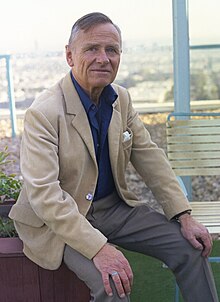

Christopher Isherwood

Appearance

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was a British-American writer.

Quotes

[edit]- It should be noted that throughout Isherwood's published memoirs he regularly refers to himself with a third person perspective.

- I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.

- "Berlin Diary" (1930) from Goodbye to Berlin (1939)

- If I fear anything, I fear the atmosphere of the war, the power which it gives to all the things I hate — the newspapers, the politicians, the puritans, the scoutmasters, the middle-aged merciless spinsters. I fear the way I might behave, if I were exposed to this atmosphere. I shrink from the duty of opposition. I am afraid I should be reduced to a chattering enraged monkey, screaming back hate at their hate.

- Diary entry, 20 January 1940, from The Diaries of Christopher Isherwood, vol I: 1939 - 1960, edited by Katherine Bucknell, p. 84

- It seems to me that the real clue to your sex orientation lies in your romantic feelings rather than in your sexual feelings. If you are really gay, you are able to fall in love with a man, not just enjoy having sex with him.

- As quoted in "Christopher Isherwood Interview" with Winston Leyland (1973), from Conversations with Christopher Isherwood, ed. James J. Berg and Chris Freeman (2001) ISBN 1-57806-408-2, p. 106

- At one campus where I was lecturing, I asked a friend, "How many of my colleagues know I'm gay?" He answered, "All of them." I wasn't surprised. But, just the same, it was kind of spooky, because not one of them had ever given me the faintest sign that he or she knew. If I had spoken about it myself, most of them would have felt it was in bad taste.

- As quoted in "Christopher Isherwood Interview" with Winston Leyland (1973), from Conversations with Christopher Isherwood, ed. James J. Berg and Chris Freeman (2001), p. 108

- The images which remained in the memory are not in themselves terrible or rigorous: they are of boot-lockers, wooden desks, lists on boards, name-tags in clothes — yes, the name pre-eminently; the name which in a sense makes you nameless, less individual rather than more so: Bradshaw-Isherwood, C.W. in its place on some alphabetical list; the cold daily, hourly reminder that you are not the unique, the loved, the household’s darling, but just one among many. I suppose that this loss of identity is really much of the painfulness which lies at the bottom of what is called Homesickness; it is not Home that one cries for but one’s home-self.

- As quoted in Isherwood : A Life (2004) by Peter Parker, pp. 40-41; this reminiscence is from the first draft of the biographical study Isherwood did of his parents (Huntington CI 1082: 81). The version published in Kathleen and Frank (1971), chapter 15, p. 285 differs slightly.

- I believe the Gita to be one of the major religious documents of the world. If its teachings did not seem to me to agree with those of the other gospels and scriptures, then my own system of values would be thrown into confusion, and I should feel completely bewildered. The Gita is not simply a sermon, but a philosophical treatise.

- (source: Living Wisdom: Vedanta in the West - Pravrajika Vrajaprana (Editor) Essay on Gita and the War - By Christopher Isherwood 93-99).

Prater Violet (1945)

[edit]- 'The whole beauty of the Film is that it has a certain fixed speed. The way you see it is mechanically conditioned. I mean, take a painting - you can just glance at it, or you can stare at the left hand top corner for half an hour. Same thing with a book. The author can't stop you from skimming it, or staring at the last chapter and reading backwards. The point is, you choose your approach. When you go into a cinema it's different. There's the film, and you have to look at it as the director wants you to look at it. He makes his points, one after another, and he allows you a certain number of seconds or minutes to grasp each one. If you miss anything he won't repeat himself, and he won't stop to explain. He can't. He's started something and he has to go through with it.'

- at p.24-25 [page numbers per the Methuen London Ltd 1984 paperback edition.]

- 'Let me tell you something,' he began, as he dropped my manuscript casually into the waste-paper-basket. 'The Film is a symphony. Each movement is written in a certain key. There is a note which has to be chosen and struck immediately. It is characteristic of the whole. It commands the attention.'

He started to describe the opening sequence. It was astounding. Everything came to life. The trees began to tremble in the evening breeze, the music was heard, the roundabouts were set in motion. And the people talked. Bergmann improvised their conversation, partly in German, partly in ridiculous English; and it was vivid and real. It was all so simple, so effective, so obvious. Why hadn't I thought of it myself?- at p.27-28

- 'All these people,' Bergmann continued, 'will be dead. All of them. . . . No, there is one—' He pointed to a fat, inoffensive man sitting alone in a distant corner. 'He will survive. He is the kind that will do anything, anything to be allowed to live. He will invite the conquerors to his home, force his wife to cook for them and serve the dinner on his bended knees. He will denounce his mother. He will offer his sister to a common soldier. He will act as a spy in prisons. He will spit on the Sacrament. He will hold down his daughter while they rape her. And, as a reward for this, he will be given a job as boot-black in a public lavatory, and he will lick the dirt from people's shoes with his tongue...'

- at p.33

- The result of the rebuilding was a maze of crooked stairways, claustrophobic passages, abrupt dangerous ramps and Alice in Wonderland doors. Most of the smaller rooms were overcrowded, under-ventilated, separated only by plywood partitions and lit by naked bulbs hanging from wires. Everything was provisional, and liable to electrocute you, fall on your head, or come apart in your hand.

- at p.52

- 'Why should you do a job anyway? What's the incentive?'

'The incentive is to fight anarchy. That's all Man lives for. Reclaiming life from its natural muddle. Making patterns.'

'Patterns for what?'

'For the sake of patterns. To create meaning. What else is there?'

'And what about the things that won't fit into your patterns?'

'Discard them.'- at p.55

- 'You know, sometimes I wonder what all this is for. Why not just peacefully end it?'

'We all think that. But we don't do it.'

'Surely you're not fool enough to imagine there's anything afterwards?'

'Perhaps. No, I suppose not. I don't think it makes much difference.'- at p.73

- 'We don't think enough [about the lot] of the other fellow, and that's a fact.'

- at p.83

- There is one question which we seldom ask each other directly: it is too brutal. And yet it is the only question worth asking our fellow-travellers. What makes you go on living? Why don't you kill yourself? Why is all this bearable? What makes you bear it?

Could I answer that question about myself? No. Yes. Perhaps . . . I supposed, vaguely, that it was a kind of balance, a complex of tensions. You did whatever was next on the list. A meal to be eaten. Chapter eleven to be written. The telephone rings. You go off somewhere in a taxi. There is one's job. There are amusements. There are people. There are books. There are things to be bought in shops. There is always something new. There has to be. Otherwise, the balance would be upset, the tension would break.- at p.98-99

A Single Man (1964)

[edit]- “’Let's face it, minorities are people who probably look and act and think differently from us and have faults we don't have. We may dislike the way they look and act, and we may hate their faults. And it’s better if we admit to disliking and hating them, than if we try to smear over our feelings with pseudo-liberal sentimentality. If we’re frank about our feelings, we have a safety valve; and if we have a safety-valve, we’re actually less likely to start persecuting. . . . I know that theory is unfashionable nowadays. We all keep trying to believe that, if we ignore something long enough, it’ll just vanish––

‘Where was I? Oh yes. . . Well, now, suppose this minority does get persecuted – never mind why – political, economic, psychological reasons – there always is a reason, no matter how wrong it is – that’s my point. And, of course, persecution itself is always wrong; I’m sure we all agree there. But, the worst of it is, we now run into another liberal heresy. Because the persecuting majority is vile, says the liberal, therefore the persecuted minority must be stainlessly pure. Can’t you see what nonsense that is? What’s to prevent the bad from being persecuted by the worse? Did all the Christian victims in the arena have to be saints?’

‘And I’ll tell you something else. A minority has its own kind of aggression. It absolutely dares the majority to attack it. It hates the majority — not without a cause, I grant you. It even hates the other minorities – because all minorities are in competition: each one proclaims that its sufferings are the worst and its wrongs are the blackest. And the more they all hate, and the more they're all persecuted, the nastier they become! Do you think it makes people nasty to be loved? You know it doesn’t! Then why should it make them nice to be loathed?’”- pps. 53-54

Exhumations (1966)

[edit]- California is a tragic country — like Palestine, like every Promised Land. Its short history is a fever-chart of migrations — the land rush, the gold rush, the oil rush, the movie rush, the Okie fruit-picking rush, the wartime rush to the aircraft factories — followed, in each instance, by counter-migrations of the disappointed and unsuccessful, moving sorrowfully homeward.

- "Los Angeles", p. 159

- The paternalist is a sentimentalist at heart, and the sentimentalist is always potentially cruel.

- "Los Angeles", p. 160

- To live sanely in Los Angeles (or, I suppose, in any other large American city) you have to cultivate the art of staying awake. You must learn to resist (firmly but not tensely) the unceasing hypnotic suggestions of the radio, the billboards, the movies and the newspapers; those demon voices which are forever whispering in your ear what you should desire, what you should fear, what you should wear and eat and drink and enjoy, what you should think and do and be. They have planned a life for you – from the cradle to the grave and beyond – which it would be easy, fatally easy, to accept. The least wandering of the attention, the least relaxation of your awareness, and already the eyelids begin to droop, the eyes grow vacant, the body starts to move in obedience to the hypnotist’s command. Wake up, wake up – before you sign that seven-year contract, buy that house you don’t really want, marry that girl you secretly despise. Don’t reach for the whisky, that won’t help you. You’ve got to think, to discriminate, to exercise your own free will and judgment. And you must do this, I repeat, without tension, quite rationally and calmly. For if you give way to fury against the hypnotists, if you smash the radio and tear the newspapers to shreds, you will only rush to the other extreme and fossilize into defiant eccentricity.

- "Los Angeles", p. 161

- An afternoon drive from Los Angeles will take you up into the high mountains, where eagles circle above the forests and the cold blue lakes, or out over the Mojave Desert, with its weird vegetation and immense vistas. Not very far away are Death Valley, and Yosemite, and Sequoia Forest with its giant trees which were growing long before the Parthenon was built; they are the oldest living things in the world. One should visit such places often, and be conscious, in the midst of the city, of their surrounding presence. For this is the real nature of California and the secret of its fascination; this untamed, undomesticated, aloof, prehistoric landscape which relentlessly reminds the traveller of his human condition and the circumstances of his tenure upon the earth. "You are perfectly welcome," it tells him, "during your short visit. Everything is at your disposal. Only, I must warn you, if things go wrong, don't blame me. I accept no responsibility. I am not part of your neurosis. Don't cry to me for safety. There is no home here. There is no security in your mansions or your fortresses, your family vaults or your banks or your double beds. Understand this fact, and you will be free. Accept it, and you will be happy."

- "Los Angeles" p. 162

The Paris Review interview (1973)

[edit]- Interview with W.I. Scobie in "Christopher Isherwood, The Art of Fiction No. 49" in The Paris Review(Spring 1974), also in Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, 4th series, ISBN 0140045430, p. 226

- I often feel that worse than the most fiendish Nazis were those Germans who went along with the persecution of the Jews not because they really disliked them but because it was the thing.

- I'll bet Shakespeare compromised himself a lot; anybody who's in the entertainment industry does to some extent.

- I'm horrified to find, as I look at these diaries of twenty-five years ago or more, that I don't remember who the people were. "Bill and Tony were constantly in and out. We went to La Jolla" — or something. I haven't the bluest idea who they were!

- I feel it's so easy to condemn this country [the United States]; but they don't understand that this is where the mistakes are being made — and made first, so that we're going to get the answers first.

Christopher and His Kind (1976)

[edit]

- Throughout this memoir, Isherwood refers to himself in the third person. · ISBN 0-8166-3863-2

- The Nazis hated culture itself, because it is essentially international and therefore subversive of nationalism. What they called Nazi culture was a local, perverted, nationalistic cult, by which a few major artists and many minor ones were honored for their Germanness, not their talent.

- Ch. 4, p. 65

- The Memorial was published on February 17, 1932. . . . I remember how one reviewer remarked that he had at first thought the novel contained a disproportionally large number of homosexual characters but had decided, on further reflection, that there were a lot more homosexuals about, nowadays.

- Ch. 5

- Christopher, like many other writers, was shockingly ignorant of the objective world, except where it touched his own experience. When he had to hide his ignorance beneath a veneer, he simply consulted someone who could supply him with the information he needed.

- Ch. 11, p. 192

- According to Christopher’s diary:

- The more I think about myself, the more I’m persuaded that, as a person, I really don’t exist. That is one of the reasons why I can’t believe in any orthodox religion: I cannot believe in my own soul. No, I am a chemical compound, conditioned by environment and education. My "character" is simply a repertoire of acquired tricks, my conversation a repertoire of adaptations and echoes, my "feelings" are dictated by purely physical, external stimuli.

- Christopher did well to call himself woolly-minded. All he has actually stated here is that he can’t believe in his own individuality as something absolute and eternal; the word "soul" is introduced, quite improperly, as a synonym for "person."

- Ch. 15, p. 306

- As the result of his talks with Gerald and with Gerald’s friend and teacher, the Hindu monk Prabhavananda, Christopher would find himself able to believe — as a possibility, at least — that an eternal impersonal presence (call it "the soul" if you like) exists within all creatures and is other than the mutable non-eternal "person." He would then feel that all his earlier difficulties had been merely semantic; that he could have been converted to this belief at any time in his life, if only someone had used the right words to explain it to him. Now, I doubt this. I doubt if one ever accepts a belief until one urgently needs it.

But, although Christopher wasn’t yet aware that he needed such a belief, he may have been feeling the need subconsciously. This would explain his recently increased hostility toward what he thought of as "religion" — the version of Christianity he had been taught in his childhood. Perhaps he was afraid that he would be forced to accept it, at last, after nearly fifteen years of atheism.- Ch. 15, p. 306

- As a homosexual, he had been wavering between embarrassment and defiance. He became embarrassed when he felt that he was making a selfish demand for his individual rights at a time when only group action mattered. He became defiant when he made the treatment of the homosexual a test by which every political party and government must be judged. His challenge to each one of them was: "All right, we've heard your liberty speech. Does that include us or doesn't it?"

The Soviet Union had passed this test with honors when it recognized the private sexual rights of the individual, in 1917. But, in 1934, Stalin's government had withdrawn this recognition and made all homosexual acts punishable by heavy prison sentences. It had agreed with the Nazis in denouncing homosexuality as a form of treason to the state. The only difference was that the Nazis called it "sexual Bolshevism" and the Communists "Fascist perversion."

Christopher — like many of his friends, homosexual and heterosexual — had done his best to minimize the Soviet betrayal of its own principles. After all, he had said to himself, anti-homosexual laws exist in most capitalist countries, including England and the United States. Yes — but if Communists claim that their system is juster than capitalism, doesn't that make their injustice to homosexuals less excusable and their hypocrisy even viler? He now realized that he must dissociate himself from the Communists, even as a fellow traveler. He might, in certain situations, accept them as allies but he could never regard them as comrades. He must never again give way to embarrassment, never deny the rights of his tribe, never apologize for its existence, never think of sacrificing himself masochistically on the altar of that false god of the totalitarians, the Greatest Good of the Greatest Number — whose priests are alone empowered to decide what "good" is.- Ch. 16, p. 334

- Suppose, Christopher now said to himself, I have a Nazi Army at my mercy. I can blow it up by pressing a button. The men in that Army are notorious for torturing and murdering civilians — all except for one of them, Heinz. Will I press the button? No — wait: Suppose I know that Heinz himself, out of cowardice or moral infection, has become as bad as they are and takes part in all their crimes? Will I press that button, even so? Christopher's answer, given without the slightest hesitation, was: Of course not.

That was a purely emotional reaction. But it helped Christopher think his way through to the next proposition. Suppose that Army goes into action and has just one casualty, Heinz himself. Will I press the button now and destroy his fellow criminals? No emotional reaction this time, but a clear answer, not to be evaded: Once I have refused to press that button because of Heinz, I can never press it. Because every man in that Army could be someone's Heinz and I have no right to play favorites. Thus Christopher was forced to recognize himself as a pacifist — although by an argument which he could only admit to with the greatest reluctance.- Ch. 16, p. 335

- I must honor those who fight of their own free willl, he said to himself. And I must try to imitate their courage by following my path as a pacifist, wherever it takes me.

- Ch. 16, p. 336

Quotes about Isherwood

[edit]- Barriers dissolve, too, when confronted by the Eastern poems: the poems of the sacred books, in Yeats' translation of the Upanishads, or Isherwood's of the Bhagavad-Gita, and such work as E. Powys Mathers' Black Marigolds and Robert Payne's The White Pony, a rich anthology of Chinese poetry.

- Muriel Rukeyser The Life of Poetry (1949)

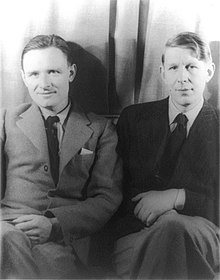

- Christopher’s kind are homosexuals, but more importantly, minorities of any sort, either tortured obscenely by the Nazis or rejected more hypocritically by social convention and snobbism. In his matter-of-fact treatment of his sexual preferences and affairs ("To Christopher, Berlin meant Boys," he announces at the start), Isherwood has made an important contribution to the literature of minority liberation. … Our age, like the Thirties, is given to strident political and artistic positions; while it would be wrong to condemn the more active spokesmen of minority rights, it is all the more significant that the tone (that most ineffable of all literary qualities) of Isherwood’s autobiography is neither truculent nor confessional, but the still, honest voice of a man looking back on the events of a tumultuous time. He shows how all minorities can be persecuted, by laws (the notorious paragraph 175 of the German penal code which made homosexual acts illegal), in social condescension (even from sympathetic parties, like Christopher’s mother), and most grotesquely, in self-hatred. The book’s central episode (the midpoint of the book brings us to the mid-point of the decade) deals with Isherwood’s inability to get his German boyfriend out of Germany; at the last moment, victory is snatched away when Heinz is refused entry by a British immigration official at Harwich in 1934. Christopher and Auden have gone to the pier, and after Heinz is turned back, Auden chillingly notes of the official: "As soon as I saw the bright-eyed little rat, I knew we were done for. He understood the whole situation at a glance — because he’s one of us."

Christopher and His Kind is a proclamation of the rights of "us," all of us, against the demands of "the others," whether fascists, aristocrats, war-makers, or the heterosexual hegemony, to live according to our natures.- Willard Spiegelman, in "The Liberation of Christopher Isherwood" in D magazine (March 1977)

External links

[edit]- Isherwood Exhibit at the Huntington

- "Christopher Isherwood, The Art of Fiction No. 49" interview with W. I. Scobie, in The Paris Review(Spring 1974)

- LitWeb.net: Christopher Isherwood Biography

- Christopher Isherwood Foundation

- Christopher Isherwood Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Huxley on Huxley. DVD recording.

- Where Joy Resides · An Isherwood Reader

- "Cabaret Berlin" · Information on Christopher Isherwood and the entertainment of the Weimar era

- Christopher Isherwood on IMDb