Philippe Pétain

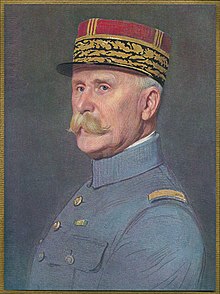

Appearance

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), generally known as Philippe Pétain, Marshal Pétain (Maréchal Pétain or The Lion of Verdun), was a French general who reached the military distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France (Chef de l'État Français), a collaborationist government established after France was defeated by Nazi Germany during World War II, from 1940 to 1944.

Quotes

[edit]- Neither Germany nor Italy have doubts. Our crisis is not a material crisis. We have lost faith in our destiny...We are like mariners without a pilot.

- Statement (April 1936), quoted in Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe 1914–1940 (1995), p. 182

- My country has been beaten and they are calling me back to make peace and sign an armistice...This is the work of 30 years of Marxism. They're calling me back to take charge of the nation.

- Remarks to Francisco Franco in Madrid, Spain, after the French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, recalled Pétain to France to raise morale against the German offensive during the Battle of France (c. 17 May 1940), quoted in Howard J. Langer, World War II: An Encyclopedia of Quotations (2013), p. 157

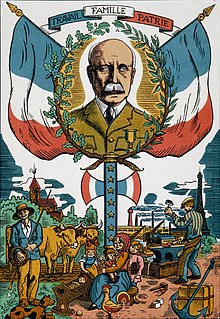

- La terre, elle, ne ment pas [The land, it does not lie].

- Speech (25 June 1940), quoted in Philippe Pétain, Discours aux Français, 17 juin 1940–20 août 1944 (1989), p. 66

- The only wealth you possess is your labour... France will become again what she should never have ceased to be—an essentially agricultural nation. Like the giant of mythology, she will recover all her strength by contact with the soil.

- Speech (August 1940), quoted in Pavlos Giannelia, 'France Returns to the Soil', Land and Freedom, Vol. XLI, No. 1 (January-February 1941), p. 23 and Eugen Weber, 'France', in Hans Rogger and Eugen Weber (eds.), The European Right: A Historical Profile (1966), p. 113.

Quotes about Pétain

[edit]

You regave us hope

The Fatherland will be reborn,

Marshal, Marshal,

Here we are! ~ André Montagard

- Le Maréchal-paysan [The Marshal-peasant].

- Nickname from the Vichy years, quoted in Amy S. Wyngaard, From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment (2004), p. 194 and Michael Tracy, Government and Agriculture in Western Europe, 1880–1988 (1989), p. 215

- [Pétain is France's] noblest and most humane soldier.

- Léon Blum, Le Populaire (3 March 1939), quoted in Robert Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 (1972), p. 35

- At seven o'clock [on 11 June 1940] we entered into conference. ... I urged the French Government to defend Paris. I emphasised the enormous absorbing power of the house-to-house defence of a great city upon an invading army. I recalled to Marshal Pétain the nights we had spent together in his train at Beauvais after the British Fifth Army disaster in 1918, and how he, as I put it, not mentioning Marshal Foch, had restored the situation. I also reminded him how Clemenceau had said: "I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris." The Marshal replied very quietly and with dignity that in those days he had a mass of manoeuvre of upwards of sixty divisions; now there was none. He mentioned that there were then sixty British divisions in the line. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event.

- Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume Two: Their Finest Hour [1949] (1951), p. 136

- [On 16 June 1940] Paul Reynaud was quite unable to overcome the unfavourable impression which the proposal of Anglo-French Union created. The defeatist section, led by Marshal Pétain, refused even to examine it. ... Weygand had convinced Pétain without much difficulty that England was lost. High French military authorities had advised: "In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken." To make a union with Great Britain was, according to Pétain, "fusion with a corpse".

- Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume Two: Their Finest Hour [1949] (1951), p. 182

- Pétain has always been an anti-British defeatist, and is now a dotard.

- Winston Churchill, memorandum (14 November 1940), quoted in The Second World War, Volume Two: Their Finest Hour [1949] (1951), p. 419

- I am entirely with the Marshall [Pétain], I see him as the Father of the patrie, blessed with a good sense verging on genius, and as a truly providential man.[1]

- Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange, from a letter written to Jacques Maritain (1941)

- Remember that France has always had two strings in its bow. In June 1940 it needed the Pétain "string" as much as the de Gaulle "string".

- Alleged remark by Charles de Gaulle to Colonel Rémy (December 1946), quoted in Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France since 1944 (1991), p. 34

- When Marshal Pétain offered to lay down French arms, he did not lay down arms that he still held, but ended a situation that every soldier could recognize as untenable. Only the blood-drenched dilettantism of a Mr. Churchill could fail to understand this or try to deny this in spite of better knowledge.

- Adolf Hitler, Reichstag speech (19 July 1940)

- Pétain never gave me the idea of a General whose personality or genius could lead huge armies to victory in a war where, at the right moment, a crashing attack was essential to defeat your formidable enemy. He was an able man and a good soldier. But he was essentially a Fabius Cunctator. He was careful and cautious even to the confines of timidity. His métier after the 1917 mutinies was that of a head nurse in a home for cases of shell-shock. ... Pétain did it well and successfully. There is no other French General who could have done it as well. ... Nevertheless, Foch's summing-up of him to Poincaré will be acknowledged by those who knew him as accurate and fair: “As second in command, carrying out orders, Pétain is perfect, but he shrinks from responsibility, and is not fitted for a Commander-in-Chief.” Both Poincaré and Clemenceau constantly complained of his pessimism. He was inclined to dwell on the gloomiest possibilities of a situation. Poincaré, in his Diary, said that in the German offensive Pétain was “defeatist.” He would have made an ineffective Commander-in-Chief for Allied Armies confronted with the problems of 1918.

- David Lloyd George, War Memoirs, Volume II (1938), p. 1751

- Marshal, here we are!

Before you, France's saviour,

We swear, we your people,

To serve and follow your feats.- Maréchal, nous voilà!

Devant toi, le sauveur de la France,<nr>Nous jurons, nous tes gars

De servir et de suivre tes pas. - André Montagard, first half of the chorus of "Maréchal, nous voilà!" (Marshal, here we are!", 1941), melody plagiarized from La Margoton du bataillon by Kasimierz Oberfeld. Dedicated to Pétain, the song was sometimes used by Vichy France as an alternative to "La Marseillaise."

- Maréchal, nous voilà!

- Marshal, here we are!

You regave us hope

The Fatherland will be reborn,

Marshal, Marshal,

Here we are!- Maréchal, nous voilà!

Tu nous as a redonné l'espérance

La patrie renaîtra,

Maréchal, Maréchal,

Nous voilà! - André Montagard, second half of the chorus of "Maréchal, nous voilà!" (Marshal, here we are!", 1941), melody plagiarized from La Margoton du bataillon by Kasimierz Oberfeld.

- Maréchal, nous voilà!

- Some already in power allied themselves with Hitler, including his chief ally, Benito Mussolini; Marshal Pétain (1856-1951; died in prison), the French premier who surrendered much of France to the Nazis; Pierre Laval (1883-1945; executed), former French prime minister who became leader of the Vichy government he helped the Germans establish; Marshal Ion Antonescu (1882-1946; executed), the vehemently anti-Semitic and anti-Russian conducator of Romania, who forced King Carol II to abdicate, supported the Germans on the Eastern Front, and oversaw the murder of 380,000 Jews and 10,000 Gypsies; Boris III, tsar of Bulgaria (1894-1943; possibly poisoned), who agreed to deport 13,000 Jews from recently reannexed territories though protected those in Bulgaria; Admiral Miklós Horthy (1868-1957), Regent of Hungary who collaborated with the Nazis through fear of communism, but eventually broke with Hitler; and generals Georgios Tsolakoglou (1886-1948), Konstantinos Logothetopoulos (1878-1961) and Ioannis Rallis (4878-1946), Nazi puppets in Greece.

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Monsters: History's Most Evil Men and Women (2009), pp. 258-259

- For some, Pétain was simply "le drapeau," a personification of abiding Old France: an erect old soldier of austere tastes, of Catholic peasant stock, marshal of France, member of the French Academy, returning from his modest country estate once more to rescue his country from the rabble. On the other side, Pétain seemed less threatening to republicans than many another senior officer. ... Only the irreverent young right had mocked Pétain without compunction in the 1930's. In the summer of 1940, therefore, Pétain fitted the national mood to perfection: internally, a substitute for politics and a barrier to revolution; externally, a victorious general who would make no more war. Honor plus safety. ... Poincaré's memoirs suggest that Pétain expected French defeat in February and March 1918. Paul Valéry...in 1934, recalled...his reputation for pessimism. By 1940 these qualities had hardened into "morose skepticism." ... The 1917 alarms left their mark on Pétain's lifelong concern for patriotic morale. When Pétain claimed in the 1930's that education had become his main interest, he meant morale, not knowledge. In 1940 he was convinced...that unpatriotic schoolteachers had been responsible for French defeat.

- Robert Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 (1972), pp. 35-37

- I had the impression of a marble statue; a Roman senator in a museum. Big, vigorous, an impressive figure, face impassive, of a pallor of a really marble hue... Pétain did not appear to me only as a soldier; his greatness does not only derive from his skill at directing a battle, but emanates from his entire personality. No one evokes better than he what the Romans called "great men."

- Jean de Pierrefeu, GQG—secteur I, Volume II (1920), p. 9, quoted in Correlli Barnett, The Swordbearers: Supreme Command in the First World War (1963), pp. 197-198

- I saw General Pétain first in his working room. A fair Pas-de-Calais man of medium height, with a firm and reserved aspect and a masterful regard; a soldier before all, and one with strong will and decided opinions. I was much attracted by him.

- Charles à Court Repington, diary entry (31 March 1916), quoted in Charles à Court Repington, The First World War, 1914–1918: Personal Experiences, Volume I (1920), p. 157

- Went round this morning to the H.Q. of the Armies of the Centre and saw Pétain. I sat in his room while he received all the morning reports, which were read out to him by his Chief of Staff, Colonel Serrigny. I was struck by the quick and businesslike methods of both, and by the acute, pungent, and penetrating remarks of the General.

- Charles à Court Repington, diary entry (28 April 1917), quoted in Charles à Court Repington, The First World War, 1914–1918: Personal Experiences, Volume I (1920), p. 547

- Cold, glacial even, this good-looking blond fellow, already going bald, attracted women and men alike by the intensity of the gaze of his blue eyes.

- Bernard Serrigny, Preface, Trente ans avec Pétain (1959), p. viii

- Pétain's achievement [in resolving the 1917 mutinies] was in fact a greater, far greater miracle than the Marne. ... Immediately after the second war ended, I simply could not praise for his achievements the man who had so often, under the pretext of helping France, placed weapons in Hitler's hands to use against my country. But the years passed, and it seemed to me to be not only a great injustice to Marshal Pétain but a cruel distortion of history to allow the dust of years to settle on what is, I am convinced, a heroic achievement which in the First World War brought victory out of defeat.

- Edward Spears, Two Men who saved France: Pétain and De Gaulle (1966), pp. 62, 65

References

[edit]- ↑ Shortall, Sarah (2021). Soldiers of God in a Secular World: Catholic Theology and Twentieth-Century. Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780674269613.