The Promise (2016 film)

Appearance

The Promise is a 2016 film, set in the final years of the Ottoman Empire, about a love triangle between an Armenian medical student, an American journalist, and a beautiful Armenian woman.

- Directed by Terry George. Written by Terry George and Robin Swicord.

Empires fall. Love survives. (taglines)

| This film article is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

Ana Khesarian

[edit]Mikael Boghosian

[edit]

- How wonderful it must be to go back to the comfort of your American home and write about it.

- [narrating] There was nothing that could be said. Both of us had lost the woman we loved. The French took us to a refugee camp in Egypt. Chris arranged for US visas for me, Yeva, and the orphans. We lost Chris in 1938. He died while reporting on the Spanish Civil War. I adopted yeva, finished my medical studies and set up a practice in Watertown, Massachusetts. After the Japanese attacked Pearl harbor, Yeva joined the women's army corps and fell in love with a young marine lieutenant. And on her wedding day, the orphans joined us in celebration.

- My darling Yeva told me that her greatest wish was that her parents and our dear Ana were here. I told her I know that they *are*. For sure, they are here. And all of your parents and all those families lost in an attempt to wipe our nation from the face of the earth. But we're still here. We're still here.

Taglines

[edit]- Empires fall. Love survives.

About

[edit]

For this reason, most of the great films depicting the Holocaust have been based on true stories: “Europa Europa,” “Schindler's List,” “The Hiding Place,” “The Diary of Anne Frank,” “The Pianist.” There are exceptions (“Son of Saul”), but the slant toward truth-based stories has been real and necessary. To take the most unimaginable human suffering and combine it with the standard conventions of movie fiction somehow feels discordant, at best, and at worst grotesque.

- Q: One of the most chilling lines in the movie is when Oscar’s character says, “It must be so nice to go home and write about this.” Americans are fairly removed from many of the tragedies in our world today, how can we change that?

- Christian Bale: Well, that line is countered by my character’s line because it’s absolutely valid and truthful, but equally truthful is when Chris Myers says, “Yes, but without the press, nobody would know what’s happening.” So, to your question, it shows how important it is to have a free press so we truly know what’s happening, especially now when we’re trying to filter through what’s real and what’s not.

- Christian Bale in "An Interview with the Cast and Creators of The Promise", by Ryan Duncan, Crosswalk.com, (Apr 21, 2017).

- Comparisons between Terry George’s new film The Promise and his 2004 award-winner Hotel Rwanda are evident from the outset. This director, who is fond of telling intimate stories set against the sweep of history, reprises the formula here, again finding the human drama amid a modern genocidal atrocity. If the formula doesn’t work as well this time out, it may just be a matter of the pattern getting too creaky and predictable. Yet the film and its harrowing depiction of the too-little-examined genocide of the Armenian Turks – an extermination at the beginning of World War I that the country of Turkey will not admit to this day – is a respectable offering. Even if the idea of giving focus to a romantic triangle as the narrative lure for a broader depiction of ethnic cleansing is a disheartening comment on the nature of our film consumption, The Promise far outdistances the other recent love story set against the Armenian genocide: The Ottoman Lieutenant, a subpar movie in every respect.

- Marjorie Baumgarten, "The Promise", Austin Chronicle, (April 21, 2017).

- Shot in colorful, ultra-crisp widescreen (though the ultra-high definition of Javier Aguirresarobe’s digital lensing actually lends an unwanted artifice) and scored to the gills by Gabriel Yared, the film has reached epic scale by this point, and yet, our interest has been taxed in too many conflicting ways: Do we want Michael and Ana to get together? If so, are we secretly rooting for something awful to happen to Chris and Maral? When the French Navy shows up (led by none other than Jean Reno), “The Promise” permits itself to plunge these invented characters into the midst of an actual historical standoff at Musa Dagh — one of the few successful Armenian attempts to resist their Turkish oppressors, which means the Ottoman mayor (Rade Serbedzija) may get his wish: Until this point, they have all been witnesses to the genocide, but now, there could be survivors, and the question of who lives and who dies no longer depends on the Turks’ cruelty, but rather on the screenwriters’ caprices.

The final stretch is little more than blatant manipulation, as “The Promise” ill-advisedly attempts to trump its representation of a genocide-scaled real-world tragedy with the scripted fates of its central characters. Astonishingly, the Americans come off as heroes in the end, as when a U.S. embassy official (played by James Cromwell) comes right out and tells a Turkish authority, “You are using this relocation as a cover for the systematic extermination of the Armenian people.” And yet it should be noted that, as broken promises go, President Obama has never followed through on his 2008 campaign pledge: “… As President, I will recognize the Armenian Genocide.”- Peter Debruge, "Film Review: ‘The Promise’", Variety, (Sep 13, 2016).

- Q: Why did you decide it was important to make this movie, and what approach did you take to your role?

- Oscar Isaac: For me, to my shame, I didn’t know about the Armenian genocide before I got this script.To read about that, to read that 1.5 million Armenians perished at the hands of their own government, was horrifying. To this day it’s so little known, and there’s even active denial to it, so that was a big part of it. Also the cast that they put together, and then to learn that 100% of the proceeds would go to charity, it was an extraordinary thing to be part of. My approach was to read as much as I could, to immerse myself in the history of the time. There’s a small museum a few of us got to go to, and then for me, the biggest help was there were these videos and recordings from survivors who would recount the things they witnessed as children. To hear them recounted was heartbreaking, so I did feel some responsibility to tell their story.

- Christian Bale: For me, continuing off from what Oscar was saying, to try and get into that mindset, and to try even in a very small way to understand the pain they must have gone through, in that people were telling them they were lying. They had witnessed it with their own eyes and experienced all that emotion, but people refused to call it what it was: genocide. There are still people today who refuse to call it that. It’s this great unknown genocide, and the lack of consequence may have provoked other genocides that have happened since.

- Oscar Isaac and Christian Bale in "An Interview with the Cast and Creators of The Promise", by Ryan Duncan, Crosswalk.com, (Apr 21, 2017).

- It’s easy to blow raspberries at the epic The Promise, in which Oscar Isaac and Christian Bale compete for the same woman against a backdrop of the Armenian genocide. But only a handful of narrative films have even touched on the Turkish-led massacre of a million and a half Armenians in the early 20th century (which Turkey still officially denies), so The Promise deserves at least a fair synopsis.

- It’s worth asking why so many movies with disasters — natural or man-made — have love triangles at the center. My guess is that filmmakers feel they need to ground so inconceivable a horror in something that audiences can relate to. At least director Terry George and his co-writer, Robin Swicord, are several cuts above the Roland Emmerich template, where hundreds of millions perish while Jake Gyllenhaal tries to summon the words to tell Emmy Rossum that he, you know, likes her. For one thing, Mikael, Ana, and Chris keep their focus on saving orphans, their longings and jealousies expressed in stray love-gazes and bitchy asides. For the viewer, though, attention is divided between praying that the Armenian people will not be exterminated and wondering which man — both admirable — Ana will choose. I guessed (and wrote in my notebook) exactly how the love story would be resolved a half-hour before the climax, a feat that fills me with both pride and disappointment. The chief flaw of The Promise is that there isn’t a single development that you can’t see limping toward you from a great distance.

- David Edelstein, "The Promise Finds a Simpleminded Melodrama Inside the Armenian Genocide", Vulture, (April 21, 2017).

- Well, there's a library of revisionist and denialist material out there about the Armenian Genocide — you know, that it should be thought of not as a genocide but as a civil war. The other side is that this was designed, that it was planned. And as someone who studied these events, it's important to understand the political motivations of both sides so that we can have a discussion, but it's absolutely not a question of did it happen—because it did—but why did it happen. That's the question you need to get to.

- Q': Did the Turkish government give you any problems?

- Terry George: I had a very healthy exchange with a Turkish journalist in LA. The Turkish perspective is that the genocide didn’t happen, it was a war, bad things happened, and lots of people died on both sides. I pointed out to him that was exactly true, but in the case of the Armenians it was their own government who was killing them. So we talked that out. We also had this thing where IMDB was hijacked, the sudden appearance of The Ottoman Lieutenant movie four weeks ago, which was like the reverse image of this film right down to the story. There’s a particular nervousness in Europe I think, both about the film and the political situation.

- Terry George in "An Interview with the Cast and Creators of The Promise", by Ryan Duncan, Crosswalk.com, (Apr 21, 2017).

- With “The Promise,” George, co-writing with Robin Swicord, treats the Armenian genocide of the early part of the 20th century, an action undertaken by the soon-to-be-displaced Ottoman Empire, as a side exercise in its alliance with Germany as World War I was about to break out. Well over a million souls were killed in this action, which the contemporary Turkish government still declines to acknowledge. Indeed, the recent movie “The Ottoman Lieutenant,” set in the same period as this one, is produced in part by Turkish interests and has several scenes in which there’s a pronounced “whatever Armenians WERE killed kind of had it coming” vibe. And this film has been preemptively down-voted on IMDb by Armenian genocide deniers. One nice thing about George is that when he takes on a subject, he doesn’t flinch or back down about the truths he needs to convey. But it’s hard to deny that in some respects, “The Promise” takes a long way to getting around to the meat of the story.

- The movie hits its cinematic stride, as it happens, when events are at their worst. "The Promise" is drenched in production value and replete with ravishing shots of sunrises and sunsets, but it’s in the scenes of fleeing, of battle, and of horrendous loss that the film is at its most effective. The depiction of the savagery inflicted on Armenia is bracing. George is determined to make his story as much about the dead as about the fictional survivors. It’s in that respect that “The Promise” earns its unsettling honor.

- Glenn Kenny “The Promise”, Rogerebert.com, (April 21, 2017).

- Horrible human tragedies — unthinkable calamities involving millions of people — dwarf everything else. If you have a movie about the Holocaust, or Stalin’s starvation of the kulaks, or, as in the case of “The Promise,” the Armenian genocide, the historical event takes precedence. It’s hard to care about fictional characters while remembering the real-life horrors experienced by actual people.

For this reason, most of the great films depicting the Holocaust have been based on true stories: “Europa Europa,” “Schindler's List,” “The Hiding Place,” “The Diary of Anne Frank,” “The Pianist.” There are exceptions (“Son of Saul”), but the slant toward truth-based stories has been real and necessary. To take the most unimaginable human suffering and combine it with the standard conventions of movie fiction somehow feels discordant, at best, and at worst grotesque.]]

“The Promise” is hardly grotesque. It has good things in it, but by the end, it just feels like a failed manipulation. The reality that it’s trying to present and make us feel — the Ottoman government’s murder of 1.5 million Armenians in the 1910s — remains what it was before, a ghastly fact. The movie doesn’t activate that event through drama, even as our awareness of history keeps us at some distance from the struggles of the fictional characters. - Basically, there was a calculation here that didn’t pan out. The idea was that history would add importance to the fictional story, and the fictional story would add drama to the history. Instead, the opposite happened: The historical context renders the fictional story trivial, while the fictional story keeps the audience removed from the history. We end up with an unimportant movie about important events.

- Mick LaSalle "‘The Promise’ is too fictional a take on Armenian genocide", SF Gate, (Thursday, April 20, 2017).

- Parents need to know that The Promise is an earnest but disturbing wartime drama about the Armenian genocide in Turkey during World War I. Scenes depict graphic atrocities, hangings, beatings, street riots, burning buildings, mass graves full of women and children, execution-style killings, and other brutal, intense images. There's also some drinking (sometimes to excess) and kissing, as well as implied sex (no graphic nudity); language is very infrequent, but there is one use each of "s--t" and "hell." While it's not easy to watch, the movie does show how war can prompt some people to rise to the occasion, demonstrate courage, and work to save innocents.

- S. Jhoanna Robledo, "The Promise", Common Sense Media, (Apr. 21, 2017).

- The events of “The Promise” transpire some 30 years prior to the storyline of “Casablanca,” but we can’t help but be reminded of the latter film when we witness this love triangle set against the backdrop of the horrors of a world war.

- The coincidences in “The Promise” are too frequent. (Chris and Ana and Michael, or some combination thereof, always seem to be able to find each other, even in the midst of utter chaos.) The melodrama is a little too heavy-handed at times. And for a movie that clocks in at 134 minutes, all of a sudden it feels as if we’re rushing through the conclusion and to a touching epilogue that might have been even more effective had it been given a little more real estate.

Yes, “The Promise” veers into corny territory, and yes, it’s derivative of better war romances — but it’s a solid and sobering reminder of the atrocities of war, bolstered by strong performances from Isaac and Bale, two of the best actors of their generation.- Richard Roeper, "‘The Promise’: Bale, Isaac strong in sometimes corny romance", (4/20/2017).

- Credit the producers, including the self-made Armenian-American billionaire Kirk Kerkorian, who died in 2015 at 98, for treating the film as a passion project. That passion is still evident here – how could it not be? – as audiences watch in horror at the systematic extermination of 1.5 million Armenians. Turkey, the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, still refuses to recognize these mass killings as genocide – as does the U.S. The Promise has no such qualms, however, allowing us to bear witness to atrocities that foreshadow the rise of Hitler and the existential horror of the Holocaust.

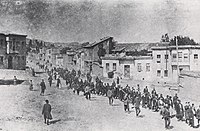

What a shame, then, that the script by Robin Swicord (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) feels the need to distract us with a bland, invented romance that doesn’t amount to hill of beans in this tormented world. Oscar Isaac (Inside Llewyn Davis, Star Wars: The Force Awakens) takes the Dr. Zhivago-like role of Michael Boghosian, an Armenian medical student who makes a promise to marry a young woman (Angela Sarafyan) to help finance his studies in Constantinople. One of the temptations of the big city is Ana (Charlotte Le Bon), a dance instructor heavily involved with Chris Myers (Christian Bale), an American reporter covering the hostilities for the Associated Press. Meanwhile, Armenians are evicted from their homes and death-marched through the desert as World War I looms.- Peter Travers, "‘The Promise’ Review: Who Wants an Old-School Love-Triangle Epic About Genocide?", Rolling Stone, (Apr, 19, 2017).

- Throughout its two-hour plus running time, there is nary an explanation of the political machinations behind the persecution of the Armenians. There's a bit of chit-chat and singing with some German soldiers, a mean Turkish father, and then suddenly everyone's being executed and shipped off to labor camps while villages burn.

The lack of exposition could be intended to align us with Mikael's naive perspective. But you'll definitely leave "The Promise" with far more questions than you started. Perhaps we can never really answer why one group commits genocide against another, but it feels slightly irresponsible to make a film ostensibly shedding light on this atrocity and then not attempt to explain it in the least.

Instead, "The Promise" is mostly concerned with the love triangle between Ana, Mikael and Chris, the reporter. And even the love triangle itself is a disappointment, as these men never seem too concerned that the other is romancing his girl.

The usually charismatic Isaac is saddled with a dud of a character. Mikael spends most of the film buffeted by forces beyond his control and deferring to the desires of others, such as the army and his mother (Shohreh Aghdashloo). It's not until the third act that he starts to make his own decisions. The swaggering heroics are left to Bale as the Hemingway-esque American foreign correspondent.- Kate Walsh, "The Promise,' an epic melodrama set during the Armenian genocide, falls frustratingly flat", Los Angeles Times, (Apr 20, 2017).

- Q: What was it about The Promise that said “I have to do this”?

- BALE: I’m always on the verge of quitting. I hate what I do, but I love it as well. And occasionally, there’ll be something which I surprise myself with my choice. It keeps you going. It can result in big mistakes but sometimes can result in, you know, sort of happy accidents. This project came primarily because of my lack of education is why I did this project. I had no idea about the Armenian genocide, I’d never heard of it in my life.

- Q: I was going to say that the type of film that this is, is incredibly hard to make nowadays. I’m very impressed you guys were able to pull this off.

- BALE: Well, it only happened because it was a single financier, Kirk Kerkorian, and that’s it. People have been trying to make not this kind of movie, but specifically a movie about the Armenian genocide, and there have been some made, but not on this skill. And people have been trying to make this film for some time, I mean, Kirk Kerkorian himself, three times when he was running MGM was unable to make this film despite his best efforts, because each time it was thwarted because of interests whose interests were not in having the film made. So, many years in the making, and that was of course intriguing to me as well.

- Q: When you think back on the making of The Promise, is there a day or two that you’ll always remember? Like memorable moments from filming?

- BALE: Yeah, I think actually, there’s a scene by the river, that’s very memorable for me because in educating myself about the genocide, it was incredibly barbaric. And in wishing to make a sweeping epic, Terry did not actually want to show that, and that confused me for quite a long time, I couldn’t understand why he didn’t want to, but it’s the director’s film, any film is the director’s, so you have to try to understand their point of view and go with the way that they wish to make the film. And in trying to understand that, and very much his reasoning was that he wanted this to be used for educational resources and for young people to be able to watch it without it becoming overly shocking to be able to stomach, and the truth is stomach-churning. So therefore an awful lot of the time, there is reference to, or there’s a suggestion to what is happening off screen, but not so many occasions where you actually see the consequences, and so that day stuck with me a great deal. And also because of the involvement of people whose families were directly involved in it, and so that was a very poignant day for them.

- Steve 'Frosty' Weintraub, "Christian Bale on ‘The Promise’, ‘The Prestige’, and Why He’s Always on the Verge of Quitting", Collider, (April 20, 2017).

Cast

[edit]- Oscar Isaac — Mikael

- Charlotte Le Bon — Ana

- Christian Bale — Chris Myers

- Daniel Giménez Cacho — Father Andreasian

- Shohreh Aghdashloo — Marta

- Rade Šerbedžija — Stephan

External links

[edit]- The Promise quotes at the Internet Movie Database