Cloning

Appearance

In biology, cloning is the process of producing similar populations of genetically identical individuals that occurs in nature when organisms such as bacteria, insects or plants reproduce asexually. Cloning in biotechnology refers to processes used to create copies of DNA fragments (molecular cloning), cells (cell cloning), or organisms. The term also refers to the production of multiple copies of a product such as digital media or software.

Quotes

[edit]

- The first obstacle to cloning your dog is that $100,000 cost. The second is getting the right kind of cells.

It's easier if your dog is still alive, in which case you just take it to the vet to get a biopsy sample, an 8-millimeter piece of skin from the abdomen, or about half the width of a penny. Then you pack those samples into an ice-pack-filled plastic-foam box and mail the box to Sooam.

You can clone a dog that has been dead for fewer than five days, too, as long as you wrap its body in wet towels and place it in a refrigerator, which keeps it from drying out before getting to the vet. If the dog is dead, Sooam asks that you send as many skin samples as possible so that the lab has a better chance of finding living cells.- Drake Baer, (8 September 2015). "This Korean lab has nearly perfected dog cloning, and that's just the start". Tech Insider, Innovation. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- A prominent biologist Lee Silver, once said that biology would be forever defined as BD and AD: before Dolly and after Dolly. Such is the enormity of the findings of the Roslin Institute, where not only was Dolly the sheep created, but her predecessors Tracy, Megan and Morag. These animals are important in terms of their significance to science and the ethical issues that their creation raises.

- BBC, "Gene Genie | BBC World Service", Bbc.co.uk, 2000-05-01.

- Wilmut has always been clear about his ethical beliefs and has publicly voiced his approval of 'therapeutic cloning', whilst strongly opposing anyone attempting to clone a human, claiming that they are 'very naïve'. He allays any fears that cloning would produce identical humans and explains that unlike identical twins, clones are derived from different eggs, developed in different uterus and most likely have different mothers. However, his condemnation of human cloning lies in both the process and the overall practical benefits. 'I don't like the idea of copying a person' he explains, 'because I think that each child should be wanted as an individual.' There are also practical considerations,

'we are one of the labs who are trying to clone a pig, with the aim that one day pigs will provide organs for transplantation into human patients - there is a real biological need there. In the process we have probably worked with over four or five thousand embryos without any success. Just where exactly would you get this many human embryos? It is obscene to even think about doing that to people.'- BBC, "Gene Genie | BBC World Service", Bbc.co.uk, 2000-05-01.

- Hard lessons have been learnt by past situations involving science and secrecy. Nobel Peace Prize winner Joseph Rotblat said of Dolly's creation that 'it was as important as the building of the atomic bomb.'

- BBC, "Gene Genie | BBC World Service", Bbc.co.uk, 2000-05-01.

- First, a suitable surrogate mother animal is required. For the mammoth this would need to be a cow (as best biological fit) but even here the size difference may preclude gestation to term.

- BBC News, “Russian scientists to attempt clone of woolly mammoth”, Bbc.co.uk, 2011-12-07.

- If there are intact cells in this tissue they have been 'stored' frozen. However, if we think back to what actually happened to the animal - it died, even if from the cold, the cells in the body would have taken some time to freeze. This time lag would allow for breakdown of the cells, which normally happens when any animal dies. Then the carcass would freeze. So it is unlikely that the cells would be viable.

- BBC News, “Russian scientists to attempt clone of woolly mammoth”, Bbc.co.uk, 2011-12-07.

- "Let's say that one in a thousand cells were nevertheless viable, practical issues come into play. Given that we have an efficiency of 1% cloning for livestock species and if only one in a thousand cells are viable then around 100,000 cells would need to be transferred," it said.

- BBC News, “Russian scientists to attempt clone of woolly mammoth”, Bbc.co.uk, 2011-12-07.

- Considered contrary to the moral law, since (it is in) opposition to the dignity both of human procreation and of the conjugal union.

- Donum Vitae Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith (1987) [1]

- The delivered kid was genetically identical to the bucardo. In species such as bucardo, cloning is the only possibility to avoid its complete disappearance.

- Jose Folch in Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning” Richard Gray and Roger Dobson, (Jan 2009).

- Dr. Josef Mengele: Do you know what I saw on the television in my motel room at one o'clock this morning? Films of Hitler! They are showing films about the war! The movement! People are fascinated! The time is ripe! Adolf Hitler is alive! [Takes photo album and places it on his lap] This album is full of pictures of him. Bobby Wheelock and ninety-three other boys are exact genetic duplicates of him, bred entirely from his cells. He allowed me to take half a liter of his blood and a cutting of skin from his ribs. [laughs] We were in a Biblical frame of mind on the twenty-third of May 1943, at the Berghof. He had denied himself children because he knew that no son could flourish in the shadow of so godlike a father! But when he heard what was theoretically possible, that I could create one day not his son, not even a carbon-copy but another original, he was thrilled by the idea! The right Hitler for the right future! A Hitler tailor-made for the 1980s, the 1990s, 2000!

- Heywood Gould, The Boys from Brazil (1978); based on the novel by Ira Levin.

- Proponents of human reproductive cloning do not dispute that cloning may lead to violations of clones' right to self‐determination, or that these violations could cause psychological harms. But they proceed with their endorsement of human reproductive cloning by dismissing these psychological harms, mainly in two ways. The first tactic is to point out that to commit the genetic fallacy is indeed a mistake; the second is to invoke Parfit's non‐identity problem.

- Havstad JC (2010). "Human reproductive cloning: a conflict of liberties". Bioethics. 24 (2): 71–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00692.x. PMID 19076121.

- Populations with low numbers of individuals possess minimal genetic variation. It is therefore desirable to avoid further losses of diversity. A subsequent generation resulting from natural breeding or artificial insemination (AI) would contain some, but not all, of the genetic variability of its parents. Losses would occur if any of the individuals failed to breed, a strong possibility with small populations. If cloning was guaranteed to be 100% successful, a good strategy might be to clone every individual (not impossible if the population size is only 9–18), then allow the offspring to mature and breed naturally. The probability of losing genetic diversity would then be reduced, especially if each parent gave rise to more than two identical copies of itself. Thus, an interesting and novel theoretical principle in animal conservation emerges, where individuals are effectively induced to reproduce asexually, somewhat like plants, thereby improving the long-term fitness of the species through the retention of genetic diversity.

- Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S., "Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning", Reproduction, 126, (2004)

- Current success rates with nuclear transfer in mammals are very low (less than 0.1–5% of reconstructed embryos result in a live birth (Di Berardino 2001, Wakayama & Yanagimachi 2001). Therefore, between 20 and 1000 nuclear transfers would need to be performed to achieve one viable offspring.

- Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S., "Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning", Reproduction, 126, (2004)

- Several attempts at cloning exotic or endangered species have received widespread publicity (e.g. Gaur (Bos gaurus), Banteng (Bos javanicus) and Bucardo (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica)). The distinguishing feature of these examples is that they employed trans-species cloning (Fig. 2⇓). In these instances, the oocyte cytoplasm being used to create embryos was derived from common domesticated species (Bos taurus (cow) or Capra hircus (goat)), while the cell nucleus was from the species of interest. Trans-species clones inevitably differ from either of the parental species in their nucleo-cytoplasmic characteristics. At the very least, mitochondria inherited from the recipient oocyte would have a major influence over functions, such as muscle development and physiology, that depend on mitochondrial gene expression. Animals resulting from these trans-specific cloning efforts would be scientifically valuable for their insights into the functional relationships involved in nucleo-mitochondria dialogue, but would not be directly useful for supporting the endangered populations.

- Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S., "Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning", Reproduction, 126, (2004)

- Developments in biotechnology have raised new concerns about animal welfare, as farm animals now have their genomes modified (genetically engineered) or copied (cloned) to propagate certain traits useful to agribusiness, such as meat yield or feed conversion. These animals have been found to suffer from unusually high rates of birth defects, disabilities, and premature death.

- Humane Society of the United States, "An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Genetic Engineering and Cloning of Farm Animals", p.1

- "Therapeutic cloning will hopefully be the solution for all the problems that have plagued transplant medicine for many years -- the shortage of tissue and rejection. Stem cells lines are basically immortal and with them we can turn them into any cell type," Robert Lanza, chief scientist for Advance Cell Technology, a U.S. company involved in regenerative medicine.

- Dean Irvine, "You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com", Edition.cnn.com, (2007-11-19).

- Helen Wallace is more skeptical and wary about the demands on women from human cloning: "Claims that you could clone individual treatments of human beings to treat common diseases like diabetes, suggests you need a huge supply of human eggs. Where are they going to come from? Even if you don't have a religious view of the sanctity of life, you have to ask is there going to be a massive trade in human eggs from poor women to rich countries."

- Dean Irvine, "You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com", Edition.cnn.com, (2007-11-19).

- For Lanza, reproductive cloning is "like sending up a rocket knowing it's got a 25 percent chance it's going to blow up -- it's just not ethical."

- Dean Irvine, "You, again: Are we getting closer to cloning humans? - CNN.com", Edition.cnn.com, (2007-11-19).

- The Doctor: She hates her own clones. She burns her own clones. Frankly, you're a career break for the right therapist.

- Steven Moffat, "Time Heist", Doctor Who, (September 20, 2014).

- Some ethicists regard the cloning of humans as inherently evil, a morally unjustifiable intrusion into human life. Others measure the morality of any act by the intention behind it; still others are concerned primarily with the consequences-for society as well as for individuals. Father Richard McCormick, a veteran Jesuit ethicist at the University of Notre Dame, represents the hardest line: any cloning of humans is morally repugnant. A person who would want a clone of himself, says McCormick, "is overwhelmingly self-centered. One Richard McCormick is enough." But why not clone another Einstein? Once you program for producing superior beings, he says, you are into eugenics, "and eugenics of any kind is inherently discriminatory." What's wrong with duplicating a sibling whose bone marrow could save a sick child? That, he believes, is using another human being merely "as a source for replaceable organs." But why shouldn't an infertile couple resort to cloning if that is the only means of having a child? "Infertility is not an absolute evil that justifies doing any and every thing to overcome it," McCormick insists.

- Richard McCormick; in "Today The Sheep..." Newsweek. 9 March 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- This study demonstrates, to our knowledge for the first time, that adult neurons can be cloned by nuclear transfer. Furthermore, our data imply that reduced amounts of H3K9me2 and increased histone acetylation appear to act synergistically to improve the development of cloned embryos.

- Ono T, Li C, Mizutani E, Terashita Y, Yamagata K, Wakayama T (Dec 2010). Inhibition of class IIb histone deacetylase significantly improves cloning efficiency in mice". Biol. Reprod. 83 (6), ,p.1

- The body of text, the bodies of letters: flesh is hereto be given to DNA analysis, taking the risk of being used in the future, and that a body, a replicant, a clone can be constructed.

- Orlan, "ORLAN: A Hybrid Body of Artworks", edited by Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd p. 47.

- Meet Bessie, who could soon be the first cow to give birth to a cloned ox.

If she delivers the rare Asian gaur growing inside her, she will herald a stunning new way to save endangered, or even recently extinct, animals.

The bovine surrogate mother is carrying the gaur fetus on a farm near Sioux City, Iowa, and is expected to give birth to "Noah" next month.

"He will be the first endangered animal we send up the ramp of the ark," said Robert Lanza, the vice president of medical and scientific development at Advanced Cell Technology, and one of the lead authors of a study published Sunday in the journal Cloning. "This is no longer science fiction. It's very, very real."- Heidi B. Perlman (2000-10-08). "Scientists Close on Extinct Cloning". The Washington Post. Associated Press.

- It is also our view that there are no sound reasons for treating the early-stage human embryo or cloned human embryo as anything special, or as having moral status greater than human somatic cells in tissue culture. A blastocyst (cloned or not), because it lacks any trace of a nervous system, has no capacity for suffering or conscious experience in any form – the special properties that, in our view, spell the difference between biological tissue and a human life worthy of respect and rights. Additional biological facts suggest that a blastocyst should not be identified with a unique individual person, even if the argument that it lacks sentience is set aside. A single blastocyst may, until the primitive streak is formed at around fourteen days, split into twins; conversely, two blastocysts may fuse to form a single (chimeric) organism. Moreover, most early-stage embryos that are produced naturally (that is, through the union of egg and sperm resulting from sexual intercourse) fail to implant and are therefore wasted or destroyed.

- The President's Council on Bioethics, "Human Cloning and Human Dignity: An Ethical Inquiry", Washington, D.C., (July 2002).

- SNCT is a widely used cloning technique whereby a cell nucleus containing the genetic information of the individual to be cloned is inserted into a living egg that has had its own nucleus removed. It has been used successfully in laboratory animals as well as farm animals.

However, until now, scientists hadn't been able to overcome the limitations of SNCT that resulted in low success rates and restricted the number of times mammals could be recloned. Attempts at recloning cats, pigs and mice more than two to six times had failed.

"One possible explanation for this limit on the number of recloning attempts is an accumulation of genetic or epigenetic abnormalities over successive generations," explains Dr. Wakayama.- RIKEN, "Generations of Cloned Mice With Normal Lifespans Created: 25th Generation and Counting". Science Daily. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Dr Singla added, "Without cloning, one buffalo would have given birth to a single offspring every year. Through cloning, we can get surrogate mothers to give birth to 40-50 calves every year."

- Kounteya Sinha (2009-02-13). "India clones world's first buffalo". The Times of India. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- Critics worry the cloning of endangered species could hamper efforts to conserve biodiverse habitats by offering a sort of "silver bullet" solution to saving endangered species.

- Kate Tobin, "First cloned endangered species dies 2 days after birth". CNN. 12 January 2001. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "When you get down to a few dozen members of a species you're really talking about very serious problems," Lanza said. "So this is a tool. From now on that there's no need ever really to ever lose that genetic diversity that's remaining in these wild populations."

- Kate Tobin, "First cloned endangered species dies 2 days after birth". CNN. 12 January 2001. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- In a first, Mitalipov and his privately funded team report that these cloned embryos were grown past an eight-cell size (where earlier attempts had stopped) into a full-blown early embryo, containing hundreds of embryonic stem cells. Embryonic cells taken from these cloned embryos were grown into six colonies of cells, the first successfully grown cloned human embryonic stem cells. The embryos were destroyed in the cell collection process.

Some of the cells were successfully prompted to become more specialized skin and heart cells. That is the next step in someday using the cells in "regenerative" medicine, where cells cloned from a patient would be used to grow into transplant organs to treat diseases and injuries such as paralysis.

"For stem cell biology, there will be history before this result and then history after it with the study as the dividing line," says stem cell researcher Paul Knoepflerof the University of California, Davis. "No doubt This is a real milestone."- Dan Vergano, "Human embryonic stem cells are cloned”, USA Today, (May 15, 2013).

- Since 1998, when a University of Wisconsin team first isolated embryonic stem cells grown from a human embryo, researchers have sought to use cloning techniques to create such cells that would be genetic copies of ones belonging to sick patients. The same cloning techniques, which essentially place a new set of genes into a hollowed-out egg, and then kick-start the combination to start dividing and become an embryo, have been used since the cloning of "Dolly the Sheep" in 1996. That helped to create genetic copies, twins, of animals ranging from prize bulls to an extinct kind of wild goat. In those cases, the embryos were implanted into a surrogate mother instead of being destroyed to harvest stem cells.

Knoepfler warned that fertility clinic operators outside the USA might try to replicate the team's method to try to clone a human baby. However, Mitalipov says that his team's technique would not likely create a cloned embryo that could be implanted into a surrogate mother's womb and lead to a pregnancy. "The embryos we produce this way did not lead to pregnancy in monkeys," he says. "We think there is something in the manipulations to make them that make a successful pregnancy impossible."- Dan Vergano, "Human embryonic stem cells are cloned”, USA Today, (May 15, 2013).

- The real significance of the advance may be to re-ignite debate over human cloning, says bioethicist Insoo Hyun of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

"Basically, FDA has jurisdiction over clinical research using cloning technology to create a human being," says the Food and Drug Administration's Curtis Allen. "To date, FDA has not licensed such a therapy."

"No legitimate scientists would want to use this technology for reproductive purposes," says stem cell expert George Daley of Children's Hospital Boston. "They would see it not only as unethical, but unsafe and probably illegal."

Still, "This study shows that human cloning can be done," said Richard Doerflinger of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, which opposes research that destroys embryos. "The more important debate is whether it should be done."- Dan Vergano, "Human embryonic stem cells are cloned”, USA Today, (May 15, 2013).

- No doubt the person whose experimental skill will eventually bring forth a clonal baby will be given wide notoriety. But the child who grows up knowing that the world wants another Picasso may view his creator in a different light.

- James Watson, Moving toward the Clonal Man (1971).

- It's a different way to begin separating out nature and nurture, and to see how different this boy would be. But I have many times been asked if my children have followed me into research — it's something people subconsciously expect. For a clone, the pressure would be even greater. People would expect the clone to be like the original, and put expectations and limitations on them, and that's the reason why I don't like to use that technique. I think people should be wanted as individuals.

- Ian Wilmut, “A Talk With Dolly's Creator“ TIME, (Monday, July 03, 2006).

Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", (March 2007)

[edit]- The FDA claims that the scientific evidence shows that food from clones is no different than other food. But any attempt to evaluate the current science on the foods safety of products from clones is doomed to fail, as there have been virtually no peer-reviewed scientific studies designed for evaluating cloned food.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 5

- Since FDA could not find studies on milk or meat from clones, the Agency chose to assess the safety of these foods indirectly, by looking at studies that investigated basic issues about cloning technology.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 5

- For the post-puberty period in cow clones, for example, FDA says that "Most of the possible food consumption risks arising from edible products of clones (E.g., milk or meat) would occur during this Developmental Node," but the Agency notes that "little information is available on animals during this developmental phase, and much of that information comes in the form of single sentences or short mentions in journal articles that address some other issue."

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 6

- Hydrops, an abnormality common in cloning in which fluid builds-up in the fetus and/or placenta, can lead to abortion, stillbirths, or early deaths of clones, and usually results in euthanasia of surrogate cows. The incidence of hydrops in cloning is as high as 42%, but in natural breeding or other assisted technologies the condition is extremely rare, with estimates as low as 1 in 7500.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 7

- FDA notes that "early reports, beginnning in 1998, of clone moraltiy rates were 50 to 80 percent," but states that more recent studies show better results, with mortality rates dropping to around 20%.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 11

- A 2005 study cited by FDA, on semen quality from two clones, found clones has a lower pregnancy rate (55% compared to 63%) than natural comparators and almost double the rate of spontaneous abortions. A 2004 study found that the range of rates of development to blastocyst for embryos fertilized in vitro by sperm from six bull clones was lower than that of comparators, while pregnancy and calcing rates of clones were 83%, compared to 90% for comaprators.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 12

- On meat consumption, FDA notes only that "differences in meat nutrient composition were very small...." But its chart comparing nutrient levels in cloned versus natural pigs shows clones have lower levels of all except one amino acid, while cholesterol and all except two fatty acid levels were higher for clones.The agency offers no explanation or dicussion of these findings.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 13

- FDA's "Animal Health" section for the post-puberty period in pig clones consists of a single sentence: "No reports on aging and maturity in swine clones were identified." The Agency later repeats that it "was not able to identify any peer-reviewed studies on non-reproductive postpubertal studies (sic) in swine clones." Thus, the Agency relies solely on the Viagen data for this period, which, as noted above, consisted of data on just five clones, and found that clones weighed less than natural comparator animals and had reduced marbling and back-fat thickness.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 15

- FDA has a long history of interpreting the definition of a “new drug” broadly, basing it on the functional claim intended from a new technology. Under the FFDCA, new drugs include “articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.”220 Thus, for example, FDA is currently reviewing genetically engineered (GE) “fast growing” salmon under its “new animal drug” authority, because the GE fish is structurally and functionally affected by the technology. Similarly, cloning companies claim that their technology will affect both the structure and function of the cloned animal, by producing animals with improved meat qualities or high-yielding dairy animals. Furthermore, cloning experts say that the cloning technology is the same in animals as it would be in humans, and FDA has already stated that any human cloning research would be regulated as a new drug by the agency under FFDCA, and would require submission of an “investigational new drug application.”221 FDA offers no explanation as to why animal cloning should be exempted from the rigorous new drug review procedures that it requires for human cloning research.

- Center for Food Safety, "Not Ready for Prime Time: FDA's Flawed Approach to Assessing the Safety of Food from Animal Clones", March 2007, p. 19

Human Genome Project Information, "Cloning Fact Sheet" (Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011)

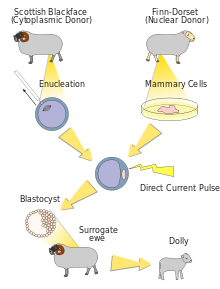

[edit]- Reproductive cloning is a technology used to generate an animal that has the same nuclear DNA as another currently or previously existing animal. Dolly was created by reproductive cloning technology. In a process called "somatic cell nuclear transfer" (SCNT), scientists transfer genetic material from the nucleus of a donor adult cell to an egg whose nucleus, and thus its genetic material, has been removed. The reconstructed egg containing the DNA from a donor cell must be treated with chemicals or electric current in order to stimulate cell division. Once the cloned embryo reaches a suitable stage, it is transferred to the uterus of a female host where it continues to develop until birth.

Dolly or any other animal created using nuclear transfer technology is not truly an identical clone of the donor animal. Only the clone's chromosomal or nuclear DNA is the same as the donor. Some of the clone's genetic materials come from the mitochondria in the cytoplasm of the enucleated egg. Mitochondria, which are organelles that serve as power sources to the cell, contain their own short segments of DNA. Acquired mutations in mitochondrial DNA are believed to play an important role in the aging process.- Human Genome Project Information, "Cloning Fact Sheet" (Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011. )

- Reproductive cloning is expensive and highly inefficient. More than 90% of cloning attempts fail to produce viable offspring. More than 100 nuclear transfer procedures could be required to produce one viable clone. In addition to low success rates, cloned animals tend to have more compromised immune function and higher rates of infection, tumor growth, and other disorders.

- Human Genome Project Information, "Cloning Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- In 2002, researchers at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, reported that the genomes of cloned mice are compromised. In analyzing more than 10,000 liver and placenta cells of cloned mice, they discovered that about 4% of genes function abnormally. The abnormalities do not arise from mutations in the genes but from changes in the normal activation or expression of certain genes.

Problems also may result from programming errors in the genetic material from a donor cell. When an embryo is created from the union of a sperm and an egg, the embryo receives copies of most genes from both parents. A process called "imprinting" chemically marks the DNA from the mother and father so that only one copy of a gene (either the maternal or paternal gene) is turned on. Defects in the genetic imprint of DNA from a single donor cell may lead to some of the developmental abnormalities of cloned embryos.

Due to the inefficiency of animal cloning (only about 1 or 2 viable offspring for every 100 experiments) and the lack of understanding about reproductive cloning, many scientists and physicians strongly believe that it would be unethical to attempt to clone humans. Not only do most attempts to clone mammals fail, about 30% of clones born alive are affected with "large-offspring syndrome" and other debilitating conditions.- Human Genome Project Information, "Cloning Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27)

[edit]- Given the paucity of data that directly address the safety of meat and milk from cloned animals, the FDA used indirect measures of food safety, primarily data on the health of the clones at different life stages. The operating hypothesis is the notion that an animal that appears healthy must be safe to eat (e.g. the Critical Biological Systems Approach). This approach is not scientific—this is reasoning by inference, not from data. Furthermore, FDA has bent over backward to interpret data from cloning companies in a way that minimizes the potential problems raised by SCNTs. Both of these problems need to be remedied in the final Risk Assessment.

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 2

- It is clear from studies FDA reviewed on animal health that clones have higher rates of illness and death than non-clone comparators, particularly at the younger ages. This could lead to greater use of drugs on clones, which in turn could exacerbate antibiotic resistance. FDA’s Risk Assessment failed to assess this risk. In both cloned cattle and sheep, one of the biggest health problems is large offspring syndrome (LOS). As the name implies, LOS refers to offspring that are abnormally large at birth, but they also have a range of other abnormalities. FDA lists 11 clinical signs associated with LOS, including fetus weight more than 20% larger than average for the breed, deformities of limb and/or head, disproportionate or immature organ development, increased susceptibility to infection, and cardio vascular problems. Since cattle with LOS tend to have increased susceptibility to infection, there would be a greater need for antibiotics and other drugs to help fight the infections in those LOS cattle. Although LOS doesn’t appear to happen normal reproduction or AI, it does happen with some of the ARTs, such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF), embryo culture, as well as with SCNTs

- Michael Hansen, (2007-04-27). "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, p. 10

- In sum, contrary to FDA, we feel the data on offspring of clones are disturbing— particularly the increase in preweaning death rates of offspring of clones compared to offspring of comparators and the increases in the rate blood measurements (both hematology and clinical chemistry) being considered outliers (e.g. extreme values) to increase over time with the offspring of clones while it decreases over time with offspring of comparators. The fact that any differences were seen in offspring of clones compared to offspring of comparators deserves much more scrutiny. Clones are known have much higher preweaning death rates compared to non-clones. The fact that preweaning death rate of offspring of clones was higher, depending on clone source, compared to offspring of non-clones, suggest that some of the adverse health impacts in clones are being passed on to their offspring and so should deserve much more scrutiny. Instead, FDA tries to explain away all this troubling data so that they can conclude that offspring of clones are not that different than offspring of non-clone comparators.

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 15

- The notion that clones are “identical twins born at different times” is scientifically wrong and very misleading. There is a fundamental distinction between identical twins produced naturally and a SCNT “clone.” Identical twins normally arise by the splitting of an already fertilized egg, so that the two twins share not only the same genetic complement but also have split the cytoplasm from the egg. With SCNT clones, a very different process takes place (Campbell et al. 1996). The egg [from which the nucleus has been removed] comes from one animal, the nuclear material comes from a somatic cell from another animal. This somatic cell is usually fused with the enucleated egg, and then is stimulated electrically or biochemically, while the resulting embryo, if it starts to grow, is then transplanted into the womb of a third animals which acts as the surrogate mother. Thus, a clone of an existing animal will not share the same egg cytoplasm as the original animal, and, while it might share the genes of the original animal, the fact that a nucleus from a somatic cell has been used means that the genes in the somatic cell are subtly different that genes from a fertilized egg. As the FDA notes, the genes in somatic cells need to be reprogrammed so that they are more like fertilized cells. Indeed, research has suggested that, for proper development to occur, a donor nucleus must undergo a reversal of differentiation and a genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming (Riek et al. 2001). Difficulties in this process are believed to be the cause of the high rate of birth defects, and other health problems, in clones. While the FDA acts like a lot is known about epigenetic reprogramming, the reality is that, some ten years after Dolly, there is still a lot that is not know about epigenetic reprogramming which helps explain why the vast majority (e.g. 95%) of cloned embryos do not survive to adulthood.

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 16

- The notion that cloning poses “no unique risks” compared with other artificial reproductive technologies is highly misleading. First, by focusing only on whether or not “unique risks” occur with cloning ignores the importance of quantitative differences in risks between cloning and other reproductive techniques. Over 90% of cloning attempts end in dead animals.

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 17

- A number of researchers have noticed similarities between some of the mitochondrial depletion diseases in humans and some of the abnormalities seen in SCNT and hypothesize that aberrant nuclear-mitochondrial interactions in SCNTs could be responsible for some of these abnormalities. A research team in Germany found that “A survey of perinatal clinical data from human subjects with deficient mitochondrial respiratory chain activity has revealed a plethora of phenotypes that have striking similarities with abnormalities commonly encountered in SCNT fetuses and offspring. We discuss the limited experimental data on nuclear-mitochondrial interaction effects in SCNT and explore the potential effects in the context of new findings about the biology of mitochondria” (Hiendleder et al. 2005: 69). Researchers in the United Kingdom have suggested that potential overpopulation of mitochondria could lead to the large offspring syndrome often seen in SCNT cow clones and call for more work in this area: “a cytoplasm over-populated with mitochondria would lead to cellular expansion that might be indicative of the reported large-offspring syndromes. This under-researched area of investigation could provide clear answers to some of the developmental abnormalities witnessed in NT offspring and aborted feotuses, whether mediated through failure of somatic cell reprogramming or independently” (St John et al. 2004: 638-639).

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 20

- In sum, there is a unique risk posed by SCNT clones that is not posed by other ARTs (artificial reproductive technologies): the potential for aberrant nuclearmitochondrial interactions. Embryos created via SCNT embryos differ from those created by other ARTs in two ways: they may be heteroplasmic (e.g. contain mtDNA from two sources) and nuclear-encoded mitochondrial DNA transcription and translation factors persist in SCNT, but not IVF, embryos.

- Michael Hansen, "Comments of Consumers Union to US Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Animal Cloning Risk Assessment", Consumers Union, (2007-04-27), p. 21

Dialogue

[edit]- Why do we need therapeutic cloning? As a layman, several important reasons come to mind. One, implantation of human embryonic stem cells is not safe unless they contain the patient's own DNA. Two, efforts, to repair central nervous system disorders may need to recapitulate the process of fetal development, and that could only be accomplished by human embryonic stem cells. Three, therapeutic cloning is done without fertilizing an egg. It can be strictly regulated. If we also enforce an absolute ban on reproductive cloning, we will not slide down the dreaded slippery slope into moral and ethical chaos.

Any powerful new technology comes with the possibility for abuse. But when we decide that the benefit to society is worth the risk, we take every possible precaution and go forward.

The unfertilized eggs that will be used for nucleus transplantation will never leave the laboratory and will never be implanted in a womb. But if we do not make this research legal, if we do not use Government funding and oversight, it will happen privately, dangerous unregulated and uncontrolled.- Christopher Reeve, Testimony in favor of funding human cloning experiments [S. 1758 Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2001], (Senate - March 5, 2002)

- In response to something that Dr. Frist said, I need to object, and that is that, Senator, you insist on separating therapeutic cloning and embryonic stem cells. However, in my own case, I require re-myelination of nerves. That means replacing the conductive coat of fat, myelin, that allows electricity to come down, currents from the brain to the central nervous system for function. At the moment, only embryonic stem cells have the potential to do that, and experiments are being done now in larger animals demonstrating that.

In fact, a scientist at Washington University, Dr. John McDonald, whom I have been working with says that there is no way he would inject stem cells without being able to use my own DNA for safety reasons. So without the ability to use my own DNA, without that somatic cell transfer, I am out of luck.

The other thing is to please remember that therapeutic cloning, nucleus transplantation, is done with unfertilized eggs. You keep referring to destroying an embryo. I think that destroying an embryo is what happens when the leftovers from fertility clinics are thrown out. We can agree that they go to the garbage routinely. But to say that an unfertilized egg has the same status, I believe is incorrect, and I think that this is the line of research that holds so much promise and can also get us around the ethical quandary that we keep putting ourselves in. We are talking about an unfertilized egg that will never leave the lab, that will never be implanted in a womb, and that can be regulated. And it is crucial for research.- Christopher Reeve, Tes-timony in favor of funding human cloning experiments [S. 1758 Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2001], (Senate - March 5, 2002)

- Drucker: You know, we shouldn't forget that not long ago, there were almost no more fish left in the ocean and half the world's population faced the threat of hunger. Cloning technology turned that around. Extremists won't admit they'd rather people went hungry than eat cloned fish, so they yell about human cloning.

- Reporter: Do you think human cloning laws should be changed?

- Drucker: Suppose a ten-year-old boy is in the hospital, dying of liver cancer. Thanks to Dr. Weir's work, we can save that boy. In the next bed lies another ten-year-old boy whose parents love him just as much, only he has an inoperable brain tumor. You cannot clone a brain. The only way to save him would be to clone the whole person. How do you tell that boy's parents that we can save the first boy, but the research that would have saved their son wasn't done, because of a law passed by frightened politicians a decade ago?

- Cormac and Marianne Wibberley, The 6th Day, (November 16, 2000).

“Cloning: The Debate”, New York Academy of Sciences, (May 20, 2002)

[edit]

- Stewart Newman: If embryo cloning is permitted, within a few years frustration over lack of progress in producing safe and effective therapeutics from (?) embryo stem cells will lead to calls to permit harvesting of embryo germ cells from two to three month clonal embryos, and we may find ourselves here again.

- p.2

- Christopher Reeve: If nucleus transplantation, aka therapeutic cloning, is banned, it will be a tremendous setback for science, and it will be indefinitely ... it will indefinitely prolong the suffering of hundreds of millions around the world, who are afflicted with wide variety of diseases and disabilities.

- p.2

- Rudolf Jaenisch: The technique of therapeutic cloning combines nuclear cloning and embryonic stem cell research with the goal of creating a customized stem cell line for a needy patient. For instance, if anyone of you is severely diabetic, one would take, for example, a skin cell, remove its nucleus and transfer the nucleus into a human egg from which its own nucleus has been removed. The nucleus would be injected then ... would be ... and then the nucleus of this cell is exposed to signals of the egg, it reverts to its embryonic state, and your skin cell begins to re-express those things that it expressed when it was an embryo. Whether the cell that results from this is a new embryo or a skin cell rejuvenated is as much a question of philosophy as of science. The cloned cells can be grown in the petri dish and can be induced to differentiate to insulin producing cells and implanted into you back. They will not be rejected because they are from your own body. So this is one possible scenario, medical scenario, there are many others, including treatment for Parkinson, blood diseases, liver diseases and so on.

- p.3

- Rudolf Jaenisch: In vitro fertilization, the embryos has a unique combination of genes that has not existed before, and it has a high potential to develop into a normal baby, healthy baby when implanted. In therapeutic cloning, the embryo has identical combination of genes as a donor, has no conception. Therefore the cloned embryo does not represent the creation of new life, but rather reprogramming and rejuvenation of an existing cell from your body. One could argue it's a special form of transplantation. The cloned embryo has a very low, exceedingly low potential to ever develop into a normal baby, because of the overwhelming problems which is associated with reproductive cloning.

So the generation of embryonic stem cells from cloned (Inaudible) for the purpose of therapeutic cloning would appear to pose fewer ethical problems than the generation of embryonic stem cells from in vitro fertilized embryos, and the majority in this country certainly supports that.- p.4

- James Kelly: Complex technical obstacles stand in the way of human cloning through somatic nuclear transfer ever being medically used in humans. These obstacles include short and long term genetic mutations, tumor formation and unexpectedly tissue rejection. In addition, the cloning process is very inefficient in itself, often requiring a hundred women’s eggs to create an embryo able to yield stem cells. Because of these roadblocks, scientists expect it will take decades before cloning will have clinical uses, if ever, regardless of whether stem cells from cloning ... cloned embryos can show results in the lab. And leading scientists in the embryonic stem cell field, including James Thompson, have admitted that the cost of cloning based therapy would be astronomical. Others have simply said that no one can afford it.

If human cloning research is allowed to move forward, these obstacles will need to be overcome for each of cloning's potential medical uses. This will unavoidably necessitate diverting crucial resources from other avenues that have already proven their ability to safely address the conditions that cloning has only hoped to address in the distant future. In humans, adult stem cells have successfully been used to treat multiple sclerosis, diabetes, certain forms of cancer, stroke, Parkinson's disease, and immune deficiency syndrome. They're in clinical trial for spinal cord injury, heart disease, and ALS. More work certainly needs to be done to refine and expand their uses and to improve their performance, but refining, expanding and improving are far cries from embarking on a new, highly problematic research, with little hope of leading to medically available treatments. In fact, such a trade off would be madness.

Yet we're being told that cloning is our brightest hope to cure disability and disease. Many sick, disabled and dying people have embraced this message in the name of desperation and trusting hope.- pp.4-5

- Stuart Newman: I'm here to argue that not only is full term cloning a bad idea, as Dr.Jaenisch forcefully pointed out, but that so-called therapeutic cloning, that is, nuclear transfer to make stem cells, is also in the long run going to be a bad idea. And I want to emphasize that my views on this don't arise from any notion of the sanctity of the embryo or any religious ideas or anything like that. But I do feel that there's probably nobody in this room that won't have some point in which they say, this is unacceptable. So for example, if a clonal fetus is allowed to develop to seven months, in order to harvest cells, this might be unacceptable to more people than growing clonal embryos for only seven days or 14 days.

Probably everybody in this room would say, we certainly don't want to make full term babies for the purpose of transplanting tissue. Probably everybody would object to that. What I would like to convey to you is that the logic of the science and medicine is leading us in that direction. Not because anybody is motivated to do that per se; specifically, I don't think any of the scientists involved are motivated to do that, but there are all sorts of pressures, patient pressures, commercial pressures--and the patient pressures I believe are very genuine, authentic and must be satisfied in some way, so I'm not arguing that there shouldn't be patient pressures--but there will be pressures to bring us to the point. As was quoted from my Senate testimony, there are, in fact, stem cells that can be harvested from two month old embryos. These are called “embryo germ cells.”

So if clonal embryos were produced, and it became possible, as some scientists are attempting, to grow the embryo for two months rather than just for seven days or 14 days, it would be possible to harvest these embryo germ cells. Now, why would you want to do that? John Gearhart at Johns Hopkins has worked on those cells, and has shown that they are apparently as versatile as embryo stem cells from the early petri dish cultures, but they don't have the same propensity to cause cancer when transplanted into adult animals. Now that's a very important motivation for harvesting these later stem cells.- p.6

- Stuart Newman: Dr. Jaenisch mentioned the scenario of treating diabetics with embryo stem cells. But one of the problems in Type 1 diabetics is that they reject their own insulin producing cells. So even if you could clone that person into a clonal embryo, grow up islet cells and transplant them back into the diabetic, the person's immune system would still reject those cells. So you would have to find some way to immune-suppress the diabetic patients anyway, so as to treat them with embryo stem cells. I think that the American people are very optimistic and only want to hear about the promises, and don't want to hear about the downside. I just point out that in a very recent paper of Dr. Jaenisch 's that he spoke about, where he showed the proof of principle of using stem cells and transplanting differentiated bone marrow cells back into the mouse with the immune deficiency, there was another experiment as well where they corrected the genetic defect in the embryo stem cells. The embryo stem cells were used to produce a full term clone of the original genetically defective mouse, but with the genetic condition corrected. They now had a genetic twin of the original mouse with the corrected gene, and were then able to use bone marrow from that corrected mouse to treat the original mice.

Now here's a scenario for which many people would say, “great!” People are already having new children to provide bone marrow for children with genetic conditions. If the public was aware that now you could clone your sick child and use the bone marrow from the new child--whom you'll love like your old child, of course--and transfer that bone marrow back into your sick child, huge sectors of the public would find that acceptable. And this is what I mean when I say that we're on a track where we're coming closer and closer to full term cloning, by way of all sorts of intermediate stages. And it's not that there aren't people already advocating this.- pp.6-7

- Stuart Newman: Dr. Jaenisch has argued very strongly against full term cloning, and as developmental biologists he and I know the reasons that this should never be attempted. But there are many people out there, bioethicists who are saying, well, we take risks every day in our lives. If it's risky to have a cloned child, well, so be it. We go out and drive our cars, right? We breathe the air. So let's take these risks. And this is crazy. But apparently otherwise responsible bioethicists are advocating this. And to my mind, this is going to happen; it's virtually inevitable unless legal restrictions are put in place. I disagree with some of the very punitive criminalization of scientific activities and therapies from abroad in the proposed Brownback legislation. I think something has to be done about that. But on the point of prohibiting embryo cloning, I think that it must be done, or we'll all wind up in a place where we don't want to be.

- p.7

- Christopher Reeve: I work with Dr. John McDonald at Washington University in St. Louis, and he is a very knowledgeable researcher on (Inaudible) stem cells, and a few years ago he said to me that in order to cure my particular condition, which is demyelination of nerves in a very small area of the spinal cord, right at the second cervical vertebrae, that if you imagine the rubber coating around a wire that allows conductivity of electricity, the same thing as with nerves, myelin is like that rubber coating. It's a fatty substance that if it comes off of the nerves, then signals do not go from the brain down to the spinal cord as required. However, it is possible, and he's demonstrated this as graphic(?) as possible, to re-myelinate.

Now, a few years ago, he said, we would be willing to inject human embryonic stem cells into you and hope for the best. But hoping for the best is a very dangerous proposition for people with spinal cord injuries because our spinal cord injury affects every organ in the body, and the most serious side effect is that it severely compromises the immune system, so spinal cords patients, particularly with high level injuries like mine, are prone first to pneumonia, which I've had at least five times since my injury, many patients often die from that. Also, it compromises the cardiovascular system, compromises the digestive tract, the ... your whole bowel-bladder-sexual function, skin integrity and also bone density, so that osteoporosis becomes a very ... a very critical factor.

So literally he said to me that the immunosuppression that would be required just to inject 30million human embryonic stem cells from an anonymous donor might kill me. And now, he would be unwilling as a doctor, because of the ethics involved that a doctor is ethically bound to give his patients the best possible treatment, he would not inject me with embryonic stemcells unless we go the other route, which is therapeutic cloning- taking an egg, removing the nucleus, taking DNA from my skin and deriving stem cells from that, which would be injected in a manner that would probably not be rejected by my immune system.

So my future, and others would agree, many scientists would agree, my future, in terms of being able to recover will depend on some way of delivering stem cells without compromising my immune system and therapeutic cloning, which would use my DNA is the best hope.- p.8

- Antonio Regalado: I'm Antonio Regalado, from the Wall Street Journal, I just had an informational question for Mr.Reeve. You said that your doctor, Dr. McDonald, would not implant embryonic ... human embryonic stem cells into you unless that you went through the therapeutic cloning ... that that was your best chance of being able to recover potentially. Have you actually pursued that line of research directly with your own cells? Any attempts to transform them?

- p.10

- Christopher Reeve: No, you have to understand that therapeutic cloning is a very nascent technology that's not ready for use in humans. But knowing that it will not . . . provided our scientists are allowed to go ahead with the research, it really shouldn't take that long before they're ready for humans. However, knowing that there is a better technology out there than just using embryonic stemcells, he as a doctor feels, given the immune rejection problem for people with spinal cord injuries, he's not going to go ahead, as he had planned to. There was a plan to actually use embryonic stem cells as soon as it would be allowed by the FDA. He is not going to do that until therapeutic cloning gets to the point where it could be applied to humans.

And I just want to make one other very quick comment and that is in England, just a month ago, Dr. Ann Bishop, who works with the tissue engineering corporation over there, was able to take mouse embryonic stem cells that derived . . . had been made obviously therapeutic cloning, and they turned those cells into tissue that is applied to the lungs, to deficient cell types or cell tissues in the lungs, and said, have already reported, I guess it's public knowledge, that they feel they are now ready to do it in humans, so the idea that it would be decades before you could get to human application, I think that is one example I'm giving you right now of the fact that that's not true. I can give you another example. Doctor Oswald Stewart, of the Reeve Research Center, UC Irvine has said that you could probably get to the use of therapeutic cloning in humans within about three to five years. So I absolutely dispute the time line that's been put up before.- pp.10-11

- Apporva Mandavilli: I'm Apporva Mandavilli, from Biomednet news. There is this difference between the U.S. and U.K. as far as regulation, so what's to stop the average patient from just getting on a plane and going to the U.K. and getting the treatment they need? And is there a concern among the scientific community that this is going to set U.S. research back?

- Craig Venter: Dr. Jaenisch?

- Rudolf Jaenisch: If you will do this, according to the Weldon bill which was passed last year by the House, you will be arrested on the return at the airport, and put in jail and fined because you're carrying cells derived from a cloned embryo in you. That's the bill.

- p.11

- James Kelly: This is a topic that I discussed with Dr. Young of Rutgers. Dr. Young is in favor of therapeutic cloning, and he pointed out to me on the Internet, his Internet forum, speaking on the moral issues, he said that why ban cloning in the United States when somebody might be able to get on a plane, fly to England, whatever, if it was available, if it was a treatment, and be cloned? The only way we could find out whether or not they actually had such a therapy upon their return would be to do a DNA check of all returning people to the United States, which is ... of course is not going to happen.

My response to Dr. Young and here again, my reasons for even looking into this in the first place and for opposing cloning on the scientific reasons I've mentioned in my opening five minutes, my response to Dr. Young is, people can get on a plane, and they can fly to other countries. NBC mentioned the Eastern European countries as one where they might be able to engage in child prostitution. Does that mean that we should make child prostitution legal in the United States? Because if cloning is going to be banned, it's going to be banned because of these scientific reasons. It's going to be banned for moral reasons. That's why the ... that's why Senator Brownback proposed the legislation. And if it's banned for moral reasons, we shouldn't change our moral perspective in the United States simply because somebody else somewhere else in the world says something is moral that we in the United States have decided is immoral.- p.11

- Christopher Reeve: On the other hand, you have to understand that our allies are not rogue nations. The U.K., Australia, Canada, Singapore, Israel, India, these are just some of the countries that have already passed therapeutic cloning. In fact, England passed it twice. The House of Lords considered it, passed it, the pro-life groups objected to it, they took time to listen to those groups and then they passed it a second time. And therapeutic cloning is allowed with strict government oversight. And to say that those countries are less moral than we are, I think is hubris on our part that's out of control.

- p.11

- Stuart Newman: It's kind of interesting how the ways of thinking about this evolves. I agree that these cloned animals are not normal. Dr. Jaenisch 's work has given ample proof of this. Moreover, the tetraploid embryos are also abnormal, and Dr. Jaenisch said before that in making clonal embryos to generate these stem cells you don't make a new individual, because it's an individual that is genetically precedented, that is, it's genetically derived from a prototype. But back in 1997, when Dolly was first cloned, although there were people that said we should clone humans and people that said we shouldn't clone humans, it seemed like everybody agreed that if you do clone a human, it'll be a human. But now, people are saying, bioethicists, and I just heard Dr. Jaenisch say it, that when you make these clones by nuclear transfer, you're making something that's like ... more like a manufactured item. It's not really anew individual. Therefore, you could potentially do anything you want with it. If you wanted to grow it up to an abnormal full term whatever, it wouldn't be a person. As Dr. Jaenisch said, you're not creating a new individual by doing this, so you have something that you are now at liberty to do whatever you want with...

- Craig Venter: So why don't you define human for us, what's your definition of ... (Overlap)

- Stuart Newman: I don't have a definition, but I'm saying that whatever results from this process is at least quasi-human, and I'm uneasy about people patenting it. The University of Missouri just took out a patent on cloning mammals, in which they didn't specifically exclude humans from this cloning process. People are going to own these quasi-human entities, and I think it's something we should be concerned about. (Overlap)

- Craig Venter: Is a HeLa cell a quasi-human entity?

- Stuart Newman: No, no, we're talking about developing embryos.

- Craig Venter: But a HeLa cell has the genetic information from the donor. Why is that ...

- Stuart Newman: I don't think ...(Overlap)

- Craig Venter:...not a quasi-human entity under your definition?

- Stuart Newman: Well, I think that people can make that distinction.

- pp.13-14

- James Kelly: The Justice Department just testified to the House, and in their testimony, they specifically said that they can't tell the difference from the cloning process and the reproductive process as far as the embryos being implanted. And they specifically said that they would not be able to regulate reproductive cloning. Separate from therapeutic cloning.

- p.14

- Craig Venter:... the ultimate end of the slippery slope argument gets back to reproductive cloning instead of therapeutic cloning, right? That's the slippery slope that's held in front of all of us as the big evil.

- Stuart Newman: It's reproductive cloning, but it's also all these stages along the way. The two month, the six month, the nine month fetus. Wherever you decide the line should be drawn it will be eventually be crossed.

- p.17

- Christopher Reeve: I believe, throughout history, there has been common agreement in societies around the world that the life results because of the union of male and female. Whether it's done in a test tube, or whether it's done through intercourse. And fertilized embryos in clinics are still the union, result of the union of male and female. Therapeutic cloning takes an egg that is not fertilized, and is left in the cellular stage, in the very early stages, about three to five, seven days, then the nucleus is removed and the DNA from a patient. Either male or female can be put into it. Now, that is an aberrant life form. If you were to take it further and implant it, then only insane people would want to do that, in my opinion. But considering the fact that they're talking ... you're talking about the difference of life as we've understood it for hundreds of thousands of years, versus a collection of cells that will never become a human being, and I don't even believe deserves a status of the word embryo. It could be called a pseudo-embryo, it could be called, you know, some other name should come up from it, because just like test tube babies scared people before, the buzzword embryo scares people today. Cloning scares people today, but this is simply a manipulation of cells that are not equivalent to life as we've always known it.

- p.19