Herman Melville

Appearance

Herman Melville (1 August 1819 – 28 September 1891) was an American novelist, essayist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period.

See also:

Quotes

[edit]

Audacity — reverence. These must mate,

And fuse with Jacob’s mystic heart,

To wrestle with the angel — Art.

- Dolt & ass that I am I have lived more than 29 years, & until a few days ago, never made close acquaintance with the divine William. Ah, he's full of sermons-on-the-mount, and gentle, aye, almost as Jesus. I take such men to be inspired. I fancy that this moment Shakspeare in heaven ranks with Gabriel, Raphael and Michael. And if another Messiah ever comes twill be in Shakesper's person. — I am mad to think how minute a cause has prevented me hitherto from reading Shakspeare. But until now, every copy that was come-atable to me, happened to be in a vile small print unendurable to my eyes which are tender as young sparrows. But chancing to fall in with this glorious edition, I now exult in it, page after page.

- Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (24 February 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 77

- I do not oscillate in Emerson's rainbow, but prefer rather to hang myself in mine own halter than swing in any other man's swing. Yet I think Emerson is more than a brilliant fellow. Be his stuff begged, borrowed, or stolen, or of his own domestic manufacture he is an uncommon man. Swear he is a humbug — then is he no common humbug. Lay it down that had not Sir Thomas Browne lived, Emerson would not have mystified — I will answer, that had not Old Zack's father begot him, old Zack would never have been the hero of Palo Alto. The truth is that we are all sons, grandsons, or nephews or great-nephews of those who go before us. No one is his own sire. — I was very agreeably disappointed in Mr Emerson. I had heard of him as full of transcendentalisms, myths & oracular gibberish; I had only glanced at a book of his once in Putnam's store — that was all I knew of him, till I heard him lecture. — To my surprise, I found him quite intelligible, tho' to say truth, they told me that that night he was unusually plain. — Now, there is a something about every man elevated above mediocrity, which is, for the most part, instinctuly perceptible. This I see in Mr Emerson. And, frankly, for the sake of the argument, let us call him a fool; — then had I rather be a fool than a wise man. — I love all men who dive. Any fish can swim near the surface, but it takes a great whale to go down stairs five miles or more; & if he don't attain the bottom, why, all the lead in Galena can't fashion the plumet that will. I'm not talking of Mr Emerson now — but of the whole corps of thought-divers, that have been diving & coming up again with bloodshot eyes since the world began.

I could readily see in Emerson, notwithstanding his merit, a gaping flaw. It was, the insinuation, that had he lived in those days when the world was made, he might have offered some valuable suggestions. These men are all cracked right across the brow. And never will the pullers-down be able to cope with the builders-up. And this pulling down is easy enough — a keg of powder blew up Block's Monument — but the man who applied the match, could not, alone, build such a pile to save his soul from the shark-maw of the Devil. But enough of this Plato who talks thro' his nose.- Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 78; a portion of this is sometimes modernized in two ways:

- Now, there is a something about every man elevated above mediocrity, which is for the most part instinctively perceptible.

- Now, there is a something about every man elevated above mediocrity, which is for the most part instantly perceptible.

- And do not think, my boy, that because I, impulsively broke forth in jubillations over Shakspeare, that, therefore, I am of the number of the snobs who burn their tuns of rancid fat at his shrine. No, I would stand afar off & alone, & burn some pure Palm oil, the product of some overtopping trunk. — I would to God Shakspeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway. Not that I might have had the pleasure of leaving my card for him at the Astor, or made merry with him over a bowl of the fine Duyckinck punch; but that the muzzle which all men wore on their soul in the Elizebethan day, might not have intercepted Shakspers full articulations. For I hold it a verity, that even Shakspeare, was not a frank man to the uttermost. And, indeed, who in this intolerant universe is, or can be? But the Declaration of Independence makes a difference.—There, I have driven my horse so hard that I have made my inn before sundown.

- Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 79

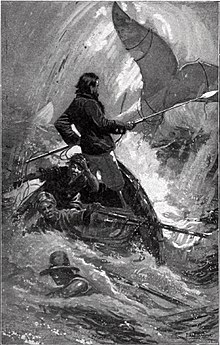

- It will be a strange sort of book, tho', I fear; blubber is blubber you know; tho' you may get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree; — & to cook the thing up, one must needs throw in a little fancy, which from the nature of the thing, must be ungainly as the gambols of the whales themselves. Yet I mean to give the truth of the thing, spite of this.

- On Moby-Dick, in a letter to Richard Henry Dana, Jr. (1 May 1850)

- There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne. We mean the tragedies of human thought in its own unbiassed, native, and profounder workings. We think that into no recorded mind has the intense feeling of the usable truth ever entered more deeply than into this man's. By usable truth, we mean the apprehension of the absolute condition of present things as they strike the eye of the man who fears them not, though they do their worst to him, — the man who, like Russia or the British Empire, declares himself a sovereign nature (in himself) amid the powers of heaven, hell, and earth. He may perish; but so long as he exists he insists upon treating with all Powers upon an equal basis. If any of those other Powers choose to withhold certain secrets, let them; that does not impair my sovereignty in myself; that does not make me tributary. And perhaps, after all, there is no secret. We incline to think that the Problem of the Universe is like the Freemason's mighty secret, so terrible to all children. It turns out, at last, to consist in a triangle, a mallet, and an apron, — nothing more! We incline to think that God cannot explain His own secrets, and that He would like a little information upon certain points Himself. We mortals astonish Him as much as He us. But it is this Being of the matter; there lies the knot with which we choke ourselves. As soon as you say Me, a God, a Nature, so soon you jump off from your stool and hang from the beam. Yes, that word is the hangman. Take God out of the dictionary, and you would have Him in the street.

There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie; and all men who say no,—why, they are in the happy condition of judicious, unincumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag, — that is to say, the Ego. Whereas those yes-gentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and, damn them ! they will never get through the Custom House. What's the reason, Mr. Hawthorne, that in the last stages of metaphysics a fellow always falls to swearing so? I could rip an hour.- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, including bits of a review of his work that he had written (c. 16 April 1851); published in Nathaniel Hawthorne and His WIfe Vol, I (1884) by Julian Hawthorne, Ch. VIII : Lenox, p. 388

- Not one man in five cycles, who is wise, will expect appreciative recognition from his fellows, or any one of them. Appreciation! Recognition! Is love appreciated? Why, ever since Adam, who has got to the meaning of this great allegory — the world? Then we pigmies must be content to have our paper allegories but ill comprehended.

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 157

- In me divine magnanimities are spontaneous and instantaneous — catch them while you can. The world goes round, and the other side comes up. So now I can't write what I felt. But I felt pantheistic then—your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God's. A sense of unspeakable security is in me this moment, on account of your having understood the book. I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb. Ineffable socialities are in me. I would sit down and dine with you and all the Gods in old Rome's Pantheon. It is a strange feeling — no hopelessness is in it, no despair. Content — that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 157

- Whence came you, Hawthorne? By what right do you drink from my flagon of life? And when I put it to my lips — lo, they are yours and not mine. I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces. Hence this infinite fraternity of feeling. Now, sympathising with the paper, my angel turns over another leaf. You did not care a penny for the book. But, now and then as you read, you understood the pervading thought that impelled the book — and that you praised. Was it not so? You were archangel enough to praise the imperfect body, and embrace the soul.

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 158

- The reason the mass of men fear God, and at bottom dislike Him, is because they rather distrust His heart, and fancy Him all brain like a watch. (You perceive I employ a capital initial in the pronoun referring to the Deity; don't you think there is a slight dash of flunkeyism in that usage?)

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (June 1, 1851).

- Truth is ever incoherent, and when the big hearts strike together, the concussion is a little stunning.

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 158

- I am heartily sorry I ever wrote anything about you — it was paltry. Lord, when shall we be done growing? As long as we have anything more to do, we have done nothing. So, now, let us add Moby-Dick to our blessing, and step from that. Leviathan is not the biggest fish; — I have heard of Krakens.

- Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 158

- It is — or seems to be — a wise sort of thing, to realise that all that happens to a man in this life is only by way of joke, especially his misfortunes, if he have them. And it is also worth bearing in mind, that the joke is passed round pretty liberally & impartially, so that not very many are entitled to fancy that they in particular are getting the worst of it.

- Letter to Samuel Savage (24 August 1851), as published in The Writings of Herman Melville : The Northwestern-Newberry Edition (1993), edited by Lynn Horth, Vol. 14, p. 203

- Whoever is not in the possession of leisure can hardly be said to possess independence. They talk of the dignity of work. Bosh. True Work is the necessity of poor humanity's earthly condition. The dignity is in leisure. Besides, 99 hundreths of all the work done in the world is either foolish and unnecessary, or harmful and wicked.

- Letter to Catherine G. Lansing (5 September 1877), published in The Melville Log : A Documentary Life of Herman Melville, 1819-1891 (1951) by Jay Leyda, Vol. 2, p. 765

- Instinct and study; love and hate;

Audacity — reverence. These must mate,

And fuse with Jacob’s mystic heart,

To wrestle with the angel — Art.- Timoleon, Art (1891)

- Indolence is heaven’s ally here,

And energy the child of hell:

The Good Man pouring from his pitcher clear

But brims the poisoned well.- Timoleon, Fragments of a Lost Gnostic Poem of the Twelfth Century, Fragment 2

- In armies, navies, cities, or families, in nature herself, nothing more relaxes good order than misery.

White-Jacket (1850)

[edit]

- It was not a very white jacket, but white enough, in all conscience, as the sequel will show.

The way I came by it was this...- Ch. 1, First lines

- Many sensible things banished from high life find an asylum among the mob.

- Ch. 7

- Oh, give me again the rover's life — the joy, the thrill, the whirl! Let me feel thee again, old sea! let me leap into thy saddle once more. I am sick of these terra firma toils and cares; sick of the dust and reek of towns. Let me hear the clatter of hailstones on icebergs, and not the dull tramp of these plodders, plodding their dull way from their cradles to their graves. Let me snuff thee up, sea-breeze! and whinny in thy spray. Forbid it, sea-gods! intercede for me with Neptune, O sweet Amphitrite, that no dull clod may fall on my coffin! Be mine the tomb that swallowed up Pharaoh and all his hosts; let me lie down with Drake, where he sleeps in the sea.

- Ch. 19

- Familiarity with danger makes a brave man braver, but less daring. Thus with seamen: he who goes the oftenest round Cape Horn goes the most circumspectly.

- Ch. 23

- In time of peril, like the needle to the loadstone, obedience, irrespective of rank, generally flies to him who is best fitted to command.

- Ch. 27

- We Americans are the peculiar, chosen people — the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of the liberties of the world.

- Ch. 36

- Though public libraries have an imposing air, and doubtless contain invaluable volumes, yet, somehow, the books that prove most agreeable, grateful, and companionable, are those we pick up by chance here and there; those which seem put into our hands by Providence; those which pretend to little, but abound in much.

- Ch. 41

- A man of true science... uses but few hard words, and those only when none other will answer his purpose; whereas the smatterer in science... thinks, that by mouthing hard words, he proves that he understands hard things.

- Ch. 63

- This has sometimes been paraphrased: A man thinks that by mouthing hard words he understands hard things. where "hard" can readily be taken to imply "harsh" words rather than those "difficult to understand".

- Are there no Moravians in the Moon, that not a missionary has yet visited this poor pagan planet of ours, to civilize civilisation and christianize Christendom?

- Ch. 64

- This has often been quoted with modernized American spelling, rendering it "to civilize civilization and christianize Christendom?"

- I had now been on board the frigate upward of a year, and remained unscourged; the ship was homeward-bound, and in a few weeks, at most, I would be a free man. And now, after making a hermit of myself in some things, in order to avoid the possibility of the scourge, here it was hanging over me for a thing utterly unforeseen, for a crime of which I was as utterly innocent. But all that was as naught.

- Ch. 67

- I cannot analyse my heart, though it then stood still within me. But the thing that swayed me to my purpose was not altogether the thought that Captain Claret was about to degrade me, and that I had taken an oath with my soul that he should not. No, I felt my man's manhood so bottomless within me, that no word, no blow, no scourge of Captain Claret could cut me deep enough for that. I but swung to an instinct in me — the instinct diffused through all animated nature, the same that prompts even a worm to turn under the heel. Locking souls-with him, I meant to drag Captain Claret from this earthly tribunal of his to that of Jehovah and let Him decide between us. No other way could I escape the scourge.

- Ch. 67

- Nature has not implanted any power in man that was not meant to be exercised at times, though too often our powers have been abused. The privilege, inborn and inalienable, that every man has of dying himself, and inflicting death upon another, was not given to us without a purpose. These are the last resources of an insulted and unendurable existence.

- Ch. 67

- I let nothing slip, however small; and feel myself actuated by the same motive which has prompted many worthy old chroniclers, to set down the merest trifles concerning things that are destined to pass away entirely from the earth, and which, if not preserved in the nick of time, must infallibly perish from the memories of man. Who knows that this humble narrative may not hereafter prove the history of an obsolete barbarism? Who knows that, when men-of-war shall be no more, "White-Jacket" may not be quoted to show to the people in the Millennium what a man-of-war was? God hasten the time!

- Ch. 68

- The worst of our evils we blindly inflict upon ourselves; our officers cannot remove them, even if they would. From the last ills no being can save another; therein each man must be his own saviour. For the rest, whatever befall us, let us never train our murderous guns inboard; let us not mutiny with bloody pikes in our hands. Our Lord High Admiral will yet interpose; and though long ages should elapse, and leave our wrongs unredressed, yet, shipmates and world-mates! let us never forget, that, Whoever afflict us, whatever surround, Life is a voyage that's homeward-bound!

- Ch. 93

Hawthorne and His Mosses (1850)

[edit]- Essay in The Literary World (August 17 & 24, 1850) - Full text online

- Would that all excellent books were foundlings, without father or mother, that so it might be, we could glorify them, without including their ostensible authors. Nor would any true man take exception to this; — least of all, he who writes, — "When the Artist rises high enough to achieve the Beautiful, the symbol by which he makes it perceptible to mortal senses becomes of little value in his eyes, while his spirit possesses itself in the enjoyment of the reality."

- The last sentence is a quotation of Nathaniel Hawthorne

- In this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a scared white doe in the woodlands; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself, as in Shakespeare and other masters of the great Art of Telling the Truth, — even though it be covertly, and by snatches.

- Since at least 1954 this has also been published at times as "Truth is forced to fly like a sacred white doe…", apparently a typographical error.

- It is better to fail in originality, than to succeed in imitation. He who has never failed somewhere, that man can not be great. Failure is the true test of greatness. And if it be said, that continual success is a proof that a man wisely knows his powers, — it is only to be added, that, in that case, he knows them to be small. Let us believe it, then, once for all, that there is no hope for us in these smooth pleasing writers that know their powers.

- Certain it is, however, that this great power of blackness in him derives its force from its appeals to that Calvinistic sense of Innate Depravity and Original Sin, from whose visitations, in some shape or other, no deeply thinking mind is always and wholly free. For, in certain moods, no man can weigh this world, without throwing in something, somehow like Original Sin, to strike the uneven balance.

- You must have plenty of sea-room to tell the truth in.

- Genius, all over the world, stands hand in hand, and one shock of recognition runs the whole circle round.

- I found that but to glean after this man, is better than to be in at the harvest of others.

- The truth seems to be, that like many other geniuses, this Man of Mosses takes great delight in hoodwinking the world, — at least, with respect to himself. Personally, I doubt not, that he rather prefers to be generally esteemed but a so-so sort of author; being willing to reserve the thorough and acute appreciation of what he is, to that party most qualified to judge — that is, to himself. Besides, at the bottom of their natures, men like Hawthorne, in many things, deem the plaudits of the public such strong presumptive evidence of mediocrity in the object of them, that it would in some degree render them doubtful of their own powers, did they hear much and vociferous braying concerning them in the public

Moby-Dick: or, the Whale (1851)

[edit]- These quotes are just a few samples, for more from this work, see the page for Moby-Dick

- Call me Ishmael.

- Ch. 1 : Loomings

- I have no objection to any person’s religion, be it what it may, so long as that person does not kill or insult any other person, because that other person don’t believe it also. But when a man’s religion becomes really frantic; when it is a positive torment to him; and, in fine, makes this earth of ours an uncomfortable inn to lodge in; then I think it high time to take that individual aside and argue the point with him.

- Ch. 17 : The Ramadan

- Old age is always wakeful; as if, the longer linked with life, the less man has to do with aught that looks like death.

- Ch. 29 : Enter Ahab; to Him, Stubb

- All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event — in the living act, the undoubted deed — there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask.

- Ahab to Starbuck, in Ch. 36 : The Quarter-Deck

- The drama's done. Why then here does any one step forth? — Because one did survive the wreck.

- Epilogue

Pierre: or, The Ambiguities (1852)

[edit]

- There are some strange summer mornings in the country, when he who is but a sojourner from the city shall early walk forth into the fields, and be wonder-smitten with the trance-like aspect of the green and golden world. Not a flower stirs; the trees forget to wave; the grass itself seems to have ceased to grow; and all Nature, as if suddenly become conscious of her own profound mystery, and feeling no refuge from it but silence, sinks into this wonderful and indescribable repose.

- First lines, Bk. I, ch. 1

- From without, no wonderful effect is wrought within ourselves, unless some interior, responding wonder meets it. That the starry vault shall surcharge the heart with all rapturous marvelings, is only because we ourselves are greater miracles, and superber trophies than all the stars in universal space. Wonder interlocks with wonder; and then the confounding feeling comes. No cause have we to fancy, that a horse, a dog, a fowl, ever stand transfixed beneath yon skyey load of majesty. But our soul's arches underfit into its; and so, prevent the upper arch from falling on us with unsustainable inscrutableness.

- Bk. III, ch. 1

- Thou hast evoked in me profounder spells than the evoking one, thou face! For me, thou hast uncovered one infinite, dumb, beseeching countenance of mystery, underlying all the surfaces of visible time and space.

- Bk. III, ch. 1

- But I shall follow the endless, winding way, — the flowing river in the cave of man; careless whither I be led, reckless where I land.

- Bk. V, ch. 7

- What we take to be our strongest tower of delight, only stands at the caprice of the minutest event — the falling of a leaf, the hearing of a voice, or the receipt of one little bit of paper scratched over with a few small characters by a sharpened feather.

- Bk. IV

- One trembles to think of that mysterious thing in the soul, which seems to acknowledge no human jurisdiction, but in spite of the individual's own innocent self, will still dream horrid dreams, and mutter unmentionable thoughts.

- Bk. IV

- A smile is the chosen vehicle of all ambiguities.

- Bk. IV, ch. 5

- All Profound things, and emotions of things are preceded and attended by Silence.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 1

- Silence is the general consecration of the universe. Silence is the invisible laying on of the Divine Pontiff's hands upon the world. Silence is at once the most harmless and the most awful thing in all nature. It speaks of the Reserved Forces of Fate. Silence is the only Voice of our God.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 1

- A paraphrase of the last portion of this has sometimes been cited as a quotation of Melville: God's one and only voice is silence.

- The more and the more that he wrote, and the deeper and the deeper that he dived, Pierre saw the everlasting elusiveness of Truth; the universal lurking insincerity of even the greatest and purest written thoughts. Like knavish cards, the leaves of all great books were covertly packed. He was but packing one set the more; and that a very poor jaded set and pack indeed. So that there was nothing he more spurned, than his own aspirations; nothing he more abhorred than the loftiest part of himself. The brightest success, now seemed intolerable to him, since he so plainly saw, that the brightest success could not be the sole offspring of Merit; but of Merit for the one thousandth part, and nine hundred and ninety-nine combining and dovetailing accidents for the rest.

- Bk. XXV, ch. 3

- His was the scorn which thinks it not worth the while to be scornful. Those he most scorned, never knew it.

- Bk. XXV, ch. 3

- Say what some poets will, Nature is not so much her own ever-sweet interpreter, as the mere supplier of that cunning alphabet, whereby selecting and combining as he pleases, each man reads his own peculiar lesson according to his own peculiar mind and mood.

- Bk. XXV, ch. 4

Bartleby, the Scrivener (1853)

[edit]- "At present I would prefer not to be a little reasonable," was his mildly cadaverous reply.

- Nothing so aggravates an earnest person as a passive resistance.

- Ah, happiness courts the light, so we deem the world is gay, but misery hides aloof, so we deem that misery there is none.

- And here Bartleby makes his home, sole spectator of a solitude which he has seen all populous- a sort of innocent and transformed Marius brooding among the ruins of Carthage!

- "I would prefer not to." (A line spoken repeatedly by Bartleby).

The Encantadas (1854)

[edit]

- If some books are deemed most baneful and their sale forbid, how, then, with deadlier facts, not dreams of doting men? Those whom books will hurt will not be proof against events. Events, not books, should be forbid.

- Sketch Eighth

Poor Man's Pudding and Rich Man's Crumbs (1854)

[edit]- Of all the preposterous assumptions of humanity over humanity, nothing exceeds most of the criticisms made on the habits of the poor by the well-housed, well-warmed, and well-fed.

- Well, there is sorrow in the world, but goodness too; and goodness that is not greenness, either, no more than sorrow is.

- Ch. 5

- I cannot tell you how thankful I am for your reminding me about the apocrypha here. For the moment, its being such escaped me. Fact is, when all is bound up together, it's sometimes confusing. The uncanonical part should be bound distinct. And, now that I think of it, how well did those learned doctors who rejected for us this whole book of Sirach. I never read anything so calculated to destroy man's confidence in man. This son of Sirach even says — I saw it but just now: 'Take heed of thy friends'; not, observe, thy seeming friends, thy hypocritical friends, thy false friends, but thy friends, thy real friends — that is to say, not the truest friend in the world is to be implicitly trusted. Can Rochefoucault equal that? I should not wonder if his view of human nature, like Machiavelli's, was taken from this Son of Sirach. And to call it wisdom — the Wisdom of the Son of Sirach! Wisdom, indeed! What an ugly thing wisdom must be! Give me the folly that dimples the cheek, say I, rather than the wisdom that curdles the blood. But no, no; it ain't wisdom; it's apocrypha, as you say, sir. For how can that be trustworthy that teaches distrust?"

- Ch. 45

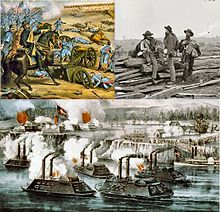

Battle Pieces: And Aspects of the War (1860)

[edit]

The night winds pause,

Recollecting themselves;

But no lull in these wars.

- With shouts the torrents down the gorges go,

And storms are formed behind the storm we feel:

The hemlock shakes in the rafter, the oak in the driving keel.- Misgivings, st. 2

- The poor old Past,

The Future's slave,

She drudged through pain and crime

To bring about the blissful Prime,

Then — perished. There's a grave!- The Conflict of Convictions, st. 6

- At the height of their madness

The night winds pause,

Recollecting themselves;

But no lull in these wars.- The Armies of the Wilderness, Pt. II, st. 5

- Youth is the time when hearts are large,

And stirring wars

Appeal to the spirit which appeals in turn

To the blade it draws.- On the Slain Collegians, st. 1

- What troops

Of generous boys in happiness thus bred —

Saturnians through life's Tempe led,

Went from the North and came from the South,

With golden mottoes in the mouth,

To lie down midway on a bloody bed.- On the Slain Collegians, st. 2

- Let us be Christians toward our fellow-whites, as well as philanthropists toward the blacks our fellow-men. In all things, and toward all, we are enjoined to do as we would be done by.

- Supplement

- There seems no reason why patriotism and narrowness should go together, or why intellectual impartiality should be confounded with political trimming, or why serviceable truth should keep cloistered be a cause not partisan. Yet the work of Reconstruction, if admitted to be feasible at all, demands little but common sense and Christian charity. Little but these? These are much.

- Supplement

- Patriotism is not baseness, neither is it inhumanity.

- Supplement

- Zeal is not of necessity religion, neither is it always of the same essence with poetry or patriotism.

- Supplement

- Benevolence and policy—Christianity and Machiavelli—dissuade from penal severities toward the subdued. Abstinence here is as obligatory as considerate care for our unfortunate fellow-men late in bonds, and, if observed, would equally prove to be wise forecast. The great qualities of the South, those attested in the War, we can perilously alienate, or we may make them nationally available at need.

- Supplement

- For the future of the freed slaves we may well be concerned; but the future of the whole country, involving the future of the blacks, urges a paramount claim upon our anxiety. Effective benignity, like the Nile, is not narrow in its bounty, and true policy is always broad.

- Supplement

- Amity itself can only be maintained by reciprocal respect, and true friends are punctilious equals.

- Supplement

Billy Budd, the Sailor (1891)

[edit]- Also known as Foretopman Billy Budd ; written in 1891 but not published until 1924; several varying renditions of it have since been published, drawing upon the notes of Melville.

- But are sailors, frequenters of fiddlers' greens, without vices? No; but less often than with landsmen do their vices, so called, partake of crookedness of heart, seeming less to proceed from viciousness than exuberance of vitality after long constraint: frank manifestations in accordance with natural law.

- Ch. 2

- Who in the rainbow can draw the line where the violet tint ends and the orange tint begins? Distinctly we see the difference of the colors, but where exactly does the one first blendingly enter into the other? So with sanity and insanity. In pronounced cases there is no question about them. But in some supposed cases, in various degrees supposedly less pronounced, to draw the exact line of demarcation few will undertake tho' for a fee some professional experts will. There is nothing nameable but that some men will undertake to do it for pay.

- Ch. 21

- In the light of that martial code whereby it was formally to be judged, innocence and guilt personified in Claggart and Budd in effect changed places. In a legal view the apparent victim of the tragedy was he who had sought to victimize a man blameless; and the indisputable deed of the latter, navally regarded, constituted the most heinous of military crimes.

- Ch. 21

- Says a writer whom few know, "Forty years after a battle it is easy for a non-combatant to reason about how it ought to have been fought. It is another thing personally and under fire to direct the fighting while involved in the obscuring smoke of it. Much so with respect to other emergencies involving considerations both practical and moral, and when it is imperative promptly to act."

- Ch. 21

- This statement is usually attributed entirely to Melville, but the way he presents it in the story indicates that he might be quoting a lesser known author.

- In war-time on the field or in the fleet, a mortal punishment decreed by a drum-head court — on the field sometimes decreed by but a nod from the General — follows without delay on the heel of conviction without appeal.

- Ch. 21

- If possible, not to let the men so much as surmise that their officers anticipate aught amiss from them is the tacit rule in a military ship. And the more that some sort of trouble should really be apprehended the more do the officers keep that apprehension to themselves; tho' not the less unostentatious vigilance may be augmented.

In the present instance the sentry placed over the prisoner had strict orders to let no one have communication with him but the Chaplain. And certain unobtrusive measures were taken absolutely to insure this point.- Ch. 23

- Billy's agony, mainly proceeding from a generous young heart's virgin experience of the diabolical incarnate and effective in some men — the tension of that agony was over now.

- Ch. 24

- Marvel not that having been made acquainted with the young sailor's essential innocence (an irruption of heretic thought hard to suppress) the worthy man lifted not a finger to avert the doom of such a martyr to martial discipline. So to do would not only have been as idle as invoking the desert, but would also have been an audacious transgression of the bounds of his function, one as exactly prescribed to him by military law as that of the boatswain or any other naval officer. Bluntly put, a chaplain is the minister of the Prince of Peace serving in the host of the God of War — Mars. As such, he is as incongruous as a musket would be on the altar at Christmas. Why then is he there? Because he indirectly subserves the purpose attested by the cannon; because too he lends the sanction of the religion of the meek to that which practically is the abrogation of everything but brute Force.

- Ch. 24

- At the penultimate moment, his words, his only ones, words wholly unobstructed in the utterance were these — "God bless Captain Vere!"

- Ch. 25

- The symmetry of form attainable in pure fiction can not so readily be achieved in a narration essentially having less to do with fable than with fact. Truth uncompromisingly told will always have its ragged edges...

- Ch. 28

- But me they'll lash me in hammock, drop me deep.

Fathoms down, fathoms down, how I'll dream fast asleep.

I feel it stealing now. Sentry, are you there?

Just ease this darbies at the wrist, and roll me over fair,

I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds about me twist.- Ch. 30, Billy in the Darbies

Misattributed

[edit]- We cannot live only for ourselves. A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men; and along these fibers, as sympathetic threads, our actions run as causes, and they come back to us as effects.

- Though this statement and a few other variants of it have been widely attributed to Herman Melville, it is actually a paraphrase of one found in a sermon of Henry Melvill, "Partaking in Other Men's Sins", St. Margaret's Church, Lothbury, England (12 June 1855), printed in Golden Lectures (1855) :

- There is not one of you whose actions do not operate on the actions of others—operate, we mean, in the way of example. He would be insignificant who could only destroy his own soul; but you are all, alas! of importance enough to help also to destroy the souls of others. ...Ye cannot live for yourselves; a thousand fibres connect you with your fellow-men, and along those fibres, as along sympathetic threads, run your actions as causes, and return to you as effects.

Quotes about Melville

[edit]

- under certain circumstances violence-acting without argument or speech and without counting the consequences-is the only way to set the scales of justice right again. (Billy Budd is the classical example.) In this sense, rage and the violence that sometimes-not always-goes with it belong among the "natural" human emotions, and to cure man of them would mean nothing less than to dehumanize or emasculate him. That such acts, in which men take the law into their own hands for justice's sake, are in conflict with the constitutions of civilized communities is undeniable; but their antipolitical character, so manifest in Melville's great story, does not mean that they are inhuman or "merely" emotional.

- Hannah Arendt Crises of the Republic (1972)

- Forty-four years ago, when his most famous tale, Typee, appeared, there was not a better known author than he, and he commanded his own prices. Publishers sought him, and editors considered themselves fortunate to secure his name as a literary star. And to-day? Busy New York has no idea he is even alive, and one of the best-informed literary men in this country laughed recently at my statement that Herman Melville was his neighbor by only two city blocks. "Nonsense," said he. "Why, Melville is dead these many years!" Talk about literary fame? There's a sample of it!

- Edward Bok, on Melville's final decades of life in relative obscurity, in Publishers' Weekly (15 November 1890)

- Most of the books published during the five-year period leading up to, during, and after the invasion of Mexico were war-mongering tracts. Euro-American settlers were nearly all literate, and this was the period of the foundational "American literature," with writers James Fenimore Cooper, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville all active-each of whom remains read, revered, and studied in the twenty-first century, as national and nationalist writers, not as colonialists. Although some of the writers, like Melville and Longfellow, paid little attention to the war, most of the others either fiercely supported it or opposed it.

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (2014)

- It was during the 1820s-the beginning of the era of Jacksonian settler democracy-that the unique US origin myth evolved reconciling rhetoric with reality. Novelist James Fenimore Cooper was among its initial scribes. Cooper's reinvention of the birth of the United States in his novel The Last of the Mohicans has become the official US origin story. Herman Melville called Cooper "our national novelist."

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (2014)

- On one meeting Melville showed Hawthorne a draft of Moby-Dick. Hawthorne, himself currently completing The Scarlet Letter, persuaded his friend to rework it from a tale of the high seas to an epic allegory that told not only a tale, but probed the defeats and triumphs of the human spirit. Melville delayed his submission to his publishers until it could meet Hawthorne's exacting standards. When it did, Hawthorne at last pronounced that the tragic tale was "cooked in hellfire." It was the praise Melville had sought.

- Marlene Wagman-Geller, on some of the reasons for Melville's dedication of Moby-Dick: "In Token of my admiration for his genius this book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne", in Once Again to Zelda : The Stories Behind Literature's Most Intriguing Dedications (2008), p. 13

- Melville and I had a talk about time and eternity, things of this world and next, and books, and publishers, and all possible and impossible matters, that lasted pretty deep into the night.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, quoted in Once Again to Zelda : The Stories Behind Literature's Most Intriguing Dedications (2008), by Marlene Wagman-Geller, p. 13

- Melville, as he always does, began to reason of Providence and futurity, and of everything that lies beyond human ken, and informed me that he "pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated"; but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation; and, I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. It is strange how he persists — and has persisted ever since I knew him, and probably long before — in wandering to-and-fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sand hills amid which we were sitting. He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other. If he were a religious man, he would be one of the most truly religious and reverential; he has a very high and noble nature, and better worth immortality than most of us.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, entry for 20 November 1856, in The English Notebooks, (1853 - 1858)

- A man with true, warm heart, and a soul and an intellect, — with life to his fingerprints; earnest, sincere, and reverent; very tender and modest. And I am not sure that he is not a very great man. He has very keen perceptive power; but what astonishes me is, that his eyes are not large and deep. He seems to me to see everything accurately; and how he can do so with his small eyes, I cannot tell. They are not keen eyes, either, but quite undistinguished in any way. His nose is straight and handsome, his mouth expressive of sensibility and emotion. He is tall and erect, with an air free, brave, and manly. When conversing, he is full of gesture and force, and loses himself in his subject. There is no grace or polish. Once in a while, his animation gives place to a singularly quiet expression, out of those eyes to which I have objected; an indrawn, dim look, but which at the same time makes you feel that he is at that instant taking deepest note of what is before him. It is a strange, lazy glance, but with a power in it quite unique. It does not seem to penetrate through you, but to take you into itself.

- Sophia Hawthorne, in a letter to her mother (1850), as quoted in Herman Melville : Mariner and Mystic (1921) by Raymond Melbourne Weaver, p. 24

- Nobody had more class than Melville. To do what he did in Moby-Dick, to tell a story and to risk putting so much material into it. If you could weigh a book, I don’t know any book that would be more full. It’s more full than War and Peace or The Brothers Karamazov. It has Saint Elmo’s fire, and great whales, and grand arguments between heroes, and secret passions. It risks wandering far, far out into the globe. Melville took on the whole world, saw it all in a vision, and risked everything in prose that sings. You have a sense from the very beginning that Melville had a vision in his mind of what this book was going to look like, and he trusted himself to follow it through all the way.

- I was trying to describe a veteran of the Vietnam War, and I kept thinking of him as Billy Budd. I wondered, "Is this a correct comparison?" So I read it again today, and I realized that the book is about war. I didn't think about that before; I just thought it was about somebody good who was on a ship. I didn't remember the war. In those days they weren't drafted, they were impressed. The captain in the book even says, "Use the right word for it, it's impressment." Billy Budd is a draftee. And he goes along with it. The story is about mutiny within the military during wartime.

- 1996 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- Herman Melville, whose work I loved

- Irena Klepfisz "Secular Jewish Identity: Yidishkayt in America" (1986) in Dreams of an Insomniac (1990)

- THE greatest seer and poet of the sea for me is Melville. His vision is more real than Swinburne's, because he doesn't personify the sea, and far sounder than Joseph Conrad's, because Melville doesn't sentimentalize the ocean and the sea's unfortunates. Melville at his best invariably wrote from a sort of dreamself, so that events which he relates as actual fact have indeed a far deeper reference to his own soul, his own inner life. Melville was, at the core, a mystic and an idealist.

- if Herman Melville would have written "Moby Dick" in South Africa, it would be immediately taken for a fable about whites and blacks. In Latin America, they would read "Moby Dick" as a fable about macho and revolution. Some countries are probably doomed to have their literatures immediately interpreted in a general way.

- Amos Oz interview with NPR (1988)

- Herman Melville is a god. … I cherish what he did. He was a genius. Wrote Moby-Dick. Wrote Pierre. Wrote The Confidence-Man, wrote Billy Budd. … Oh, yes — look at him. … Scares the bejesus out of people and makes them hate him. Because he's so good. Claggart has him killed in that book. Claggart has his eye on that boy. He will not tolerate such goodness, such blondeness, such blue eye. Goodness is scary. It's like you want to knock it. You want to hit it.

- I've had my career. I've had my success. God willing, it should have happened to Herman Melville who deserved it a great deal more, you know? Imagine him being on Bill Moyers' show. Nothing good happened to Herman Melville.

- Maurice Sendak, in an interview, "NOW with Bill Moyers", PBS (12 March 2004)

Editorial eulogy in The New York Times (2 October 1891)

[edit]a few days after a brief obituary had appeared on 29 September 1891

- There has died and been buried in this city, during the current week, at an advanced age, a man who is so little known, even by name, to the generation now in the vigor of life that only one newspaper contained an obituary account of him, and this was but of three or four lines. Yet forty years ago the appearance of a new book by Herman Melville was esteemed a literary event, not only throughout his own country, but so far as the English-speaking race extended. To the ponderous and quarterly British reviews of that time, the author of Typee was about the most interesting of literary Americans, and men who made few exceptions to the British rule of not reading an American book not only made Melville one of them, but paid him the further compliment of discussing him as an unquestionable literary force. Yet when a visiting British writer a few years ago inquired at a gathering in New-York of distinctly literary Americans what had become of Herman Melville, not only was there not one among them who was able to tell him, but there was scarcely one among them who had ever heard of the man concerning whom he inquired, albeit that man was then living within a half mile of the place of the conversation. Years ago the books by which Melville's reputation had been made had long been out of print and out of demand.

- In its kind this speedy oblivion by which a once famous man so long survived his fame is almost unique, and it is not easily explicable. Of course, there are writings that attain a great vogue and then fall entirely out of regard or notice. But this is almost always because either the interest of the subject matter is temporary, and the writings are in the nature of journalism, or else the workmanship to which they owe their temporary success is itself the produce or the product of a passing fashion. This was not the case with Herman Melville. Whoever, arrested for a moment by the tidings of the author's death, turns back now to the books that were so much read and so much talked about forty years ago has no difficulty in determining why they were then read and talked about. His difficulty will be rather to discover why they are read and talked about no longer. The total eclipse now of what was then a literary luminary seems like a wanton caprice of fame. At all events, it conveys a moral that is both bitter and wholesome to the popular novelists of our own day.

- Melville was a born romancer. One cannot account for the success of his early romances by saying that in the Great South Sea he had found and worked a new field for romance, since evidently it was not his experience in the South Sea that had led him to romance, but the irresistible attraction that romance had over him that led him to the South Sea. He was able not only to feel but to interpret that charm, as it never had been interpreted before, as it never has been interpreted since.

External links

[edit]- Works by Herman Melville at Project Gutenberg

- Brief biography at Kirjasto (Pegasos)

- Online version of Billy Budd - Edited by David Padilla (University of Virginia)

- The Confidence-Man (University of Virginia)

Categories:

- 1819 births

- 1891 deaths

- Essayists from the United States

- Humanists

- Novelists from the United States

- People from New York City

- Philosophical pessimists

- Poets from the United States

- 19th-century poets from the United States

- Short story writers from the United States

- Travel writers

- Educators from the United States

- Sailors

- Presbyterians from the United States

- Unitarians from the United States