Essays (Francis Bacon)

Appearance

Essayes or Counsels, Civill and Morall (1625) by Francis Bacon is a book of essays that cover topics drawn from both public and private life, and in each case the essays cover their topics systematically from a number of different angles, weighing one argument against another.

Quotes

[edit]

- I do now publish my Essays, which, of all my other works, have been most current; for that, as it seems, they come home to men's business and bosoms. I have enlarged them both in number and weight; so that they are indeed a new work.

- Dedication to the Essays (edition 1625)

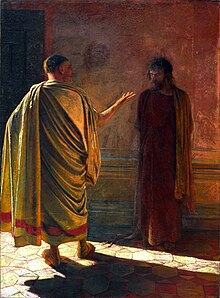

Of Truth

[edit]- What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.

- No pleasure is comparable to the standing upon the vantage-ground of truth.

- Truth is a naked and open daylight, that doth not shew the masks and mummeries and triumphs of the world, half so stately and daintily as candlelights.

- It is not the lie that passeth through the mind, but the lie that sinketh in and settleth in it, that doth the hurt.

- Certainly, it is heaven upon earth, to have a man's mind move in charity, rest in providence, and turn upon the poles of truth.

- There is no vice that doth so cover a man with shame as to be found false and perfidious. And therefore Montaigne saith prettily, when he inquired the reason, why the word of the lie should be such a disgrace, and such an odious charge? Saith he, If it be well weighed, to say that a man lieth, is as much to say, as that he is brave towards God, and a coward towards men. For a lie faces God, and shrinks from man. Surely the wickedness of falsehood, and breach of faith, cannot possibly be so highly expressed, as in that it shall be the last peal, to call the judgments of God upon the generations of men; it being foretold, that when Christ cometh, he shall not find faith upon the earth.

Of Death

[edit]- Men fear death, as children fear to go in the dark; and as that natural fear in children, is increased with tales, so is the other.

- Certainly, the contemplation of death, as the wages of sin, and passage to another world, is holy and religious; but the fear of it, as a tribute due unto nature, is weak. Yet in religious meditations, there is sometimes mixture of vanity, and of superstition.

- It is as natural to die, as to be born; and to a little infant, perhaps, the one is as painful, as the other.

- He that dies in an earnest pursuit, is like one that is wounded in hot blood; who, for the time, scarce feels the hurt; and therefore a mind fixed, and bent upon somewhat that is good, doth avert the dolors of death.

- But, above all, believe it, the sweetest canticle is', Nunc dimittis; when a man hath obtained worthy ends, and expectations. Death hath this also; that it openeth the gate to good fame, and extinguisheth envy.—Extinctus amabitur idem.

Of Unity In Religion

[edit]- Men fear death as children fear to go in the dark; and as that natural fear in children is increased with tales, so is the other.

- It is worthy the observing, that there is no passion in the mind of man, so weak, but it mates, and masters, the fear of death; and therefore, death is no such terrible enemy, when a man hath so many attendants about him, that can win the combat of him. Revenge triumphs over death; love slights it; honor aspireth to it; grief flieth to it; fear preoccupieth it.

- Certain Laodiceans, and lukewarm persons, think they may accommodate points of religion, by middle way, and taking part of both, and witty reconcilements; as if they would make an arbitrament between God and man. Both these extremes are to be avoided; which will be done, if the league of Christians, penned by our Savior himself, were in two cross clauses thereof, soundly and plainly expounded: He that is not with us, is against us; and again, He that is not against us, is with us; that is, if the points fundamental and of substance in religion, were truly discerned and distinguished, from points not merely of faith, but of opinion, order, or good intention.

Of Revenge

[edit]- Revenge is a kind of wild justice; which the more man's nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out.

- Some, when they take revenge, are desirous, the party should know, whence it cometh. This is the more generous. For the delight seemeth to be, not so much in doing the hurt, as in making the party repent.

- But base and crafty cowards, are like the arrow that flieth in the dark.

- This is certain, that a man that studieth revenge, keeps his own wounds green, which otherwise would heal, and do well.

- Vindictive persons live the life of witches; who, as they are mischievous, so end they infortunate...

- Certainly, in taking revenge, a man is but even with his enemy; but in passing it over, he is superior; for it is a prince's part to pardon.

Of Adversity

[edit]- It is yet a higher speech of his than the other, "It is true greatness to have in one the frailty of a man and the security of a god."

- It was a high speech of Seneca (after the manner of the Stoics), that "The good things which belong to prosperity are to be wished, but the good things that belong to adversity are to be admired."

- Prosperity is the blessing of the Old Testament; adversity is the blessing of the New.

- The virtue of prosperity, is temperance; the virtue of adversity, is fortitude; which in morals is the more heroical virtue. Prosperity is the blessing of the Old Testament; adversity is the blessing of the New; which carrieth the greater benediction, and the clearer revelation of God's favor. Yet even in the Old Testament, if you listen to David's harp, you shall hear as many hearse-like airs as carols; and the pencil of the Holy Ghost hath labored more in describing the afflictions of Job, than the felicities of Solomon. Prosperity is not without many fears and distastes; and adversity is not without comforts and hopes.

- Prosperity doth best discover vice, but adversity doth best discover virtue.

- Virtue is like precious odors — most fragrant when they are incensed or crushed.

Of Simulation And Dissimulation

[edit]- Dissimulations is but a faint kind of policy, or wisdom; for it asketh a strong wit, and a strong heart, to know when to tell truth, and to do it. Therefore it is the weaker sort of politics, that are the great dissemblers.

- Certainly the ablest men that ever were, have had all an openness, and frankness, of dealing; and a name of certainty and veracity; but then they were like horses well managed; for they could tell passing well, when to stop or turn; and at such times, when they thought the case indeed required dissimulation, if then they used it, it came to pass that the former opinion, spread abroad, of their good faith and clearness of dealing, made them almost invisible.

- In few words, mysteries are due to secrecy. Besides (to say truth) nakedness is uncomely, as well in mind as body; and it addeth no small reverence, to men's manners and actions, if they be not altogether open.

- As for talkers and futile persons, they are commonly vain and credulous withal. For he that talketh what he knoweth, will also talk what he knoweth not.

- It is a good shrewd proverb of the Spaniard, Tell a lie and find a truth.

Of Parents and Children

[edit]- The joys of parents are secret; and so are their griefs and fears. They cannot utter the one; nor they will not utter the other.

- Children sweeten labors; but they make misfortunes more bitter.

- They increase the cares of life; but they mitigate the remembrance of death.

- The perpetuity by generation is common to beasts; but memory, merit, and noble works, are proper to men. And surely a man shall see the noblest works and foundations have proceeded from childless men; which have sought to express the images of their minds, where those of their bodies have failed.

Of Marriage and Single Life

[edit]- He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises, either of virtue or mischief. Certainly the best works, and of greatest merit for the public, have proceeded from the unmarried or childless men; which both in affection and means, have married and endowed the public.

- Nay more, there are some foolish rich covetous men, that take a pride, in having no children, because they may be thought so much the richer. For perhaps they have heard some talk, Such an one is a great rich man, and another except to it, Yea, but he hath a great charge of children; as if it were an abatement to his riches. But the most ordinary cause of a single life, is liberty, especially in certain self-pleasing and humorous minds, which are so sensible of every restraint, as they will go near to think their girdles and garters, to be bonds and shackles.

- Unmarried men are best friends, best masters, best servants; but not always best subjects; for they are light to run away; and almost all fugitives, are of that condition.

- A single life doth well with churchmen; for charity will hardly water the ground, where it must first fill a pool. It is indifferent for judges and magistrates; for if they be facile and corrupt, you shall have a servant, five times worse than a wife.

- Certainly wife and children are a kind of discipline of humanity; and single men, though they may be many times more charitable, because their means are less exhaust, yet, on the other side, they are more cruel and hardhearted (good to make severe inquisitors), because their tenderness is not so oft called upon.

- Chaste women are often proud and froward, as presuming upon the merit of their chastity. It is one of the best bonds, both of chastity and obedience, in the wife, if she think her husband wise; which she will never do, if she find him jealous.

- Wives are young men's mistresses; companions for middle age; and old men's nurses.

- But yet he was reputed one of the wise men, that made answer to the question, when a man should marry,—A young man not yet, an elder man not at all.

- It is often seen that bad husbands, have very good wives; whether it be, that it raiseth the price of their husband's kindness, when it comes; or that the wives take a pride in their patience.

Of Envy

[edit]- A man that hath no virtue in himself, ever envieth virtue in others. For men's minds, will either feed upon their own good, or upon others' evil; and who wanteth the one, will prey upon the other; and whoso is out of hope, to attain to another's virtue, will seek to come at even hand, by depressing another's fortune.

- Neither can he, that mindeth but his own business, find much matter for envy. For envy is a gadding passion, and walketh the streets, and doth not keep home: Non est curiosus, quin idem sit malevolus.

- Men of noble birth, are noted to be envious towards new men, when they rise. For the distance is altered, and it is like a deceit of the eye, that when others come on, they think themselves, go back.

- Deformed persons, and eunuchs, and old men, and bastards, are envious. For he that cannot possibly mend his own case, will do what he can, to impair another's; except these defects light upon a very brave, and heroical nature, which thinketh to make his natural wants part of his honor; in that it should be said, that an eunuch, or a lame man, did such great matters; affecting the honor of a miracle; as it was in Narses the eunuch, and Agesilaus and Tamberlanes, that were lame men.

- The same is the case of men, that rise after calamities and misfortunes. For they are as men fallen out with the times; and think other men's harms, a redemption of their own sufferings.

- They that desire to excel in too many matters, out of levity and vain glory, are ever envious. For they cannot want work; it being impossible, but many, in some one of those things, should surpass them. Which was the character of Adrian the Emperor; that mortally envied poets, and painters, and artificers, in works wherein he had a vein to excel.

- Above all, those are most subject to envy, which carry the greatness of their fortunes, in an insolent and proud manner; being never well, but while they are showing how great they are, either by outward pomp, or by triumphing over all opposition or competition; whereas wise men will rather do sacrifice to envy, in suffering themselves sometimes of purpose to be crossed, and overborne in things that do not much concern them.

- We will add this in general, touching the affection of envy; that of all other affections, it is the most importune and continual. For of other affections, there is occasion given, but now and then; and therefore it was well said, Invidia festos dies non agit: for it is ever working upon some or other.

Of Love

[edit]- For there was never proud man thought so absurdly well of himself, as the lover doth of the person loved; and therefore it was well said, That it is impossible to love, and to be wise.

- For it is a true rule, that love is ever rewarded either with the reciproque, or with an inward and secret contempt.

- Nuptial love maketh mankind, friendly love perfecteth it, but wonton love corrupteth and embaseth it.

Of Great Place

[edit]- Men in great place are thrice servants,—servants of the sovereign or state, servants of fame, and servants of business.

- It is an assured sign of a worthy and generous spirit, whom honor amends. For honor is, or should be, the place of virtue and as in nature, things move violently to their place, and calmly in their place, so virtue in ambition is violent, in authority settled and calm. All rising to great place is by a winding stair; and if there be factions, it is good to side a man's self, whilst he is in the rising, and to balance himself when he is placed.

- Use the memory of thy predecessor, fairly and tenderly; for if thou dost not, it is a debt will sure be paid when thou art gone. If thou have colleagues, respect them, and rather call them, when they look not for it, than exclude them, when they have reason to look to be called. Be not too sensible, or too remembering, of thy place in conversation, and private answers to suitors; but let it rather be said, When he sits in place, he is another man.

- It is a strange desire, to seek power and to lose liberty.

Of Boldness

[edit]- Mahomet made the people believe that he would call a hill to him, and from the top of it offer up his prayers for the observers of his law. The people assembled. Mahomet called the hill to come to him, again and again; and when the hill stood still he was never a whit abashed, but said, "If the hill will not come to Mahomet, Mahomet will go to the hill."

- There is in human nature generally more of the fool than of the wise; and therefore, those faculties by which the foolish part of men's minds is taken are most potent. Wonderful like is the case of boldness in civil business. What first?—Boldness: what second and third?—Boldness. And yet boldness is a child of ignorance and baseness, far inferior to other parts; but, nevertheless, it doth fascinate, and bind hand and foot those that are either shallow in judgment or weak in courage, which are the greatest part, yea, and prevaileth with wise man at weak times.

- Boldness is ever blind; for it seeth not dangers and inconveniences. Therefore it is ill in counsel, good in execution; so that the right use of bold persons is, that they never command in chief, but be seconds, and under the direction of others. For in counsel, it is good to see dangers; and in execution, not to see them, except they be very great.

Of Goodness and Goodness of Nature

[edit]- I take goodness in this sense, the affecting of the weal of men, which is that the Grecians call philanthropia; and the word humanity (as it is used) is a little too light to express it. Goodness I call the habit, and goodness of nature, the inclination. This of all virtues, and dignities of the mind, is the greatest; being the character of the Deity: and without it, man is a busy, mischievous, wretched thing; no better than a kind of vermin.

- In charity there is no excess.

- If a man be gracious and courteous to strangers, it shows he is a citizen of the world, and that his heart is no island cut off from other lands, but a continent that joins to them.

- The desire of power in excess caused the angels to fall; the desire of knowledge in excess caused man to fall.

Of Nobility

[edit]- A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny... A great and potent nobility, addeth majesty to a monarch, but diminisheth power; and putteth life and spirit into the people, but presseth their fortune. It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings.

- As for nobility in particular persons; it is a reverend thing, to see an ancient castle or building, not in decay; or to see a fair timber tree, sound and perfect. How much more, to behold an ancient noble family, which has stood against the waves and weathers of time! For new nobility is but the act of power, but ancient nobility is the act of time. Those that are first raised to nobility, are commonly more virtuous, but less innocent, than their descendants

- Nobility of birth commonly abateth industry; and he that is not industrious, envieth him that is. Besides, noble persons cannot go much higher; and he that standeth at a stay, when others rise, can hardly avoid motions of envy. On the other side, nobility extinguisheth the passive envy from others, towards them; because they are in possession of honor. Certainly, kings that have able men of their nobility, shall find ease in employing them, and a better slide into their business; for people naturally bend to them, as born in some sort to command.

Of Seditions and Troubles

[edit]- Concerning the materials of seditions. It is a thing well to be considered; for the surest way to prevent seditions (if the times do bear it) is to take away the matter of them. For if there be fuel prepared, it is hard to tell, whence the spark shall come, that shall set it on fire. The matter of seditions is of two kinds: much poverty, and much discontentment. It is certain, so many overthrown estates, so many votes for troubles. Lucan noteth well the state of Rome before the Civil War: Hinc usura vorax, rapidumque in tempore foenus, Hinc concussa fides, et multis utile bellum.

- The causes and motives of seditions are, innovation in religion; taxes; alteration of laws and customs; breaking of privileges; general oppression; advancement of unworthy persons; strangers; dearths; disbanded soldiers; factions grown desperate; and what soever, in offending people, joineth and knitteth them in a common cause.

- For the remedies; there may be some general preservatives, whereof we will speak: as for the just cure, it must answer to the particular disease; and so be left to counsel, rather than rule. The first remedy or prevention is to remove, by all means possible, that material cause of sedition whereof we spake; which is, want and poverty in the estate. To which purpose serveth the opening, and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufactures; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste, and excess, by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulating of prices of things vendible; the moderating of taxes and tributes; and the like.

- Above all things, good policy is to be used, that the treasure and moneys, in a state, be not gathered into few hands. For otherwise a state may have a great stock, and yet starve. And money is like muck, not good except it be spread. This is done, chiefly by suppressing, or at least keeping a strait hand, upon the devouring trades of usury, ingrossing great pasturages, and the like.

- Neither let any prince, or state, be secure concerning discontentments, because they have been often, or have been long, and yet no peril hath ensued: for as it is true, that every vapor or fume doth not turn into a storm; so it is nevertheless true, that storms, though they blow over divers times, yet may fall at last; and, as the Spanish proverb noteth well, The cord breaketh at the last by the weakest pull.

- The remedy is worse than the disease.

Of Atheism

[edit]- I had rather believe all the fables in the legends and the Talmud and the Alcoran, than that this universal frame is without a mind.

- And therefore, God never wrought miracle, to convince atheism, because his ordinary works convince it. A little philosophy inclineth man's mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men's minds about to religion. (In the original archaic English this read: I HAD rather beleeve all the Fables in the Legend, and the Talmud, and the Alcoran, then that this universall Frame, is without a Minde. And therefore, God never wrought Miracle, to convince Atheisme, because his Ordinary Works convince it. It is true, that a little Philosophy inclineth Mans Minde to Atheisme; But depth in Philosophy, bringeth Mens Mindes about to Religion.)

- The Scripture saith, The fool hath said in his heart, there is no God; it is not said, The fool hath thought in his heart; so as he rather saith it, by rote to himself, as that he would have, than that he can thoroughly believe it, or be persuaded of it. For none deny, there is a God, but those, for whom it maketh that there were no God. It appeareth in nothing more, that atheism is rather in the lip, than in the heart of man, than by this; that atheists will ever be talking of that their opinion, as if they fainted in it, within themselves, and would be glad to be strengthened, by the consent of others.

- You shall have atheists strive to get disciples, as it fareth with other sects. And, which is most of all, you shall have of them, that will suffer for atheism, and not recant; whereas if they did truly think, that there were no such thing as God, why should they trouble themselves?

- The great atheists, indeed are hypocrites; which are ever handling holy things, but without feeling; so as they must needs be cauterized in the end.

- They that deny a God destroy a man's nobility, for certainly man is of kin to the beasts by his body; and if he be not of kin to God by his spirit, he is a base and ignoble creature.

- Therefore, as atheism is in all respects hateful, so in this, that it depriveth human nature of the means to exalt itself, above human frailty.

Of Superstition

[edit]- It were better to have no opinion of God at all, than such an opinion, as is unworthy of him. For the one is unbelief, the other is contumely; and certainly superstition is the reproach of the Deity.

- The causes of superstition are: pleasing and sensual rites and ceremonies; excess of outward and pharisaical holiness; overgreat reverence of traditions, which cannot but load the church; the stratagems of prelates, for their own ambition and lucre; the favoring too much of good intentions, which openeth the gate to conceits and novelties; the taking an aim at divine matters, by human, which cannot but breed mixture of imaginations: and, lastly, barbarous times, especially joined with calamities and disasters.

- Superstition, without a veil, is a deformed thing; for, as it addeth deformity to an ape, to be so like a man, so the similitude of superstition to religion, makes it the more deformed. And as wholesome meat corrupteth to little worms, so good forms and orders corrupt, into a number of petty observances.

- There is a superstition in avoiding superstition, when men think to do best, if they go furthest from the superstition, formerly received; therefore care would be had that (as it fareth in ill purgings) the good be not taken away with the bad; which commonly is done, when the people is the reformer.

Of Travel

[edit]- Travel, in the younger sort, is a part of education; in the elder, a part of experience. He that traveleth into a country before he hath some entrance into the language, goeth to school, and not to travel.

- If you will have a young man to put his travel into a little room, and in short time to gather much, this you must do. First, as was said, he must have some entrance into the language before he goeth. Then he must have such a servant, or tutor, as knoweth the country, as was likewise said. Let him carry with him also, some card or book, describing the country where he travelleth; which will be a good key to his inquiry. Let him keep also a diary.

- Let him not stay long, in one city or town; more or less as the place deserveth, but not long; nay, when he stayeth in one city or town, let him change his lodging from one end and part of the town, to another; which is a great adamant of acquaintance. Let him sequester himself, from the company of his countrymen, and diet in such places, where there is good company of the nation where he travelleth.

- Let him, upon his removes from one place to another, procure recommendation to some person of quality, residing in the place whither he removeth; that he may use his favor, in those things he desireth to see or know. Thus he may abridge his travel, with much profit.

- As for the acquaintance, which is to be sought in travel; that which is most of all profitable, is acquaintance with the secretaries and employed men of ambassadors: for so in travelling in one country, he shall suck the experience of many. Let him also see, and visit, eminent persons in all kinds, which are of great name abroad; that he may be able to tell, how the life agreeth with the fame.

- And let a man beware, how he keepeth company with choleric and quarrelsome persons; for they will engage him into their own quarrels.

- When a traveller returneth home, let him not leave the countries, where he hath travelled, altogether behind him; but maintain a correspondence by letters, with those of his acquaintance, which are of most worth. And let his travel appear rather in his discourse, than his apparel or gesture

Of Empire

[edit]- It is a miserable state of mind, to have few things to desire, and many things to fear; and yet that commonly is the case of kings; who, being at the highest, want matter of desire, which makes their minds more languishing; and have many representations of perils and shadows, which makes their minds the less clear.

- Princes many times make themselves desires, and set their hearts upon toys; sometimes upon a building; sometimes upon erecting of an order; sometimes upon the advancing of a person; sometimes upon obtaining excellency in some art, or feat of the hand; as Nero for playing on the harp, Domitian for certainty of the hand with the arrow, Commodus for playing at fence, Caracalla for driving chariots, and the like.

- The mind of man, is more cheered and refreshed by profiting in small things, than by standing at a stay, in great. We see also that kings that have been fortunate conquerors, in their first years, it being not possible for them to go forward infinitely, but that they must have some check, or arrest in their fortunes, turn in their latter years to be superstitious, and melancholy; as did Alexander the Great; Diocletian; and in our memory, Charles the Fifth; and others: for he that is used to go forward, and findeth a stop, falleth out of his own favor, and is not the thing he was.

- To speak now of the true temper of empire, it is a thing rare and hard to keep; for both temper, and distemper, consist of contraries. But it is one thing, to mingle contraries, another to interchange them. The answer of Apollonius to Vespasian, is full of excellent instruction. Vespasian asked him, What was Nero's overthrow? He answered, Nero could touch and tune the harp well; but in government, sometimes he used to wind the pins too high, sometimes to let them down too low. And certain it is, that nothing destroyeth authority so much, as the unequal and untimely interchange of power pressed too far, and relaxed too much.

- The difficulties in princes' business are many and great; but the greatest difficulty, is often in their own mind.

- Kings have to deal with their neighbors, their wives, their children, their prelates or clergy, their nobles, their second-nobles or gentlemen, their merchants, their commons, and their men of war; and from all these arise dangers, if care and circumspection be not used.

- For their nobles; to keep them at a distance, it is not amiss; but to depress them, may make a king more absolute, but less safe; and less able to perform, any thing that he desires. I have noted it, in my History of King Henry the Seventh of England, who depressed his nobility; whereupon it came to pass, that his times were full of difficulties and troubles; for the nobility, though they continued loyal unto him, yet did they not co-operate with him in his business. So that in effect, he was fain to do all things himself.

- Princes are like to heavenly bodies, which cause good or evil times; and which have much veneration, but no rest. All precepts concerning kings, are in effect comprehended in those two remembrances: memento quod es homo; and memento quod es Deus, or vice Dei; the one bridleth their power, and the other their will.

Of Counsel

[edit]- The greatest trust, between man and man, is the trust of giving counsel. For in other confidences, men commit the parts of life; their lands, their goods, their children, their credit, some particular affair; but to such as they make their counsellors, they commit the whole: by how much the more, they are obliged to all faith and integrity.

- The counsels at this day, in most places, are but familiar meetings, where matters are rather talked on, than debated. And they run too swift, to the order, or act, of counsel. It were better that in causes of weight, the matter were propounded one day, and not spoken to till the next day; in nocte consilium. So was it done in the Commission of Union, between England and Scotland; which was a grave and orderly assembly.

- I commend set days for petitions; for both it gives the suitors more certainty for their attendance, and it frees the meetings for matters of estate, that they may hoc agere. In choice of committees; for ripening business for the counsel, it is better to choose indifferent persons, than to make an indifferency, by putting in those, that are strong on both sides.

- A king, when he presides in counsel, let him beware how he opens his own inclination too much, in that which he propoundeth; for else counsellors will but take the wind of him, and instead of giving free counsel, sing him a song of placebo.

Of Delays

[edit]- Fortune is like the market, where many times, if you can stay a little, the price will fall.

Of Cunning

[edit]- We take cunning for a sinister or crooked wisdom. And certainly there is a great difference, between a cunning man, and a wise man; not only in point of honesty, but in point of ability. There be, that can pack the cards, and yet cannot play well; so there are some that are good in canvasses and factions, that are otherwise weak men.

- Again, it is one thing to understand persons, and another thing to understand matters; for many are perfect in men's humors, that are not greatly capable of the real part of business; which is the constitution of one that hath studied men, more than books. Such men are fitter for practice, than for counsel; and they are good, but in their own alley: turn them to new men, and they have lost their aim; so as the old rule, to know a fool from a wise man, Mitte ambos nudos ad ignotos, et videbis, doth scarce hold for them. And because these cunning men, are like haberdashers of small wares, it is not amiss to set forth their shop.

- It is a point of cunning, to wait upon him with whom you speak, with your eye; as the Jesuits give it in precept: for there be many wise men, that have secret hearts, and transparent countenances. Yet this would be done with a demure abasing of your eye, sometimes, as the Jesuits also do use.

- Nothing doth more hurt in a state than that cunning men pass for wise.

- In things that a man would not be seen in himself, it is a point of cunning to borrow the name of the world; as to say, "The world says," or "There is a speech abroad."

- There is a cunning which we in England call "the turning of the cat in the pan;" which is, when that which a man says to another, he lays it as if another had said it to him.

- It is a good point of cunning for a man to shape the answer he would have in his own words and propositions, for it makes the other party stick the less.

- Be true to thyself, as thou be not false to others.

Of Wisdom for a Man's Self

[edit]- It is the nature of extreme self-lovers, as they will set an house on fire, and it were but to roast their eggs.

Of Innovations

[edit]- As the births of living creatures at first are ill-shapen, so are all Innovations, which are the births of time.

- He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils; for time is the greatest innovator.

- It is good also, not to try experiments in states, except the necessity be urgent, or the utility evident; and well to beware, that it be the reformation, that draweth on the change, and not the desire of change, that pretendeth the reformation.

Of Dispatch

[edit]- Affected dispatch is one of the most dangerous things to business that can be. It is like that, which the physicians call predigestion, or hasty digestion; which is sure to fill the body full of crudities, and secret seeds of diseases. Therefore measure not dispatch, by the times of sitting, but by the advancement of the business.

Of Seeming Wise

[edit]- Seeming wise men may make shift to get opinion; but let no man choose them for employment; for certainly you were better take for business, a man somewhat absurd, than over-formal.

- It hath been an opinion that the French are wiser than they seem, and the Spaniards seem wiser than they are; but howsoever it be between nations, certainly it is so between man and man.

Of Friendship

[edit]- A crowd is not company; and faces are but a gallery of pictures; and talk but a tinkling cymbal, where there is no love.

- But we may go further, and affirm most truly, that it is a mere and miserable solitude to want true friends; without which the world is but a wilderness; and even in this sense also of solitude, whosoever in the frame of his nature and affections, is unfit for friendship, he taketh it of the beast, and not from humanity.

- Cure the disease and kill the patient.

Of Expense

[edit]- Riches are for spending, and spending for honor and good actions.

- A man had need, if he be plentiful in some kind of expense, to be as saving again in some other. As if he be plentiful in diet, to be saving in apparel; if he be plentiful in the hall, to be saving in the stable; and the like. For he that is plentiful in expenses of all kinds, will hardly be preserved from decay.

- In clearing of a man's estate, he may as well hurt himself in being too sudden, as in letting it run on too long. For hasty selling, is commonly as disadvantageable as interest. Besides, he that clears at once will relapse; for finding himself out of straits, he will revert to his custom: but he that cleareth by degrees, induceth a habit of frugality, and gaineth as well upon his mind, as upon his estate.

Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates

[edit]- He that commands the sea is at great liberty, and may take as much and as little of the war as he will.

Less than a span.

- The greatness of an estate, in bulk and territory, doth fall under measure; and the greatness of finances and revenue, doth fall under computation. The population may appear by musters; and the number and greatness of cities and towns by cards and maps. But yet there is not any thing amongst civil affairs more subject to error, than the right valuation and true judgment concerning the power and forces of an estate.

Of Regimen of Health

[edit]- There is a wisdom in this beyond the rules of physic. A man's own observation, what he finds good of and what he finds hurt of, is the best physic to preserve health.

- Beware of sudden change, in any great point of diet, and, if necessity inforce it, fit the rest to it. For it is a secret both in nature and state, that it is safer to change many things, than one.

- As for the passions and studies of the mind: avoid envy; anxious fears; anger fretting inwards; subtle and knotty inquisitions; joys and exhilarations in excess; sadness not communicated. Entertain hopes; mirth rather than joy; variety of delights, rather than surfeit of them; wonder and admiration, and therefore novelties; studies that fill the mind with splendid and illustrious objects, as histories, fables, and contemplations of nature.

Of Suspicion

[edit]- Suspicions amongst thoughts, are like bats amongst birds, they ever fly by twilight. Certainly they are to be repressed, or at least well guarded: for they cloud the mind; they leese friends; and they check with business, whereby business cannot go on currently and constantly. They dispose kings to tyranny, husbands to jealousy, wise men to irresolution and melancholy. They are defects, not in the heart, but in the brain; for they take place in the stoutest natures.

Of Discourse

[edit]- Some, in their discourse, desire rather commendation of wit, in being able to hold all arguments, than of judgment, in discerning what is true; as if it were a praise, to know what might be said, and not, what should be thought.

- Some have certain common places, and themes, wherein they are good and want variety; which kind of poverty is for the most part tedious, and when it is once perceived, ridiculous.

- The honorablest part of talk, is to give the occasion; and again to moderate, and pass to somewhat else; for then a man leads the dance. It is good, in discourse and speech of conversation, to vary and intermingle speech of the present occasion, with arguments, tales with reasons, asking of questions, with telling of opinions, and jest with earnest: for it is a dull thing to tire, and, as we say now, to jade, any thing too far.

- As for jest, there be certain things, which ought to be privileged from it; namely, religion, matters of state, great persons, any man's present business of importance, and any case that deserveth pity. Yet there be some, that think their wits have been asleep, except they dart out somewhat that is piquant, and to the quick.

- Intermingle...jest with earnest.

- Discretion of speech, is more than eloquence; and to speak agreeably to him, with whom we deal, is more than to speak in good words, or in good order.

Of Plantations

[edit]- Plantations are amongst ancient, primitive, and heroical works. When the world was young, it begat more children; but now it is old, it begets fewer: for I may justly account new plantations, to be the children of former kingdoms. I like a plantation in a pure soil; that is, where people are not displanted, to the end, to plant in others. For else it is rather an extirpation, than a plantation.

- If you plant where savages are, do not only entertain them, with trifles and gingles, but use them justly and graciously, with sufficient guard nevertheless; and do not win their favor, by helping them to invade their enemies, but for their defence it is not amiss; and send oft of them, over to the country that plants, that they may see a better condition than their own, and commend it when they return.

- When the plantation grows to strength, then it is time to plant with women, as well as with men; that the plantation may spread into generations, and not be ever pieced from without. It is the sinfullest thing in the world, to forsake or destitute a plantation once in forwardness; for besides the dishonor, it is the guiltiness of blood of many commiserable persons.

Of Riches

[edit]- I cannot call riches better than the baggage of virtue. The Roman word is better, impedimenta. For as the baggage is to an army, so is riches to virtue. It cannot be spared, nor left behind, but it hindereth the march; yea, and the care of it, sometimes loseth or disturbeth the victory.

- Of great riches there is no real use, except it be in the distribution; the rest is but conceit. So saith Solomon, Where much is, there are many to consume it; and what hath the owner, but the sight of it with his eyes? The personal fruition in any man, cannot reach to feel great riches: there is a custody of them; or a power of dole, and donative of them; or a fame of them; but no solid use to the owner.

- The gains of ordinary trades and vocations are honest; and furthered by two things chiefly: by diligence, and by a good name, for good and fair dealing. But the gains of bargains, are of a more doubtful nature; when men shall wait upon others' necessity, broke by servants and instruments to draw them on, put off others cunningly, that would be better chapmen, and the like practices, which are crafty and naught. As for the chopping of bargains, when a man buys not to hold but to sell over again, that commonly grindeth double, both upon the seller, and upon the buyer. Sharings do greatly enrich, if the hands be well chosen, that are trusted. Usury is the certainest means of gain, though one of the worst; as that whereby a man doth eat his bread, in sudore vultus alieni; and besides, doth plough upon Sundays.

Of Prophecies

[edit]- I mean not to speak of divine prophecies; nor of heathen oracles; nor of natural predictions; but only of prophecies that have been of certain memory, and from hidden causes. Saith the Pythonissa to Saul, To-morrow thou and thy son shall be with me... The daughter of Polycrates, dreamed that Jupiter bathed her father, and Apollo anointed him; and it came to pass, that he was crucified in an open place, where the sun made his body run with sweat, and the rain washed it.

Philip of Macedon dreamed, he sealed up his wife's belly; whereby he did expound it, that his wife should be barren; but Aristander the soothsayer, told him his wife was with child, because men do not use to seal vessels, that are empty.

- My judgment is, that they ought all to be despised; and ought to serve but for winter talk by the fireside. Though when I say despised, I mean it as for belief; for otherwise, the spreading, or publishing, of them, is in no sort to be despised. For they have done much mischief; and I see many severe laws made, to suppress them.

- Men mark when they hit, and never mark when they miss; as they do generally also of dreams.... probable conjectures, or obscure traditions, many times turn themselves into prophecies; while the nature of man, which coveteth divination, thinks it no peril to foretell that which indeed they do but collect... almost all of them, being infinite in number, have been impostures, and by idle and crafty brains merely contrived and feigned, after the event past.

Of Ambition

[edit]- So ambitious men, if they find the way open for their rising, and still get forward, they are rather busy than dangerous; but if they be checked in their desires, they become secretly discontent, and look upon men and matters with an evil eye, and are best pleased, when things go backward.

- Nature is often hidden; sometimes overcome; seldom extinguished.

Of Masks and Triumphs

[edit]- These things are but toys, to come amongst such serious observations.

- Let the suits of the masquers be graceful, and such as become the person, when the vizors are off; not after examples of known attires; Turke, soldiers, mariners', and the like. Let anti-masques not be long; they have been commonly of fools, satyrs, baboons, wild-men, antics, beasts, sprites, witches, Ethiops, pigmies, turquets, nymphs, rustics, Cupids, statuas moving, and the like. As for angels, it is not comical enough, to put them in anti-masques; and anything that is hideous, as devils, giants, is on the other side as unfit.

- For justs, and tourneys, and barriers; the glories of them are chiefly in the chariots, wherein the challengers make their entry; especially if they be drawn with strange beasts: as lions, bears, camels, and the like; or in the devices of their entrance; or in the bravery of their liveries; or in the goodly furniture of their horses and armor. But enough of these toys.

Of Nature in Men

[edit]- Nature is often hidden; sometimes overcome; seldom extinguished. Force, maketh nature more violent in the return; doctrine and discourse, maketh nature less importune; but custom only doth alter and subdue nature.

- He that seeketh victory over his nature, let him not set himself too great, nor too small tasks; for the first will make him dejected by often failings; and the second will make him a small proceeder, though by often prevailings.

- A man's nature is best perceived in privateness, for there is no affectation; in passion, for that putteth a man out of his precepts; and in a new case or experiment, for there custom leaveth him. They are happy men, whose natures sort with their vocations; otherwise they may say, multum incola fuit anima mea; when they converse in those things, they do not affect.

- In studies, whatsoever a man commandeth upon himself, let him set hours for it; but whatsoever is agreeable to his nature, let him take no care for any set times; for his thoughts will fly to it, of themselves; so as the spaces of other business, or studies, will suffice. A man's nature, runs either to herbs or weeds; therefore let him seasonably water the one, and destroy the other.

Of Custom and Education

[edit]- Men's thoughts, are much according to their inclination; their discourse and speeches, according to their learning and infused opinions; but their deeds, are after as they have been accustomed.

Of Fortune

[edit]- If a man look sharply and attentively, he shall see Fortune; for though she is blind, she is not invisible.

- Chiefly the mold of a man's fortune is in his own hands.

- If a man look sharply and attentively, he shall see Fortune; for though she is blind, she is not invisible.

Of Usury

[edit]- To speak now of the reformation, and reiglement, of usury; how the discommodities of it may be best avoided, and the commodities retained. It appears, by the balance of commodities and discommodities of usury, two things are to be reconciled. The one, that the tooth of usury be grinded, that it bite not too much; the other, that there be left open a means, to invite moneyed men to lend to the merchants, for the continuing and quickening of trade.

Of Youth and Age

[edit]- Young men are fitter to invent than to judge, fitter for execution than for counsel, and fitter for new projects than for settled business.

Of Beauty

[edit]- Virtue is like a rich stone — best plain set.

- There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion.

- Beauty is as summer fruits, which are easy to corrupt, and cannot last; and for the most part it makes a dissolute youth, and an age a little out of countenance; but yet certainly again, if it light well, it maketh virtue shine, and vices blush.

Of Deformity

[edit]- Deformed persons are commonly even with nature; for as nature hath done ill by them, so do they by nature; being for the most part (as the Scripture saith) void of natural affection; and so they have their revenge of nature.

Of Building

[edit]- Houses are built to live in, not to look on; therefore, let use be preferred before uniformity, except where both may be had.

Of Gardens

[edit]- God Almighty first planted a garden. And indeed it is the purest of human pleasures.

- And because the breath of flowers is far sweeter in the air (where it comes and goes, like the warbling of music) than in the hand, therefore nothing is more fit for that delight than to know what be the flowers and plants that do best perfume the air.

- The planting of hemp and flax would be an unknown advantage to the kingdom, many places therein being as apt for it , as any foreig parts.

Of Negotiating

[edit]- If you would work any man, you must either know his nature and fashions, and so lead him; or his ends, and so persuade him or his weakness and disadvantages, and so awe him or those that have interest in him, and so govern him. In dealing with cunning persons, we must ever consider their ends, to interpret their speeches; and it is good to say little to them, and that which they least look for.

- In all negotiations of difficulty, a man may not look to sow and reap at once; but must prepare business, and so ripen it by degrees.

Of Followers and Friends

[edit]- Costly followers are not to be liked; lest while a man maketh his train longer, he make his wings shorter.

Of Suitors

[edit]- Many ill matters and projects are undertaken; and private suits do putrefy the public good. Many good matters, are undertaken with bad minds; I mean not only corrupt minds, but crafty minds, that intend not performance. Some embrace suits, which never mean to deal effectually in them; but if they see there may be life in the matter, by some other mean, they will be content to win a thank, or take a second reward, or at least to make use, in the meantime, of the suitor's hopes. Some take hold of suits, only for an occasion to cross some other; or to make an information, whereof they could not otherwise have apt pretext; without care what become of the suit, when that turn is served; or, generally, to make other men's business a kind of entertainment, to bring in their own.

Of Studies

[edit]

- To spend too much time in studies is sloth; to use them too much for ornament, is affectation; to make judgment wholly by their rules, is the humor of a scholar. They perfect nature, and are perfected by experience: for natural abilities are like natural plants, that need proyning, by study; and studies themselves, do give forth directions too much at large, except they be bounded in by experience.

- Read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to find talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.

- Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested: that is, some books are to be read only in parts, others to be read, but not curiously, and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.

- Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.

Of Ceremonies and Respect

[edit]- Histories make men wise; poets, witty; the mathematics, subtile; natural philosophy, deep; moral, grave; logic and rhetoric, able to contend.

- A wise man will make more opportunities, than he finds.

Of Praise

[edit]- Certainly fame is like a river, that beareth up things light and swoln, and drowns things weighty and solid.

- A good name is like a precious ointment; it filleth all around about, and will not easily away; for the odors of ointments are more durable than those of flowers.

- Glorious men are the scorn of wise men, the admiration of fools, the idols of parasites, and the slaves of their own vaunts.

Of Vain-Glory

[edit]- So are there some vain persons, that whatsoever goeth alone, or moveth upon greater means, if they have never so little hand in it, they think it is they that carry it. They that are glorious, must needs be factious; for all bravery stands upon comparisons. They must needs be violent, to make good their own vaunts. Neither can they be secret, and therefore not effectual; but according to the French proverb, Beaucoup de bruit, peu de fruit; Much bruit little fruit.

- In fame of learning, the flight will be slow without some feathers of ostentation. Qui de contemnenda gloria libros scribunt, nomen, suum inscribunt. Socrates, Aristotle, Galen, were men full of ostentation. Certainly vain-glory helpeth to perpetuate a man's memory; and virtue was never so beholding to human nature, as it received his due at the second hand.

- In commending another, you do yourself right; for he that you commend, is either superior to you in that you commend, or inferior. If he be inferior, if he be to be commended, you much more; if he be superior, if he be not to be commended, you much less. Glorious men are the scorn of wise men, the admiration of fools, the idols of parasites, and the slaves of their own vaunts.

Of Honor and Reputation

[edit]- The winning of honor, is but the revealing of a man's virtue and worth, without disadvantage.n...

Of Judicature

[edit]- Judges ought to remember, that their office is jus dicere, and not jus dare; to interpret law, and not to make law, or give law. Else will it be like the authority, claimed by the Church of Rome, which under pretext of exposition of Scripture, doth not stick to add and alter; and to pronounce that which they do not find; and by show of antiquity, to introduce novelty.

- Judges ought to be more learned, than witty, more reverend, than plausible, and more advised, than confident. Above all things, integrity is their portion and proper virtue. Cursed (saith the law) is he that removeth the landmark. The mislayer of a mere-stone is to blame. But it is the unjust judge, that is the capital remover of landmarks, when he defineth amiss, of lands and property. One foul sentence doth more hurt, than many foul examples. For these do but corrupt the stream, the other corrupteth the fountain.

- The principal duty of a judge, is to suppress force and fraud; whereof force is the more pernicious, when it is open, and fraud, when it is close and disguised. Add thereto contentious suits, which ought to be spewed out, as the surfeit of courts.

- Judges must beware of hard constructions, and strained inferences; for there is no worse torture, than the torture of laws.

- In causes of life and death, judges ought (as far as the law permitteth) in justice to remember mercy; and to cast a severe eye upon the example, but a merciful eye upon the person.

- Patience and gravity of hearing, is an essential part of justice; and an overspeaking judge is no well-tuned cymbal. It is no grace to a judge, first to find that, which he might have heard in due time from the bar; or to show quickness of conceit, in cutting off evidence or counsel too short; or to prevent information by questions, though pertinent.

- The parts of a judge in hearing, are four: to direct the evidence; to moderate length, repetition, or impertinency of speech; to recapitulate, select, and collate the material points, of that which hath been said; and to give the rule or sentence.

- The place of justice is an hallowed place; and therefore not only the bench, but the foot-place; and precincts and purprise thereof, ought to be preserved without scandal and corruption.

- An ancient clerk, skilful in precedents, wary in proceeding, and understanding in the business of the court, is an excellent finger of a court; and doth many times point the way to the judge himself.

- Judges ought above all to remember the conclusion of the Roman Twelve Tables.

- Let not judges also be ignorant of their own right, as to think there is not left to them, as a principal part of their office, a wise use and application of laws.

Of Anger

[edit]- To seek to extinguish anger utterly, is but a bravery of the Stoics. We have better oracles:Be angry, but sin not. Let not the sun go down upon your anger.

Anger must be limited and confined, both in race and in time.

- We will first speak how the natural inclination and habit to be angry, may be attempted and calmed. Secondly, how the particular motions of anger may be repressed, or at least refrained from doing mischief. Thirdly, how to raise anger, or appease anger in another. For the first; there is no other way but to meditate, and ruminate well upon the effects of anger, how it troubles man's life. And the best time to do this, is to look back upon anger, when the fit is thoroughly over. Seneca saith well, That anger is like ruin, which breaks itself upon that it falls. The Scripture exhorteth us to possess our souls in patience. Whosoever is out of patience, is out of possession of his soul.

- Anger is certainly a kind of baseness; as it appears well in the weakness of those subjects in whom it reigns; children, women, old folks, sick folks. Only men must beware, that they carry their anger rather with scorn, than with fear; so that they may seem rather to be above the injury, than below it; which is a thing easily done, if a man will give law to himself in it.

- For the second point; the causes and motives of anger, are chiefly three. First, to be too sensible of hurt; for no man is angry, that feels not himself hurt; and therefore tender and delicate persons must needs be oft angry; they have so many things to trouble them, which more robust natures have little sense of. The next is, the apprehension and construction of the injury offered, to be, in the circumstances thereof, full of contempt: for contempt is that, which putteth an edge upon anger, as much or more than the hurt itself. And therefore, when men are ingenious in picking out circumstances of contempt, they do kindle their anger much. Lastly, opinion of the touch of a man's reputation, doth multiply and sharpen anger.

- To contain anger from mischief, though it take hold of a man, there be two things, whereof you must have special caution. The one, of extreme bitterness of words, especially if they be aculeate and proper; for cummunia maledicta are nothing so much; and again, that in anger a man reveal no secrets; for that, makes him not fit for society. The other, that you do not peremptorily break off, in any business, in a fit of anger; but howsoever you show bitterness, do not act anything, that is not revocable.

Of Vicissitude of Things

[edit]- The greatest vicissitude of things amongst men is the vicissitude of sects and religions.

Of Fame

[edit]- The poets make Fame a monster. They describe her in part finely and elegantly, and in part gravely and sententiously. They say, look how many feathers she hath, so many eyes she hath underneath; so many tongues; so many voices; she pricks up so many ears.

- She gathereth strength in going; that she goeth upon the ground, and yet hideth her head in the clouds; that in the daytime she sitteth in a watch tower, and flieth most by night; that she mingleth things done, with things not done; and that she is a terror to great cities.