Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (January 4, 1643 – March 31, 1727 or in Old Style: December 25, 1642 – March 20, 1727) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the greatest mathematicians and physicists and among the most influential scientists of all time. He was a key figure in the philosophical revolution known as the Enlightenment. His book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

Quotes

[edit]

- Amicus Plato — amicus Aristoteles — magis amica veritas

- Plato is my friend — Aristotle is my friend — but my greatest friend is truth.

- These are notes in Latin that Newton wrote to himself that he titled: Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae [Certain Philosophical Questions] (c. 1664)

- Variant translations: Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my best friend is truth.

Plato is my friend — Aristotle is my friend — truth is a greater friend. - This is a variation on a much older adage, which Roger Bacon attributed to Aristotle: Amicus Plato sed magis amica veritas. Bacon was perhaps paraphrasing a statement in the Nicomachean Ethics: Where both are friends, it is right to prefer truth.

- The best and safest method of philosophizing seems to be, first to enquire diligently into the properties of things, and to establish these properties by experiment, and then to proceed more slowly to hypothesis for the explanation of them. For hypotheses should be employed only in explaining the properties of things, but not assumed in determining them, unless so far as they may furnish experiments.

- Letter to Ignatius Pardies (1672) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (Feb. 1671/2) as quoted by William L. Harper, Isaac Newton's Scientific Method: Turning Data Into Evidence about Gravity and Cosmology (2011)

- If I have seen further it is by standing on ye sholders of Giants.

- Letter to Robert Hooke (15 February 1676) [dated as 5 February 1675 using the Julian calendar with March 25th rather than January 1st as New Years Day, equivalent to 15 February 1676 by Gregorian reckonings.] A facsimile of the original is online at The digital Library. The quotation is 7-8 lines up from the bottom of the first page. The phrase is most famous as an expression of Newton's but he was using a metaphor which in its earliest known form was attributed to Bernard of Chartres by John of Salisbury: Bernard of Chartres used to say that we [the Moderns] are like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants [the Ancients], and thus we are able to see more and farther than the latter. And this is not at all because of the acuteness of our sight or the stature of our body, but because we are carried aloft and elevated by the magnitude of the giants.

- Modernized variants: If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

If I have seen further it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants.

- I have not been able to discover the cause of those properties of gravity from phenomena, and I frame no hypotheses; for whatever is not deduced from the phenomena is to be called a hypothesis, and hypotheses, whether metaphysical or physical, whether of occult qualities or mechanical, have no place in experimental philosophy.

- Letter to Robert Hooke (15 February 1676) [5 February 1676 (O.S.)]

- Bullialdus wrote that all force respecting the Sun as its center & depending on matter must be reciprocally in a duplicate ratio of the distance from the center.

- Letter to Edmund Halley (June 20, 1686) quoted in I. Bernard Cohen and George E. Smith, ed.s, The Cambridge Companion to Newton (2002) p. 204

- 1. Fidelity & Allegiance sworn to the King is only such a fidelity and obedience as is due to him by the law of the land; for were that faith and allegiance more than what the law requires, we would swear ourselves slaves, and the King absolute; whereas, by the law, we are free men, notwithstanding those Oaths. 2. When, therefore, the obligation by the law to fidelity and allegiance ceases, that by the Oath also ceases...

- Letter to Dr. Covel Feb. 21, (1688-9) Thirteen Letters from Sir Isaac Newton to J. Covel, D.D. (1848)

- It seems to me, that if the matter of our sun and planets and all the matter of the universe, were evenly scattered throughout all the heavens, and every particle had an innate gravity towards all the rest, and the whole of space throughout which this matter was scattered was but finite, the matter on [toward] the outside of this space would, by its gravity, tend towards all the matter on the inside, and, by consequence, fall down into the middle of the whole space, and there compose one great spherical mass. But if the matter was evenly disposed throughout an infinite space it could never convene into one mass; but some of it would convene into one mass and some into another, so as to make an infinite number of great masses, scattered at great distances from one another throughout all that infinite space.

- Four Letters to Bentley (1692) first letter

- When I wrote my treatise about our System, I had an eye upon such principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity and nothing can rejoice me more than to find it useful for that purpose. But if I have done the public any service this way, 'tis due to nothing but industry and a patient thought.

- Newton to Bentley, 10 December 1692 (first letter), The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, ed. H. W. Turnbull (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 3:233. Referenced on p. 383 of Snobelen SD: "The Theology of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica: A Preliminary Survey," pp. 377–412, Neue Zeitschrift für Systematische Theologie und Religionsphilosophie, Volume 52, Issue 4 (Jan 2010)

- It is inconceivable that inanimate brute matter should, without the mediation of something else which is not material, operate upon and affect other matter without mutual contact, as it must be, if gravitation in the sense of Epicurus, be essential and inherent in it. And this is one reason why I desired you would not ascribe innate gravity to me. That gravity should be innate, inherent, and essential to matter, so that one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum, without the mediation of anything else, by and through which their action and force may be conveyed from one to another, is to me so great an absurdity that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking can ever fall into it. Gravity must be caused by an agent acting constantly according to certain laws; but whether this agent be material or immaterial, I have left open to the consideration of my readers.

- Newton to Bentley, 25 February 1692/3, The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, ed. H. W. Turnbull (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 3:253-254. Quoted in: Janiak, Andrew, "Newton’s Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/newton-philosophy/

- The 2300 years do not end before the year 2132 nor after 2370.

The time times & half time do not end before 2060. .... It may end later, but I see no reason for its ending sooner. This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fancifull men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, & by doing so bring the sacred prophesies into discredit as often as their predictions fail. Christ comes as a thief in the night, & it is not for us to know the times & seasons which God hath put into his own breast.- An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture (1704), regarding his calculations "Of the End of the World" based upon the prophecies of Daniel, quoted in Look at the Moon! the Revelation Chronology (2007) by John A. Abrams, p. 141

- Modern typographical and spelling variant:

- This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophesies into discredit as often as their predictions fail.

- To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. 'Tis much better to do a little with certainty, & leave the rest for others that come after you, than to explain all things by conjecture without making sure of any thing.

- Statement from unpublished notes for the Preface to Opticks (1704) quoted in Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (1983) by Richard S. Westfall, p. 643

- I keep the subject constantly before me, and wait 'till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light.

- Reply upon being asked how he made his discoveries, as quoted in "Biographia Britannica: Or the Lives of the Most Eminent Persons who Have Flourished in Great Britain from the Earliest Ages Down to the Present Times, Volume 5 ", by W. Innys, (1760), p. 3241. Fuller quote:

- "The mark that seems most of all to distinguish it [the character of his genius] is this, that he himself was the truest judge, and made the justest estimation of it. One day, when one of this friends had said some handsome things of his extraordinary talents, Sir Isaac, in an easy and unaffected way, assured him, that for his own part he was sensible, that whatever he had done worth notice, was owing to a patience of thought, rather than an extraordinary sagacity which he was endowed with above other men. [He begins his first letter to Dr Bentley in 1692, thus, 'When I wrote my treatise about our system, I had an eye upon such principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity, and nothing can rejoice me more than to find it useful for that purpose. But if I have done the public any service this way, it is due to nothing but industry and patient thought.' Four letters, &c. Edit. 1756, 2vo.] I keep the subject constantly before me, and wait ’till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light. And hence we are able to give a very natural account of that unusual kind of horror which he had for all disputes upon these points; a steady unbroken attention was his peculiar felicity, he knew it, and he knew the value of it. In such a situation of mind, controversy must needs be looked upon him as his bane. However, he was at a great distance from being steeped in Philosophy: on the contrary, he could lay aside his thoughts, though engaged in the most intricate researches, when his other affairs required his attendance and, as soon as he had leisure, resume the subject at the point where he left off. This he seems to have done, not so much by any extraordinary strength of memory, as by the force of his inventive faculty, to which every thing opened itself again with ease, if nothing intervened to ruffle him. The readiness of his invention made him not think of putting his memory much to the trial; but this was the offspring of a vigorous intenseness of thought, out of which he was but a common man."

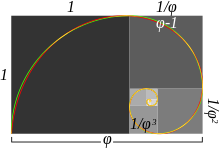

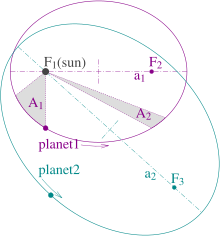

- In the beginning of the year 1665 I found the method of approximating Series and the Rule for reducing any dignity of any Binomial into such a series. The same year in May I found the method of tangents of Gregory and Slusius, and in November had the direct method of Fluxions, and the next year in January had the Theory of Colours, and in May following I had entrance into the inverse method of Fluxions. And the same year I began to think of gravity extending to the orb of the Moon, and having found out how to estimate the force with which [a] globe revolving within a sphere presses the surface of the sphere, from Kepler's Rule of the periodical times of the Planets being in a sesquialterate proportion of their distances from the centers of their orbs I deduced that the forces which keep the Planets in their Orbs must [be] reciprocally as the squares of their distances from the centers about which they revolve: and thereby compared the force requisite to keep the Moon in her orb with the force of gravity at the surface of the earth, and found them answer pretty nearly. All this was in the two plague years of 1665 and 1666, for in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention, and minded Mathematicks and Philosophy more than at any time since. What Mr Hugens has published since about centrifugal forces I suppose he had before me. At length in the winter between the years 1676 and 1677 I found the Proposition that by a centrifugal force reciprocally as the square of the distance a Planet must revolve in an Ellipsis about the center of the force placed in the lower umbilicus of the Ellipsis and with a radius drawn to that center describe areas proportional to the times. And in the winter between the years 1683 and 1684 this Proposition with the Demonstration was entered in the Register book of the R. Society. And this is the first instance upon record of any Proposition in the higher Geometry found out by the method in dispute. In the year 1689 Mr Leibnitz, endeavouring to rival me, published a Demonstration of the same Proposition upon another supposition, but his Demonstration proved erroneous for want of skill in the method.

- (ca. 1716) A Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection of Books and Papers Written by Or Belonging to Sir Isaac Newton (1888) Preface

- Also partially quoted in Sir Sidney Lee (ed.), The Dictionary of National Biography Vol.40 (1894)

- I have studied these things — you have not.

- Reported as Newton's response, whenever Edmond Halley would say anything disrespectful of religion, by Sir David Brewster in The Life of Sir Isaac Newton (1831). This has often been quoted in recent years as having been a statement specifically defending Astrology. Newton wrote extensively on the importance of Prophecy, and studied Alchemy, but there is little evidence that he took favourable notice of astrology[1]. In a footnote, Brewster attributes the anecdote to the astronomer Nevil Maskelyne who is said to have passed it on to Oxford professor Stephen Peter Rigaud[2]

- I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

- Memoirs of the Life, Writings, and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton (1855) by Sir David Brewster (Volume II. Ch. 27). Compare: "As children gath'ring pebbles on the shore", John Milton, Paradise Regained, Book iv. Line 330

- In default of any other proof, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God.

- Attributed to Newton as "A défaut d'autres preuves, le pouce me convaincrait de l'existence de Dieu" in a treatise on palmistry: d'Arpentigny, Stanislas (1856). "IV: Le pouce" (in French). La science de la main (2nd ed.). Paris, France: Coulon-Pineau. p. 53. A later translation by Edward Heron-Allen renders the phrase as "In default of any other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of God", and acknowledges that it does not seem to appear in any of Newton's works [d'Arpentigny, Casimir Stanislas (1889). "Sub-Section IV: The Thumb" (in English). The Science of the Hand. London, England: Ward, Lock and Co.. p. 138.]

- Reported as something said by Newton in a section on palmistry in Charles Dickens's All the Year Round (1864), Vol. 10, p. 346; later found in "The Book of the Hand" (1867) by A R. Craig, S. Low and Marston, p. 51:

- "In want of other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God; as without the thumb the hand would be a defective and incomplete instrument, so without the moral will, logic, decision, faculties of which the thumb in different degrees offers the different signs, the most fertile and the most brilliant mind would only be a gift without worth. [No closing quotations marks exist to specify the end of the quotation and the beginning of the author's commentary.]

- A slight variant of this is cited as something Newton once "exclaimed" in Human Nature : An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective, Vol. 1, Issues 7-12 (1978), p. 47: "In the absence of any other proof, the thumb alone would convince me of God's existence."

- "In want of other proofs, the thumb would convince me of the existence of a God; as without the thumb the hand would be a defective and incomplete instrument, so without the moral will, logic, decision, faculties of which the thumb in different degrees offers the different signs, the most fertile and the most brilliant mind would only be a gift without worth. [No closing quotations marks exist to specify the end of the quotation and the beginning of the author's commentary.]

- We account the Scriptures of God to be the most sublime philosophy. I find more sure remarks of authenticity in the Bible than in any profane history whatever.

- Anecdote reported by Dr. Robert Smith, late Master of Trinity College, to his student Richard Watson, as something that Newton expressed when he was writing his Commentary On Daniel. In Watson's Apology for the Bible. London 8vo. (1806), p. 57

- Oh, Diamond! Diamond! thou little knowest what mischief thou hast done!

- This is from an anecdote found in St. Nicholas magazine, Vol. 5, No. 4, (February 1878) :

- Sir Isaac Newton had on his table a pile of papers upon which were written calculations that had taken him twenty years to make. One evening, he left the room for a few minutes, and when he came back he found that his little dog "Diamond" had overturned a candle and set fire to the precious papers, of which nothing was left but a heap of ashes.

- It is the perfection of God's works that they are all done with the greatest simplicity. He is the God of order and not of confusion. And therefore as they would understand the frame of the world must endeavor to reduce their knowledge to all possible simplicity, so must it be in seeking to understand these visions.

- Cited in Rules for methodizing the Apocalypse, Rule 9, from a manuscript published in The Religion of Isaac Newton (1974) by Frank E. Manuel, p. 120, quoted in Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (1983) by Richard S. Westfall, p. 326, in Fables of Mind: An Inquiry Into Poe's Fiction (1987) by Joan Dayan, p. 240, and in Everything Connects: In Conference with Richard H. Popkin (1999) by Richard H. Popkin, James E. Force, and David S. Katz, p. 124

- Truth is ever to be found in simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.

- Cited in Rules for methodizing the Apocalypse, Rule 9, from a manuscript published in The Religion of Isaac Newton (1974) by Frank E. Manuel, p. 120, as quoted in Socinianism And Arminianism : Antitrinitarians, Calvinists, And Cultural Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Europe (2005) by Martin Mulsow, Jan Rohls, p. 273.

- Variant: Truth is ever to be found in the simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.

- As quoted in God in the Equation : How Einstein Transformed Religion (2002) by Corey S. Powell, p. 29

- God created everything by number, weight and measure.

- As quoted in Symmetry in Plants (1998) by Roger V. Jean and Denis Barabé, p. xxxvii, a translation of a Latin phrase he wrote in a student's notebook, elsewhere given as Numero pondere et mensura Deus omnia condidit. This is similar to Latin statements by Thomas Aquinas, and even more ancient statements of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras. See also Wisdom of Solomon 11:20

- We must believe in one God that we may love & fear him. We must believe that he is the father Almighty, or first author of all things by the almighty power of his will, that we may thank & worship him & him alone for our being and for all the blessings of this life < insertion from f 43v > We must believe that this is the God of moses & the Jews who created heaven & earth & the sea & all things therein as is expressed in the ten commandments, that we may not take his name in vain nor worship images or visible resemblances nor have (in our worship) any other God then him. For he is without similitude he is the invisible God whom no eye hath seen nor can see, & therefore is not to be worshipped in any visible shape. He is the only invisible God & the only God whom we are to worship & therefore we are not to worship any visible image picture likeness or form. We are not forbidden to give the name of Gods to Angels & Kings but we are forbidden to worship them as Gods. For tho there be that are called Gods whether in heaven or in earth (as there are Gods many & Lords many) yet to us there is but one God the Father of whom are all things & we in him & our Lord Jesus Christ by whom are all things & we in him, that is, but one God & one Lord in our worship: One God & one mediator between God & man the man Christ Jesus. We are forbidden to worship two Gods but we are not forbidden to worship one God, & one Lord: one God for creating all things & one Lord for redeeming us with his blood. We must not pray to two Gods, but we may pray to one God in the name of one Lord. We must believe therefore in one Lord Jesus Christ that we may behave our selves obediently towards him as subjects & keep his laws, & give him that honour & glory & worship which is due to him as our Lord & King or else we are not his people. We must believe that this Lord Jesus is the Christ, or Messiah the Prince predicted by Daniel, & we must worship him as the Messiah or else we are no Christians. The Jews who were taught to have but one God were also taught to expect a king, & the Christians are taught in their Creed to have the same God & to believe that Jesus is that King.

- Drafts on the history of the Church (Section 3). Yahuda Ms. 15.3, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel. 2006 Online Version at Newton Project

- Whence are you certain that ye Ancient of Days is Christ? Does Christ anywhere sit upon ye Throne?

- He wrote in discussing with John Locke the passage of Daniel 7:9. The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Vol. III, Letter 362. Cited in The Watchtower magazine, 1977, 4/15, article: Isaac Newton’s Search for God.

- Who is a liar, saith John, but he that denyeth that Jesus is the Christ? He is Antichrist that denyeth the Father & the Son. And we are authorized also to call him God: for the name of God is in him. Exod. 23.21. And we must believe also that by his incarnation of the Virgin he came in the flesh not in appearance only but really & truly , being in all things made like unto his brethren (Heb. 2 17) for which reason he is called also the son of man.

- Drafts on the history of the Church (Section 3). Yahuda Ms. 15.3, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel. 2006 Online Version at Newton Project

- I have that honour for him as to believe that he wrote good sense; and therefore take that sense to be his which is the best.

- Speaking of the apostle John's writings. Cited in The Watchtower magazine, 1977, 4/15.

- As all regions below are replenished with living creatures... so may the heavens above be replenished with beings whose nature we do not understand. He that shall well consider the strange and wonderful nature of life and the frame of the Animals, will think nothing beyond the possibility of nature, nothing too hard for the omnipotent power of God. And as the Planets remain in their orbs, so may any other bodies subsist at any distance from the earth, and much more may beings, who have sufficient power of self motion, move whether they will, and continue in any regions of the heavens whatever, there to enjoy the society of one another, and by their messengers or Angels to rule the earth and convers with the remotest regions. Thus may the whole heavens or any part thereof whatever be the habitation of the Blessed, and at the same time the earth be subject to their dominion. And to have thus the liberty and dominion of the whole heavens and the choice of the happiest places for abode seems a greater happiness than to be confined to any one place whatever.

- As quoted by Frank Edward Manuel, The Religion of Isaac Newton (1977)

- The ancients considered mechanics in a twofold respect; as rational, which proceeds accurately by demonstration, and practical. To practical mechanics all the manual arts belong, from which mechanics took its name. But as artificers do not work with perfect accuracy, it comes to pass that mechanics is so distinguished from geometry, that what is perfectly accurate is called geometrical; what is less so is called mechanical. But the errors are not in the art, but in the artificers. He that works with less accuracy is an imperfect mechanic: and if any could work with perfect accuracy, he would be the most perfect mechanic of all; for the description of right lines and circles, upon which geometry is founded, belongs to mechanics. Geometry does not teach us to draw these lines, but requires them to be drawn; for it requires that the learner should first be taught to describe these accurately, before he enters upon geometry; then it shows how by these operations problems may be solved.

- Preface (8 May 1686)

- Our design, not respecting arts, but philosophy, and our subject, not manual, but natural powers, we consider chiefly those things which relate to gravity, levity, elastic force, the resistance of fluids, and the like forces, whether attractive or impulsive; and therefore we offer this work as mathematical principles of philosophy; for all the difficulty of philosophy seems to consist in this — from the phenomena of motions to investigate the forces of nature, and then from these forces to demonstrate the other phenomena...

- Preface

- I wish we could derive the rest of the phenomena of nature by the same kind of reasoning from mechanical principles; for I am induced by many reasons to suspect that they may all depend upon certain forces by which the particles of bodies, by some causes hitherto unknown, are either mutually impelled towards each other, and cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from each other; which forces being unknown, philosophers have hitherto attempted the search of nature in vain; but I hope the principles here laid down will afford some light either to that or some truer method of philosophy.

- Preface

- Rational mechanics must be the science of the motions which result from any forces, and of the forces which are required for any motions, accurately propounded and demonstrated. For many things induce me to suspect, that all natural phenomena may depend upon some forces by which the particles of bodies are either drawn towards each other, and cohere, or repel and recede from each other: and these forces being hitherto unknown, philosophers have pursued their researches in vain. And I hope that the principles expounded in this work will afford some light, either to this mode of philosophizing, or to some mode which is more true.

- Preface, translation in William Whewell's History of the Inductive Sciences (1837)

- I do not define time, space, place, and motion, as being well known to all. Only I must observe, that the common people conceive those quantities under no other notions but from the relation they bear to sensible objects. And thence arise certain prejudices, for the removing of which it will be convenient to distinguish them into absolute and relative, true and apparent, mathematical and common.

- It is indeed a matter of great difficulty to discover, and effectually to distinguish, the true motions of particular bodies from the apparent; because the parts of that immovable space, in which those motions are performed, do by no means come under the observation of our senses. Yet the thing is not altogether desperate; for we have some arguments to guide us, partly from the apparent motions, which are the differences of the true motions; partly from the forces, which are the causes and effects of the true motions.

- Definitions - Scholium

- We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.

- "Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy" : Rule I

- Every body continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it.

- Laws of Motion, I

- The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impressed; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impressed.

- Laws of Motion, II

- To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction; or, the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

- Laws of Motion, III

- Hypotheses non fingo.

- I frame no hypotheses.

- A famous statement in the "General Scholium" of the third edition, indicating his belief that the law of universal gravitation was a fundamental empirical law, and that he proposed no hypotheses on how gravity could propagate.

- Variant translation: I feign no hypotheses.

- As translated by Alexandre Koyré (1956)

- I have not as yet been able to discover the reason for these properties of gravity from phenomena, and I do not feign hypotheses. For whatever is not deduced from the phenomena must be called a hypothesis; and hypotheses, whether metaphysical or physical, or based on occult qualities, or mechanical, have no place in experimental philosophy. In this philosophy particular propositions are inferred from the phenomena, and afterwards rendered general by induction.

- As translated by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman (1999)

- I frame no hypotheses.

Scholium Generale (1713; 1726)

[edit]

- From The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1729) as translated by Andrew Motte (1846)

- But it is not to be conceived that mere mechanical causes could give birth to so many regular motions: since the Comets range over all parts of the heavens, in very eccentric orbits. For by that kind of motion they pass easily through the orbs of the Planets, and with great rapidity; and in their aphelions, where they move the slowest, and are detain'd the longest, they recede to the greatest distances from each other, and thence suffer the least disturbance from their mutual attractions.

- This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being. And if the fixed Stars are the centers of other like systems, these being form'd by the like wise counsel, must be all subject to the dominion of One; especially, since the light of the fixed Stars is of the same nature with the light of the Sun, and from every system light passes into all the other systems. And lest the systems of the fixed Stars should, by their gravity, fall on each other mutually, he hath placed those Systems at immense distances one from another.

- This Being governs all things, not as the soul of the world, but as Lord over all: And on account of his dominion he is wont to be called Lord God παντοκρáτωρ or Universal Ruler. For God is a relative word, and has a respect to servants; and Deity is the dominion of God, not over his own body, as those imagine who fancy God to be the soul of the world, but over servants. The supreme God is a Being eternal, infinite, absolutely perfect; but a being, however perfect, without dominion, cannot be said to be Lord God; for we say, my God, your God, the God of Israel, the God of Gods, and Lord of Lords; but we do not say, my Eternal, your Eternal, the Eternal of Israel, the Eternal of Gods; we do not say, my Infinite, or my Perfect: These are titles which have no respect to servants. The word God usually signifies Lord; but every lord is not a God. It is the dominion of a spiritual being which constitutes a God; a true, supreme or imaginary dominion makes a true, supreme or imaginary God. And from his true dominion it follows, that the true God is a Living, Intelligent and Powerful Being; and from his other perfections, that he is Supreme or most Perfect. He is Eternal and Infinite, Omnipotent and Omniscient; that is, his duration reaches from Eternity to Eternity; his presence from Infinity to Infinity; he governs all things, and knows all things that are or can be done. He is not Eternity or Infinity, but Eternal and Infinite; he is not Duration or Space, but he endures and is present. He endures for ever, and is every where present; and by existing always and every where, he constitutes Duration and Space. Since every particle of Space is always, and every indivisible moment of Duration is every where,certainly the Maker and Lord of all things cannot be never and no where. Every soul that has perception is, though in different times and in different organs of sense and motion, still the same indivisible person. There are given successive parts in duration, co-existent parts in space, but neither the one nor the other in the person of a man, or his thinking principle; and much less can they be found in the thinking substance of God. Every man, so far as he is a thing that has perception, is one and the same man during his whole life, in all and each of his organs of sense. God is the same God, always and every where. He is omnipresent, not virtually only, but also substantially; for virtue cannot subsist without substance. In him are all things contained and moved; yet neither affects the other: God suffers nothing from the motion of bodies; bodies find no resistance from the omnipresence of God. 'Tis allowed by all that the supreme God exists necessarily; and by the same necessity he exists always and every where. Whence also he is all similar, all eye, all ear, all brain, all arm, all power to perceive, to understand, and to act; but in a manner not at all human, in a manner not at all corporeal, in a manner utterly unknown to us. As a blind man has no idea of colours, so have we no idea of the manner by which the all-wise God perceives and understands all things. He is utterly void of all body and bodily figure, and can therefore neither be seen, nor heard, nor touched; nor ought to be worshipped under the representation of any corporeal thing. We have ideas of his attributes, but what the real substance of any thing is, we know not. In bodies we see only their figures and colours, we hear only the sounds, we touch only their outward surfaces, we smell only the smells, and taste the favours; but their inward substances are not to be known, either by our senses, or by any reflex act of our minds; much less then have we any idea of the substance of God. We know him only by his most wise and excellent contrivances of things, and final causes; we admire him for his perfections; but we reverence and adore him on account of his dominion. For we adore him as his servants; and a God without dominion, providence, and final causes, is nothing else but Fate and Nature. Blind metaphysical necessity, which is certainly the same always and every where, could produce no variety of things. All that diversity of natural things which we find, suited to different times and places, could arise from nothing but the ideas and will of a Being necessarily existing. But by way of allegory, God is said to see, to speak, to laugh, to love, to hate, to desire, to give, to receive, to rejoice, to be angry, to fight, to frame, to work, to build. For all our notions of God are taken from the ways of mankind, by a certain similitude which, though not perfect, has some likeness however. And thus much concerning God; to discourse of whom from the appearances of things, does certainly belong to Natural Philosophy.

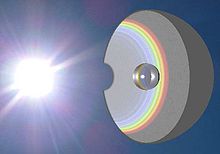

- There were several editions of Opticks in English and in Latin made in Newtons lifetime, including expansions of the original 16 "Queries" to eventually number 31.

- Do not Bodies act upon Light at a distance, and by their action bend its Rays; and is not this action (caeteris paribus) [all else being equal] strongest at the least distance?

- Query 1

- Do not the Rays which differ in Refrangibility differ also in Flexibility; and are they not by their different inflexions separated from one another, so as after separation to make the Colours in the three Fringes... ? And after what manner are they inflected to make those Fringes?

- Query 2

- Are not the Rays of Light in passing by the edges and sides of Bodies, bent several times backwards and forwards, with a motion like that of an Eel? And do not the three Fringes of colour'd Light... arise from three such bendings?

- Query 3

- Do not the Rays of Light which fall upon Bodies, and are reflected or refracted, begin to bend before they arrive at the Bodies; and are they not reflected, refracted, and inflected, by one and the same Principle, acting variously in various Circumstances?

- Query 4

- Do not Bodies and Light act mutually upon one another; that is to say, Bodies upon Light in emitting, reflecting, refracting and inflecting it, and Light upon Bodies for heating them, and putting their parts into a vibrating motion wherein heat consists?

- Query 5

- Do not several sorts of Rays make Vibrations of several bignesses, which according to their bigness excite Sensations of several Colours, much after the manner that the Vibrations of the Air, according to their several bignesses excite Sensations of several Sounds? And particularly do not the most refrangible Rays excite the shortest Vibrations for making a Sensation of deep violet, the least refrangible the largest form making a Sensation of deep red, and several intermediate sorts of Rays, Vibrations of several intermediate bignesses to make Sensations of several intermediate Colours?

- Query 13

- Is not the Heat of the warm Room convey'd through the Vacuum by the Vibrations of a much subtiler Medium than Air, which after the Air was drawn out remained in the Vacuum? And is not this Medium the same with that Medium by which Light is refracted and reflected and by whose Vibrations Light communicates Heat to Bodies, and is put into Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission? ...And do not hot Bodies communicate their Heat to contiguous cold ones, by the Vibrations of this Medium propagated from them into the cold ones? And is not this Medium exceedingly more rare and subtile than the Air, and exceedingly more elastick and active? And doth it not readily pervade all Bodies? And is it not (by its elastick force) expanded through all the Heavens?

- Query 18

- Doth not this Æthereal Medium in passing out of Water, Glass, Crystal, and other compact and dense Bodies into empty Spaces, grow denser and denser by degrees, and by that means refract the Rays of Light not in a point, but by bending them gradually in curve Lines? And doth not the gradual condensation of this Medium extend to some distance from the Bodies, and thereby cause the Inflexions of the Rays of Light, which pass by the edges of dense Bodies, at some distance from the Bodies?

- Query 20

- Is not this Medium [æther] much rarer within the dense Bodies of the Sun, Stars, Planets, and Comets, than in the empty celestial Spaces between them? And in passing from them to great distances, doth it not grow denser and denser perpetually, and thereby cause the gravity of those great Bodies towards one another, and of their parts towards the Bodies; every Body endeavouring to go from the denser parts of the Medium towards the rarer? ...And though this Increase of density may at great distances be exceeding stow, yet if the elastick force of this Medium be exceeding great, it may suffice to impel Bodies from the denser parts of the Medium towards the rarer, with all that power which we call Gravity. And that the elastic force of this Medium is exceeding great, may be gather'd from the swiftness of its Vibrations.

- Query 21

- As Attraction is stronger in small Magnets than in great ones in proportion to their Bulk, and Gravity is greater in the Surfaces of small Planets than in those of great ones in proportion to their bulk, and small Bodies are agitated much more by electric attraction than great ones; so the smallness of the Rays of Light may contribute very much to the power of the Agent by which they are refracted.

- Query 21

- And so if any one would suppose that Æther (like our Air) may contain Particles which endeavour to recede from one another (for I do not know what this Æther is) and that its Particles are exceedingly smaller than those of Air, or even than those of Light: The exceeding smallness of its Particles may contribute to the greatness of the force by which those Particles may recede from one another, and thereby make that Medium exceedingly more rare and elastick than Air, and by consequence exceedingly less able to resist the motions of projectiles, and exceedingly more able to press upon gross Bodies, by endeavouring to expand it self.

- Query 21

- To make way for the regular and lasting Motions of the Planets and Comets, it's necessary to empty the Heavens of all Matter, except perhaps some very thin Vapours, Steams or Effluvia, arising from the Atmospheres of the Earth, Planets and Comets, and from such an exceedingly rare Æthereal Medium ... A dense Fluid can be of no use for explaining the Phænomena of Nature, the Motions of the Planets and Comets being better explain'd without it. It serves only to disturb and retard the Motions of those great Bodies, and make the frame of Nature languish: And in the Pores of Bodies, it serves only to stop the vibrating Motions of their Parts, wherein their Heat and Activity consists. And as it is of no use, and hinders the Operations of Nature, and makes her languish, so there is no evidence for its Existence, and therefore it ought to be rejected. And if it be rejected, the Hypotheses that Light consists in Pression or Motion propagated through such a Medium, are rejected with it.

And for rejecting such a Medium, we have the authority of those the oldest and most celebrated philosophers of ancient Greece and Phoenicia, who made a vacuum and atoms and the gravity of atoms the first principles of their philosophy, tacitly attributing Gravity to some other Cause than dense Matter. Later Philosophers banish the Consideration of such a Cause out of natural Philosophy, feigning Hypotheses for explaining all things mechanically, and referring other Causes to Metaphysicks: Whereas the main Business of natural Philosophy is to argue from Phenomena without feigning Hypotheses, and to deduce Causes from Effects, till we come to the very first Cause, which certainly is not mechanical.- Query 28 : Are not all Hypotheses erroneous in which Light is supposed to consist of Pression or Motion propagated through a fluid medium?

- What is there in places empty of matter? and Whence is it that the sun and planets gravitate toward one another without dense matter between them? Whence is it that Nature doth nothing in vain? and Whence arises all that order and beauty which we see in the world? To what end are comets? and Whence is it that planets move all one and the same way in orbs concentrick, while comets move all manner of ways in orbs very excentrick? and What hinders the fixed stars from falling upon one another?

- Query 28 : Are not all Hypotheses erroneous in which Light is supposed to consist of Pression or Motion propagated through a fluid medium?

- The changing of bodies into light, and light into bodies, is very conformable to the course of Nature, which seems delighted with transmutations.

- Query 30 : Are not gross bodies and light convertible into one another, and may not bodies receive much of their activity from the particles of light which enter into their composition?

- It seems probable to me that God, in the beginning, formed matter in solid, massy, hard, impenetrable, moveable particles, of such sizes and figures, and with such other properties, and in such proportions to space, as most conduced to the end for which He formed them; and that these primitive particles, being solids, are incomparably harder than any porous bodies compounded of them, even so very hard as never to wear or break in pieces; no ordinary power being able to divide what God had made one in the first creation. While the particles continue entire, they may compose bodies of one and the same nature and texture in all ages: but should they wear away or break in pieces, the nature of things depending on them would be changed.

- Query 31 : Have not the small particles of bodies certain powers, virtues, or forces, by which they act at a distance, not only upon the rays of light for reflecting, refracting, and inflecting them, but also upon one another for producing a great part of the Phenomena of nature?

How these Attractions may be perform'd, I do not here consider. What I call Attraction may be perform'd by impulse, or by some other means unknown to me. I use that Word here to signify only in general any Force by which Bodies tend towards one another, whatsoever be the Cause. For we must learn from the Phaenomena of Nature what Bodies attract one another, and what are the Laws and Properties of the attraction, before we enquire the Cause by which the Attraction is perform'd, The Attractions of Gravity, Magnetism and Electricity, react to very sensible distances, and so have been observed by vulgar Eyes, and there may be others which reach to so small distances as hitherto escape observation; and perhaps electrical Attraction may react to such small distances, even without being excited by Friction

- Query 31 : Have not the small particles of bodies certain powers, virtues, or forces, by which they act at a distance, not only upon the rays of light for reflecting, refracting, and inflecting them, but also upon one another for producing a great part of the Phenomena of nature?

- As in Mathematicks, so in Natural Philosophy, the Investigation of difficult Things by the Method of Analysis, ought ever to precede the Method of Composition.

- Query 31

- By this way of Analysis we may proceed from Compounds to Ingredients, and from Motions to the Forces producing them; and in general, from Effects to their Causes, and from particular Causes to more general ones, till the Argument end in the most general. This is the Method of Analysis: and the Synthesis consists in assuming the Causes discover'd, and establish'd as Principles, and by them explaining the Phænomena proceeding from them, and proving the Explanations.

- Query 31

"Hypothesis explaining the Properties of Light" (1675)

[edit]- Article sent to Henry Oldenburg in 1675 but not published until Thomas Birch, "History of the Royal Society" (1757) Vol.3 pp. 247, 262, 272; as quoted in Nature (1893) Vol.48 p. 536

- Were I to assume an hypothesis, it should be this, if propounded more generally, so as not to assume what light is further than that it is something or other capable of exciting vibrations of the ether. First, it is to be assumed that there is an ethereal medium, much of the same constitution as air, but far rarer, subtiller, and more strongly elastic. ...In the second place, it is to be supposed that the ether is a vibrating medium, like air, only the vibrations much more swift and minute; those of air made by a man's ordinary voice succeeding at more than half a foot or a foot distance, but those of ether at a less distance than the hundredth-thousandth part of an inch. And as in air the vibrations are some larger than others, but yet all equally swift... so I suppose the ethereal vibrations differ in bigness but not in swiftness. ...In the fourth place, therefore, I suppose that light is neither ether nor its vibrating motion, but something of a different kind propagated from lucid bodies. They that will may suppose it an aggregate of various peripatetic qualities. Others may suppose it multitudes of unimaginable small and swift corpuscles of various sizes springing from shining bodies at great distances one after the other, but yet without any sensible interval of time. ...To avoid dispute and make this hypothesis general, let every man here take his fancy; only whatever light be, I would suppose it consists of successive rays differing from one another in contingent circumstances, as bigness, force, or vigour, like as the sands on the shore... and, further, I would suppose it diverse from the vibrations of the ether. ...Fifthly, it is to be supposed that light and ether mutually act upon one another. ...æthereal vibrations are therefore the best means by which such a subtile agent as light can shake the gross particles of solid bodies to heat them.

- And so, supposing that light impinging on a refracting or reflecting ethereal superficies puts it into a vibrating motion, that physical superficies being by the perpetual applause of rays always kept in a vibrating motion, and the ether therein continually expanded and compressed by turns, if a ray of light impinge on it when it is much compressed, I suppose it is then too dense and stiff to let the ray through, and so reflects it; but the rays that impinge on it at other times, when it is either expanded by the interval between two vibrations or not too much compressed and condensed, go through and are refracted.

- And now to explain colours. I suppose that as bodies excite sounds of various tones and consequently vibrations, in the air of various bignesses, so when rays of light by impinging on the stiff refracting superficies excite vibrations in the ether, these rays excite vibrations of various bignesses... therefore, the ends of the capillamenta of the optic nerve which front or face the retina being such refracting superficies, when the rays impinge on them they must there excite these vibrations, which vibrations (like those of sound in a trumpet) will run along the pores or crystalline pith of the capillamenta through the optic nerves into the sensorium (which light itself cannot do), and there, I suppose, affect the sense with various colours, according to their bigness and mixture—the biggest with the strongest colours, reds and yellows; the least with the weakest, blues and violets; middle with green; and a confusion of all with white, much after the manner, that in the sense of hearing, nature makes use of aereal vibrations of several bignesses to generate sounds of divers tones; for the analogy of nature is to be observed.

Board of Longitude

[edit]- One [method] is by a Watch to keep time exactly. But, by reason of the motion of the Ship, the Variation of Heat and Cold, Wet and Dry, and the Difference of Gravity in different Latitudes, such a watch hath not yet been made.

- Written in remarks to the 1714 Longitude committee; quoted in Longitude (1995) by Dava Sobel, p. 52 (i998 edition) ISBN 1-85702-571-7)

- A good watch may serve to keep a recconing at Sea for some days and to know the time of a Celestial Observ[at]ion: and for this end a good Jewel watch may suffice till a better sort of Watch can be found out. But when the Longitude at sea is once lost, it cannot be found again by any watch.

- Letter to Josiah Burchett (1721), quoted in Longitude (1995) by Dava Sobel, p. 60

A short Schem of the true Religion

[edit]

- Undated manuscript : Keynes Ms. 7: '"A short Schem of the true Religion'"

- Religion is partly fundamental & immutable partly circumstantial & mutable. The first was the Religion of Adam, Enoch, Noah, Abraham Moses Christ & all the saints & consists of two parts our duty towards God & our duty towards man or piety & righteousness, piety which I will here call Godliness & Humanity.

- Godliness consists in the knowledge love & worship of God, Humanity in love, righteousness & good offices towards man.

- Of Godliness.

- Atheism is so senseless & odious to mankind that it never had many professors. Can it be by accident that all birds beasts & men have their right side & left side alike shaped (except in their bowels) & just two eyes & no more on either side the face & just two ears on either side the head & a nose with two holes & no more between the eyes & one mouth under the nose & either two fore leggs or two wings or two arms on the sholders & two leggs on the hipps one on either side & no more? Whence arises this uniformity in all their outward shapes but from the counsel & contrivance of an Author? Whence is it that the eyes of all sorts of living creatures are transparent to the very bottom & the only transparent members in the body, having on the outside an hard transparent skin, & within transparent juyces with a crystalline Lens in the middle & a pupil before the Lens all of them so truly shaped & fitted for vision, that no Artist can mend them? Did blind chance know that there was light & what was its refraction & fit the eys of all creatures after the most curious manner to make use of it? These & such like considerations always have & ever will prevail with man kind to believe that there is a being who made all things & has all things in his power & who is therfore to be feared.

- Of Atheism

- Idolatry is a more dangerous crime because it is apt by the authority of Kings & under very specious pretenses to insinuate it self into mankind. Kings being apt to enjoyn the honour of their dead ancestors: & it seeming very plausible to honour the souls of Heroes & Saints & to believe that they can heare us & help us & are mediators between God & man & reside & act principally in the temples & statues dedicated to their honour & memory? And yet this being against the principal part of religion is in scripture condemned & detested above all other crimes. The sin consists first in omitting the service of the true God.

- Of Idolatry

- The other part of the true religion is our duty to man. We must love our neighbour as our selves, we must be charitable to all men for charity is the greatest of graces, greater then even faith or hope & covers a multitude of sins. We must be righteous & do to all men as we would they should do to us.

- Of Humanity

- Abel was righteous & Noah was a preacher of righteousness & by his righteousness he was saved from the flood. Christ is called the righteous & by his righteousness we are saved & except our righteousness exceed the righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees we shall not enter into the kingdome of heaven. Righteousness is the religion of the kingdom of heaven & even the property of God himself towards man. Righteousness & Love are inseparable for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law.

Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733)

[edit]- Published posthumously by his nephew Benjamin Smith - Full text at Wikisource. For background information on these quotations, see Isaac Newton's religious views

- The authority of Emperors, Kings, and Princes, is human. The authority of Councils, Synods, Bishops, and Presbyters, is human. The authority of the Prophets is divine, and comprehends the sum of religion, reckoning Moses and the Apostles among the Prophets; and if an Angel from Heaven preach any other gospel, than what they have delivered, let him be accursed. Their writings contain covenant between God and his people, with instructions for keeping this covenant; instances of God's judgments upon them that break it: and predictions of things to come. While the people of God keep the covenant they continue to be his people: when they break it they cease to be his people or church, and become the Synagogue of Satan, who say they are Jews and are not. And no power on earth is authorized to alter this covenant.

The predictions of things to come relate to the state of the Church in all ages: and amongst the old Prophets, Daniel is most distinct in order of time, and easiest to be understood: and therefore in those things which relate to the last times, he must be made the key to the rest.

- For understanding the Prophecies, we are, in the first place, to acquaint our-selves with the figurative language of the Prophets. This language is taken from the analogy between the world natural, and an empire or kingdom considered as a world politic. Accordingly, the whole world natural consisting of heaven and earth, signifies the whole world politic, consisting of thrones and people, or so much of it as is considered in the Prophecy: and the things in that world signify the analogous things in this. For the heavens, and the things therein, signify thrones and dignities, and those who enjoy them; and the earth, with the things thereon, the inferior people; and the lowest parts of the earth, called Hades or Hell, the lowest or most miserable part of them. Whence ascending towards heaven, and descending to the earth, are put for rising and falling in power and honor: rising out of the earth, or waters, and falling into them, for the rising up to any dignity or dominion, out of the inferior state of the people, or falling down from the same into that inferior state; descending into the lower parts of the earth, for descending to a very low and unhappy estate; speaking with a faint voice out of the dust, for being in a weak and low condition; moving from one place to another, for translation from one office, dignity, or dominion, to another; great earthquakes, and the shaking of heaven and earth, for the shaking of kingdoms, so as to distract or overthrow them; the creating a new heaven and earth, and the passing away of an old one, or the beginning and end of the world, for the rise and ruin of the body politic signified thereby.

- In the heavens, the Sun and Moon are, by interpreters of dreams, put for the persons of Kings and Queens; but in sacred Prophecy, which regards not single persons, the Sun is put for the whole species and race of Kings, in the kingdom or kingdoms of the world politic, shining with regal power and glory; the Moon for the body of the common people, considered as the King's wife; the Stars for subordinate Princes and great men, or for Bishops and Rulers of the people of God, when the Sun is Christ; light for the glory, truth, and knowledge, wherewith great and good men shine and illuminate others; darkness for obscurity of condition, and for error, blindness and ignorance; darkening, smiting, or setting of the Sun, Moon, and Stars, for the ceasing of a kingdom, or for the desolation thereof, proportional to the darkness; darkening the Sun, turning the Moon into blood, and falling of the Stars, for the same; new Moons, for the return of a dispersed people into a body politic or ecclesiastic.

- Yet sometimes vegetables and animals are, by certain epithets or circumstances, extended to other significations; as a Tree, when called the tree of life or of knowledge; and a Beast, when called the old serpent, or worshiped. When a Beast or Man is put for a kingdom, his parts and qualities are put for the analogous parts and qualities of the kingdom; as the head of a Beast, for the great men who precede and govern; the tail for the inferior people, who follow and are governed; the heads, if more than one, for the number of capital parts, or dynasties, or dominions in the kingdom, whether collateral or successive, with respect to the civil government; the horns on any head, for the number of kingdoms in that head, with respect to military power...

- When a man is taken in a mystical sense, his qualities are often signified by his actions, and by the circumstances of things about him. So a Ruler is signified by his riding on a beast; a Warrior and Conqueror, by his having a sword and bow; a potent man, by his gigantic stature; a Judge, by weights and measures... the affliction or persecution which a people suffers in laboring to bring forth a new kingdom, by the pain of a woman in labor to bring forth a man-child; the dissolution of a body politic or ecclesiastic, by the death of a man or beast; and the revival of a dissolved dominion, by the resurrection of the dead.

- The Prophecies of Daniel are all of them related to one another, as if they were but several parts of one general Prophecy, given at several times. The first is the easiest to be understood, and every following Prophecy adds something new to the former.

- Daniel was in the greatest credit amongst the Jews, till the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. And to reject his prophecies, is to reject the Christian religion. For this religion is founded upon his prophecy concerning the Messiah.

- Now in this vision of the Image composed of four Metals, the foundation of all Daniel's Prophecies is laid. It represents a body of four great nations, which should reign over the earth successively, viz. the people of Babylonia, the Persians, the Greeks, and the Romans. And by a stone cut out without hands, which fell upon the feet of the Image, and brake all the four Metals to pieces, and became a great mountain, and filled the whole earth; it further represents that a new kingdom should arise, after the four, and conquer all those nations, and grow very great, and last to the end of all ages.

- The fourth Beast was the empire which succeeded that of the Greeks, and this was the Roman. This beast was exceeding dreadful and terrible, and had great iron teeth, and devoured and brake in pieces, and stamped the residue with its feet; and such was the Roman empire. It was larger, stronger, and more formidable and lasting than any of the former. ...it became greater and more terrible than any of the three former Beasts. This Empire continued in its greatness till the reign of Theodosius the great; and then brake into ten kingdoms, represented by the ten horns of this Beast; and continued in a broken form, till the Ancient of days sat in a throne like fiery flame, and the judgment was set, and the books were opened, and the Beast was slain and his body destroyed, and given to the burning flames; and one like the son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of days, and received dominion over all nations, and judgment was given to the saints of the most high, and the time came that they possessed the kingdom.

- I beheld, saith Daniel, till the Beast was slain, and his body destroyed, and given to the burning flames. As concerning the rest of the Beasts, they had their dominion taken away: yet their lives were prolonged for a season and a time [Chap. vii. 11, 12.]. And therefore all the four Beasts are still alive, tho the dominion of the three first be taken away. The nations of Chaldea and Assyria are still the first Beast. Those of Media and Persia are still the second Beast. Those of Macedon, Greece and Thrace, Asia minor, Syria and Egypt, are still the third. And those of Europe, on this side Greece, are still the fourth.

- Now Daniel, considered the horns, and behold there came up among them another horn, before whom there were three of the first horns plucked up by the roots; and behold in this horn were eyes like the eyes of a man, and a mouth speaking great things,—and his look was more stout than his fellows,—and the same horn made war with the saints, and prevailed against them... and speak great words against the most High, and wear out the saints, and think to change times and laws... By its eyes it was a Seer; and by its mouth speaking great things and changing times and laws, it was a Prophet as well as a King. And such a Seer, a Prophet and a King, is the Church of Rome. A Seer, Επισκοπος, is a Bishop in the literal sense of the word; and this Church claims the universal Bishopric. With his mouth he gives laws to kings and nations as an Oracle; and pretends to Infallibility, and that his dictates are binding to the whole world; which is to be a Prophet in the highest degree.

- In a small book printed at Paris A.C. 1689, entitled, An historical dissertation upon some coins of Charles the great, Ludovicus Pius, Lotharius, and their successors stamped at Rome, it is recorded, that in the days of Pope Leo X, there was remaining in the Vatican, and till those days exposed to public view, an inscription in honour of Pipin the father of Charles the great, in these words... "That Pipin the pious was the first who opened a way to the grandeur of the Church of Rome, conferring upon her the Exarchate of Ravenna and many other oblations." ...the Pope [Stephen II] sent letters to Pipin, wherein he told him that if he came not speedily against the Lombards, pro data sibi potentia, alienandum fore à regno Dei & vita æterna, he should be excommunicated. Pipin therefore, fearing a revolt of his subjects, and being indebted to the Church of Rome, came speedily with an army into Italy, raised the siege, besieged the Lombards in Pavia, and forced them to surrender the Exarchate and region of Pentapolis to the Pope for a perpetual possession. Thus the Pope became Lord of Ravenna, and the Exarchate, some few cities excepted; and the keys were sent to Rome, and laid upon the confession of St. Peter, that is, upon his tomb at the high Altar, in signum veri perpetuique dominii, sed pietate Regis gratuita, as the inscription of a coin of Pipin hath it. This was in the year of Christ 755. And henceforward the Popes being temporal Princes, left off in their Epistles and Bulls to note the years of the Greek Emperors, as they had hitherto done.

- Upon Christmas-day, the people of Rome, who had hitherto elected their Bishop, and reckoned that they and their Senate inherited the rights of the ancient Senate and people of Rome, voted Charles their Emperor, and subjected themselves to him in such manner as the old Roman Empire and their Senate were subjected to the old Roman Emperors. The Pope [Leo III] crowned him, and anointed him with holy oil, and worshiped him on his knees after the manner of adoring the old Roman Emperors... The Emperor, on the other hand, took the following oath to the Pope: In nomine Christi spondeo atque polliceor, Ego Carolus Imperator coram Deo & beato Petro Apostolo, me protectorem ac defensorem fore hujus sanctæ Romanæ Ecclesiæ in omnibus utilitatibus, quatenùs divino fultus fuero adjutorio, prout sciero poteroque. The Emperor was also made Consul of Rome, and his son Pipin crowned King of Italy: and henceforward the Emperor styled himself: Carolus serenissimus, Augustus, à Deo coronatus, magnus, pacificus, Romæ gubernans imperium [Charles, most serene Augustus crowned by God, the great, peaceful emperor ruling the Roman empire], or Imperator Romanorum [Emperor of the Romans]; and was prayed for in the Churches of Rome. His image was henceforward put upon the coins of Rome: while the enemies of the Pope, to the number of three hundred Romans and two or three of the Clergy, were sentenced to death. The three hundred Romans were beheaded in one day in the Lateran fields: but the Clergymen at the intercession of the Pope were pardoned, and banished into France. And thus the title of Roman Emperor, which had hitherto been in the Greek Emperors, was by this act transferred in the West to the Kings of France.

- The Popes began also about this time to canonize saints, and to grant indulgences and pardons: and some represent that Leo III was the first author of all these things. It is further observable, that Charles the great, between the years 775 and 796, conquered all Germany from the Rhine and Danube northward to the Baltic sea, and eastward to the river Teis; extending his conquests also into Spain as far as the river Ebro: and by these conquests he laid the foundation of the new Empire; and at the same time propagated the Roman Catholic religion into all his conquests, obliging the Saxons and Huns who were heathens, to receive the Roman faith, and distributing his northern conquests into Bishoprics, granting tithes to the Clergy and Peter-pence to the Pope: by all which the Church of Rome was highly enlarged, enriched, exalted, and established.

- In the reign of the Greek Emperor Justinian, and again in the reign of Phocas, the Bishop of Rome obtained some dominion over the Greek Churches, but of no long continuance. His standing dominion was only over the nations of the Western Empire, represented by Daniel's fourth Beast.

- While this Ecclesiastical Dominion was rising up, the northern barbarous nations invaded the Western Empire, and founded several kingdoms therein, of different religions from the Church of Rome. But these kingdoms by degrees embraced the Roman faith, and at the same time submitted to the Pope's authority. The Franks in Gaul submitted in the end of the fifth Century, the Goths in Spain in the end of the sixth; and the Lombards in Italy were conquered by Charles the great A.C. 774. Between the years 775 and 794, the same Charles extended the Pope's authority over all Germany and Hungary as far as the river Theysse and the Baltic sea; he then set him above all human judicature, and at the same time assisted him in subduing the City and Duchy of Rome. By the conversion of the ten kingdoms to the Roman religion, the Pope only enlarged his spiritual dominion, but did not yet rise up as a horn of the Beast. It was his temporal dominion which made him one of the horns: and this dominion he acquired in the latter half of the eighth century, by subduing three of the former horns as above. And now being arrived at a temporal dominion, and a power above all human judicature, he reigned with a look more stout than his fellows, and times and laws were henceforward given into his hands, for a time times and half a time, or three times and an half; that is, for 1260 solar years, reckoning a time for a Calendar year of 360 days, and a day for a solar year. After which the judgment is to sit, and they shall take away his dominion, not at once, but by degrees, to consume, and to destroy it unto the end. And the kingdom and dominion, and greatness of the kingdom under the whole heaven shall, by degrees, be given unto the people of the saints of the most High, whose kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and all dominions shall serve and obey him.

- The second and third Empires, represented by the Bear and Leopard, are again represented by the Ram and He-Goat; but with this difference, that the Ram represents the kingdoms of the Medes and Persians from the beginning of the four Empires, and the Goat represents the kingdom of the Greeks to the end of them. By this means, under the type of the Ram and He-Goat, the times of all the four Empires are again described: I lifted up mine eyes, saith Daniel, and saw, and behold there stood before the river [Ulai] a Ram which had two horns, and the two horns were high, but one was higher than the other, and the higher came up last.

- The Vision of the Image composed of four Metals was given first to Nebuchadnezzar, and then to Daniel in a dream: and Daniel began then to be celebrated for revealing of secrets, Ezek. xxviii. 3. The Vision of the four Beasts, and of the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven, was also given to Daniel in a dream. That of the Ram and the He-Goat appeared to him in the day time, when he was by the bank of the river Ulay; and was explained to him by the prophetic Angel Gabriel. It concerns the Prince of the host, and the Prince of Princes: and now in the first year of Darius the Mede over Babylon, the same prophetic Angel appears to Daniel again, and explains to him what is meant by the Son of man, by the Prince of the host, and the Prince of Princes. The Prophecy of the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven relates to the second coming of Christ; that of the Prince of the host relates to his first coming: and this Prophecy of the Messiah, in explaining them, relates to both comings, and assigns the times thereof.

- And upon a wing of abominations he shall cause desolation, even until the consummation, and that which is determined be poured upon the desolate. The Prophets, in representing kingdoms by Beasts and Birds, put their wings stretched out over any country for their armies sent out to invade and rule over that country. Hence a wing of abominations is an army of false Gods: for an abomination is often put in scripture for a false God; as where Chemosh is called the abomination of Moab, and Molech the abomination of Ammon. The meaning therefore is, that the people of a Prince to come shall destroy the sanctuary, and abolish the daily worship of the true God, and overspread the land with an army of false gods; and by setting up their dominion and worship, cause desolation to the Jews, until the times of the Gentiles be fulfilled. For Christ tells us, that the abomination of desolation spoken of by Daniel was to be set up in the times of the Roman Empire, Matth. xxiv. 15.

- The times of the Birth and Passion of Christ, with such like niceties, being not material to religion, were little regarded by the Christians of the first age. They who began first to celebrate them, placed them in the cardinal periods of the year; as the annunciation of the Virgin Mary, on the 25th of March, which when Julius Cæsar corrected the Calendar was the vernal Equinox; the feast of John Baptist on the 24th of June, which was the summer Solstice; the feast of St. Michael on Sept. 29, which was the autumnal Equinox; and the birth of Christ on the winter Solstice, Dec. 25, with the feasts of St. Stephen, St. John and the Innocents, as near it as they could place them. And because the Solstice in time removed from the 25th of December to the 24th, the 23d, the 22d, and so on backwards, hence some in the following centuries placed the birth of Christ on Dec. 23, and at length on Dec. 20: and for the same reason they seem to have set the feast of St. Thomas on Dec. 21, and that of St. Matthew on Sept. 21. So also at the entrance of the Sun into all the signs in the Julian Calendar, they placed the days of other Saints; as the conversion of Paul on Jan. 25, when the Sun entered Aquarius; St. Matthias on Feb. 25, when he entered Pisces; St. Mark on Apr. 25, when he entered Taurus; Corpus Christi on May 26, when he entered Gemini; St. James on July 25, when he entered Cancer; St. Bartholomew on Aug. 24, when he entered Virgo; Simon and Jude on Oct. 28, when he entered Scorpio: and if there were any other remarkable days in the Julian Calendar, they placed the Saints upon them, as St. Barnabas on June 11, where Ovid seems to place the feast of Vesta and Fortuna, and the goddess Matuta; and St. Philip and James on the first of May, a day dedicated both to the Bona Dea, or Magna Mater, and to the goddess Flora, and still celebrated with her rites. All which shews that these days were fixed in the first Christian Calendars by Mathematicians at pleasure, without any ground in tradition; and that the Christians afterwards took up with what they found in the Calendars.

- Thus have we, in the Gospels of Matthew and John compared together, the history of Christ's actions in continual order during five Passovers. John is more distinct in the beginning and end; Matthew in the middle: what either omits, the other supplies. The first Passover was between the baptism of Christ and the imprisonment of John, John ii. 13. the second within four months after the imprisonment of John, and Christ's beginning to preach in Galilee, John iv. 35. and therefore it was either that feast to which Jesus went up, when the Scribe desired to follow him, Matth. viii. 19. Luke ix. 51, 57. or the feast before it. The third was the next feast after it, when the corn was eared and ripe, Matth, xii. 1. Luke vi. 1. The fourth was that which was nigh at hand when Christ wrought the miracle of the five loaves, Matth. xiv. 15. John vi. 4, 5. and the fifth was that in which Christ suffered, Matth. xx. 17. John xii. 1.

- Between the first and second Passover John and Christ baptized together, till the imprisonment of John, which was four months before the second. Then Christ began to preach, and call his disciples; and after he had instructed them a year, lent them to preach in the cities of the Jews: at the same time John hearing of the fame of Christ, sent to him to know who he was. At the third, the chief Priests began to consult about the death of Christ. A little before the fourth, the twelve after they had preached a year in all the cities, returned to Christ; and at the same time Herod beheaded John in prison, after he had been in prison two years and a quarter: and thereupon Christ fled into the desert for fear of Herod. The fourth Christ went not up to Jerusalem for fear of the Jews, who at the Passover before had consulted his death, and because his time was not yet come. Thenceforward therefore till the feast of Tabernacles he walked in Galilee, and that secretly for fear of Herod: and after the feast of Tabernacles he returned no more into Galilee, but sometimes was at Jerusalem, and sometimes retired beyond Jordan, or to the city Ephraim by the wilderness, till the Passover in which he was betrayed, apprehended, and crucified.

- John therefore baptized two summers, and Christ preached three. The first summer John preached to make himself known, in order to give testimony to Christ. Then, after Christ came to his baptism and was made known to him, he baptized another summer, to make Christ known by his testimony; and Christ also baptized the same summer, to make himself the more known: and by reason of John's testimony there came more to Christ's baptism than to John's. The winter following John was imprisoned; and now his course being at an end, Christ entered upon his proper office of preaching in the cities. In the beginning of his preaching he completed the number of the twelve Apostles, and instructed them all the first year in order to send them abroad. Before the end of this year, his fame by his preaching and miracles was so far spread abroad, that the Jews at the Passover following consulted how to kill him. In the second year of his preaching, it being no longer safe for him to converse openly in Judea, he sent the twelve to preach in all their cities: and in the end of the year they returned to him, and told him all they had done. All the last year the twelve continued with him to be instructed more perfectly, in order to their preaching to all nations after his death. And upon the news of John's death, being afraid of Herod as well as of the Jews, he walked this year more secretly than before; frequenting deserts, and spending the last half of the year in Judea, without the dominions of Herod.