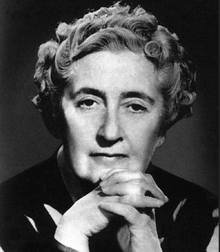

Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie (15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English author of detective fiction.

Quotes

[edit]

- I have given them life instead of death, freedom instead of the cords of superstition, beauty and truth instead of corruption and exploitation. The old bad days are over for them, the Light of the Aton has risen, and they can dwell in peace and harmony freed from the shadow of fear and oppression.

- Oh dear, I never realized what a terrible lot of explaining one has to do in a murder!

- Spider's Web (1956)

- I specialize in murders of quiet, domestic interest.

- LIFE magazine (14 May 1956)

The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920)

[edit]- This is the first story featuring "Hercule Poirot".

- The intense interest aroused in the public by what was known at the time as “The Styles Case” has now somewhat subsided. Nevertheless, in view of the world-wide notoriety which attended it, I have been asked, both by my friend Poirot and the family themselves, to write an account of the whole story. This, we trust, will effectually silence the sensational rumours which still persist.

- Captain Arthur Hastings, first paragraph

- The fellow is an absolute outsider, anyone can see that. He's got a great black beard, and wears patent leather boots in all weathers!

- “Ah!” Poirot shook his forefinger so fiercely at me that I quailed before it. “Beware! Peril to the detective who says: ‘It is so small — it does not matter. It will not agree. I will forget it.’ That way lies confusion! Everything matters.”

- Blood tells — always remember that — blood tells.

- Ah, my friend, one may live in a big house and yet have no comfort.

- You give too much rein to your imagination. Imagination is a good servant, and a bad master. The simplest explanation is always the most likely.

- Everything must be taken into account. If the fact will not fit the theory — let the theory go.

- “Tcha! Tcha!” cried Poirot irritably. “You argue like a child.”

- Now there is no murder without a motive.

- Yes, he is intelligent. But we must be more intelligent. We must be so intelligent that he does not suspect us of being intelligent at all.

- Two is enough for a secret.

- See you, one should not ask for outside proof — no, reason should be enough. But the flesh is weak, it is consolation to find that one is on the right track.

- “This affair must all be unravelled from within.” He tapped his forehead. “These little grey cells. It is ‘up to them’ — as you say over here.”

- Hercule Poirot

- Every murderer is probably somebody’s old friend.

- Hercule Poirot

- For Poirot, uttering a hoarse and inarticulate cry, again annihilated his masterpiece of cards and putting his hands over his eyes swayed backwards and forwards, apparently suffering the keenest agony.

“Good heavens Poirot!” I cried. “What is the matter? Are you taken ill?”

“No, no,” he gasped. “It is — it is — that I have an idea!”

- I am not keeping back facts. Every fact that I know is in your possession. You can draw your own deductions from them.

- Hercule Poirot

- I did not deceive you, mon ami. At most, I permitted you to deceive yourself.

- Hercule Poirot

- The happiness of one man and one woman is the greatest thing in all the world.

- "Nothing", I said sadly. "They are two delightful women!" "And neither of them is for you?" finished Poirot. "Never mind. Console yourself, my friend. We may hunt together again, who knows?"

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926)

[edit]

- Understand this, I mean to arrive at the truth. The truth, however ugly in itself, is always curious and beautiful to seekers after it.

- Hercule Poirot

- I have no pity for myself either. So let it be veronal. But I wish Hercule Poirot had never retired from work and come here to grow vegetable marrows.

- Doctor Sheppard

The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928)

[edit]- "Eh bien, Mademoiselle, all through my life I have observed one thing — 'All one wants one gets!' Who knows?" His face screwed itself up comically. "You may get more than you bargain for."

- Hercule Poirot

- I do not argue with obstinate men. I act in spite of them.

- Hercule Poirot

- “You have been to the Riviera before, Georges?” said Poirot to his valet the following morning.

George was an intensely English, rather wooden-faced individual.

“Yes, sir. I was here two years ago when I was in the service of Lord Edward Frampton.”

“And to-day,” murmured his master, “you are here with Hercule Poirot. How one mounts in the world!”

- Men are foolish, are they not, Mademoiselle? To eat, to drink, to breathe the good air, it is a very pleasant thing, Mademoiselle. One is foolish to leave all that simply because one has no money — or because the heart aches. L´amour, it causes many fatalities, does it not?

- Hercule Poirot

- I was wrong about that young man of yours. A man when he is making up to anybody can be cordial and gallant and full of little attentions and altogether charming. But when a man is really in love he can't help looking like a sheep. Now, whenever that young man looked at you he looked like a sheep. I take back all I said this morning. It is genuine.

- Miss Viner

- "I saw a particular personage and I threatened him — yes, Mademoiselle, I, Hercule Poirot, threatened him."

"With the police?"

"No," said Poirot drily, "With the Press — a much more deadly weapon."

- "Life is like a train Mademoiselle. It goes on. And it is a good thing that that is so."

"Why?"

"Because the train gets to its journey's end at last, and there is a proverb about that in your language, Mademoiselle."

"'Journeys end in lovers meeting'" Lenox laughed. "That is not going to be true for me."

"Yes — yes, it is true. You are young, younger than you yourself know. Trust the train Mademoiselle, for it is le bon Dieu who drives it".

Peril at End House (1932)

[edit]- I like to inquire into everything. Hercule Poirot is a good dog. The good dog follows the scent, and if, regrettably, there is no scent to follow, he noses around — seeking always something that is not very nice.

- Hercule Poirot

Murder on the Orient Express (1934)

[edit]- 1.2 The Tokatlian Hotel

- From a distance he had the bland aspect of a philanthropist.

- Précisément! The body — the cage — is everything of the most respectable — but through the bars, the wild animal looks out.

- 1.5 The Crime

- She shrugged her shoulders slightly.

“What can one do?”

“You are a philosopher, Mademoiselle.”

- 1.7 The Body

- See you, my dear doctor, me, I am not one to rely upon the expert procedure. It is the psychology I seek, not the fingerprint or the cigarette ash.

- 1.8 The Armstrong Kidnapping Case

- Tout de même, it is not necessary that he should be killed on the Orient Express. There are other places.

- 2.4 The Evidence of the American Lady

- “It makes me madder than a hornet to be disbelieved,” she explained.

- 2.5 The Evidence of the Swedish Lady

- “Me, I am convinced it is the truth,” said M. Bouc, becoming more and more enamoured of his theory.

- 2.9 The Evidence of Mr. Hardman

- “Do you always travel first-class, Mr. Hardman?”

“Yes, sir. The firm pays my travelling expenses.”

He winked.

- 2.10 The Evidence of the Italian

- I have the little idea, my friend, that this is a crime very carefully planned and staged. It is a far-sighted, long-headed crime. It is not — how shall I express it? — a Latin crime. It is a crime that shows traces of a cool, resourceful, deliberate brain — I think an Anglo-Saxon brain.

- 2.12 The Evidence of the German Lady's Maid

- It was abominable — wicked. The good God should not allow such things. We are not so wicked as that in Germany.

- 2.13 Summary of the Passengers' Evidence

- The impossible cannot have happened, therefore the impossible must be possible in spite of appearances.

- Hercule Poirot

- 2.15 The Evidence of the Passengers' Luggage

- Mon ami, if you wish to catch a rabbit you put a ferret into the hole, and if the rabbit is there he runs. That is all I have done.

- 3.5 The Christian Name of Princess Dragomiroff

- If you confront anyone who has lied with the truth, they usually admit it — often out of sheer surprise. It is only necessary to guess right to produce your effect.

- 3.7 The Identity of Mary Debenham

- “I like to see an angry Englishman,” said Poirot. “They are very amusing. The more emotional they feel the less command they have of language.”

- Exactly! It is absurd — improbable — it cannot be. So I myself have said. And yet, my friend, there it is! one cannot escape from the facts.

- Hercule Poirot

Death in the Clouds (1935)

[edit]- Ch. 11 The American

- But how much are the delicate convolutions of the brain influenced by the digestive apparatus? When the mal de mere seizes me I, Hercule Poirot, am a creature with no grey cells, no order, no method — a mere member of the human race somewhere below average intelligence!

- ‘Yes, my friend,’ he said. ‘It is so easy to be an American — here in Paris! A nasal voice — the chewing gum — the little goatee — the horned-rimmed spectacles — all the appurtenances of the stage American…’

- Ch. 13 At Antoine's

- An Englishman thinks first of his work — his job, he calls it — and then of his sport, and last — a good way last — of his wife.

- Ch. 15 In Bloomsbury

- Yes, a private investigator like my Wilbraham Rice. The public have taken very strongly to Wilbraham Rice. He bites his nails and eats a lot of bananas. I don't know why I made him bite his nails to start with — it's really rather disgusting — but there it is. He started by biting his nails, and now he has to do it in every single book. So monotonous.

- Ch. 16 Plan of Campaign

- ‘If one approaches a problem with order and method there should be no difficulty in solving it — none whatever,’ said Pirot severely.

- Ch. 21 The Three Clues

- There is no such thing as muddle — obscurity, yes — but muddle can exist only in a disorderly brain.

- Ch. 22 Jane Takes a New Job

- Ah, but it is incredible how often things force one to do the thing one would like to do.

- Poirot twinkled at her gently.

- Ch. 25 ‘I am Afraid’

- One has occasionally to pocket one's pride and readjust one's ideas.

- Ch. 26 After Dinner Speech

- I have, perhaps, too professional a point of view where deaths are concerned. They are divided, in my mind, into two classes — deaths which are my affair and deaths which are not my affair — and though the latter class is infinitely more numerous — nevertheless whenever I come in contact with death I am like the dog who lifts his head and sniffs the scent.

The ABC Murders (1936)

[edit]- Crime is terribly revealing. Try and vary your methods as you will, your tastes, your habits, your attitude of mind, and your soul is revealed by your actions.

- "This is M. Hercule Poirot," I said. Megan Barnard gave him a quick, appraising glance. "I've heard of you," she said. "You're the fashionable private sleuth, aren't you?". "Not a pretty description - but it suffices," said Poirot.

- Hercule Poirot once taught me in a very dramatic manner that romance can be a by-product of crime.

- Captain Arthur Hastings

Murder in Mesopotamia (1936)

[edit]- I don't pretend to be an author or to know anything about writing. I'm doing this simply because Dr Reilly asked me to, and somehow when Dr Reilly asks you to do a thing you don't like to refuse.

- Amy Leatheran

- That was the worst of Dr Reilly. You never knew whether he was joking or not. He always said things in the same slow melancholy way — but half the time there was a twinkle underneath it.

- Amy Leatheran

- Believe me, nurse, the difficulty of beginning will be nothing to the difficulty of knowing how to stop. At least that's the way it is with me when I have to make a speech. Someone's got to catch hold of my coat-tails and pull me down by main force.

- Dr Reilly

- God bless my soul, woman, the more personal you are the better! This is a story of human beings — not dummies! Be personal — be prejudiced — be catty — be anything you please! Write the thing your own way. We can always prune out the bits that are libellous afterwards!

- Dr Reilly

- I don't think I shall ever forget my first sight of Hercule Poirot. Of course, I got used to him later on, but to begin with it was a shock, and I think everyone else must have felt the same! I don't know what I'd imagined — something like Sherlock Holmes — [...] Of course, I knew he was a foreigner, but I hadn't expected him to be quite as foreign as he was, if you know what I mean. When you saw him you just wanted to laugh! He was like something on the stage or at the pictures. [...] He looked like a hairdresser in a comic play!

- Amy Leatheran

- I felt that the murderer was in the room. Sitting with us — listening. one of us

- Amy Leatheran

- Oh, dear, it's quite true what Dr. Reilly said. How does one stop writing? If I could find a really good telling phrase... Like the one M. Poirot used. In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate... Something like that.

- Amy Leatheran

Death on the Nile (1937)

[edit]- “Darling,” she drawled, “won’t that be rather tiresome? If any misfortunes happen to my friends I always drop them at once! It sounds heartless, but it saves such a lot of trouble later!”

- How true is the saying that man was forced to invent work in order to escape the strain of having to think.

- “There’s no reason why women shouldn’t behave like rational beings,” said Simon stolidly.

Poirot said dryly:

“Quite frequently they do. That is even more upsetting!”

- But to succeed in life every detail should be arranged well beforehand.

- It was a very British and utterly unconvincing performance.

- “You do well. Method and order, they are everything,” replied Poirot.

- I'm used to that. It often seems to me that's all detective work is — wiping out your false starts and beginning again.

- “That’s all very well — they’re not educated, poor creatures.”

“No, and a good thing too. Education has devitalised the white races. Look at America — goes in for an orgy of culture. Simply disgusting.”

- Once I went professionally to an archaeological expedition--and I learnt something there. In the course of an excavation, when something comes up out of the ground, everything is cleared away very carefully all around it. You take away the loose earth, and you scrape here and there with a knife until finally your object is there, all alone, ready to be drawn and photographed with no extraneous matter confusing it. That is what I have been seeking to do--clear away the extraneous matter so that we can see the truth--the naked shining truth.

- Hercule Poirot

- “It’s so dreadfully easy — killing people… And you begin to feel that it doesn’t matter… That it’s only you that matters! It’s dangerous — that.”

- And Mr. Burnaby said acutely: "Well, it doesn't seem to have done her much good, poor lass." But after a while they stopped talking about her and discussed instead who was going to win the Grand National. For, as Mr. Ferguson was saying at that minute in Luxor, it is not the past that matters but the future.

Murder for Christmas (1939, Holiday for Murder, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas)

[edit]- Pilar sat squeezed up against the window and thought how very odd the English smelt.

- “Pilar — remember — nothing is so boring as devotion.”

- “Yes, Mr. Lee.” Superintendent Sugden did not wast time on explanations. “What’s all this?”

- The character of the victim has always something to do with his or her murder.

- He is like a cat. And all cats are thieves.

- “Yes. I like to see people get angry. I like it very much. But here in England they do not get angry like they do in Spain. In Spain they take out their knives and they curse and shout. In England they do nothing, just get very red in the face and shut up their mouths tight.”

- “I agree with you. It is here a family affair. It is a poison that works in the blood — it is intimate — it is deep-seated. There is here, I think, hate and knowledge…”

- The crime is now logical and reasonable.

Sad Cypress (1940)

[edit]Elinor was still staring at this missive, her plucked brows drawn together in distaste, when the door opened. The maid announced, "Mr Welman," and Roddy came in.

Roddy! As always when she saw Roddy, Elinor was conscious of a slightly giddy feeling, a throb of sudden pleasure, a feeling that it was incumbent upon her to be very matter-of-fact and unemotional. Because it was so very obvious that Roddy, although he loved her, didn't feel about her the way she felt about him. The first sight of him did something to her, twisted her heart round so that it almost hurt. Absurd that a man - an ordinary, yes, a perfectly ordinary young man - should be able to do that to one! That the mere look of him should set the world spinning, that his voice should make you want - just a little - to cry. Love surely should be a pleasurable emotion - not something that hurt you by its intensity.

One thing was clear: one must be very, very careful to be off-hand and casual about it all. Men didn't like devotion and adoration. Certainly Roddy didn't.

N or M? (1941)

[edit]- Ch. 1

- There is always something about conscious tact that is very irritating.

- Is it coding — or code breaking? Is it like Deborah's job? Do be careful, Tommy, people go queer doing that and can't sleep and walk about all night groaning and repeating 978345286 or something like that and finally have nervous breakdowns and go into homes.

- Ch. 4

- ‘I have often noticed that being a devoted wife saps the intellect,’ murmured Tommy.

- Ch. 6

- ‘Truth of it is,’ said Commander Haydock, steering rather erratically round a one-way island and narrowly missing collision with a large van, ‘when the beggars are right, one remembers it, and when they’re wrong you forget it.’

- Ch. 7

- Flattery, in Tuppence's opinion, should always be laid on with a trowel where a man is concerned.

- Ch. 11

- ‘You’re frightfully BBC in your language this afternoon, Albert,’ said Tuppance, with some exasperation.

Albert looked slightly taken aback and reverted to a more natural form of speech.

‘I was listening to a very interesting talk on pond life last night,’ he explained.

- Ch. 12

- Like most Englishmen, he felt something strongly, and proceeded to muddle around until he had, somehow or other, cleared up the mess.

The Moving Finger (1942)

[edit]- Ch. 1

- I could think of nothing more insufferable than members of one's own gang dropping in full of sympathy and their own affairs.

- Ch. 4

- Freckles are so earnest and Scottish.

- Ch. 5

- Quite absurd, because Caleb has absolutely no taste for fornication. He never has had. So lucky, being a clergyman.

- Ch. 6

- Work, Mr. Burton. There's nothing like work, for men and women. The one unforgivable sin is idleness.

- Ch. 7

- “Jerry had an expensive public school education, so he doesn’t recognize Latin when he hears it,” said Joanna

- Ch. 10

- To commit a successful murder must be very much like bringing off a conjuring trick.

- Ch. 12

- “It makes her rather alarming,” I said.

“Sincerity has that effect,” said Miss Marple.

- Ch. 14

- Miss Marple twinkled at me.

Towards Zero (1944)

[edit]- Last time I had my hands on you, you felt like a bird - struggling to escape. You'll never escape now...

- MacWhirter

Death Comes as the End (1945)

[edit]- Because, Renisenb, it is so easy and it costs so little labour to write down ten bushels of barley, or a hundred head of cattle, or ten fields of spelt - and the thing that is written will come to seem like the real thing, and so the writer and the scribe will come to despise the man who ploughs the fields and reaps the barley and raises the cattle - but all the same the fields and the cattle are real - they are not just marks of inks on papyrus. And when all the records and all the papyrus rolls are destroyed and the scribes are scattered, the men who toil and reap will go on, and Egypt will still live.

- Hori

- "You know that in all tombs there is always a false door?"

Renisenb stared. "Yes, of course."

"Well, people are like that too. They create a false door - to deceive. If they are conscious of weakness, of inefficiency, they make an imposing door of self-assertion, of bluster, of overwhelming authority - and, after a time, they get to believe in it themselves. They think, and everybody thinks, that they are like that. But behind that door, Renisenb, is a bare rock … And so when reality comes and touches them with the feather of truth - their true self reasserts itself."

- "It is the kind of thing that happens to you when you are stupid," said Esa. "Things go entirely differently from the way you planned them."

- Courage is the resolution to face the unforeseen.

- Fear is incomplete knowledge.

- The rottenness comes from within.

- Let us think only of the good days that are to come.

- It's as easy to utter lies as truth.

- Men are made fools by the gleaming limbs of women, and, lo, in a minute they are become discolored carnelians. A trifle, a little, the likeness of a dream. And death comes as the end.

- Proof must be solid break walls of facts.

- Handsome, strong, gay ... She felt again the thro and lilt of her blood. She had loved Kameni in that moment. She loved him now. Kameni could take the place that Khay had held in her life. She thought: "We shall be happy together - yes, we shall be happy. We shall live together and take pleasure in each other and we shall have strong, handsome children. There will be busy days full of work … and days of pleasure when we sail on the River...Life will be again as I knew it with Khay...What could I ask more than that? What do I want more than that?"

- When you were a child, I loved you. I loved your grave face and the confidence with which you came to me, asking me to mend your broken toys. And then, after eight years' absence, you came again and sat here, and brought me the thoughts that were in your mind. And your mind, Renisenb, is not like the minds of the rest of your family. It does not turn in upon itself, seeking to encase itself in narrow walls. Your mind is like my mind, it looks over the River, seeing a world of changes, of new ideas - seeing a world where all things are possible to those with courage and vision...

- Hori

- She broke off, unable to find words to frame her struggling thoughts. What life would be with Hori, she did not know. In spite of his gentleness, in spite of his love for her, he would remain in some respects incalculable and incomprehensible. They would share moments of great beauty and richness together - but what of their common daily life?

- "I have made my choice, Hori. I will share my life with you for good or evil, until death comes..." With his arms round her, with the sudden new sweetness of his face against hers, she was filled with an exultant richness of living.

The Hollow (1946)

[edit]- I must have a talk with you, David, and learn all the new ideas. As far as I can see, one must hate everybody but at the same time give them free medical attention and a lot of extra education, poor things! All those helpless little children herded into schoolhouses every day — and cod liver oil forced down babies' throats whether they like it or not — such nasty-smelling stuff.

- Lucy Angkatell

- John, forgive me... for what I can't help doing.

- Henrietta Savernake

- And if you cast down an idol, there's nothing left.

- Henrietta Savernake

A Murder is Announced (1950)

[edit]

- I think perhaps it wasn't a good idea to read aloud Gibbon to me in the evenings, because if it's nice and hot by the fire, there's something about Gibbon that does, rather, make you go to sleep.

- It's so messy bleeding like a pig.

- He could have shot her from behind a hedge in the good old Irish fashion and probably got away with it.

- “I am not very clever about Americanisms — and I understand they change very quickly.”

- Perhaps a little of Trollope, but not to drown in him.

- “I always feel that the young doctors are only too anxious to experiment. After they’ve whipped out all our teeth, and administered quantities of very peculiar glands, and removed bits of our insides, they then confess that nothing can be done for us. I really prefer the old-fashioned remedy of big black bottles of medicine. After all, one can always pour those down the sink.”

- “No,” said Miss Marple. “Murder isn’t a game.

- Weak and kindly people are often very treacherous. And if they’ve got a grudge against life it saps the little moral strength that they may possess.

- One forgets how human murderers are.

- It all came together then, you see — all the various isolated bits — and made a coherent pattern.

After the Funeral (1953)

[edit]- What any woman saw in some particular man was beyond the comprehension of the average intelligent male. It just was so. A woman who could be intelligent about everything else in the world could be a complete fool when it came to some particular man.

- Any medical man who predicts exactly when a patient will die, or exactly how long he will live, is bound to make a fool of himself. The human factor is always incalculable. The weak have often unexpected powers of resistance, the strong sometimes succumb.

- There were to be no short cuts to the truth. Instead he would have to adopt a longer, but a reasonably sure method. There would have to be conversation. Much conversation. For in the long run, either through a lie, or through truth, people were bound to give themselves away...

- How averse human beings were ever to admit ignorance!

- Men always tell such silly lies.

- It shows you, Madame, the dangers of conversation. It is a profound belief of mine that if you can induce a person to talk to you for long enough, on any subject whatever, sooner or later they will give themselves away.

A Pocket Full of Rye (1953)

[edit]- The tear rose in Miss Marple's eyes. Succeeding pity, there came anger - anger against a heartless killer. And then, displacing both these emotions, there came a surge of triumph - the triumph some specialist might feel who has successfully reconstructed an extinct animal from a fragment of jawbone and a couple of teeth.

The Burden (1956)

[edit]- Written under the pen name Mary Westmacott.

- “A dog,” said Mr. Baldock, in his lecture-room style, which was capable of rousing almost anybody to violent irritation, “has an extraordinary power of bolstering up the human ego.”

- “Here are my roses. Like ’em?”

“They’re beautiful,” said Laura politely.

“On the whole,” said Mr. Baldock, “I prefer them to human beings. They don’t last as long for one thing.”

- Children and one's social inferiors never know when to say good-bye. One has to say it for them.

- They have, all of them, such wonderful good manners. Not taught good manners — the natural thing. I could never have believed till I came here that natural courtesy could be such a wonderful — such a positive thing.

Dead Man's Folly (1956)

[edit]- I can imagine anything! That's the trouble with me. I can imagine things now — this minute. I could even make them sound all right, but of course none of them would be true.

- Ariadne Oliver

- It would be difficult Bland thought, to forget Hercule Poirot, and this not entirely for complimentary reasons.

The Pale Horse (1961)

[edit]- Ch. 1

- What else will you have? Nice banana and bacon sandwich?

- Ch. 4

- How convenient if you could ring up Harrods and say ‘Please send along two good murderers, will you?’

- Ch. 24

- What beats me — it always does — is how a man can be so clever and yet be such a perfect fool.

A Caribbean Mystery (1964)

[edit]- I have a certain experience of the way people tell lies.

At Bertram's Hotel (1965)

[edit]- "Well", said Miss Marple. "Are you going to let her get away with it?" There was a pause, then Father brought down his fist with a crash on the table. "No", he roared — "No, by God I'm not!" Miss Marple nodded her head slowly and gravely. "May God have mercy on her soul," she said.

Surprise! Surprise! (1965)

[edit]- Where There's a Will

- The reason he liked attending rich patients rather than poor ones was the he could exercise his active imagination in prescribing for their ailments.

- Greenshaw's Folly

- She came in with coffee and biscuits at half-past eleven with her mouth pursed up very prunes and prisms, and would hardly speak to me.

Third Girl (1966)

[edit]

- Ch. 8

- “Aha? You have been very clever, madame.”

“No, I haven’t really. It was a pure accident. I mean, I walked into a small café place and there the girl was, just sitting there.”

“Ah. You had the good fortune then. That is just as important.”

- The old, you must remember, though considered incapable of action, have nevertheless a good fund of experience on which to draw.

- Ch. 11

- It merely confirmed in him his long-held belief that you should never believe anything anyone said without first checking it. Suspect everybody, had been for many years, if not his whole life, one of his first axioms.

- Ch. 14

- Mrs. Oliver in her own opinion was famous for her intuition. One intuition succeeded another with remarkable rapidity, and Mrs. Oliver always claimed the right to justify the particular intuition which turned out to be right!

- Ch. 15

- It was the technique of a man who selected thoughts as one might select pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. In due course they would be reassembled together so as to make a clear and coherent picture. At the moment the important thing was the selection, the separation.

- Ch. 18

- “Well, what are you doing? What have you done?”

“I am sitting in this char,” said Poirot. “Thinking,” he added.

“Is that all?” said Mrs. Oliver.

“It is the important thing,” said Poirot.

- “Tout de même,” said Poirot, “since I cannot find anything, eh bien, then the logic falls out of the window.”

Endless Night (1967)

[edit]

- In my end is my beginning — that's what people are always saying. But what does it mean? And just where does my story begin? I must try and think...

- Michael Rogers (the narrator)

The Labours of Hercules (1967)

[edit]- Forward

- Without interest (hers not the type to wonder why!) but with perfect efficiently, Miss Lemon had fulfilled her task.

- Take this Hercules — this hero! Hero, indeed! What was he but a large muscular creature of low intelligence and criminal tendencies!

- Ch. 1 The Nemean Lion

- “I — I don’t regret what I did. I think that you are a kind man, Mr. Poirot, and that possibly you might understand. You see, I’ve been so terribly afraid.”

“Afraid?”

“Yes, it’s difficult for a gentleman to understand, I expect. But you see, I’m not a clever woman at all, and I’ve no training and I’m getting older — and I’m so terrified for the future. I’ve not been able to save anything — how could I with Emily to be cared for? — and as I get older and more incompetent there won’t be any one who wants me. They’ll want somebody young and brisk. I’ve — I’ve known so many people like I am — nobody wants you and you live in a one room and you can’t have a fire or any warmth and not very much to eat and at last you can’t even pay the rent on your room … There are Institutions, of course, but it’s not very easy to get into them unless you have influential friends, and I haven’t. There are a good many others situated like I am — poor companions — untrained useless women with nothing to look forward to but a deadly fear…”

- Ch. 2 The Lernean Hydra

- Even the sensible and the competent have been given tongues by le bon Dieu — and they do not always employ their tongues wisely.

- Ch. 3 The Arcadian Deer

- He had not remembered her name, but he had seen her dance — had been carried away and fascinated by the supreme art that can make you forget art.

- Ch. 4 The Erymanthian Boar

- On the seat opposite him was an American tourist. The pattern of his clothes, of his overcoat, the grip he carried, down to his hopeful friendliness and his naïve absorption in the scenery, even the guidebook in his hand, all gave him away and proclaimed him a small town American seeing Europe for the first time. In another minute or so, Poirot judged, he would break into speech. His wistful dog-like expression could not be mistaken.

- And then, startling in its crisp transatlantic tones, a voice said:

“Stick ’em up.”

They swerved around. Schwartz, dressed in a peculiarly vivid set of striped pyjamas stood in the doorway. In his hand he held an automatic.

“Stick ’em up, guys. I’m pretty good at shooting.”

He pressed the trigger — and a bullet sang past the big man's ear and buried itself in the woodwork of the window.

Three pairs of hands were raised rapidly.

- Ch. 5 The Augean Stables

- Words had become to him a means of obscuring facts — not of revealing them. He was an adept in the art of the useful phrase — that is to say the phrase that falls soothingly on the ear and is quite empty of meaning.

- Ch. 6 The Stymphalean Birds

- Harold Waring, like many other Englishmen, was a bad linguist.

- Ch. 11 The Apples of the Hesperides

- “Is he then an unhappy man?”

Poirot said:

“So unhappy that he has forgotten what happiness means. So unhappy that he does not know he is unhappy.”

The nun said softly:

“Ah, a rich man…”

- Ch. 12 The Capture of Cerberus

- It is the misfortune of small, precise men always to hanker after large and flamboyant women.

Hallowe'en Party (1969)

[edit]- I know there’s a proverb which says, “To err is human” but a human error is nothing to what a computer can do if it tries.

- Ariadne Oliver

Hercule Poirot’s Early Cases (1974)

[edit]- The Lost Mine

- But when investing money, keep, I beg of you, Hastings, strictly to the conservative.

- The Plymouth Express

- They are so busy knocking that they do not notice that the door is open!

- The Chocolate Box

- Remember, he was a fanatic, and there is no fanatic like a religious fanatic.

- Never mind. I knew — that was the great thing.

- “Mademoiselle,” I said, “it is sometimes difficult for a dog to find a scent, but once he has found it, nothing on earth will make him leave it! That is if he is a good dog! And I, mademoiselle, I, Hercule Poirot, am a very good dog.”

- Double Sin

- Never do I deceive you, Hastings. I only permit you to deceive yourself.

- Wasps' Nest

- “The English are very stupid,” said Poirot. “They think that they can deceive anyone but that no one can deceive them.”

- The Veiled Lady

- You have an excellent heart, my friend — but your grey cells are in a deplorable condition.

Curtain - Poirot's Last Case (1975)

[edit]- Who is there who has not felt a sudden startled pang at reliving an old experience or feeling an old emotion?

- First line

- Not if the butcher had become a butcher simply in order to have a chance of murdering the baker. One must always look one step behind, my friend.

- I aroused Judith's contempt by asking what good all this was likely to do to mankind? There is no question that annoys your true scientist more.

- This, Hastings, will be my last case. It will be, too, my most interesting case — and my most interesting criminal.

- Hercule Poirot

- I have no more now to say. I do not know, Hastings, if what I have done is justified or not justified. No — I do not know. I do not believe that a man should take the law into his own hands... But on the other hand, I am the law! As a young man in the Belgian police force I shot down a desperate criminal who sat on a roof and fired at people below. In a state of emergency martial law is proclaimed.

- I have always been so sure — too sure... But now I am very humble and I say like a little child: "I do not know..."

- Hercule Poirot

- We shall not hunt together again, my friend. Our first hunt was here — and our last ... They were good days, Yes, they have been good days...

- Hercule Poirot

Sleeping Murder (1976)

[edit]- Ch. 1 A House

- Plymouth, Gwenda thought, as she moved forward obediently in the queu for Passports and Customs, was probably not the best of England.

- Ch. 4 Helen?

- Well, of course, Gwenda dear, you can always do that when you've exhausted every other line of approach, but I always think myself it's better to examine the simplest and most commonplace explanations first.

- It's not impossible my dear. It's just a very remarkable coincidence — and remarkable coincidences do happen.

- These little things are very significant.

- Ch. 5 Murder in Retrospect

- Murder isn't — it really isn't — a thing to tamper with lightheartedly.

- Ch. 25 Postscript at Torquay

- It really is very dangerous to believe people. I never have for years.

An Autobiography (1977)

[edit]

The whole Agatha, so I believe, is known only to God.

- Life seems to me to consist of three parts: the absorbing and usually enjoyable present which rushes on from minute to minute with fatal speed; the future, dim and uncertain, for which one can make any number of interesting plans, the wilder and more improbable the better, since — as nothing will turn out as you expect it to do — you might as well have the fun of planning anyway; and thirdly, the past, the memories and realities that are the bedrock of one's present life, brought back suddenly by a scent, the shape of a hill, an old song — some triviality that makes one suddenly say "I remember…" with a peculiar and quite unexplainable pleasure.

- Foreword

- What governs one's choice of memories? Life is like sitting in a cinema. Flick! Here am I, a child eating éclairs on my birthday. Flick!

Two years have passed and I am sitting on my grandmother's lap, being solemnly trussed up as a chicken just arrived from Mr Whiteley's, and almost hysterical with the wit of the joke.

Just moments — and in between long empty spaces of months or even years.- Foreword

- We never know the whole man, though sometimes, in quick flashes, we know the true man. I think, myself, that one's memories represent those moments which, insignificant as they may seem, nevertheless represent the inner self and oneself as most really oneself.

I am today the same person as that solemn little girl with pale flaxen sausage-curls. The house in which the spirit dwells, grows, develops instincts and tastes and emotions and intellectual capacities, but I myself, the true Agatha, am the same. I do not know the whole Agatha.

The whole Agatha, so I believe, is known only to God.- Foreword

- To be part of something one doesn't in the least understand is, I think, one of the most intriguing things about life.

I like living. I have sometimes been wildly despairing, acutely miserable, racked with sorrow, but through it all I still know quite certainly that just to be alive is a grand thing.- Foreword

- One of the luckiest things that can happen to you in life is to have a happy childhood. I had a very happy childhood. I had a home and a garden that I loved; a wise and patient Nanny; as father and mother two people who loved each other dearly and made a success of their marriage and of parenthood.

Looking back I feel that our house was truly a happy house. That was largely due to my father, for my father was a very agreeable man.- Part I: Ashfield, §I

- The quality of agreeableness Is not much stressed nowadays. People tend to ask if a man is clever, industrious, if he contributes to the well-being of the community, if he ‘counts’ in the scheme of things.

- Part I: Ashfield, §I

- Servants, of course, were not a particular luxury–it was not a case of only the rich having them; the only difference was that the rich had more.

- Part I: Ashfield, §III

- We had three servants, which was a minimum then.

- Part I: Ashfield, §IV

- I don't think necessity is the mother of invention — invention, in my opinion, arises directly from idleness, possibly also from laziness. To save oneself trouble.

- Part III: Growing Up, §II

- Looking back, it seems to me extraordinary that we should have contemplated having both a nurse and a servant, but they were considered essentials of life in those days, and were the last things we would have thought of dispensing with. To have committed the extravagance of a car, for instance, would never have entered our minds. Only the rich had cars.

- Part V: War, §IV

Disputed

[edit]- An archaeologist is the best husband any woman can have; the older she gets, the more interested he is in her.

- Christie denied having made this remark, which had been attributed to her by her second husband Sir Max Mallowan in a news report (9 March 1954); according to Nigel Dennis, "Genteel Queen of Crime: Agatha Christie Puts Her Zest for Life Into Murder", Life, Volume 40, N° 20, 14 May 1956, she was quoting "a witty wife"; Quote Investigator reports on "An Archaeologist Is the Best Husband a Woman Can Have" as of uncertain origin.

Misattributed

[edit]- It is ridiculous to set a detective story in New York City. New York City is itself a detective story.

- This is in fact something an admirer said, which Christie quoted with disapproval in LIFE magazine (14 May 1956), p. 98

Quotes about Agatha Christie

[edit]- I loved mysteries and read all of Agatha Christie and Conan Doyle.

- Alongside politicians and the press, writers of fiction picked up the theme of a sinister Communist threat, a theme that drew on the intelligence wars between the Soviet Union and the West. John Buchan, a Scottish novelist who had served in intelligence during World War One before becoming an MP, saw the hidden hand of a Communist plot to take over the world. In her novel The Big Four (1927), Agatha Christie, a successful British novelist, referred to ‘the world-wide unrest, the labour troubles that beset every nation, and the revolutions that break out in some’. The sense of menace played an important role in imaginative fiction. It took forward the pre-war strand of spy fiction, but added a theme of social disorder. There was also frequently a racial dimension, with a tendency to depict hostile figures as Slav and Jewish, frequently in league with sinister elements in British (or French or American) society. This theme drew on a broader hostility to Jews that was given renewed energy by the association of the Russian Revolution in hostile eyes with them. Russian émigrés spread this assessment. In turn, there was similar material in the Soviet Union about Western plots to overthrow the Revolution, a theme that long continued.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- It is well-known that Agatha Christie was not so much a novelist as the inventor of a novelty, a peculiarly intricate and entertaining type of puzzle. All the complexity and originality she could muster went into the construction of the story; her characters, apart from a handful of principals, are rarely more than cyphers.

- Patricia Craig and Mary Cadogan, The Lady Investigates: Women Detectives and Spies in Fiction (1986), p. 166

- Until about 1957, Agatha Christie's plots were ingeniously composed of interlocking segments. This was the area in which she excelled; her tone and style have always been less satisfactory. The former is often whimsical or sententious, the latter unremittingly bland. She was involved in the delineation of a world of safety and complacence where the precise moment of a misdeed could be established by reference to an unfailing custom.

- Patricia Craig and Mary Cadogan, The Lady Investigates: Women Detectives and Spies in Fiction (1986), p. 167

- If Agatha Christie the detective writer can be said to have taken characters out of a box, here in a few pages she shows how deftly she could bring individuals to life.

- Jacquetta Hawkes, 'Introduction' to Agatha Christie, Come, Tell Me How You Live (1983), p. 11

- Above all she is a literary conjuror who places her pasteboard characters face downwards and shuffles them with practised cunning.

- P. D. James, Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), p. 98

- Perhaps her greatest strength was that she never overstepped the limits of her talent. She knew precisely what she could do and she did it well... Her prime skill as a storyteller is the talent to deceive.

- P. D. James, Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), pp. 98-99

- On vacations, I will take a giant stack of Agatha Christie novels and read one every day. I never remember who this killer is, even when I've read it before, and I always have to stay up to finish because I HAVE TO FIND OUT. I don’t know how she does it.

- Celeste Ng interview (2022)

- I do not know anyone who has, in such a supreme degree, what I would call Mrs. Christie's despatch. She wields her humane-killer with a butcher-like indifference to life; her murders are clean, explicit, feline. "But above the ear was a tiny hole with an incrustation of dried blood round it." That is the typical Christie sentence for such occasions. It was almost Websterian. Her pistols seem poetic toys, the knives are surgical instruments; there is a housewifely neatness in the slaughterhouse. The very style is cut to pattern... She is neither too short nor too long, too tough nor too tender; she is energetic, decisive, and slightly catty where women are concerned.

- Herbert Read, 'Blood Wet and Dry', Night and Day (23 December 1937), quoted in Christopher Hawtree (ed.), Night and Day (1985), p. 269

- Will Agatha Christie plays stand the test of time like those of Somerset Maugham or Noel Coward? They may date, as indeed have Murder at the Vicarage, which has now been running for two years at the Savoy, and The Mousetrap, in its twenty-sixth year at St. Martin's. But they do recall a visual nostalgia for a middle-class way of life that will never return to England. Of spacious chintzy country houses, cultivated morning-room talk, impeccable servants, bowls of potpourri, croquet on the lawn, Earl Grey tea poured from Georgian silver, and wafer-thin brown bread cucumber sandwiches.

Perhaps this is what many of us are longing for.- Gwen Robyns, The Mystery of Agatha Christie (1979), pp. 219-220

- The people in Agatha Christie's books look back, more than those of any other modern writer, to the world of her childhood and adolescence, that time when social life was settled and people knew their places in it. Her love for Ashfield, the sizeable villa in Torquay where she grew up, is responsible for the many country houses in her books. She reflected late in her life that one of the things she would miss most, if she were a modern child, would be the absence of servants, and there are dozens of servants in her stories; butlers and housekeepers, housemaids and under-housemaids, gardeners and odd-job men... She was looking back always to a style of behaviour that had ended in 1914.

- Julian Symons, Critical Observations (1981), p. 142

- Such was England as represented by Mayhem Parva. It was, of course, a mythical kingdom, a fly-in-amber land. It was derived in part from the ways and values of a society that had begun to fade away from the very moment of the shots at Sarajevo; in part from that remarkably durable sentimentality which, even today, can be expressed in the proposition that every church clock has stopped at 14.50 hours and honey is a perpetual comestible at vicarages.

It offered not outward escape, as did books of travel, adventure, international intrigue, but inward – into a sort of museum of nostalgia.- Colin Watson, Snobbery with Violence: Crime Stories and Their Audience (1971), p. 171

External links

[edit]- 1890 births

- 1976 deaths

- Detective fiction authors

- Novelists from England

- Playwrights from England

- Poets from England

- Short story writers from England

- Autobiographers from the United Kingdom

- Memoirists from England

- Nurses

- Women from England

- Women authors

- Women born in the 19th century

- Christians from the United Kingdom

- Edgar Award winners