Doris Lessing

Appearance

Doris Lessing (22 October 1919 – 17 November 2013) was a British writer, born Doris May Tayler. In October 2007, Lessing became the eleventh woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in its 106-year history, and its oldest ever recipient.

- See also: Canopus in Argos

Quotes

[edit]1950–1999

[edit]

- It is terrible to destroy a person's picture of himself in the interests of truth or some other abstraction.

- The Grass Is Singing, ch. 2 (1950)

- The three men looked at the murderer, thinking their own thoughts, speculative, frowning, but not as if he were important now. No, he was unimportant: he was the constant, the black man who will thieve, rape, murder, if given half a chance. ... "I work hard enough, don't I? All day I am down on the lands with these lazy black savages, fighting them to get some work out of them. ... Above all, she hated the way they suckled their babies, with their breasts hanging down for everyone to see; there was something in their calm satisfied maternity that made her blood boil. "Their babies hanging on them like leeches," she said to herself shuddering, for she thought with horror of suckling a child. The idea of a child's lips on her breasts made her feel quite sick; at the thought of it she would involuntarily clasp her hands over her breasts, as if protecting them from a violation. And since so many white women are like her, turning with relief to the bottle, she was in good company, and did not think of herself, but rather of these black women, as strange; they were alien and primitive creatures with ugly desires she could not bear to think about. ... the touch of this black man's hand on her shoulder filled her with nausea; she had never, not once in her whole life, touched the flesh of a native.

- The Grass Is Singing (1950).

- Setting: Southern Rhodesia (British colony), now Zimbabwe. Author nationality: British. First published: UK and USA.

- In university they don't tell you that the greater part of the law is learning to tolerate fools.

- Martha Quest (1952), Part III, ch. 2

- If a fish is the movement of water embodied, given shape, then cat is a diagram and pattern of subtle air.

- Particularly Cats, ch. 2 (1967)

- That is what learning is. You suddenly understand something you've understood all your life, but in a new way.

- The Four-Gated City (1969)

- Nonsense, it was all nonsense: this whole damned outfit, with its committees, its conferences, its eternal talk, talk, talk, was a great con trick; it was a mechanism to earn a few hundred men and women incredible sums of money.

- The Summer Before the Dark (1973)

- You know, whenever women make imaginary female kingdoms in literature, they are always very permissive, to use the jargon word, and easy and generous and self-indulgent, like the relationships between women when there are no men around. They make each other presents, and they have little feasts, and nobody punishes anyone else. This is the female way of going along when there are no men about or when men are not in the ascendant.

- quoted in "A Talk With Doris Lessing; Lessing Author's Query" (30 March 1980), Minda Bikman, The New York Times Book Review

- There are certain types of people who are political out of a kind of religious reason [...] I think it's fairly common among socialists: They are, in fact, God-seekers, looking for the kingdom of God on earth. A lot of religious reformers have been like that, too. It's the same psychological set, trying to abolish the present in favor of some better future — always taking it for granted that there is a better future. If you don't believe in heaven, then you believe in socialism. When I was in my real Communist phase, I and the people around me really believed — but, of course, this makes us certifiable — that something like 10 years after World War II, the world would be Communist and perfect.

- quoted in Lesley Hazelton "Doris Lessing on Feminism, Communism and Space Fiction", The New York Times Book Review (25 July 1982)

- It can be considered a rule that the probable duration of an Empire may be prognosticated by the degree to which its rulers believe in their own propaganda.

- The Sentimental Agents in the Volyen Empire (1983), p. 94, Flamingo edition

- In the writing process, the more the story cooks, the better. The brain works for you even when you are at rest. I find dreams particularly useful. I myself think a great deal before I go to sleep and the details sometimes unfold in the dream.

- Interview with Herbert Mitgang, "Mrs. Lessing Addresses Some of Life's Puzzles", The New York Times, (22 April 1984)

- You can only learn to be a better writer by actually writing. I don't know much about creative writing programs. But they're not telling the truth if they don't teach, one, that writing is hard work and, two, that you have to give up a great deal of life, your personal life, to be a writer.

- Interview with Herbert Mitgang, "Mrs. Lessing Addresses Some of Life's Puzzles," The New York Times (22 April 1984)

- This world is run by people who know how to do things. They know how things work. They are equipped. Up there, there's a layer of people who run everything. But we — we're just peasants. We don't understand what's going on, and we can't do anything.

- The Good Terrorist (1985)

- There are no laws for the novel. There never have been, nor can there ever be.

- As quoted in Writers on Writing (1986) by Jon Winokur

- Space or science fiction has become a dialect for our time.

- The Guardian, London (7 November 1988)

- All one's life as a young woman one is on show, a focus of attention, people notice you. You set yourself up to be noticed and admired. And then, not expecting it, you become middle-aged and anonymous. No one notices you. You achieve a wonderful freedom. It's a positive thing. You can move about unnoticed and invisible.

- As quoted in An Uncommon Scold (1989) by Abby Adams, p. 18

- The great secret that all old people share is that you really haven't changed in seventy or eighty years. Your body changes, but you don't change at all. And that, of course, causes great confusion.

- The Sunday Times (London, 10 May 1992)

- Political correctness is the natural continuum from the party line. What we are seeing once again is a self-appointed group of vigilantes imposing their views on others. It is a heritage of communism, but they don't seem to see this.

- The Sunday Times (London, 10 May 1992)

- Does political correctness have a good side? Yes, it does, for it makes us re-examine attitudes, and that is always useful. The trouble is that, as with all popular movements, the lunatic fringe so quickly ceases to be a fringe; the tail begins to wag the dog. For every woman or man who is quietly and sensibly using the idea to look carefully at our assumptions, there are twenty rabble-rousers whose real motive is a desire for power over others. The fact that they see themselves as antiracists or feminists or whatever does not make them any less rabble-rousers.

- "Unexamined Mental Attitudes Left Behind By Communism", in Our Country, Our Culture - The Politics of Political Correctness (1994), Partisan Review Press, edited by Edith Kurzweil and William Philips

- What they [critics of Lessing's switch to science fiction] didn't realize was that in science fiction is some of the best social fiction of our time.

- Boston Book Review interview by Harvey Blume (February 1998)

- With a library you are free, not confined by temporary political climates. It is the most democratic of institutions because no one — but no one at all — can tell you what to read and when and how.

- Index on Censorship (March/April 1999)

The Golden Notebook (1962)

[edit]

- My major aim was to shape a book which would make its own comment, a wordless statement: to talk through the way it was shaped.

As I have said, this was not noticed- Introduction (1971 edition)

- I think it possible that Marxism was the first attempt, for our time, outside the formal religions, at a world-mind, a world-ethic. It went wrong, could not prevent itself from dividing and subdividing, like all the other religions, into smaller and smaller chapels, sects, and creeds. But it was an attempt.

- Introduction (1971)

- Ideally, what should be said to every child, repeatedly, throughout his or her school life is something like this:

"You are in the process of being indoctrinated. We have not yet evolved a system of education that is not a system of indoctrination. We are sorry, but it is the best we can do. What you are being taught here is an amalgam of current prejudice and the choices of this particular culture. The slightest look at history will show how impermanent these must be. You are being taught by people who have been able to accommodate themselves to a regime of thought laid down by their predecessors. It is a self-perpetuating system. Those of you who are more robust and individual than others will be encouraged to leave and find ways of educating yourself — educating your own judgements. Those that stay must remember, always, and all the time, that they are being moulded and patterned to fit into the narrow and particular needs of this particular society."- Introduction (1971)

- There is only one way to read, which is to browse in libraries and bookshops, picking up books that attract you, reading only those, dropping them when they bore you, skipping the parts that drag — and never, never reading anything because you feel you ought, or because it is part of a trend or a movement. Remember that the book which bores you when you are twenty or thirty will open doors for you when you are forty or fifty — and vice versa. Don’t read a book out of its right time for you.

- Introduction (1971)

- The two women were alone in the London flat.

"The point is," said Anna, as her friend came back from the telephone on the landing, "the point is, that as far as I can see, everything's cracking up."- First lines, "Free Women: 1"

- The point is, that the function of the novel seems to be changing; it has become an outpost of journalism; we read novels for information about areas of life we don’t know — Nigeria, South Africa, the American army, a coal-mining village, coteries in Chelsea, etc. We read to find out what is going on. One novel in five hundred or a thousand has the quality a novel should have to make it a novel — the quality of philosophy.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 1"

- The novel has become a function of the fragmented society, the fragmented consciousness. Human beings are so divided, are becoming more and more divided, and more subdivided in themselves, reflecting the world, that they reach out desperately, not knowing they do it, for information about other groups inside their own country, let alone about groups in other countries. It is a blind grasping out for their own wholeness, and the novel-report is a means toward it.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 1"

- What is so painful about that time is that nothing was disastrous. It was all wrong, ugly, unhappy and coloured with cynicism, but nothing was tragic, there were no moments that could change anything or anybody. From time to time the emotional lightning flashed and showed a landscape of private misery, and then — we went on dancing.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 1"

- We spend our lives fighting to get people very slightly more stupid than ourselves to accept truths that the great men have always known. They have known for thousands of years that to lock a sick person into solitary confinement makes him worse. They have known for thousands of years that a poor man who is frightened of his landlord and of the police is a slave. They have known it. We know it. But do the great enlightened mass of the British people know it? No. It is our task, Ella, yours and mine, to tell them. Because the great men are too great to be bothered. They are already discovering how to colonise Venus and to irrigate the moon. That is what is important for our time. You and I are the boulder-pushers. All our lives, you and I, we’ll put all our energies, all our talents into pushing a great boulder up a mountain. The boulder is the truth that the great men know by instinct, and the mountain is the stupidity of mankind.

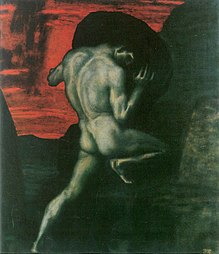

- Paul Tanner, in "Free Women: 1"

- Do you know what people really want? Everyone, I mean. Everybody in the world is thinking: I wish there was just one other person I could really talk to, who could really understand me, who'd be kind to me. That's what people really want, if they're telling the truth.

- It seems to me like this. It's not a terrible thing — I mean, it may be terrible, but it's not damaging, it's not poisoning, to do without something one really wants. It's not bad to say: My work is not what I really want, I'm capable of doing something bigger. Or I'm a person who needs love, and I'm doing without it. What's terrible is to pretend that the second-rate is the first-rate. To pretend that you don't need love when you do; or you like your work when you know quite well you're capable of better.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 2"

- It isn’t only the terror everywhere, and the fear of being conscious of it, that freezes people. It’s more than that. People know they are in a society dead or dying. They are refusing emotion because at the end of very emotion are property, money, power. They work and despise their work, and so freeze themselves. They love but know that it’s a half- love or a twisted love, and so they freeze themselves.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 4"

- There was a kind of shifting of the balances of my brain, of the way I had been thinking, the same kind of realignment as when, a few days before, words like democracy, liberty, freedom, had faded under pressure of a new sort of understanding of the real movement of the world towards dark, hardening power. I knew, but of course the word, written, cannot convey the quality of this knowing, that whatever already is has its logic and its force. I felt this, like a vision, in a new kind of knowing. And I knew that the cruelty and the spite and the I.I.I.I. of Saul and of Anna were part of the logic of war; and I knew how strong these emotions were, in a way that would never leave me, would become part of how I saw the world.

- Anna Wulf, in "Free Women: 4"

- I knew, and it was an illumination — one of those things one has always known, but never understood before — that all sanity depends on this: that it should be a delight to feel the roughness of a carpet under smooth soles, a delight to feel heat strike the skin, a delight to stand upright, knowing the bones are moving easily under flesh. If this goes, then the conviction of life goes too. But I could feel none of this. … I knew I was moving into a new dimension, further from sanity than I had ever been.

- Anna Wulf, in "The Golden Notebook"

- You want me to begin a novel with The two women were alone in the London flat?

- Anna Wulf, in "The Golden Notebook"

- Sometimes I pick up a book and I say: Well, so you've written it first, have you? Good for you. O.K., then I won't have to write it.

- Saul Green in "The Golden Notebook"

- There's only one real sin, and that is to persuade oneself that the second-best is anything but the second-best.

- Anna Wulf

- None of you ask for anything — except everything, but just for so long as you need it.

- Anna Wulf

- Literature is analysis after the event.

- The Golden Notebook. Bantam Books. 1979. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-553-13675-3. Quoted in Children of Albion: Poetry of the Underground in Britain, ed. Michael Horovitz (1969): Afterwords, section 2

Salon interview (1997)

[edit]

- The automatic reaction of practically any young person is, at once, against authority. That, I think, began in the First World War because of the trenches, and the incompetence of the people on all fronts. I think that a terrible bitterness and anger began there, which led to communism. And now it feeds terrorism. Anyway, that's my thesis. It's very oversimplified, as you can see.

- It was OK, us being Reds during the war, because we were all on the same side. But then the Cold War started. Almost overnight we became enemies of people who were close friends — they crossed the street to avoid us.

- Why were the Europeans bothered about the Soviet Union at all? It was nothing to do with us. China had nothing to do with us. Why were we not building, without reference to the Soviet Union, a good society in our own countries? But no, we were all — in one way or another — obsessed with the bloody Soviet Union, which was a disaster. What people were supporting was failure. And continually justifying it.

- I'm always astounded at the way we automatically look at what divides and separates us. We never look at what people have in common. If you see it, black and white people, both sides look to see the differences, they don't look at what they have together. Men and women, and old and young, and so on. And this is a disease of the mind, the way I see it. Because in actual fact, men and women have much more in common than they are separated.

- All political movements are like this — we are in the right, everyone else is in the wrong. The people on our own side who disagree with us are heretics, and they start becoming enemies. With it comes an absolute conviction of your own moral superiority. There's oversimplification in everything, and a terror of flexibility.

- The current publishing scene is extremely good for the big, popular books. They sell them brilliantly, market them and all that. It is not good for the little books. And really valuable books have been allowed to go out of print. In the old days, the publishers knew that these difficult books, the books that appeal only to a minority, were very productive in the long run. Because they're probably the books that will be read in the next generation. It's heart-breaking how often I have to say when I'm giving talks, "This book is out of print. This book is out of print." It's a roll call of dead books.

2001–2013

[edit]- [On her first marriage ] I don't think marriages are like that now. It's when you walk into a role. The life was all laid down, what you ate, everything you did, and I went through it all as if it were a role in a play, really, and I hated it bitterly.

- I have to face the fact that I and my high-minded comrades, both those in that chimerical Communist Party in Southern Rhodesia, and many I have met since ... were of the stuff of those murderers with a clear conscience. We were lucky, that's all.

- "Doris Lessing: An unusual feminist", The Independent (18 August 2001)

- In the words of interviewer Natasha Walter (before the first quote): "Lessing's escape from her family led her into another trap, marriage to a civil servant at the age of 19." She severed her links to the Communist Party in 1956.

- What matters most is that we learn from living.

- As quoted in Permission to Play : Taking Time to Renew Your Smile (2003) by Jill Murphy Long, p. 147

- Parents should leave books lying around marked "forbidden" if they want their children to read.

- Interview with Amanda Craig, "Grand dame of letters who's not going quietly", The Times (London, 23 November 2003, reprinted 3 June 2004)

- Any human anywhere will blossom in a hundred unexpected talents and capacities simply by being given the opportunity to do so.

- As quoted in Wisdom for the Soul: Five Millennia of Prescriptions for Spiritual Healing (2006) by Larry Chang, p. 660

- I do not think writers ought ever to sit down and think they must write about some cause, or theme... If they write about their own experiences, something true is going to emerge.

- "Literature Nobel Awarded to Writer Doris Lessing" All Things Considered NPR (11 October 2007)

- This has been going on for 30 years. I've won all the prizes in Europe, every bloody one, so I'm delighted to win them all. It's a royal flush.

- After being chosen as the 2007 recipient of the Nobel Prize For Literature "BBC News", BBC, London (11 October 2007)

- Oh Christ. I couldn't care less. … I can't say I'm overwhelmed with surprise. I'm 88 years old and they can't give the Nobel to someone who's dead, so I think they were probably thinking they'd probably better give it to me now before I've popped off.

- The Golden Notebook for some reason surprised people but it was no more than you would hear women say in their kitchens every day in any country. … I was really astounded that some people were shocked.

- As quoted in an undated profile at the BBC World Service

- I was taken around and shown things as a "useful idiot" […] that’s what my role was […] I can’t understand why I was so gullible.

- Concerning her 1952 trip to the USSR.

- Interview, excerpted in part 1 of Useful Idiots - BBC World Service (7 July 2010) at about 2:30. Part 1 on iTunes. Original page at archive.org.

Misattributed

[edit]- What is a hero without love for mankind?

- Was ist ein Held ohne Menschenliebe!

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Philotas (1759), Act 1, Scene 7

- It is the mark of great people to treat trifles as trifles and important matters as important.

- Denn zu einem großen Manne gehört beides: Kleinigkeiten als Kleinigkeiten, und wichtige Dinge als wichtige Dinge zu behandeln.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Hamburgische Dramaturgie (1767 - 1769), Vierunddreißigstes Stück Den 25. August 1767

- Pearls mean tears.

- Perlen bedeuten Tränen.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Emilia Galotti (1772), Act II, scene VIII

- Better Counsel comes overnight.

- Besserer Rat kommt über Nacht.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Emilia Galotti (1772), Act IV, scene III

- I, who ne'er

Went for myself a begging, go a borrowing,

And that for others. Borrowing's much the same

As begging; just as lending upon usury

Is much the same as thieving.

- The worst of superstitions is to think

One's own most bearable.- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise (1779), Act IV, scene II

- Variant translation: The worst superstition is to consider our own tolerable.

- Think wrongly, if you please, but in all cases think for yourself.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, as quoted in The London Medical Gazette Vol. V (1847), p. 1118; and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing: His Life and His Works (1878) by Helen Zimmern, p. 443 In "Grand dame of letters who's not going quietly", The Times (London, 23 November 2003), the phrase is unattributed, but interviewer Amanda Craig says it is Doris Lessing's own "motto".

- Borrowing is not much better than begging; just as lending with interest is not much better than stealing.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, as quoted in Dictionary of Quotations from Ancient and Modern English and Foreign Sources (1893) by James Wood, p. 32

- Man, whence is he? / Too bad to be the work of a god, too good for the work of chance.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, as quoted in Dictionary of Quotations from Ancient and Modern English and Foreign Sources (1899) by James Wood, p. 61; usually attributed to Doris Lessing in the form: "Man — who is he? Too bad, to be the work of God: Too good for the work of chance!"

- Trust no friend without faults, and love a maiden, but no angel.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, as quoted in Dictionary of Quotations from Ancient and Modern English and Foreign Sources (1899) by James Wood, p. 499

- For the last third of life there remains only work. It alone is always stimulating, rejuvenating, exciting and satisfying.

- Käthe Kollwitz, diary entry (1 January 1912)

- I have found it to be true that the older I've become the better my life has become.

- Rush Limbaugh, as quoted in Old Age Is Always 15 Years Older Than I Am (2001) by Randy Voorhees

Quotes about Lessing

[edit]- I have read a lot of Doris Lessing, and her interrogation of human behavior and history always makes a big impression on me.

- Leila Aboulela Interview with World Literature Today (2019)

- Doris Lessing, The Grass is Singing and the Children of Violence series. That again was actually a very positive influence upon me. I particularly liked her writing in the Children of Violence series: so down-to-earth and real! It made me think that this is the material that I have. It just relates to ordinary people that live ordinary lives, but, if Doris Lessing thinks it's important enough to record and the world agrees with her, then maybe I can use that same kind of material as well to make the points that I think should be made.

- Tsitsi Dangarembga in Talking with African Writers by Jane Wilkinson

- Doris Lessing—always searching, always on her way to something new and different, what a range of intelligence, her every book a blow at artistic complacency. The Golden Notebook I consider her masterpiece.

- 1979 interview in Conversations with Nadine Gordimer edited by Nancy Topping Bazin and Marilyn Dallman Seymour (1990)

- When was reviewing Doris Lessing's last two books from the Shikasta series, I found that she has discovered what I, to my great joy, had discovered a little earlier: that (a) if you're writing what they call science fiction, you're absolutely free-you can write anything you damn please, and (b) that if you take seriously the science fiction premise, you are furnished with an inexhaustable supply of absolutely beautiful and complex metaphors for our present situation, for who and where we are now, and I think it's not only women who have found this out. Angus Wilson was one of the first to do this with The Old Man in the Zoo years ago. That is a science fiction novel, if you look at it closely. Several of the writers who interest me most are doing this sort of thing, but Lessing has done it wholeheartedly and courageously. I love her introduction that says academics put science fiction down and to hell with them! That's really nice coming from Doris Lessing.

- 1980 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2002)

- I sure like Doris Lessing.

- 1981 interview in Conversations with Grace Paley (1997)

- She might well wonder what took them so long. Doris Lessing is the ideal winner of the Nobel Prize. After all, the prize is about idealism, and was founded in the belief that writers can make the world a better place.

Lessing can depict the world as a terrible place, peopled by terrorists, in which the women can be as violent as the men, and war can describe the planet entirely.

But she never abandons the hope that the planet can be better, even if she has to imagine other planets to show how this is possible.

- The assumption made by Rossi, that women are "innately" sexually oriented only toward men, and that made by Lessing, that the lesbian is simply acting out of her bitterness toward men, are by no means theirs alone; these assumptions are widely current in literature and in the social sciences.

- Adrienne Rich, Blood, Bread, and Poetry (1986)

- Doris Lessing's heroine, who has felt devoured by her own mother, splits herself-or tries to-when she realizes she, too, is to become a mother.

- Adrienne Rich Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (1976)

- I also can’t get along with Turgenev, though I love Russians, or Doris Lessing, though I am a feminist.

- Zadie Smith Interview (2016)

- Doris Lessing was nothing less than the goddess of literature herself for young women like myself aspiring to write in the 1970s. Her classic, The Golden Notebook, directly addressed the contradictions in women's lives in a way that was sophisticated, insightful and dispassionate.... When I started writing novels in the early 1980s, I often felt pressure from women to depict wholesome female role models. The pressure never worked, partly because Doris Lessing had gone before and blazed a path for all of us as readers, as women, as people.

- Mrs. Lessing's view of recent politics is not everyone's. Her view of the future (inevitably brutish and painful) is that it is the present: that we are all hypnotized, awaiting cataclysms which we are in fact living through now; that we are now — as we run and read — in the process of a rapid evolution; that we are mutating fast but can't see it, the chief characteristic of our race being its inability to see what is under its nose; that historians and scientists, in their timid traditionalism, feed our fantasy view of ourselves — suppressing truths about the human condition, about madness, about sanity, about the essential nature of the mind.

External links

[edit]Categories:

- Novelists from England

- Essayists from England

- Short story writers from England

- Playwrights from England

- Poets from England

- Science fiction authors from England

- Autobiographers from England

- Left communists

- Sufis

- 1919 births

- 2013 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Nobel laureates from England

- Socialists from England

- Women from England

- Women authors

- Women born in the 1910s

- People who are first to

- Deaths from disease

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Women Nobel laureates