain in the case, you have given up the slave system, and adopted the free system of labor.

- Fragmentary manuscript of a speech on free labor (17 September 1859?); Source: The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (1953), vol. 3, pp. 463–464.

- I say that we must not interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists, because the Constitution forbids it, and the general welfare does not require us to do so. We must not withhold an efficient Fugitive Slave law, because the Constitution requires us, as I understand it, not to withhold such a law. But we must prevent the outspreading of the institution, because neither the Constitution nor general welfare requires us to extend it. We must prevent the revival of the African slave trade, and the enacting by Congress of a Territorial slave code. We must prevent each of these things being done by either Congresses or courts. The people of these United States are the rightful masters of both Congresses and courts, not to overthrow the Constitution, but to overthrow the men who pervert the Constitution.

- Speech at Cincinnati, Ohio, September 17, 1859; in "The Papers And Writings Of Abraham Lincoln, Volume Five, Constitutional Edition", edited by Arthur Brooks Lapsley and released as "The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Papers And Writings Of Abraham Lincoln, Volume Five, by Abraham Lincoln" by Project Gutenberg on July 5, 2009.

- "If I should do so now it occurs that he places himself somewhat upon the ground of the parable of the lost sheep which went astray upon the mountains, and when the owner of the hundred sheep found the one that was lost and threw it upon his shoulders, and came home rejoicing, it was said that there was more rejoicing over the one sheep that was lost and had been found than over the ninety and nine in the fold. The application is made by the Saviour in this parable thus: 'Verily I say unto you, there is more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner that repenteth than over ninety and nine just persons that need no repentance.' Repentance before forgiveness is a provision of the Christian system, and on that condition alone will the Republicans grant his forgiveness."

- In his Springfield address, July 17, 1858. Regarding his debate with Judge S. A. Douglas. Found in The Life, speeches, and public services of Abraham Lincoln: together with a sketch of the life of Hannibal Hamlin: Republican candidates for the offices of President and Vice-President of the United States (1860), Rudd & Carleton, p. 50-51.

- Lincoln was alluding to the words of Jesus in Luke 15:7

Speech at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

- Online text Speech at Peoria, Illinois, in Reply to Senator Douglas (16 October 1854); published in The Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln (1894) Vol. 2

- The foregoing history may not be precisely accurate in every particular; but I am sure it is sufficiently so, for all the uses I shall attempt to make of it, and in it, we have before us, the chief material enabling us to correctly judge whether the repeal of the Missouri Compromise is right or wrong.

I think, and shall try to show, that it is wrong; wrong in its direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska—and wrong in its prospective principle, allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world, where men can be found inclined to take it.

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticising the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

- When Southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery than we are, I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists, and that it is very difficult to get rid of it in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself. If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land. But a moment's reflection would convince me that whatever of high hope (as I think there is) there may be in this in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition? I think I would not hold one in slavery at any rate, yet the point is not clear enough for me to denounce people upon. What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially our equals. My own feelings will not admit of this, and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of whites will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment is not the sole question, if indeed it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill founded, cannot be safely disregarded. We cannot then make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted, but for their tardiness in this I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the South.

- Wherever slavery is, it has been first introduced without law. The oldest laws we find concerning it, are not laws introducing it; but regulating it, as an already existing thing.

- The negative principle that no law is free law, is not much known except among lawyers.

- "Fools rush in where angels fear to tread." At the hazard of being thought one of the fools of this quotation, I meet that argument — I rush in — I take that bull by the horns. I trust I understand and truly estimate the right of self-government. My faith in the proposition that each man should do precisely as he pleases with all which is exclusively his own lies at the foundation of the sense of justice there is in me. I extend the principle to communities of men as well as to individuals. I so extend it because it is politically wise, as well as naturally just: politically wise in saving us from broils about matters which do not concern us. Here, or at Washington, I would not trouble myself with the oyster laws of Virginia, or the cranberry laws of Indiana. The doctrine of self-government is right, — absolutely and eternally right, — but it has no just application as here attempted. Or perhaps I should rather say that whether it has such application depends upon whether a negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, in that case he who is a man may as a matter of self-government do just what he pleases with him.

But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent a total destruction of self-government to say that he too shall not govern himself. When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself and also governs another man, that is more than self-government — that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that "all men are created equal," and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man's making a slave of another.

- Judge Douglas frequently, with bitter irony and sarcasm, paraphrases our argument by saying: "The white people of Nebraska are good enough to govern themselves, but they are not good enough to govern a few miserable negroes!"

Well! I doubt not that the people of Nebraska are and will continue to be as good as the average of people elsewhere. I do not say the contrary. What I do say is that no man is good enough to govern another man without that other's consent. I say this is the leading principle, the sheet-anchor of American republicanism. Our Declaration of Independence says: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

I have quoted so much at this time merely to show that, according to our ancient faith, the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed. Now the relation of master and slave is pro tanto a total violation of this principle. The master not only governs the slave without his consent, but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes for himself. Allow ALL the governed an equal voice in the government, and that, and that only, is self-government.

- I insist, that if there is ANY THING which it is the duty of the WHOLE PEOPLE to never entrust to any hands but their own, that thing is the preservation and perpetuity, of their own liberties, and institutions.

- Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man's nature — opposition to it, in his love of justice. These principles are an eternal antagonism; and when brought into collision so fiercely, as slavery extension brings them, shocks, and throes, and convulsions must ceaselessly follow. Repeal the Missouri Compromise — repeal all compromises — repeal the Declaration of Independence — repeal all past history, you still can not repeal human nature. It still will be the abundance of man's heart, that slavery extension is wrong; and out of the abundance of his heart, his mouth will continue to speak.

- Stand with anybody that stands RIGHT. Stand with him while he is right and PART with him when he goes wrong.

- Little by little, but steadily as man's march to the grave, we have been giving up the OLD for the NEW faith. Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a “sacred right of self-government.” These principles can not stand together. They are as opposite as God and mammon; and whoever holds to the one, must despise the other. [...] Let no one be deceived. The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms; and the former is being rapidly displaced by the latter.

- Already the liberal party throughout the world, express the apprehension “that the one retrograde institution in America, is undermining the principles of progress, and fatally violating the noblest political system the world ever saw.” This is not the taunt of enemies, but the warning of friends. Is it quite safe to disregard it—to despise it? Is there no danger to liberty itself, in discarding the earliest practice, and first precept of our ancient faith? In our greedy chase to make profit of the negro, let us beware, lest we “cancel and tear to pieces” even the white man's charter of freedom.

- Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust. Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution. Let us turn slavery from its claims of “moral right,” back upon its existing legal rights, and its arguments of 'necessity'. Let us return it to the position our fathers gave it; and there let it rest in peace. Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it. Let north and south—let all Americans—let all lovers of liberty everywhere—join in the great and good work. If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union; but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving. We shall have so saved it, that the succeeding millions of free happy people, the world over, shall rise up, and call us blessed, to the latest generations.

- In the course of my main argument, Judge Douglas interrupted me to say, that the principle the Nebraska bill was very old; that it originated when God made man and placed good and evil before him, allowing him to choose for himself, being responsible for the choice he should make. At the time I thought this was merely playful; and I answered it accordingly. But in his reply to me he renewed it, as a serious argument. In seriousness then, the facts of this proposition are not true as stated. God did not place good and evil before man, telling him to make his choice. On the contrary, he did tell him there was one tree, of the fruit of which, he should not eat, upon pain of certain death.

Speech on the Dred Scott Decision (1857)

- We believe … in obedience to, and respect for the judicial department of government. We think its decisions on Constitutional questions, when fully settled, should control, not only the particular cases decided, but the general policy of the country, subject to be disturbed only by amendments of the Constitution as provided in that instrument itself. More than this would be revolution. But we think the Dred Scott decision is erroneous. … If this important decision had been made by the unanimous concurrence of the judges, and without any apparent partisan bias, and in accordance with legal public expectation, and with the steady practice of the departments throughout our history, and had been in no part, based on assumed historical facts which are not really true; or, if wanting in some of these, it had been before the court more than once, and had there been affirmed and re-affirmed through a course of years, it then might be, perhaps would be, factious, nay, even revolutionary, to not acquiesce in it as a precedent.

- Chief Justice does not directly assert, but plainly assumes, as a fact, that the public estimate of the black man is more favorable now than it was in the days of the Revolution. … In those days, as I understand, masters could, at their own pleasure, emancipate their slaves; but since then, such legal restraints have been made upon emancipation, as to amount almost to prohibition. In those days, Legislatures held the unquestioned power to abolish slavery in their respective States; but now it is becoming quite fashionable for State Constitutions to withhold that power from the Legislatures. In those days, by common consent, the spread of the black man's bondage to new countries was prohibited; but now, Congress decides that it will not continue the prohibition, and the Supreme Court decides that it could not if it would. In those days, our Declaration of Independence was held sacred by all, and thought to include all; but now, to aid in making the bondage of the negro universal and eternal, it is assailed, and sneered at, and construed, and hawked at, and torn, till, if its framers could rise from their graves, they could not at all recognize it. All the powers of earth seem rapidly combining against him. Mammon is after him; ambition follows, and philosophy follows, and the Theology of the day is fast joining the cry. They have him in his prison house; they have searched his person, and left no prying instrument with him. One after another they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him, and now they have him, as it were, bolted in with a lock of a hundred keys, which can never be unlocked without the concurrence of every key; the keys in the hands of a hundred different men, and they scattered to a hundred different and distant places; and they stand musing as to what invention, in all the dominions of mind and matter, can be produced to make the impossibility of his escape more complete than it is. It is grossly incorrect to say or assume, that the public estimate of the negro is more favorable now than it was at the origin of the government.

- There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people, to the idea of an indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races; and Judge Douglas evidently is basing his chief hope, upon the chances of being able to appropriate the benefit of this disgust to himself. If he can, by much drumming and repeating, fasten the odium of that idea upon his adversaries, he thinks he can struggle through the storm. He therefore clings to this hope, as a drowning man to the last plank. He makes an occasion for lugging it in from the opposition to the Dred Scott decision. He finds the Republicans insisting that the Declaration of Independence includes ALL men, black as well as white; and forth-with he boldly denies that it includes negroes at all, and proceeds to argue gravely that all who contend it does, do so only because they want to vote, and eat, and sleep, and marry with negroes! He will have it that they cannot be consistent else. Now I protest against that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. I need not have her for either, I can just leave her alone. In some respects she certainly is not my equal; but in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of any one else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.

- I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal-equal in "certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This they said, and this meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, nor yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit. They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere. The assertion that "all men are created equal" was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain; and it was placed in the Declaration, nor for that, but for future use. Its authors meant it to be, thank God, it is now proving itself, a stumbling block to those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism. They knew the proneness of prosperity to breed tyrants, and they meant when such should re-appear in this fair land and commence their vocation they should find left for them at least one hard nut to crack. I have now briefly expressed my view of the meaning and objects of that part of the Declaration of Independence which declares that "all men are created equal".

- Will springs from the two elements of moral sense and self-interest.

- The Republicans inculcate, with whatever of ability they can, that the negro is a man; that his bondage is cruelly wrong, and that the field of his oppression ought not to be enlarged. The Democrats deny his manhood; deny, or dwarf to insignificance, the wrong of his bondage; so far as possible, crush all sympathy for him, and cultivate and excite hatred and disgust against him; compliment themselves as Union-savers for doing so; and call the indefinite outspreading of his bondage "a sacred right of self-government".

The House Divided speech (1858)

- Speech at the Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois, accepting the Republican nomination for US Senate (16 June 1858)

- If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed.

- "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.

- In this famous statement Lincoln is quoting the response of Jesus Christ to those who accused him of being able to cast out devils because he was empowered by the Prince of devils, recorded in Matthew 12:25: "And Jesus knew their thoughts, and said unto them, Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation; and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand".

- Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.

Have we no tendency to the latter condition?

Let any one who doubts, carefully contemplate that now almost complete legal combination — piece of machinery so to speak — compounded of the Nebraska doctrine, and the Dred Scott decision.

- The new year of 1854 found slavery excluded from more than half the States by State constitutions, and from most of the national territory by congressional prohibition. Four days later commenced the struggle which ended in repealing that congressional prohibition. This opened all the national territory to slavery, and was the first point gained. But, so far, Congress only had acted; and an indorsement by the people, real or apparent, was indispensable to save the point already gained and give chance for more. This necessity had not been overlooked; but had been provided for, as well as might be, in the notable argument of "squatter sovereignty," otherwise called "sacred right of self government," which latter phrase, though expressive of the only rightful basis of any government, was so perverted in this attempted use of it as to amount to just this: That if any one man, choose to enslave another, no third man shall be allowed to object.

- Under the Dred Scott decision, "squatter sovereignty" squatted out of existence, tumbled down like temporary scaffolding — like the mould at the foundry served through one blast and fell back into loose sand — helped to carry an election, and then was kicked to the winds.

- The several points of the Dred Scott decision, in connection with Senator Douglas's "care-not" policy, constitute the piece of machinery, in its present state of advancement. This was the third point gained. The working points of that machinery are: (1) That no negro slave, imported as such from Africa, and no descendant of such slave, can ever be a citizen of any State, in the sense of that term as used in the Constitution of the United States. This point is made in order to deprive the negro in every possible event of the benefit of that provision of the United States Constitution which declares that "the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States." (2) That, "subject to the Constitution of the United States," neither Congress nor a territorial legislature can exclude slavery from any United States Territory. This point is made in order that individual men may fill up the Territories with slaves, without danger of losing them as property, and thus enhance the chances of permanency to the institution through all the future. (3) That whether the holding a negro in actual slavery in a free State makes him free as against the holder, the United States courts will not decide, but will leave to be decided by the courts of any slave State the negro may be forced into by the master. This point is made not to be pressed immediately, but, if acquiesced in for a while, and apparently indorsed by the people at an election, then to sustain the logical conclusion that what Dred Scott's master might lawfully do with Dred Scott in the free State of Illinois, every other master may lawfully do with any other one or one thousand slaves in Illinois or in any other free State.

- Auxiliary to all this, and working hand in hand with it, the Nebraska doctrine, or what is left of it, is to educate and mold public opinion, at least Northern public opinion, not to care whether slavery is voted down or voted up. This shows exactly where we now are; and partially, also, whither we are tending.

It will throw additional light on the latter, to go back, and run the mind over the string of historical facts already stated. Several things will now appear less dark and mysterious than they did when they were transpiring. The people were to be left "perfectly free," subject only to the Constitution. What the Constitution had to do with it, outsiders could not then see. Plainly enough now, it was an exactly fitted niche, for the Dred Scott decision to afterward come in, and declare the perfect free freedom of the people to be just no freedom at all. Why was the amendment, expressly declaring the right of the people, voted down? Plainly enough now: the adoption of it would have spoiled the niche for the Dred Scott decision.

- We cannot absolutely know that all these exact adaptations are the result of preconcert. But when we see a lot of framed timbers, different portions of which we know have been gotten out at different times and places, and by different workmen — Stephen, Franklin, Roger, and James, for instance — and when we see these timbers joined together, and see they exactly matte the frame of a house or a mill, all the tenons and mortices exactly fitting, and all the lengths and proportions of the different pieces exactly adapted to their respective places, and not a piece too many or too few, — not omitting even scaffolding — or, if a single piece be lacking, we see the place in the frame exactly fitted and prepared yet to bring such piece in — in such a case we find it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and James all understood one another from the beginning and all worked upon a common plan or draft drawn up before the first blow was struck.

- While the opinion of the court, by Chief-Justice Taney, in the Dred Scott case and the separate opinions of all the concurring judges, expressly declare that the Constitution of the United States neither permits Congress nor a Territorial legislature to exclude slavery from any United States Territory, they all omit to declare whether or not the same Constitution permits a State, or the people of a State, to exclude it.

- Such a decision is all that slavery now lacks of being alike lawful in all the States. Welcome, or unwelcome, such decision is probably coming, and will soon be upon us, unless the power of the present political dynasty shall be met and overthrown. We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free, and we shall awake to the reality instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State. To meet and overthrow the power of that dynasty is the work now before all those who would prevent that consummation. This is what we have to do. How can we best do it?

- There are those who denounce us openly to their own friends and yet whisper us softly, that Senator Douglas is the aptest instrument there is with which to effect that object. They wish us to infer all this from the fact that he now has a little quarrel with the present head of the dynasty; and that he has regularly voted with us on a single point upon which he and we have never differed. They remind us that he is a great man, and that the largest of us are very small ones. Let this be granted. But "a living dog is better than a dead lion." Judge Douglas, if not a dead lion, for this work, is at least a caged and toothless one. How can he oppose the advances of slavery? He does not care anything about it. His avowed mission is impressing the "public heart" to care nothing about it. A leading Douglas Democratic newspaper thinks Douglas's superior talent will be needed to resist the revival of the African slave-trade. Does Douglas believe an effort to revive that trade is approaching? He has not said so. Does he really think so? But if it is, how can he resist it? For years he has labored to prove it a sacred right of white men to take negro slaves into the new Territories. Can he possibly show that it is less a sacred right to buy them where they can be bought cheapest? And unquestionably they can be bought cheaper in Africa than in Virginia. He has done all in his power to reduce the whole question of slavery to one of a mere right of property; and as such, how can he oppose the foreign slave trade — how can he refuse that trade in that "property" shall be "perfectly free" — unless he does it as a protection to the home production? And as the home producers will probably not ask the protection, he will be wholly without a ground of opposition.

- Senator Douglas holds, we know, that a man may rightfully be wiser today than he was yesterday — that he may rightfully change when he finds himself wrong. But can we, for that reason, run ahead, and infer that he will make any particular change, of which he, himself, has given no intimation?

- Now, as ever, I wish not to misrepresent Judge Douglas's position, question his motives, or do aught that can be personally offensive to him. Whenever, if ever, he and we can come together on principle so that our cause may have assistance from his great ability, I hope to have interposed no adventitious obstacle. But clearly, he is not now with us — he does not pretend to be — he does not promise ever to be. Our cause, then, must be intrusted to, and conducted by, its own undoubted friends — those whose hands are free, whose hearts are in the work — who do care for the result.

- Of strange, discordant, and even hostile elements, we gathered from the four winds, and formed and fought the battle through, under the constant hot fire of a disciplined, proud, and pampered enemy. Did we brave all them to falter now? — now, when that same enemy is wavering, dissevered, and belligerent? The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail — if we stand firm, we shall not fail. Wise counsels may accelerate, or mistakes delay it, but, sooner or later, the victory is sure to come.

Speech at Chicago (1858)

- We are now a mighty nation, we are thirty—or about thirty millions of people, and we own and inhabit about one‑fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty‑two years and we discover that we were then a very small people in point of numbers, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a vastly less extent of country, with vastly less of everything we deem desirable among men, we look upon the change as exceedingly advantageous to us and to our posterity, and we fix upon something that happened away back, as in some way or other being connected with this rise of prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men, they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity that we now enjoy has come to us. We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves—we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better men in the age, and race, and country in which we live for these celebrations. But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole.