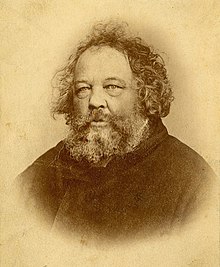

Mikhail Bakunin

Appearance

(Redirected from Bakunin)

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (Russian: Михаил Александрович Бакунин) (30 May 1814 – 1 July 1876) was a Russian political philosopher, anarchist, and noted atheist.

Quotes

[edit]

- FREEDOM, the realization of freedom: who can deny that this is what today heads the agenda of history? … Revolutionary propaganda is in its deepest sense the negation of the existing conditions of the State, for, with respect to its innermost nature, it has no other program than the destruction of whatever order prevails at the time.... We must not only act politically, but in our politics act religiously, religiously in the sense of freedom, of which the one true expression is justice and love. Indeed, for us alone, who are called the enemies of the Christian religion, for us alone it is reserved, and even made the highest duty … really to exercise love, this highest commandment of Christ and this only way to true Christianity.

- "The Reaction in Germany" (1842), Bakunin's first political writings, under the pseudonym "Jules Elysard"; it was not until 1860 that he began to publicly assert a stance of firm atheism and vigorous rejection of traditional religious institutions.

- Everywhere, especially in France and England, social and religious societies are being formed which are wholly alien to the world of present-day politics, societies that derive their life from new sources quite unknown to us and that grow and diffuse themselves without fanfare. The people, the poor class, which without doubt constitutes the greatest part of humanity; the class whose rights have already been recognized in theory but which is nevertheless still despised for its birth, for its ties with poverty and ignorance, as well as indeed with actual slavery – this class, which constitutes the true people, is everywhere assuming a threatening attitude and is beginning to count the ranks of its enemy, far weaker in numbers than itself, and to demand the actualization of the right already conceded to it by everyone. All people and all men are filled with a kind of premonition, and everyone whose vital organs are not paralyzed faces with shuddering expectation the approaching future which will utter the redeeming word. Even in Russia, the boundless snow-covered kingdom so little known, and which perhaps also has a great future in store, even in Russia dark clouds are gathering, heralding storm. Oh, the air is sultry and pregnant with lightning.

And therefore we call to our deluded brothers: Repent, repent, the Kingdom of the Lord is at hand!- "The Reaction in Germany" (1842)

- We exhort the compromisers to open their hearts to truth, to free themselves of their wretched and blind circumspection, of their intellectual arrogance, and of the servile fear which dries up their souls and paralyzes their movements.

Let us therefore trust the eternal Spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unfathomable and eternal source of all life. The passion for destruction is a creative passion, too! - Freemasonry, in its development, in its growing power at first and later in its decadence, represented in a way the development, power, and moral and intellectual decadence of the bourgeoisie. Today, fallen to the sad position of a senile old intriguer, it is a useless, sometimes malevolent and always ridiculous nullity, whereas, before 1830 and especially before 1793, having gathered together at its core, with very few exceptions, all the minds of the elite, the most ardent hearts, the proudest spirits, the most audacious personalities, it had constituted an active powerful, and truly beneficial institution. It was the energetic incarnation and implementation of the humanitarian ideal of the eighteenth century. All those great principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity, of reason and human justice, elaborated theoretically at first by the philosophy of that century, became in the hands of the Freemasons practical dogmas and the foundations of a new moral and political program, the soul of a gigantic enterprise of demolition and reconstruction. In that epoch, Freemasonry was nothing less than the universal conspiracy of the revolutionary bourgeoisie against the feudal monarchical and divine tyranny. It was the International of the bourgeoisie.

- "Letter to the Comrades of the International Workingmen's Association of Locle and Cheau-de-Fonds", (1869)

- I eagerly await tomorrow's mail to have news of Russia and Poland. For now, I have to content myself with a few vague rumors which float around. I have heard about new, bloody skirmishes in Poland between the people and troops; I was told that, even in Russia, there was a conspiracy against the czar and the whole royal family.

I am equally passionate about the struggle between the North and the Southern American states. Of course, my heart goes out to the North. But alas! It is the South who acted with the most force, wisdom, and solidarity, which makes them worthy of the triumph they have received in every encounter so far. It is true that the South has been preparing for war for three years now, while the North has been forced to improvise. The surprising success of the ventures of the American people, for the most part happy; the banality of the material well being, where the heart is absent; and the national vanity, altogether infantile and sustained with very little cost; all seem to have helped deprave these people, and perhaps this stubborn struggle will be beneficial to them in so much as it helps the nation regain its lost soul. This is my first impression; but it could very well be that I will change my mind upon seeing things up close. The only thing is, I will not have enough time to examine really closely.- Letter to Aleksandr Ivanovich Herzen and Ogareff from San Francisco (3 October 1861); published in Correspondance de Michel Bakounine (1896) edited by Michel Dragmanov

- What all other men are is of the greatest importance to me. However independent I may imagine myself to be, however far removed I may appear from mundane considerations by my social status, I am enslaved to the misery of the meanest member of society. The outcast is my daily menace. Whether I am Pope, Czar, Emperor, or even Prime Minister, I am always the creature of their circumstance, the conscious product of their ignorance, want and clamoring. They are in slavery, and I, the superior one, am enslaved in consequence.

- Solidarity in Liberty: The Workers' Path to Freedom (1867)

- In order to touch the heart and gain the confidence, the assent, the adhesion, and the co-operation of the illiterate legions of the proletariat — and the vast majority of proletarians unfortunately still belong in this category — it is necessary to begin to speak to those workers not of the general sufferings of the international proletariat as a whole but of their particular, daily, altogether private misfortunes. It is necessary to speak to them of their own trade and the conditions of their work in the specific locality where they live; of the harsh conditions and long hours of their daily work, of the small pay, the meanness of their employer, the high cost of living, and how impossible it is for them properly to support and bring up a family.

- Political Freedom without economic equality is a pretense, a fraud, a lie; and the workers want no lying.

- "The Red Association" (1870)

- If there is a devil in human history, that devil is the principle of command. It alone, sustained by the ignorance and stupidity of the masses, without which it could not exist, is the source of all the catastrophes, all the crimes, and all the infamies of history.

- "On the Program of the Alliance" (1871), in Bakunin on Anarchy (1971), translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff

- If there is a devil in history, it is the power principle.

- Appears in leader to film Human Resources: Social Engineering in the 20th century

- I am a fanatic lover of liberty, considering it as the unique condition under which intelligence, dignity and human happiness can develop and grow; not the purely formal liberty conceded, measured out and regulated by the State, an eternal lie which in reality represents nothing more than the privilege of some founded on the slavery of the rest; not the individualistic, egoistic, shabby, and fictitious liberty extolled by the School of J.-J. Rousseau and other schools of bourgeois liberalism, which considers the would-be rights of all men, represented by the State which limits the rights of each — an idea that leads inevitably to the reduction of the rights of each to zero. No, I mean the only kind of liberty that is worthy of the name, liberty that consists in the full development of all the material, intellectual and moral powers that are latent in each person; liberty that recognizes no restrictions other than those determined by the laws of our own individual nature, which cannot properly be regarded as restrictions since these laws are not imposed by any outside legislator beside or above us, but are immanent and inherent, forming the very basis of our material, intellectual and moral being — they do not limit us but are the real and immediate conditions of our freedom.

- To revolt is a natural tendency of life. Even a worm turns against the foot that crushes it. In general, the vitality and relative dignity of an animal can be measured by the intensity of its instinct to revolt.

- It is the peculiarity of privilege and of every privileged position to kill the intellect and heart of man. The privileged man, whether he be privileged politically or economically, is a man depraved in intellect and heart.

- As quoted in "Socialism" article of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th edition (1887), edited by Thomas Spencer Baynes with assistance of William Robertson Smith, Vol. 22, p. 216, Charles Scribner's Sons

- We wish, in a word, equality — equality in fact as a corollary, or rather, as primordial condition of liberty. From each according to his faculties, to each according to his needs; that is what we wish sincerely and energetically.

- As quoted in The Old Order and the New (1890) by J. Morris Davidson

- No theory, no ready-made system, no book that has ever been written will save the world. I cleave to no system. I am a true seeker.

- As quoted in Michael Bakunin (1937) by E.H. Carr, p. 175

- I hate Communism because it is the negation of liberty and because humanity is for me unthinkable without liberty. I am not a Communist, because Communism concentrates and swallows up in itself for the benefit of the State all the forces of society, because it inevitably leads to the concentration of property in the hands of the State, whereas I want the abolition of the State, the final eradication of the principle of authority and the patronage proper to the State, which under the pretext of moralizing and civilizing men has hitherto only enslaved, persecuted, exploited and corrupted them. I want to see society and collective or social property organized from below upwards, by way of free association, not from above downwards, by means of any kind of authority whatsoever.

- As quoted in Michael Bakunin (1937) by E.H. Carr, p. 356

- All exercise of authority perverts, and submission to authority humiliates.

- As quoted in Michael Bakunin (1937), E.H. Carr, p. 453

- Every state, like every theology, assumes man to be fundamentally bad and wicked.

- As quoted in Michael Bakunin (1937), E.H. Carr, p. 453

- Even the most wretched individual of our present society could not exist and develop without the cumulative social efforts of countless generations. Thus the individual, his freedom and reason, are the products of society, and not vice versa: society is not the product of individuals comprising it; and the higher, the more fully the individual is developed, the greater his freedom — and the more he is the product of society, the more does he receive from society and the greater his debt to it.

- As quoted in The Philosophy of Bakunin (1953) edited by G. P. Maximoff, p. 158

- Freedom is the absolute right of every human being to seek no other sanction for his actions but his own conscience, to determine these actions solely by his own will, and consequently to owe his first responsibility to himself alone.

- As quoted in Anarchism: From Theory to Practice, Daniel Guérin, New York: NY, Monthly Review Press (1970) p. 31

- By striving to do the impossible, man has always achieved what is possible. Those who have cautiously done no more than they believed possible have never taken a single step forward.

- As quoted in The Explorers (1996) by Paolo Novaresio ISBN 1-55670-495-X

Reasoned Proposal to the Central Committee of the League for Peace and Freedom (1867)

[edit]- "Reasoned Proposal to the Central Committee of the League of Peace and Freedom", at the League's first congress held in Geneva (September 1867); also known as "Federalism, Socialism, Anti-Theologism" (Fédéralisme, socialisme et antithéologisme)

- There is but one way to bring about the triumph of liberty, of justice, and of peace in Europe's international relations, to make civil war impossible between the different peoples who make up the European family; and that is the formation of the United States of Europe.

- Unity is the great goal toward which humanity moves irresistibly. But it becomes fatal, destructive of the intelligence, the dignity, the well-being of individuals and peoples whenever it is formed without regard to liberty, either by violent means or under the authority of any theological, metaphysical, political, or even economic idea. That patriotism which tends toward unity without regard to liberty is an evil patriotism, always disastrous to the popular and real interests of the country it claims to exalt and serve. Often, without wishing to be so, it is a friend of reaction – an enemy of the revolution, i.e., the emancipation of nations and men.

- Liberty is so great a magician, endowed with so marvelous a power of productivity, that under the inspiration of this spirit alone, North America was able within less than a century to equal, and even surpass, the civilization of Europe.

- When we speak of justice we do not thereby mean the justice which is imparted to us in legal codes and by Roman law, founded for the most part on acts of force and violence consecrated by time and by the blessings of some church, Christian or pagan and, as such, accepted as an absolute, the rest being nothing but the logical consequence of the same. I speak of that justice which is based solely upon human conscience, the justice which you will rediscover deep in the conscience of every man, even in the conscience of the child, and which translates itself into simple equality.

This justice, which is so universal but which nevertheless, owing to the encroachments of force and to the influence of religion, has never as yet prevailed in the world of politics, of law, or of economics, should serve as a basis for the new world. Without it there is no liberty, no republic, no prosperity, no peace! It should therefore preside at all our resolutions in order that we may effectively cooperate in establishing peace.

- As we are convinced that the real attainment of liberty, of justice, and of peace in the world will be impossible so long as the immense majority of the populations are dispossessed of property, deprived of education and condemned to political and social nonbeing and a de facto if not a de jure slavery, through their state of misery as well as their need to labor without rest or leisure, in producing all the wealth in which the world is glorying today, and receiving in return but a small portion hardly sufficient for their daily bread;

As we are convinced that for all these populations, hitherto so terribly maltreated through the centuries, the question of bread is the question of intellectual emancipation, of liberty, and of humanity;

As we are convinced that liberty without socialism is privilege, injustice; and that socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality;

Now therefore, the League highly proclaims the need for a radical social and economic reform, whose aim shall be the deliverance of the people's labor from the yoke of capital and property, upon a foundation of the strictest justice — not juridical, not theological, not metaphysical, but simply human justice, of positive science and the most absolute liberty.- Variant translation: We are convinced that freedom without Socialism is privilege and injustice, and that Socialism without freedom is slavery and brutality.

- As quoted in The Political Philosophy of Bakunin: Scientific Anarchism (1953) edited by Grigoriĭ Petrovich Maksimov, p. 269

- Variant translation: We are convinced that freedom without Socialism is privilege and injustice, and that Socialism without freedom is slavery and brutality.

Second Address to the Second Congress of Peace and Freedom (1868)

[edit]- Second Address to the Second Congress of Peace and Freedom (23 September 1868)

- Do not believe, Gentlemen, that I recoil before the frank explanation of my socialist ideas. I could ask nothing better than to defend them here. But I do not think that the regulatory fifteen minutes would suffice for this debate. However there is one point, one accusation hurled against me that I cannot leave without a response.

Because I demand the economic and social equalization of classes and individuals, because with the Congress of laborers at Brussels, I have declared myself a partisan of collective property, I have been reproached for being a communist. What difference, they have said to me, do you intend between communism and collectivity? I am astonished, truly, that Mr. Chaudey does not understand that difference, he, the testamentary executor of Proudhon! I detest communism, because it is the negation of liberty and because I can conceive nothing human without liberty. I am not a communist because communism concentrates and causes all the power of society to be concentrated in the State, because it leads necessarily to the centralization of property in the hands of the State, while I want the abolition of the State, — the radical extirpation of that principle of authority and of the guardianship of the State, which under the pretext of moralizing and civilizing men, have thus far enslaved, oppressed, exploited and depraved them, I want the organization of society and of collective or social property from bottom to top, by the way of free association, and not from top to bottom by means of any sort of authority. Wishing the abolition of the State, I want the abolition of individually hereditary property, which is only an institution of the State, nothing but a consequence of the very principle of the State. That is the sense in which, Gentlemen, I am collectivist and not at all communist.

- Equality, proclaimed in 1793, has been one of the greatest conquests of the French Revolution. Despite all the reactions which have arrived since, that great principle has triumphed in the political economy of Europe. In the most advanced countries, it is called the equality of politic rights; in the other countries, civil equality — equality before the law. No country in Europe would dare to openly proclaim today the principle of political inequality.

But the history of the revolution itself and that of the seventy-five years that have passed since, we prove that political equality without economic equality is a lie. You would proclaim in vain the equality of political rights, as long as society remains split by its economic organization into socially different layers — that equality will be nothing but a fiction.

- Here then is what we understand by these words: “the equalization of the classes.” It would perhaps have been better to say suppression of the classes, the unification of society by the abolition of economic and social inequality. But we have also demanded the equalization of the individuals, and it is there especially that we attract all the thunderbolts of outraged eloquence from our adversaries. One has made use of that part of our proposition to prove in a conclusive manner that we are nothing but communists.

- Allow me, Gentlemen, to pose this question in a more serious manner. Do I need to tell you that it is not a question at first of the natural, physiological, ethnographic difference that exists between individuals, but of the social difference, that is produced by the economic organization of society? Give to all the children, from their birth, the same means of maintenance, education, and instruction; give then to all the men thus raised the same social milieu, the same means of earning their living by their own labor, and you will see then that many of these differences, that we believe to be natural differences, will disappear because they are nothing but the effect of an unequal division of the conditions of intellectual and physical development — of the conditions of life.

Program and Object of the Secret Revolutionary Organisation of the International Brotherhood (1868)

[edit]- Not official revolutionary commissars in any sort of sashes, but rather revolutionary propagandists are to be dispatched into all the provinces and communes and particularly among the peasants who cannot be revolutionised by principles, nor by the decrees of any dictatorship, but only by the act of revolution itself, that is to say, by the consequences that will inevitably ensure in every commune from complete cessation of the legal and official existence of the state.

- The peoples' revolution .... will arrange its revolutionary organisation from the bottom up and from the periphery to the centre, in keeping with the principle of liberty.

Man, Society, and Freedom (1871)

[edit]

- As translated by Sam Dolgoff in Bakunin on Anarchy (1971)

- The materialistic, realistic, and collectivist conception of freedom, as opposed to the idealistic, is this: Man becomes conscious of himself and his humanity only in society and only by the collective action of the whole society. He frees himself from the yoke of external nature only by collective and social labor, which alone can transform the earth into an abode favorable to the development of humanity. Without such material emancipation the intellectual and moral emancipation of the individual is impossible. He can emancipate himself from the yoke of his own nature, i.e. subordinate his instincts and the movements of his body to the conscious direction of his mind, the development of which is fostered only by education and training. But education and training are preeminently and exclusively social … hence the isolated individual cannot possibly become conscious of his freedom.

To be free … means to be acknowledged and treated as such by all his fellowmen. The liberty of every individual is only the reflection of his own humanity, or his human right through the conscience of all free men, his brothers and his equals.

I can feel free only in the presence of and in relationship with other men. In the presence of an inferior species of animal I am neither free nor a man, because this animal is incapable of conceiving and consequently recognizing my humanity. I am not myself free or human until or unless I recognize the freedom and humanity of all my fellowmen.

Only in respecting their human character do I respect my own. ...

I am truly free only when all human beings, men and women, are equally free. The freedom of other men, far from negating or limiting my freedom, is, on the contrary, its necessary premise and confirmation.- Variant translations:

- A natural society, in the midst of which every man is born and outside of which he could never become a rational and free being, becomes humanized only in the measure that all men comprising it become, individually and collectively, free to an ever greater extent.

Note 1. To be personally free means for every man living in a social milieu not to surrender his thought or will to any authority but his own reason and his own understanding of justice; in a word, not to recognize any other truth but the one which he himself has arrived at, and not to submit to any other law but the one accepted by his own conscience. Such is the indispensable condition for the observance of human dignity, the incontestable right of man, the sign of his humanity.

To be free collectively means to live among free people and to be free by virtue of their freedom. As we have already pointed out, man cannot become a rational being, possessing a rational will, (and consequently he could not achieve individual freedom) apart from society and without its aid. Thus the freedom of everyone is the result of universal solidarity. But if we recognize this solidarity as the basis and condition of every individual freedom, it becomes evident that a man living among slaves, even in the capacity of their master, will necessarily become the slave of that state of slavery, and that only by emancipating himself from such slavery will he become free himself.

Thus, too, the freedom of all is essential to my freedom. And it follows that it would be fallacious to maintain that the freedom of all constitutes a limit for and a limitation upon my freedom, for that would be tantamount to the denial of such freedom. On the contrary, universal freedom represents the necessary affirmation and boundless expansion of individual freedom.- This passage was translated as Part III : The System of Anarchism , Ch. 13: Summation, Section VI, in The Political Philosophy of Bakunin : Scientific Anarchism (1953), compiled and edited by G. P. Maximoff

- Man does not become man, nor does he achieve awareness or realization of his humanity, other than in society and in the collective movement of the whole society; he only shakes off the yoke of internal nature through collective or social labor... and without his material emancipation there can be no intellectual or moral emancipation for anyone... man in isolation can have no awareness of his liberty. Being free for man means being acknowledged, considered and treated as such by another man, and by all the men around him. Liberty is therefore a feature not of isolation but of interaction, not of exclusion but rather of connection... I myself am human and free only to the extent that I acknowledge the humanity and liberty of all my fellows... I am properly free when all the men and women about me are equally free. Far from being a limitation or a denial of my liberty, the liberty of another is its necessary condition and confirmation.

- My dignity as a man, my human right which consists of refusing to obey any other man, and to determine my own acts in conformity with my convictions is reflected by the equally free conscience of all and confirmed by the consent of all humanity. My personal freedom, confirmed by the liberty of all, extends to infinity.

The materialistic conception of freedom is therefore a very positive, very complex thing, and above all, eminently social, because it can be realized only in society and by the strictest equality and solidarity among all men.

- The first revolt is against the supreme tyranny of theology, of the phantom of God. As long as we have a master in heaven, we will be slaves on earth.

- We must make a very precise distinction between the official and consequently dictatorial prerogatives of society organized as a state, and of the natural influence and action of the members of a non-official, non-artificial society.

Rousseau's Theory of the State (1873)

[edit]

- We … have humanity divided into an indefinite number of foreign states, all hostile and threatened by each other. There is no common right, no social contract of any kind between them; otherwise they would cease to be independent states and become the federated members of one great state. But unless this great state were to embrace all of humanity, it would be confronted with other great states, each federated within, each maintaining the same posture of inevitable hostility. War would still remain the supreme law, an unavoidable condition of human survival.

Every state, federated or not, would therefore seek to become the most powerful. It must devour lest it be devoured, conquer lest it be conquered, enslave lest it be enslaved, since two powers, similar and yet alien to each other, could not coexist without mutual destruction.

The State, therefore, is the most flagrant, the most cynical, and the most complete negation of humanity. It shatters the universal solidarity of all men on the earth, and brings some of them into association only for the purpose of destroying, conquering, and enslaving all the rest. It protects its own citizens only; it recognises human rights, humanity, civilisation within its own confines alone. Since it recognises no rights outside itself, it logically arrogates to itself the right to exercise the most ferocious inhumanity toward all foreign populations, which it can plunder, exterminate, or enslave at will. If it does show itself generous and humane toward them, it is never through a sense of duty, for it has no duties except to itself in the first place, and then to those of its members who have freely formed it, who freely continue to constitute it or even, as always happens in the long run, those who have become its subjects. As there is no international law in existence, and as it could never exist in a meaningful and realistic way without undermining to its foundations the very principle of the absolute sovereignty of the State, the State can have no duties toward foreign populations. Hence, if it treats a conquered people in a humane fashion, if it plunders or exterminates it halfway only, if it does not reduce it to the lowest degree of slavery, this may be a political act inspired by prudence, or even by pure magnanimity, but it is never done from a sense of duty, for the State has an absolute right to dispose of a conquered people at will.

This flagrant negation of humanity which constitutes the very essence of the State is, from the standpoint of the State, its supreme duty and its greatest virtue. It bears the name patriotism, and it constitutes the entire transcendent morality of the State. We call it transcendent morality because it usually goes beyond the level of human morality and justice, either of the community or of the private individual, and by that same token often finds itself in contradiction with these. Thus, to offend, to oppress, to despoil, to plunder, to assassinate or enslave one's fellowman is ordinarily regarded as a crime. In public life, on the other hand, from the standpoint of patriotism, when these things are done for the greater glory of the State, for the preservation or the extension of its power, it is all transformed into duty and virtue. And this virtue, this duty, are obligatory for each patriotic citizen; everyone is supposed to exercise them not against foreigners only but against one's own fellow citizens, members or subjects of the State like himself, whenever the welfare of the State demands it.

This explains why, since the birth of the State, the world of politics has always been and continues to be the stage for unlimited rascality and brigandage, brigandage and rascality which, by the way, are held in high esteem, since they are sanctified by patriotism, by the transcendent morality and the supreme interest of the State. This explains why the entire history of ancient and modern states is merely a series of revolting crimes; why kings and ministers, past and present, of all times and all countries — statesmen, diplomats, bureaucrats, and warriors — if judged from the standpoint of simple morality and human justice, have a hundred, a thousand times over earned their sentence to hard labour or to the gallows. There is no horror, no cruelty, sacrilege, or perjury, no imposture, no infamous transaction, no cynical robbery, no bold plunder or shabby betrayal that has not been or is not daily being perpetrated by the representatives of the states, under no other pretext than those elastic words, so convenient and yet so terrible: "for reasons of state."

- We are firmly convinced that the most imperfect republic is a thousand times better than the most enlightened monarchy. In a republic, there are at least brief periods when the people, while continually exploited, is not oppressed; in the monarchies, oppression is constant. The democratic regime also lifts the masses up gradually to participation in public life--something the monarchy never does. Nevertheless, while we prefer the republic, we must recognise and proclaim that whatever the form of government may be, so long as human society continues to be divided into different classes as a result of the hereditary inequality of occupations, of wealth, of education, and of rights, there will always be a class-restricted government and the inevitable exploitation of the majorities by the minorities.

The State is nothing but this domination and this exploitation, well regulated and systematised.

God and the State (1871; publ. 1882)

[edit]

- The liberty of man consists solely in this: that he obeys natural laws because he has himself recognized them as such, and not because they have been externally imposed upon him by any extrinsic will whatever, divine or human, collective or individual.

- Does it follow that I reject all authority? Far from me such a thought. In the matter of boots, I refer to the authority of the bootmaker; concerning houses, canals, or railroads, I consult that of the architect or engineer. For such or such special knowledge I apply to such or such a savant. But I allow neither the bootmaker nor the architect nor the savant to impose his authority upon me. I listen to them freely and with all the respect merited by their intelligence, their character, their knowledge, reserving always my incontestable right of criticism and censure. I do not content myself with consulting authority in any special branch; I consult several; I compare their opinions, and choose that which seems to me the soundest. But I recognize no infallible authority, even in special questions; consequently, whatever respect I may have for the honesty and the sincerity of such or such an individual, I have no absolute faith in any person. Such a faith would be fatal to my reason, to my liberty, and even to the success of my undertakings; it would immediately transform me into a stupid slave, an instrument of the will and interests of others.

- I bow before the authority of special men because it is imposed upon me by my own reason. I am conscious of my inability to grasp, in all its details and positive developments, any very large portion of human knowledge. The greatest intelligence would not be equal to a comprehension of the whole. Thence results, for science as well as for industry, the necessity of the division and association of labor. I receive and I give — such is human life. Each directs and is directed in his turn. Therefore there is no fixed and constant authority, but a continual exchange of mutual, temporary, and, above all, voluntary authority and subordination.

- This contradiction lies here: they wish God, and they wish humanity. They persist in connecting two terms which, once separated, can come together again only to destroy each other. They say in a single breath: "God and the liberty of man," "God and the dignity, justice, equality, fraternity, prosperity of men" — regardless of the fatal logic by virtue of which, if God exists, all these things are condemned to non-existence. For, if God is, he is necessarily the eternal, supreme, absolute master, and, if such a master exists, man is a slave; now, if he is a slave, neither justice, nor equality, nor fraternity, nor prosperity are possible for him. In vain, flying in the face of good sense and all the teachings of history, do they represent their God as animated by the tenderest love of human liberty: a master, whoever he may be and however liberal he may desire to show himself, remains none the less always a master. His existence necessarily implies the slavery of all that is beneath him. Therefore, if God existed, only in one way could he serve human liberty — by ceasing to exist.

- Amoureux et jaloux de la liberté humaine, et la considérant comme la condition absolue de tout ce que nous adorons et respectons dans l'humanité, je retourne la phrase de Voltaire, et je dis : Si Dieu existait réellement, il faudrait le faire disparaître.

- A jealous lover of human liberty, deeming it the absolute condition of all that we admire and respect in humanity, I reverse the phrase of Voltaire, and say that, if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him.

- Ch. II; Variants or variant translations of this statement have also been attributed to Bakunin:

The first revolt is against the supreme tyranny of theology, of the phantom of God. As long as we have a master in heaven, we will be slaves on earth.

A boss in Heaven is the best excuse for a boss on earth, therefore If God did exist, he would have to be abolished.

- Of escape there are but three methods — two chimerical and a third real. The first two are the dram-shop and the church, debauchery of the body or debauchery of the mind; the third is social revolution.

- Nothing, in fact, is as universal or as ancient as the iniquitous and absurd; truth and justice, on the contrary, are the least universal, the youngest features in the development of human society.

- All religions, with their gods, their demigods, and their prophets, their messiahs and their saints, were created by the credulous fancy of men who had not attained the full development and full possession of their faculties. Consequently, the religious heaven is nothing but a mirage in which man, exalted by ignorance and faith, discovers his own image, but enlarged and reversed — that is, divinized. The history of religion, of the birth, grandeur, and decline of the gods who have succeeded one another in human belief, is nothing, therefore, but the development of the collective intelligence and conscience of mankind.

- All religions are cruel, all founded on blood; for all rest principally on the idea of sacrifice — that is, on the perpetual immolation of humanity to the insatiable vengeance of divinity.

- In a word, we reject all legislation, all authority, and all privileged, licensed, official, and legal influence, even though arising from universal suffrage, convinced that it can turn only to the advantage of a dominant minority of exploiters against the interest of the immense majority in subjection to them. This is the sense in which we are really Anarchists.

- The great honor of Christianity, its incontestable merit, and the whole secret of its unprecedented and yet thoroughly legitimate triumph, lay in the fact that it appealed to that suffering and immense public to which the ancient world, a strict and cruel intellectual and political aristocracy, denied even the simplest rights of humanity. Otherwise it never could have spread.

- Dover edition, p. 75

Statism and Anarchy (1873)

[edit]

- If there is a state, then necessarily there is domination and consequently slavery. A state without slavery, open or camouflaged, is inconceivable — that is why we are enemies of the state.

- There can be no revolution without widespread and passionate destruction, a destruction salutary and fruitful precisely because out of it, and by means of it alone, new worlds are born and arise.

- The modern state, in its essence and objectives, is necessarily a military state, and a military state necessarily becomes an aggressive state. If it does not conquer others it will itself be conquered, for the simple reason that wherever force exists, it absolutely must be displayed or put into action. From this again it follows that the modern state must without fail be huge and powerful; that is the indispensable condition for its preservation.

- At the present time a serious, strong state can have but one sound foundation — military and bureaucratic centralization. Between a monarchy and the most democratic republic there is only one essential difference: in the former, the world of officialdom oppresses and robs the people for the greater profit of the privileged and propertied classes, as well as to line its own pockets, in the name of the monarch; in the latter, it oppresses and robs the people in exactly the same way, for the benefit of the same classes and the same pockets, but in the name of the people’s will. In a republic a fictitious people, the "legal nation" supposedly represented by the state, smothers the real, live people. But it will scarcely be any easier on the people if the cudgel with which they are beaten is called the people's cudgel.

- This means that no state, howsoever democratic its forms, not even the reddest political republic — a people's republic only in the sense of the lie known as popular representation — is capable of giving the people what they need: the free organization of their own interests from below upward, without any interference, tutelage, or coercion from above. That is because no state, not even the most republican and democratic, not even the pseudo-popular state contemplated by Marx, in essence represents anything but government of the masses from above downward, by an educated and thereby privileged minority which supposedly understands the real interests of the people better than the people themselves.

- The people should never be deceived, under any pretext or for any purpose. It would not only be criminal but detrimental to the revolutionary cause, for deception of any kind, by its very nature, is shortsighted, petty, narrow, always sewn with rotten threads, so that it inevitably tears and is exposed.

- "Appendix A"

- A person is strong only when he stands upon his own truth, when he speaks and acts from his deepest convictions. Then, whatever the situation he may be in, he always knows what he must say and do. He may fall, but he cannot bring shame upon himself or his cause. If we seek the liberation of the people by means of a lie, we will surely grow confused, go astray, and lose sight of our objective, and if we have any influence at all on the people we will lead them astray as well — in other words, we will be acting in the spirit of reaction and to its benefit.

- "Appendix A"

- As one of our Swiss friends put it: "Now every German tailor living in Japan, China, or Moscow feels that he has the German navy and all of Germany's power behind him. This proud consciousness sends him into an insane rapture: the German has finally lived to see the day when he can say with pride, relying on his own state, like an Englishman or an American, 'I am a German.' True, when the Englishman or American says 'I am an Englishman,' or 'I am an American,' he is saying 'I am a free man.' The German, however, is saying 'I am a slave, but my emperor is stronger than all other princes, and the German soldier who is strangling me will strangle all of you.'"

Disputed

[edit]- Marx is a Jew and is surrounded by a crowd of little, more or less intelligent, scheming, agile, speculating Jews, just as Jews are everywhere, commercial and banking agents, writers, politicians, correspondents for newspapers of all shades; in short, literary brokers, just as they are financial brokers, with one foot in the bank and the other in the socialist movement, and their arses sitting upon the German press. They have grabbed hold of all newspapers, and you can imagine what a nauseating literature is the outcome of it. Now this entire Jewish world, which constitutes an exploiting sect, a people of leeches, a voracious parasite, Marx feels an instinctive inclination and a great respect for the Rothschilds. This may seem strange. What could there be in common between communism and high finance? Ho ho! The communism of Marx seeks a strong state centralization, and where this exists there must inevitably exist a state central bank, and where this exists, there the parasitic Jewish nation, which speculates upon the labor of the people, will always find the means for its existence.

- Letters to the internationals of Bologna - Explanatory and supporting documents (Lettres aux internationaux de Bologne - Pièces explicatives et justificatives), December 1871. Heavily paraphrased from the original into English by Max Nomad in Jew Baiting On The Left, published in the Poale Zion's journal Jewish Frontier, p. 8, 1940, Volume 7, edited by Hayim Greenberg and Marie Syrkin. The journal was soon quoted by Elizabeth Dilling, under the pseudonym "Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson", in The Octopus. Sons of Liberty. 1940. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-89562-094-1.

Quotes about Bakunin

[edit]

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

- As a romantic rebel and an active force in history, Bakunin exerted a personal attraction that Marx could never rival. … His broad magnanimity and childlike enthusiasm, his burning passion for liberty and equality, his volcanic onslaughts against privilege and injustice — all gave him enormous appeal in the libertarian circles of his day.

But Bakunin, as his critics never tired of pointing out, was not a systematic thinker. Nor did he ever claim to be. … He refused to recognize the existence of any preconceived or preordained laws of history. … He believed, on the contrary, that men shaped their own destinies, that their lives cannot be squeezed into a Procrustean bed of abstract social formulas. … And yet, however erratic and unmethodical, his writings abound in flashes of insight that illuminate some of the most important social questions of his time — and of ours.- Paul Avrich, Introduction to God and the State (1970 Dover edition)

- I looked up to these Russians who could discuss by the hour the theories of Marx and Bakunin, who had participated in demonstrations and other revolutionary activity.

- Angelica Balabanoff My Life As a Rebel (1938)

- To classify the views with those of Bakunin as forms of semi-anarchistic 'populism', or with those of Proudhon or Rodbertus or Chernyshevsky as yet another variant of early socialism with an agrarian bias, is to leave out his most arresting contribution to political theory. This injustice deserves to be remedied.

- Isaiah Berlin, Russian Thinkers (1978)

- Bakunin is a many-sided phenomenon and could be studied in many aspects and from many points of view. He is-rightly, on the whole-regarded as the father of anarchism; for William Godwin, to whom the title is sometimes awarded, never left the plane of abstract theory, and the anarchism of Proudhon took on the special concrete mould of syndicalism and exercised a lasting influence on French politics and French thought mainly in that guise. Bakunin was the apostle of liberty in its absolute form-a liberty which, as M. Hepner remarks, had nothing in common with Hegel's conception of liberty realizing itself in the State. Yet Bakunin, on the strength of his emphasis on propaganda by deed and of his willingness to appeal to the "evil passions", has often been convicted of an affinity with the movements which ultimately issued in Fascism. He was always ready to subordinate theory to the spontaneous character of the revolutionary impulse; in this respect he was a revolutionary empiricist and stood at the opposite pole to Marx. When Lenin in 1917 announced that, in spite of the rudimentary progress made by the Russian bourgeois revolution, the socialist revolution was at hand, the Mensheviks-and some of his own followers-branded him as a disciple of Bakunin and not of Marx.

- E. H. Carr, "The Pan-Slav Tradition" (1951)

- On the first day of a revolution, he is a perfect treasure; on the second, he ought to be shot.

- Marc Caussidière, Préfecture de Police, in early 1848, as quoted in Michael Bakunin (1961) by E.H. Carr, p. 150.

- Bakunin's social theory began, and almost ended, with liberty. Against the claims of liberty nothing else in his view was worth consideration at all. He attacked, remorselessly and without qualification, every institution that seemed to him to be inconsistent with liberty.

- G. D. H. Cole, as quoted in Bakunin : The Philosophy of Freedom (1993) by Brian Morris, p. 92

- The world carnage put an end to the golden era when a Bakunin and a Herzen, a Marx and a Kropotkin, a Malatesta and a Lenin, Vera Sazulich, Louise Michel, and all the others could come and go without hindrance. In those days who cared about passports or visas? Who worried about one particular spot on earth? The whole world was one's country.

- Emma Goldman "The Tragedy of the Political Exiles" (1934) in The Nation

- Although Bakunin had included in the programme of his International Alliance of Social Democracy the explicit aim of abolishing sexual inequality along with class inequality, the anarchist record on women's rights was an uneven one.

- Maxine Molyneux Women's Movements in International Perspective: Latin America and Beyond (2000)

- This man was born not under an ordinary star but under a comet.

- Alexander Herzen, as quoted in The Doctrine of Anarchism of Michael A. Bakunin (1968) by Eugène Pyziur, p. 1

- Everything about him was colossal, and he was full of exuberance and strength.

- Richard Wagner, as quoted in the Introduction to God and the State (1979 Dover edition)

See also

[edit]