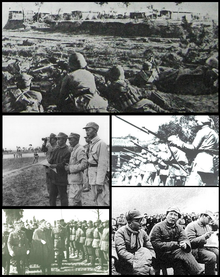

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a civil war in China fought between the Kuomintang (KMT)-led government of the Republic of China (ROC) and forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) lasting intermittently between 1927 and 1949.

The war is generally divided into two phases with an interlude: from August 1927 to 1937, the KMT-CCP Alliance collapsed during the Northern Expedition, and the Nationalists controlled most of China. From 1937 to 1945, hostilities were put on hold, and the Second United Front fought the Japanese invasion of China with eventual help from the Allies of World War II. The civil war resumed with the Japanese defeat, and the CCP gained the upper hand in the final phase of the war from 1945 to 1949, generally referred to as the Chinese Communist Revolution.

The Communists gained control of mainland China and established the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, forcing the leadership of the Republic of China to retreat to the island of Taiwan. Starting in the 1950s, a lasting political and military standoff between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait has ensued, with the ROC in Taiwan and the PRC in mainland China both officially claiming to be the legitimate government of all China. After the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, both tacitly ceased fire in 1979, however, no armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed.

Quotes

[edit]

A

[edit]B

[edit]- Despite American support, the Nationalists were defeated anew after World War Two: by the Communists in the Chinese Civil War. This defeat would have been less likely, bar for the war. Prior to the Japanese attack on China, the Communists had been in a vulnerable position in their conflict with the Nationalists. As a result of repeated and increasingly successful Nationalist attacks from 1930, the Communists, in 1934, had abandoned their base in Jiangxi and, in the Long March, had moved in 1935 to a more remote rural power base in northern Shanxi. Funded and provided with arms by Stalin, Mao had become a factor in the complicated negotiations of power in China. Following the Japanese attack, the Communists benefited from having become, during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the dominant anti-Japanese force in northern China and from the war having weakened the Nationalists.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- The Chinese Civil War was the largest conflict, in terms of number of combatants and area fought over, since World War Two, and it proves an instructive counterpoint to the latter, indicating the difficulty of drawing clear lessons from the conflicts of the 1940s. Nevertheless, there has been far less scholarship on the Chinese Civil War, and much of the work published on it has reflected ideological bias, notably being used to support the legitimacy of the Communist regime.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- In China, technology and the quantity of materiel did not triumph, as the Communists were inferior to the Nationalists in weaponry, and, in particular, lacked air and sea power. However, their strategic conceptions, operational planning and execution, army morale, and political leadership, proved superior, and they were able to make the transfer from guerrilla warfare to large-scale conventional operations; from denying their opponents control over territory to seizing and securing it. Mao’s party and army possessed unitary command and lacked a multi-party consensus model. The Nationalist cause, in contrast, was weakened by poor and highly divided leadership, inept strategy, and, as the war went badly, poor morale. In addition, corruption and inflation greatly affected civilian support. Indeed, the China White Paper published by the State Department in 1950 blamed the Nationalists’ failure on their own incompetence and corruption.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- There was strong pressure in the USA to intervene on the Nationalist side, particularly from the Republicans, who repeatedly raised the charge of weakness toward Communism. Longstanding American interest in China had been strengthened in World War Two, not least with a large-scale expansion of the economy of the Pacific states. Moreover, the south and west became more important in economic and demographic terms during the post-war ‘baby boom’ and there was to be a cultural shift toward the Pacific coast. All these factors contributed to enhanced interest in East Asia. Nevertheless, the Truman government decided not to intervene in China. It took a lesser role than in the Greek Civil War, which was a more containable conflict and one more propitious for Western intervention. There was also great distrust of Jiang Jieshi, the Nationalist leader. As a result, the Republicans organised a witch hunt of those who had allegedly betrayed China.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- In 1948, as the Communists switched to conventional, but mobile, operations, the Nationalist forces in Manchuria were isolated and then destroyed, and the Communists regained Shensi and conquered much of China north of the Yellow River. Communist victory in Manchuria led to a crucial shift in advantage, and was followed by the rapid collapse of the Nationalists the following year. The Communists made major gains of matérial in Manchuria, and it also served as a base for raising supplies for operations elsewhere. After overrunning Manchuria, the Communists focused on the large Nationalist concentration in the Suchow-Kaifeng region. In the Huai Hai campaign, beginning on 6 November 1948, each side committed about 600,000 men. The Nationalists suffered from poor generalship, including insufficient coordination of units, and inadequate use of air support, and were also hit by defections. An important factor in many civil wars, defections from the Nationalists proved highly significant in the latter stages of the Chinese Civil War. Much of the Nationalist force was encircled thanks to effective Communist envelopment methods, and, in December 1948 and January 1949, it collapsed due to defections and combat losses.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- Jiang Jieshi resigned as President on 21 January 1949, and the Communists captured Beijing the following day. They responded to the new President’s offer of negotiation by demanding unconditional surrender, and the war continued. The Communist victories that winter had opened the way to advances further south, not least by enabling them to build up resources. The Communists crossed the Yangzi River on 20 April 1949, and the rapid overrunning of much of southern China over the following six months testified not only to the potential speed of operations, but also to the impact of success in winning over support. Nanjing fell on 22 April, and Shanghai on 27 May, and the Communists pressed on to capture rapidly the other major centres. Fleeing the mainland, Jiang Jieshi took refuge on the island of Formosa (Taiwan), which China had regained from Japan after the end of World War Two. It was protected by the limited aerial and naval capability of the Communists and, eventually, by American naval power. However, until he intervened in Korea in 1950, Mao Zedong prepared for an invasion of Formosa, creating an air force to that end. Jiang, in turn, used Formosa and the other offshore islands he still controlled as a base for raids on the mainland. Meanwhile, in the spring of 1950, the island of Hainan and, in 1950–1, Tibet were conquered by the Communists, the capital of Tibet, Lhasa, being occupied on 7 October 1950. The CIA subsequently backed rebellion in Tibet, notably by Khampa rebels. The new strategic order in Asia was underlined in January 1950 when China and the Soviet Union signed a mutual security agreement. Mao was in Moscow for two weeks, an unheard of amount of time for a head of state: Stalin would not see Mao for a while, insulting him. Tension between the two regimes was there from the start.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- The Chinese Civil War was not a simple struggle between Communists and anti-Communists. It drew on a number of strands in Chinese history, including regional rivalries and the issues of military control. Moreover, the success of the Nationalists’ Northern Campaign in the late 1920s, when, from a base in the south, they gained control over all the country bar Manchuria, indicated that Communism was not itself necessary to deliver such a military verdict. Nevertheless, the Communist success in 1946–50 was more complete, not only because it included Manchuria and Tibet, but also because it was not dependent, as that of the Nationalists (or indeed the Manchu in the 1640s–50s) had been, on co-operation with warlords. Moreover, as a result of Mao, the nationalism and nation-state building seen in China earlier in the century was linked to the Cold War.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

C

[edit]- At the end of World War II which brought about the defeat of the Nazi aggressors, our nation and our people achieved their long-cherished desire for liberty at home and equality in the community of nations. Before long, however, the people on the Chinese mainland were robbed of their personal property, separated from their families and relatives, deprived of their cultural and historical heritage, and denied their human and individual dignity. They have been forced to serve as Communist tools of aggression for the enslavement of yet other peoples.

- Chiang Kai-shek, Inaugural Speech (1966)

D

[edit]- The Chinese Communist Party refers to its victory in 1949 as a ‘liberation’. The term brings to mind jubilant crowds taking to the streets to celebrate their newly won freedom, but in China the story of liberation and the revolution that followed is not one of peace, liberty and justice. It is first and foremost a history of calculated terror and systematic violence. The Second World War in China had been a bloody affair, but the civil war from 1945 to 1949 also claimed hundreds of thousands of civilian lives – not counting military casualties. As the communists tried to wrest the country from Chiang Kai-shek and the nationalists, they laid siege to one city after another, starving them into submission.

- Frank Dikotter, The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution 1945–1957 (2013), p. 5

E

[edit]F

[edit]- The revolutionary dimensions of Mao’s victory were not well understood at the time and are still contested. Neither a grievous political defeat for the United States nor a great triumph for the USSR, the establishment of communist rule in China exposed the limits of the Superpowers’ agility and skill. Locked in their rivalry over Europe in 1947–1948, both had failed to deal adroitly with the rapid deterioration of the Nationalist (Kuomintang) government and with the communists’ determination to prevail. In Washington, which was caught up in the close presidential campaign of 1948, the debate between the ardent proponents of military support for Chiang and the equally passionate decriers of his government’s corruption and ineptitude produced a $400 million aid appropriation but also a paralyzing fatalism over the US role in China’s future, particularly given the political impossibility of armed intervention. Similarly, in Moscow, the fears of US intervention and of a feisty Chinese Tito as well as the advantages of a weak and divided China that would preserve the Yalta gains had to be weighed against the ideological benefits of obtaining a huge Asian satellite. Stalin’s capricious gestures in 1948 were the result: a mediation offer that annoyed Washington and infuriated Mao and the delay in inviting the communist leader to Moscow, but also the intense communications between the two parties, the procommunist pronouncements later that year, and the stepped-up arms deliveries and diplomatic contacts in 1949.

- Carole C. Fink, The Cold War: An International History (2017), p. 75

G

[edit]- A second but simultaneous expansion of the Cold War occurred in East Asia, where on October 1, 1949—a week after Truman's announcement of the Soviet atomic bomb—a victorious Mao Zedong proclaimed the formation of the People's Republic of China. The celebration he staged in Beijing's Tiananmen Square marked the end of a civil war between the Chinese nationalists and the Chinese communists that had been going on for almost a quarter of a century. Mao's triumph surprised both Truman and Stalin: they had assumed that the nationalists, under their long-time leader Chiang Kai-shek, would continue to run China after World War II. Neither had anticipated the possibility that, within four years of Japan's surrender, the nationalists would be fleeing to the island of Taiwan, and the communists would be preparing to govern the most populous nation in the world.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (2006), p. 36

H

[edit]I

[edit]K

[edit]L

[edit]M

[edit]- The situation in China was full of explosives, the handling of which required delicacy. Shortly before the actual surrender the Japanese withdrew their forces to the Yangtze Valley and to North China, where the Chinese Communists demanded that they receive the Japanese surrender. General Okamura, commander of the North China Area Army, refused, but on 17 August let it be known that he would surrender to Chiang Kai-shek. Unfortunately, the Generalissimo and his Nationalist armies were far distant, in southwest China. A Japanese puppet Chinese government with its own "Peace Preservation Troops" further complicated matters. And although the United States was willing to assist the Nationalist government to reestablish control over Chinese territory, it was fearful of being involved in a civil war.

- Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume XV: Supplement and General Index (1962), Boston: Little, Brown & Company, p. 4

N

[edit]O

[edit]P

[edit]Q

[edit]R

[edit]S

[edit]- In their native countries, Roosevelt and Churchill are regarded as examples of wise statesmen. But we, during our jail conversations, were astonished by their constant shortsightedness and even stupidity. How could they, retreating gradually from 1941 to 1945, leave Eastern Europe without any guarantees of independence? How could they abandon the large territories of Saxony and Thuringia in return for such a ridiculous toy as the four-zoned Berlin that, moreover, was later to become their Achille’s heel? And what kind of military or political purpose did they see in giving away hundreds of thousands of armed Soviet citizens (who were unwilling to surrender, whatever the terms) for Stalin to have them killed? It is said that by doing this, that they secured the imminent participation of Stalin in the war against Japan. Already armed with the Atomic bomb, they did pay for Stalin so that he wouldn’t refuse to occupy Manchuria to help Mao Zedong to gain power in China and Kim Il Sung, to get half of Korea!… Oh, misery of political calculation! When later Mikolajczyk was expelled, when the end of Beneš and Masaryk came, Berlin was blocked, Budapest was in flames and turned silent, when ruins fumed in Korea and when the conservatives fled from Suez – didn’t really some of those who had a better memory, recall for instance the episode of giving away the Cossacks?

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago Part 1, Chapter 6

T

[edit]- Nevertheless, the Chinese Government and people are still laboring under the double and interrelated burden of civil war and a rapidly deteriorating economy. The strains placed upon the country by eight years of war, and the Japanese occupation and blockade have been increased by internal strife at the very time that reconstruction efforts should be under way. The wartime damage to transport and productive facilities has been greatly accentuated by the continued obstruction and destruction of vital communications by the Communist forces. The civil warfare has further impeded recovery by forcing upon the Government heavy expenditures which greatly exceed revenues. Continual issuances of currency to meet these expenditures have produced drastic inflation with its attendant disruption of normal commercial operations. Under these circumstances China's foreign exchange holdings have been so reduced that it will soon be impossible for China to meet the cost of essential imports. Without such imports, industrial activity would diminish and the rate of economic deterioration would be sharply increased.

U

[edit]V

[edit]W

[edit]X

[edit]Y

[edit]Z

[edit]- 中国人民从中国解放区和国民党统治区,获得了明显的比较。

难道还不明显吗?两条路线,人民战争的路线和反对人民战争的消极抗日的路线,其结果:一条是胜利的,即使处在中国解放区这种环境恶劣和毫无外援的地位;另一条是失败的,即使处在国民党统治区这种极端有利和取得外国接济的地位。

国民党政府把自己的失败归咎于缺乏武器。但是试问:缺乏武器的是国民党的军队呢,还是解放区的军队?中国解放区的军队是中国军队中武器最缺乏的军队,他们只能从敌人手里夺取武器和在最恶劣条件下自己制造武器。

国民党中央系军队的武器,不是比起地方系军队来要好得多吗?但是比起战斗力来,中央系却多数劣于地方系。

国民党拥有广大的人力资源,但是在它的错误的兵役政策下,人力补充却极端困难。中国解放区处在被敌人分割和战斗频繁的情况之下,因为普遍实施了适合人民需要的民兵和自卫军制度,又防止了对于人力资源的滥用和浪费,人力动员却可以源源不竭。

国民党拥有粮食丰富的广大地区,人民每年供给它七千万至一万万市担的粮食,但是大部分被经手人员中饱了,致使国民党的军队经常缺乏粮食,士兵饿得面黄肌瘦。中国解放区的主要部分隔在敌后,遭受敌人烧杀抢“三光”政策的摧残,其中有些是像陕北这样贫瘠的区域,但是却能用自己动手、发展农业生产的方法,很好地解决了粮食问题。

国民党区域经济危机极端严重,工业大部分破产了,连布匹这样的日用品也要从美国运来。中国解放区却能用发展工业的方法,自己解决布匹和其他日用品的需要。

在国民党区域,工人、农民、店员、公务人员、知识分子以及文化工作者,生活痛苦,达于极点。中国解放区的全体人民都有饭吃,有衣穿,有事做。

利用抗战发国难财,官吏即商人,贪污成风,廉耻扫地,这是国民党区域的特色之一。艰苦奋斗,以身作则,工作之外,还要生产,奖励廉洁,禁绝贪污,这是中国解放区的特色之一。

国民党区域剥夺人民的一切自由。中国解放区则给予人民以充分的自由。

国民党统治者面前摆着这些反常的状况,怪谁呢?怪别人,还是怪他们自己呢?怪外国缺少援助,还是怪国民党政府的独裁统治和腐败无能呢?这难道还不明白吗?- The Chinese people have come to see the sharp contrast between the Liberated Areas and the Kuomintang areas.

Are not the facts clear enough? Here are two lines, the line of a people's war and the line of passive resistance, which is against a people's war; one leads to victory even in the difficult conditions in China's Liberated Areas with their total lack of outside aid, and the other leads to defeat even in the extremely favourable conditions in the Kuomintang areas with foreign aid available.

The Kuomintang government attributes its failures to lack of arms.

Yet one may ask, which of the two are short of arms, the Kuomintang troops or the troops of the Liberated Areas? Of all China's forces, those of the Liberated Areas lack arms most acutely, their only weapons being those they capture from the enemy or manufacture under the most adverse conditions.

Is it not true that the forces directly under the Kuomintang central government are far better armed than the provincial troops? Yet in combat effectiveness most of the central forces are inferior to the provincial troops.

The Kuomintang commands vast reserves of manpower, yet its wrong recruiting policy makes manpower replenishment very difficult. Though cut off from each other by the enemy and engaged in constant fighting, China's Liberated Areas are able to mobilize inexhaustible manpower because the militia and self-defence corps system, which is well-adapted to the needs of the people, is applied everywhere, and because misuse and waste of manpower are avoided.

Although the Kuomintang controls vast areas abounding in grain and the people supply it with 70-100 million tan annually, its army is always short of food and its soldiers are emaciated because the greater part of the grain is embezzled by those through whose hands it passes. But although most of China's Liberated Areas, which are located in the enemy rear, have been devastated by the enemy's policy of "burn all, kill all, loot all", and although some regions like northern Shensi are very arid, we have successfully solved the grain problem through our own efforts by increasing agricultural production.

The Kuomintang areas are facing a very grave economic crisis; most industries are bankrupt, and even such necessities as cloth have to be imported from the United States. But China's Liberated Areas are able to meet their own needs in cloth and other necessities through the development of industry.

In the Kuomintang areas, the workers, peasants, shop assistants, government employees, intellectuals and cultural workers live in extreme misery. In the Liberated Areas all the people have food, clothing and work.

It is characteristic of the Kuomintang areas that, exploiting the national crisis for profiteering purposes, officials have concurrently become traders and habitual grafters without any sense of shame or decency. It is characteristic of China's Liberated Areas that, setting an example of plain living and hard work, the cadres take part in production in addition to their regular duties; honesty is held in high esteem while graft is strictly prohibited.

In the Kuomintang areas the people have no freedom at all. In China's Liberated Areas the people have full freedom.

Who is to blame for all the anomalies which confront the Kuomintang rulers? Are others to blame, or they themselves? Are foreign countries to blame for not giving them enough aid, or are the Kuomintang government's dictatorial rule, corruption and incompetence to blame? Isn't the answer obvious?- Mao Zedong, "On Coalition Government" (1945)

- The Chinese people have come to see the sharp contrast between the Liberated Areas and the Kuomintang areas.