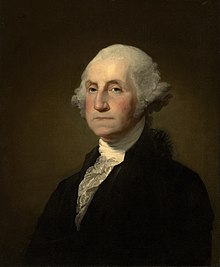

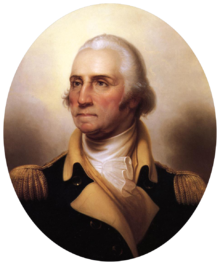

George Washington

George Washington (22 February 1732 – 14 December 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Second Continental Congress as commander of the Continental Army in June 1775, Washington led Patriot forces to victory in the American Revolutionary War and then served as president of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, which drafted and ratified the Constitution of the United States and established the American federal government. Washington has thus been called the "Father of his Country".

Quotes

[edit]

1750s

[edit]- Nothing is a greater stranger to my breast, or a sin that my soul more abhors, than that black and detestable one, ingratitude.

- Letter to Governor Dinwiddie (29 May 1754)

- Tis true, I profess myself a Votary to Love — I acknowledge that a Lady is in the Case — and further I confess, that this Lady is known to you. — Yes Madam, as well as she is to one, who is too sensible of her Charms to deny the Power, whose Influence he feels and must ever Submit to. I feel the force of her amiable beauties in the recollection of a thousand tender passages that I coud wish to obliterate, till I am bid to revive them. — but experience alas! sadly reminds me how Impossible this is. — and evinces an Opinion which I have long entertaind, that there is a Destiny, which has the Sovereign controul of our Actions — not to be resisted by the strongest efforts of Human Nature.

You have drawn me my dear Madam, or rather have I drawn myself, into an honest confession of a Simple Fact — misconstrue not my meaning — ’tis obvious — doubt it not, nor expose it, — the World has no business to know the object of my Love, declard in this manner to — you when I want to conceal it — One thing, above all things in this World I wish to know, and only one person of your Acquaintance can solve me that, or guess my meaning. — but adieu to this, till happier times, if I ever shall see them.- Letter to Mrs. George William Fairfax (Sally Cary Fairfax) (12 September 1758)

- Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable; procures success to the weak, and esteem to all.

- Letter of Instructions to the Captains of the Virginia Regiments (29 July 1759)

1770s

[edit]

- The General is sorry to be informed —, that the foolish and wicked practice of profane cursing and swearing, a vice heretofore little known in an American army, is growing into a fashion; — he hopes the officers will, by example as well as influence, endeavor to check it, and that both they and the men will reflect that we can have little hope of the blessing of Heaven on our arms, if we insult it by impiety and folly; added to this, it is a vice so mean and low, without any temptation, that every man of sense and character detests and despises it.

- Extract from the Orderly Book of the army under command of Washington, dated at Head Quarters, in the city of New York (3 August 1770); reported in American Masonic Register and Literary Companion, Volume 1 (1829), p. 163

- Unhappy it is though to reflect, that a Brother's Sword has been sheathed in a Brother's breast, and that, the once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with Blood, or Inhabited by Slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous Man hesitate in his choice?

- Letter to Mr. George William Fairfax (31 May 1775) George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress

- As to pay, Sir, I beg leave to assure the Congress that as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to accept this arduous employment at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it.

- But lest some unlucky event should happen unfavorable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.

- Washington's formal acceptance of command of the Army (16 June 1775), quoted in The Writings of George Washington : Life of Washington (1837) edited by Jared Sparks, p. 141

- When we assumed the Soldier, we did not lay aside the Citizen.

- George Washington to New York Legislature (26 June 1775)

- Every post is honorable in which a man can serve his country.

- Letter to Benedict Arnold (14 September 1775)

- The reflection upon my situation, and that of this army, produces many an uneasy hour, when all around me are wrapped in sleep. Few people know the predicament we are in, on a thousand accounts; fewer still will believe, if any disaster happens to these lines, from what cause it flows. I have often thought how much happier I should have been, if instead of accepting of a command under such circumstances, I had taken my musket upon my shoulders and entered the rank, or if I could have justified the measure of posterity, and my own conscience, had retired to the back country, and lived in a wigwam. If I shall be able to rise superior to these, and many other difficulties which might be enumerated, I shall most religiously believe that the finger of Providence is in it, to blind the eyes of our enemies; for surely if we get well through this month, it must be for want of their knowing the disadvantages we labor under. Could I have foreseen the difficulties which have come upon us, could I have known that such a backwardness would have been discovered in the old soldiers to the service, all the generals upon earth should not have convinced me of the propriety of delaying an attack upon Boston till this time.

- In a letter to Joseph Reed, during the siege of Boston (14 January 1776), quoted in History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill (1849) by Richard Frothingham, p. 286

- To expect … the same service from raw and undisciplined recruits, as from veteran soldiers, is to expect what never did and perhaps never will happen. Men, who are familiarized to danger, meet it without shrinking; whereas troops unused to service often apprehend danger where no danger is.

- Letter to the President of Congress (9 February 1776)

- Let us therefore animate and encourage each other, and show the whole world that a Freeman, contending for liberty on his own ground, is superior to any slavish mercenary on earth.

- General Orders, Headquarters, New York (2 July 1776)

- The General hopes and trusts that every officer and man will endeavor to live and act as becomes a Christian soldier defending the dearest rights and liberties of his country.

- General Order (9 July 1776) George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 3g Varick Transcripts

- The time is now near at hand which must probably determine whether Americans are to be freemen or slaves; whether they are to have any property they can call their own; whether their houses and farms are to be pillaged and destroyed, and themselves consigned to a state of wretchedness from which no human efforts will deliver them. The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die.

- Address to the Continental Army before the Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776)

- There is nothing that gives a man consequence, and renders him fit for command, like a support that renders him independent of everybody but the State he serves.

- Letter to the president of Congress, Heights of Harlem (24 September 1776)

- To place any dependence upon militia, is, assuredly, resting upon a broken staff. Men just dragged from the tender scenes of domestic life - unaccustomed to the din of arms - totally unacquainted with every kind of military skill, which being followed by a want of confidence in themselves when opposed to troops regularly trained, disciplined, and appointed, superior in knowledge, and superior in arms, makes them timid and ready to fly from their own shadows.

- Letter to the president of Congress, Heights of Harlem (24 September 1776)

- My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than can be reasonably expected; but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably can never do under any other circumstances.

- Encouraging his men to re-enlist in the army (31 December 1776)

- Parade with me my brave fellows, we will have them soon!

- Rallying his troops at the Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777)

- The Marquis de Lafayette is extremely solicitous of having a command equal to his rank. I do not know in what light Congress will view the matter, but it appears to me, from a consideration of his illustrious and important connexions, the attachment which he has manifested for our cause, and the consequences which his return in disgust might produce, that it will be advisable to gratify him in his wishes; and the more so, as several gentlemen from France, who came over under some assurances, have gone back disappointed in their expectations. His conduct with respect to them stands in a favorable point of view; having interested himself to remove their uneasiness, and urged the impropriety of their making any unfavorable representations upon their arrival at home; and in all his letters he has placed our affairs in the best situation he' could. Besides, he is sensible; discreet in his manners; has made great proficiency in our language; and, from the disposition he discovered at the battle of Brandywine, possesses a large share of bravery and military ardor.

- Letter to the Continental Congress (1 November 1777), as quoted in Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States Vol. 23, Issue 2 (1835), p. 665

- A great and lasting war can never be supported on this principle [patriotism] alone. It must be aided by a prospect of interest, or some reward.

- Letter to John Banister, Valley Forge (21 April 1778)

- While we are zealously performing the duties of good citizens and soldiers, we certainly ought not to be inattentive to the higher duties of religion. To the distinguished character of Patriot, it should be our highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian.

- General Orders (2 May 1778); published in Writings of George Washington (1932), Vol.XI, pp. 342-343

- It is not a little pleasing, nor less wonderful to contemplate, that after two years' manoeuvring and undergoing the strangest vicissitudes, that perhaps ever attended any one contest since the creation, both armies are brought back to the very point they set out from, and that which was the offending party in the beginning is now reduced to the use of the spade and pickaxe for defence. The hand of Providence has been so conspicuous in all this, that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations. But it will be time enough for me to turn preacher, when my present appointment ceases…

- Letter to Brigadier-General Nelson, 20 August 1778, in Ford's Writings of George Washington (1890), vol. VII, p. 161. Part of this is often attached to a fragment of a letter to John Armstrong of 11 March 1782; it is also often prefaced with the spurious "governing without God" sentence, as this 1867 example from Henry Wilson (Testimonies of American Statesmen and Jurists to the Truths of Christianity) shows:

- It is impossible to govern the world without God. It is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the Providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits and humbly implore his protection and favor. I am sure there never was a people who had more reason to acknowledge a divine interposition in their affairs, than those of the United States; and I should be pained to believe that they have forgotten that agency which was so often manifested during the revolution; or that they failed to consider the omnipotence of Him, who is alone able to protect them. He must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations.

- Letter to Brigadier-General Nelson, 20 August 1778, in Ford's Writings of George Washington (1890), vol. VII, p. 161. Part of this is often attached to a fragment of a letter to John Armstrong of 11 March 1782; it is also often prefaced with the spurious "governing without God" sentence, as this 1867 example from Henry Wilson (Testimonies of American Statesmen and Jurists to the Truths of Christianity) shows:

- It gives me very sincere pleasure to find that there is likely to be a coalition of the Whigs in your State (a few only excepted) and that the Assembly of it, are so well disposed to second your endeavors in bringing those murderers of our cause—the Monopolizers—forestallers—& Engrossers—to condign punishment. It is much to be lamented that each State, long ’ere this, has not hunted them down as the pests of Society, & the greatest enemies we have, to the happiness of America. I would to God that one of the most attrocious in each State was hung in Gibbets, up on a gallows five times as high as the one prepared by Haman—No punishment, in my opinion, is too great for the Man, who can build “his greatness upon his Country’s ruin.”

- George Washington to Joseph Reed, 12 December 1778, Founders Online, National Archives. Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 18, 1 November 1778 – 14 January 1779, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008, pp. 396–398. Page images at American Memory (Library of Congress)

- In the last place, though first in importance I shall ask—is there any thing doing, or that can be done to restore the credit of our currency? The depreciation of it is got to so alarming a point—that a waggon load of money will scarcely purchase a waggon load of provision.

- Letter to John Jay, 23 April 1779, Founders Online, National Archives. Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 20, 8 April–31 May 1779, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010, p. 177. Also found in The Life John Jay With Selections from His Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers. by His Son, William Jay in Two Volumes, Vol. II., 1833

- Few men have virtue to withstand the highest bidder.

- Letter to Major-General Robert Howe (17 August 1779), published in "The Writings of George Washington": 1778-1779, edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford (1890)

- Paraphrased variants:

- Few men have the virtue to withstand the highest bidder.

- Few men have virtue enough to withstand the highest bidder

- Know my good friend that no distance can keep anxious lovers long asunder, and that the wonders of former ages may be revived in this — But alas! will you not remark that amidst all the wonders recorded in holy writ no instance can be produced where a young Woman from real inclination has prefered an old man — This is so much against me that I shall not be able I fear to contest the prize with you — yet, under the encouragement you have given me I shall enter the list for so inestimable a jewell.

- Letter to the Marquis de Lafayette (30 September 1779)

- A slender acquaintance with the world must convince every man, that actions, not words, are the true criterion of the attachment of his friends, and that the most liberal professions of good will are very far from being the surest marks of it. I should be happy that my own experience had afforded fewer examples of the little dependence to be placed upon them.

- Letter to Major-General John Sullivan (15 December 1779), published in The Writings of George Washington (1890) by Worthington Chauncey Ford, Vol. 8, p. 139

Letter to John Hancock (1775)

[edit]- [F]ree Negroes who have served in this army are very much dissatisfied at being discarded. As it is to be apprehended that they may seek employ in the Ministerial Army, I have … given license for their being enlisted.

- To John Hancock (31 December 1775)

Letter to Phyllis Wheatley (1776)

[edit]

- Mrs. Phillis: Your favour of the 26th of October did not reach my hands 'till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurrences, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming, but not real neglect.

- I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. In honour of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the Poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the World this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of Vanity. This and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public Prints.

- If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favoured by the Muses, and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great Respect, etc.

Letter to Joseph Reed (1778)

[edit]- It gives me very sincere pleasure to find that there is likely to be a coalition … so well disposed to second your endeavours in bringing those murderers of our cause (the monopolizers, forestallers, and engrossers) to condign punishment. It is much to be lamented that each State long ere this has not hunted them down as the pests of society, and the greatest Enemys we have to the happiness of America. I would to God that one of the most attrocious of each State was hung in Gibbets upons a gallows five times as high as the one prepared by Haman. No punishment in my opinion is too great for the Man who can build his greatness upon his Country's ruin.

- Dec. 12, 1778 {also found at the Library of Congress}

- later misquoted against jews

- Dec. 12, 1778 {also found at the Library of Congress}

Letter to Henry Laurens (1779)

[edit]- I am not clear that a discrimination will not render slavery more irksome to those who remain in it. Most of the good and evil things in this life are judged of by comparison; and I fear a comparison in this case will be productive of much discontent in those who are held in servitude.

Letter to Edmund Pendleton (1779)

[edit]- … but I am under no apprehension of a capital injury from any other source than that of the continual depreciation of our Money.

This indeed is truly alarming, and of so serious a nature that every other effort is in vain unless something can be done to restore its credit.

..

Where this has been the policy (in Connecticut for instance) the prices of every article have fallen and the money consequently is in demand; but in the other States you can scarce get a single thing for it, and yet it is with-held from the public by speculators, while every thing that can be useful to the public is engrossed by this tribe of black gentry, who work more effectually against us that the enemys Arms; and are a hundd. times more dangerous to our liberties and the great cause we are engaged in.- Nov. 1, 1779 (the original was previously in the Library of Congress's online service} Template:Unreliable source?

- later misquoted against jews

- Nov. 1, 1779 (the original was previously in the Library of Congress's online service} Template:Unreliable source?

1780s

[edit]

- [A]bolish the name and appearance of a Black Corps.

- Recommendations to reorganize two Rhode Island regiments into integrated rather than segregated groups, in a letter to Major General William Heath (29 July 1780), in The Writings of George Washington, 19:93. According to historian Robert A. Selig, the Continental Army exhibited a degree of integration not reached by the American army again for 200 years (until after World War II).

- Example, whether it be good or bad, has a powerful influence.

- Letter to Lord Stirling (5 March 1780)

- The many remarkable interpositions of the divine government, in the hours of our deepest distress and darkness, have been too luminous to suffer me to doubt the happy issue of the present contest.

- Letter to General Armstrong (26 March 1781), as quoted in The Religious Opinions and Character of Washington (1836) by Edward Charles McGuire, p. 122

- The Commander in Chief earnestly recommends that the troops not on duty should universally attend with that seriousness of Deportment and gratitude of Heart which the recognition of such reiterated and astonishing interpositions of Providence demand of us.

- Notes on general orders to the troops, (20 October 1781), as quoted in The Writings of George Washington (1835) edited by Jared Sparks, Vol. 8, p. 189

- Without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive. And with it, everything honorable and glorious.

- To the Marquis de Lafayette (15 November 1781)

- I am sure there never was a people, who had more reason to acknowledge a divine interposition in their affairs, than those of the United States; and I should be pained to believe, that they have forgotten that agency, which was so often manifested during our revolution, or that they failed to consider the omnipotence of that God, who is alone able to protect them.

- Letter to John Armstrong, 11 March 1782, in Ford's Writings of George Washington (1891), vol. XII, p. 111. This is frequently attached to part of a letter to Brigadier-General Nelson of 20 August 1778, as in this 1864 example from B. F. Morris, The Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, pp. 33-34:

- I am sure that there never was a people who had more reason to acknowledge a divine interposition in their affairs than those of the United States; and I should be pained to believe that they have forgotten that agency which was so often manifested during the Revolution, or that they failed to consider the omnipotence of that God who is alone able to protect them. He must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligations.

- Letter to John Armstrong, 11 March 1782, in Ford's Writings of George Washington (1891), vol. XII, p. 111. This is frequently attached to part of a letter to Brigadier-General Nelson of 20 August 1778, as in this 1864 example from B. F. Morris, The Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, pp. 33-34:

- Be courteous to all, but intimate with few, and let those few be well tried before you give them your confidence; true friendship is a plant of slow growth, and must undergo and withstand the shocks of adversity before it is entitled to the appellation.

- Letter to Bushrod Washington (15 January 1783)

- Do not conceive that fine Clothes make fine Men, any more than fine feathers make fine Birds—A plain genteel dress is more admired and obtains more credit than lace & embroidery in the Eyes of the judicious and sensible.

- Letter to Bushrod Washington (15 January 1783)

- Happy, thrice happy shall they be pronounced hereafter, who have contributed any thing, who have performed the meanest office in erecting this stupendous fabrick of Freedom and Empire on the broad basis of Independency; who have assisted in protecting the rights of humane nature and establishing an Asylum for the poor and oppressed of all nations and religions.

- General Orders (18 April 1783)

- It may be laid down, as a primary position, and the basis of our system, that every citizen who enjoys the protection of a free government, owes not only a proportion of his property, but even of his personal services to the defence of it, and consequently that the Citizens of America (with a few legal and official exceptions) from 18 to 50 Years of Age should be borne on the Militia Rolls, provided with uniform Arms, and so far accustomed to the use of them, that the Total strength of the Country might be called forth at Short Notice on any very interesting Emergency.

- "Sentiments on a Peace Establishment" in a letter to Alexander Hamilton (2 May 1783); published in The Writings of George Washington (1938), edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 26, p. 289

- The scheme, my dear Marqs., which you propose as a precedent to encourage the emancipation of the black people of this Country from that state of Bondage in wch. they are held, is a striking evidence of the benevolence of your Heart. I shall be happy to join you in so laudable a work; but will defer going into a detail of the business, till I have the pleasure of seeing you.

- " TO THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS." in a letter to Thomas Mifflin (17 JUNE 1783); published in The Writings of George Washington (1938), edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 26, p. 294

- Arbitrary power is most easily established on the ruins of liberty abused to licentiousness.

- I now make it my earnest prayer, that God would have you, and the State over which you preside, in his holy protection; that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to Government; to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large; and, particularly, for their brethren who have served in the Geld; and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility, and pacifick temper of the mind, which were the characteristicks of the divine Author of our blessed religion ; without an humble imitation of whose example, in these things, we can never hope to be a happy Nation.

- Circular Letter to the Governours of the several States (18 June 1783). Misreported as "I make it my constant prayer that God would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility, and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion; without a humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy nation", in Josiah Hotchkiss Gilbert, Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895), p. 315

- The bosom of America is open to receive not only the Opulent and respectable Stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations And Religions; whom we shall wellcome to a participation of all our rights and previleges, if by decency and propriety of conduct they appear to merit the enjoyment.

- Letter to the members of the Volunteer Association and other Inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ireland who have lately arrived in the City of New York (2 December 1783), as quoted in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington (1938), vol. 27, p. 254

- Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.

- Address to Congress resigning his commission (23 December 1783)

- I am become a private citizen on the banks of the Potomac, and under the shadow of my own Vine and my own Fig-tree, free from the bustle of a camp and the busy scenes of public life, I am solacing myself with those tranquil enjoyments, of which the Soldier who is ever in pursuit of fame, the Statesman whose watchful days and sleepless nights are spent in devising schemes to promote the welfare of his own, perhaps the ruin of other countries, as if this globe was insufficient for us all, and the Courtier who is always watching the countenance of his Prince, in hopes of catching a gracious smile, can have very little conception. I am not only retired from all public employments, but I am retiring within myself; and shall be able to view the solitary walk, and tread the paths of private life with heartfelt satisfaction. Envious of none, I am determined to be pleased with all; and this my dear friend, being the order for my march, I will move gently down the stream of life, until I sleep with my Fathers.

- Letter to Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1 February 1784)

- A people... who are possessed of the spirit of commerce, who see and who will pursue their advantages may achieve almost anything.

- Letter to Benjamin Harrison V (10 October 1784)

- [T]he motives which predominate most in human affairs is self-love and self-interest.

- Letter to James Madison (3 December 1784) as quoted in Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington (2008) by Peter R. Henriques, p. 139.

- Men's minds are as variant as their faces, and, where the motives of their actions are pure, the operation of the former is no more to be imputed to them as a crime, than the appearance of the latter; for both, being the work of nature, are alike unavoidable.

- Letter to Benjamin Harrison V (9 March 1789), published in Washington's Writings: Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original Manuscripts, Volume IX, p. 475.

- Democratical States must always feel before they can see: it is this that makes their Governments slow, but the people will be right at last.

- Letter to the Marquis de Lafayette (25 July 1785)

- As the complexion of European politics seems now (from letters I have received from the Marqs. de la Fayette, Chevrs. Chartellux, De la Luzerne, &c.,) to have a tendency to Peace, I will say nothing of war, nor make any animadversions upon the contending powers; otherwise, I might possibly have said that the retreat from it seemed impossible after the explicit declaration of the parties: My first wish is to see this plague to mankind banished from off the Earth, and the sons and Daughters of this world employed in more pleasing and innocent amusements, than in preparing implements and exercising them for the destruction of mankind: rather than quarrel about territory let the poor, the needy and oppressed of the Earth, and those who want Land, resort to the fertile plains of our western country, the second Promise, and there dwell in peace, fulfilling the first and great commandment.

- Letter to David Humphreys (25 July 1785), published in The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 28, pp. 202-3. The W. W. Abbot transcription (given at Founders Online) differs slightly:

- My first wish is, to see this plague to Mankind banished from the Earth; & the Sons & daughters of this World employed in more pleasing & innocent amusements than in preparing implements, & exercising them for the destruction of the human race.

- Letter to David Humphreys (25 July 1785), published in The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 28, pp. 202-3. The W. W. Abbot transcription (given at Founders Online) differs slightly:

- We are either a united people, or we are not. If the former, let us, in all matters of general concern act as a Nation, which have national objects to promote, and a national character to support. If we are not, let us no longer act a farce by pretending to it.

- My manner of living is plain. I do not mean to be put out of it. A glass of wine and a bit of mutton are always ready; and such as will be content to partake of them are always welcome. Those, who expect more, will be disappointed, but no change will be effected by it.

- Letter to George William Fairfax (25 June 1786), published in The Writings Of George Washington (1835) by Jared Sparks, p. 175

- There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery.

- Letter to Robert Morris (12 April 1786)

- If you tell the Legislatures they have violated the treaty of peace and invaded the prerogatives of the confederacy they will laugh in your face. What then is to be done? Things cannot go on in the same train forever. It is much to be feared, as you observe, that the better kind of people being disgusted with the circumstances will have their minds prepared for any revolution whatever. We are apt to run from one extreme into another. To anticipate & prevent disasterous contingencies would be the part of wisdom & patriotism.

What astonishing changes a few years are capable of producing! I am told that even respectable characters speak of a monarchical form of government without horror. From thinking proceeds speaking, thence to acting is often but a single step. But how irrevocable & tremendous! What a triumph for the advocates of despotism to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves, and that systems founded on the basis of equal liberty are merely ideal & falacious! Would to God that wise measures may be taken in time to avert the consequences we have but too much reason to apprehend.

Retired as I am from the world, I frankly acknowledge I cannot feel myself an unconcerned spectator. Yet having happily assisted in bringing the ship into port & having been fairly discharged; it is not my business to embark again on a sea of troubles. Nor could it be expected that my sentiments and opinions would have much weight on the minds of my Countrymen — they have been neglected, tho' given as a last legacy in the most solemn manner. I had then perhaps some claims to public attention. I consider myself as having none at present.

- Altho’ I pretend to no peculiar information respecting commercial affairs, nor any foresight into the scenes of futurity; yet as the member of an infant-empire, as a Philanthropist by character, and (if I may be allowed the expression) as a Citizen of the great republic of humanity at large; I cannot help turning my attention sometimes to this subject. I would be understood to mean, I cannot avoid reflecting with pleasure on the probable influence that commerce may here after have on human manners & society in general. On these occasions I consider how mankind may be connected like one great family in fraternal ties—I endulge a fond, perhaps an enthusiastic idea, that as the world is evidently much less barbarous than it has been, its melioration must still be progressive—that nations are becoming more humanized in their policy—that the subjects of ambition & causes for hostility are daily diminishing—and in fine, that the period is not very remote when the benefits of a liberal & free commerce will, pretty generally, succeed to the devastations & horrors of war.

- “From George Washington to Lafayette, 15 August 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives Source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 4, 2 April 1786 – 31 January 1787, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, pp. 214–216. Page scan at American Memory (Library of Congress)

- If they have real grievances redress them, if possible; or acknowledge the justice of them, and your inability to do it at the moment. If they have not, employ the force of government against them at once.

- Letter to Henry Lee (31 October 1786)

- Paper money has had the effect in your State that it ever will have, to ruin commerce—oppress the honest, and open a door to every species of fraud and injustice.

- Letter to Jabez Bowen (9 January 1787)

- The only stipulations I shall contend for are, that in all things you shall do as you please. I will do the same; and that no ceremony may be used or any restraint be imposed on any one.

- Letter to David Humphreys, inviting him to an indefinite stay at Mt. Vernon (10 October 1787), as published in Life and Times of David Humphreys (1917) by Frank Landon Humphreys, Vol. I, p. 426

- Liberty, when it begins to take root, is a plant of rapid growth.

- Letter to James Madison (2 March 1788)

- Your young military men, who want to reap the harvest of laurels, don't care (I suppose) how many seeds of war are sown; but for the sake of humanity it is devoutly to be wished, that the manly employment of agriculture and the humanizing benefits of commerce, would supersede the waste of war and the rage of conquest; that the swords might be turned into plough-shares, the spears into pruning hooks, and, as the Scripture expresses it, "the nations learn war no more."

- Letter to Marquis de Chastellux (25 April 1788), published in The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 29, p. 485

- I hope I shall always possess firmness and virtue enough to maintain (what I consider the most enviable of all titles) the character of an honest man, as well as prove (what I desire to be considered in reality) that I am, with great sincerity & esteem, Dear Sir Your friend and Most obedient Hble Ser⟨vt⟩

- The unfortunate condition of the persons, whose labour in part I employed, has been the only unavoidable subject of regret. To make the Adults among them as easy & as comfortable in their circumstances as their actual state of ignorance & improvidence would admit; & to lay a foundation to prepare the rising generation for a destiny different from that in which they were born; afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.

- Comment of late 1788 or early 1789 upon his slaves, as recorded by David Humphreys, in his notebooks on his conversations with Washington, now in the Rosenbach Library in Philadelphia

- The blessed Religion revealed in the word of God will remain an eternal and awful monument to prove that the best Institutions may be abused by human depravity; and that they may even, in some instances be made subservient to the vilest of purposes. Should, hereafter, those who are intrusted with the management of this government, incited by the lust of power & prompted by the supineness or venality of their Constituents, overleap the known barriers of this Constitution and violate the unalienable rights of humanity: it will only serve to shew, that no compact among men (however provident in its construction & sacred in its ratification) can be pronounced everlasting and inviolable—and if I may so express myself, that no wall of words—that no mound of parchmt can be so formed as to stand against the sweeping torrent of boundless ambition on the one side, aided by the sapping current of corrupted morals on the other.

- p. 34 of a draft of a discarded and undelivered version of his first inaugural address (30 April 1789)

- Such being the impressions under which I have, in obedience to the public summons, repaired to the present station; it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official Act, my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the Universe, who presides in the Councils of Nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that his benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the People of the United States, a Government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes: and may enable every instrument employed in its administration to execute with success, the functions allotted to his charge. In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own; nor those of my fellow-citizens at large, less than either. No People can be bound to acknowledge and adore the invisible hand, which conducts the Affairs of men more than the People of the United States. Every step, by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation, seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency. And in the important revolution just accomplished in the system of their United Government, the tranquil deliberations and voluntary consent of so many distinct communities, from which the event has resulted, cannot be compared with the means by which most Governments have been established, without some return of pious gratitude along with an humble anticipation of the future blessings which the past seem to presage.

- First Inaugural Address (30 April 1789), published in The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 30, pp. 292-3

- I dwell on this prospect with every satisfaction which an ardent love for my Country can inspire: since there is no truth more thoroughly established, than that there exists in the oeconomy and course of nature, an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness, between duty and advantage, between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy, and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity: Since we ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven, can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained: And since the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.

- First Inaugural Address (30 April 1789), published in The Writings of George Washington, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Vol. 30, pp. 294-5

- For myself the delay may be compared with a reprieve; for in confidence I assure you, with the world it would obtain little credit that my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares, to quit a peaceful abode for an Ocean of difficulties, without that competency of political skill, abilities and inclination which is necessary to manage the helm.

- Comment to General Henry Knox on the delay in assuming office (March 1789)

- In executing the duties of my present important station, I can promise nothing but purity of intentions, and, in carrying these into effect, fidelity and diligence.

- Message to the U.S. Congress (9 July 1789); The Writings of George Washington: Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private (1837) edited by Jared Sparks, p. 159 (PDF)

- The satisfaction arising from the indulgent opinion entertained by the American People of my conduct, will, I trust, be some security for preventing me from doing any thing, which might justly incur the forfeiture of that opinion. And the consideration that human happiness and moral duty are inseparably connected, will always continue to prompt me to promote the progress of the former, by inculcating the practice of the latter.

- Letter to the Protestant Episcopal Church (19 August 1789) Scan at American Memory (Library of Congress).

- Impressed with a conviction that the due administration of justice is the firmest pillar of good Government, I have considered the first arrangement of the Judicial department as essential to the happiness of our Country, and to the stability of its political system; hence the selection of the fittest characters to expound the law, and dispense justice, has been an invariable object of my anxious concern.

- Letter to U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph (28 September 1789), as published in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 edited by John C. Fitzpatrick

- The inscription on the facade of the New York Supreme Court court house in New York County is a misquotation from the above letter: "The true administration of justice is the firmest pillar of good government." See "George Denied His Due" by Bruce Golding, in the New York Post (16 February 2009)

- Letter to U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph (28 September 1789), as published in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 edited by John C. Fitzpatrick

The Newburgh Address (1783)

[edit]

- Washington's response to the Newburgh Conspiracy, known as Newburgh Address (15 March 1783) · Online edition at the National Archives · The anonymous Newburgh letter, followed by Washington's response at Early America Milestones

- Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for, I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.

- Statement as he put on his glasses before delivering his response to the first Newburgh Address (15 March 1783), quoted in a letter from General David Cobb to Colonel Timothy Pickering (25 November 1825)

- The Author of the piece, is entitled to much credit for the goodness of his Pen: and I could wish he had as much credit for the rectitude of his Heart — for, as Men see thro’ different Optics, and are induced by the reflecting faculties of the Mind, to use different means to attain the same end; the Author of the Address, should have had more charity, than to mark for Suspicion, the Man who should recommend Moderation and longer forbearance — or, in other words, who should not think as he thinks, and act as he advises. But he had another plan in view, in which candor and liberality of Sentiment, regard to justice, and love of Country, have no part; and he was right, to insinuate the darkest suspicion, to effect the blackest designs.

That the Address is drawn with great art, and is designed to answer the most insidious purposes. That it is calculated to impress the Mind, with an idea of premeditated injustice in the Sovereign power of the United States, and rouse all those resentments which must unavoidably flow from such a belief. That the secret Mover of this Scheme (whoever he may be) intended to take advantage of the passions, while they were warmed by the recollection of past distresses, without giving time for cool, deliberative thinking, & that composure of Mind which is so necessary to give dignity & stability to measures, is rendered too obvious, by the mode of conducting the business, to need other proof than a reference to the proceeding.

- There might, Gentlemen, be an impropriety in my taking notice, in this Address to you, of an anonymous production — but the manner in which that performance has been introduced to the Army — the effect it was intended to have, together with some other circumstances, will amply justify my observations on the tendency of that Writing. With respect to the advice given by the Author — to suspect the Man, who shall recommend moderate measures and longer forbearance — I spurn it — as every Man, who regards that liberty, & reveres that Justice for which we contend, undoubtedly must — for if Men are to be precluded from offering their sentiments on a matter, which may involve the most serious and alarming consequences, that can invite the consideration of Mankind; reason is of no use to us — the freedom of Speech may be taken away — and, dumb & silent we may be led, like sheep, to the Slaughter.

- You will, by the dignity of your Conduct, afford occasion for Posterity to say, when speaking of the glorious example you have exhibited to Mankind, had this day been wanting, the World had never seen the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining.

1790s

[edit]

- The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for giving to Mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.- Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island (1790)

- To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.

- First Annual Address, to both Houses of Congress (8 January 1790).

- Compare: "Qui desiderat pacem præparet bellum" (translated: "Who would desire peace should be prepared for war"), Vegetius, Rei Militari 3, Prolog.; "In pace, ut sapiens, aptarit idonea bello" (translated: "In peace, as a wise man, he should make suitable preparation for war"), Horace, Book ii. satire ii.

- The advancement of agriculture, commerce and manufactures, by all proper means, will not, I trust, need recommendation. But I cannot forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad, as to the exertions of skill and genius in producing them at home; and of facilitating the intercourse between the distant parts of our country by a due attention to the Post Office and Post Roads.

- First Annual Address, to both House of Congress (8 January 1790)

- A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined; to which end a uniform and well-digested plan is requisite; and their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies.

- First Annual Address, to both House of Congress (8 January 1790)

- All see, and most admire, the glare which hovers round the external trappings of elevated office. To me there is nothing in it, beyond the lustre which may be reflected from its connection with a power of promoting human felicity.

- Letter to Catherine Macaulay Graham (9 January 1790)

- As mankind become more liberal they will be more apt to allow, that all those who conduct themselves as worthy members of the Community are equally entitled to the protection of civil Government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality.

- Letter to Roman Catholics (15 March 1790)

- [A] good moral character is the first essential in a man, and that the habits contracted at your age are generally indelible, and your conduct here may stamp your character through life. It is therefore highly important that you should endeavor not only to be learned but virtuous.

- Letter to Steptoe Washington (5 December 1790)

- It is better to offer no excuse than a bad one.

- Letter to his niece, Harriet Washington (30 October 1791)

- Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause; and I was not without hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy of the present age would have put an effectual stop to contentions of this kind.

- Letter to Sir Edward Newenham (22 June 1792) as published in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (1939) as edited by John Clement Fitzpatrick

- Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind, those which are caused by difference of sentiments in religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing, and ought most to be deprecated. I was in hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy, which has marked the present age, would at least have reconciled Christians of every denomination so far that we should never again see the religious disputes carried to such a pitch as to endanger the peace of society.

- Letter to Edward Newenham (20 October 1792), these statements and one from a previous letter to Newenham seem to have become combined and altered into a misquotation of Washington's original statements to read:

- Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause. I had hoped that liberal and enlightened thought would have reconciled the Christians so that their religious fights would not endanger the peace of Society.

- As misquoted in The Conservative Soul: How We Lost It, How to Get It Back (2006) by Andrew Sullivan, p. 131

- Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause. I had hoped that liberal and enlightened thought would have reconciled the Christians so that their religious fights would not endanger the peace of Society.

- Flattering as it may be to the human mind, & truly honorable as it is to receive from our fellow citizens testimonies of approbation for exertions to promote the public welfare; it is not less pleasing to know that the milder virtues of the heart are highly respected by a society whose liberal principles must be founded in the immediate laws of truth and justice. To enlarge the sphere of social happiness is worthy the benevolent design of the Masonic Institution; and it is most fervently to be wished, that the conduct of every member of the fraternity, as well as those publications which discover the principles which actuate them may tend to convince Mankind that the grand object of Masonry is to promote the happiness of the human race.

- Letter to the Grand Lodge of Free Masons of Massachusetts (27 December 1792), published in The Writings Of George Washington (1835) by Jared Sparks, p. 201

- We have abundant reason to rejoice, that, in this land, the light of truth and reason has triumphed over the power of bigotry and superstition, and that every person may here worship God according to the dictates of his own heart. In this enlightened age, & in this land of equal liberty, it is our boast, that a man's religious tenets will not forfeit the protection of the laws, nor deprive him of the right of attaining & holding the highest offices that are known in the United States.

Your prayers for my present and future felicity are received with gratitude; and I sincerely wish, Gentlemen, that you may in your social and individual capacities taste those blessings, which a gracious God bestows upon the righteous.- Letter to the members of The New Church in Baltimore (22 January 1793), published in The Writings Of George Washington (1835) by Jared Sparks, p. 201

- The friends of humanity will deprecate War, wheresoever it may appear; and we have experience enough of its evils, in this country, to know, that it should not be wantonly or unnecessarily entered upon. I trust, that the good citizens of the United States will show to the world, that they have as much wisdom in preserving peace at this critical juncture, as they have hitherto displayed valor in defending their just rights.

- Address to the merchants of Philadelphia (16 May 1793), published in The Writings Of George Washington (1835) by Jared Sparks, p. 202

- If we desire to avoid insult, we must be able to repel it; if we desire to secure peace, one of the most powerful instruments of our rising prosperity, it must be known that we are at all times ready for war

- Fifth annual Message (3 December 1793)

- I am very glad to hear that the Gardener has saved so much of the St. foin seed, and that of the India Hemp. Make the most you can of both, by sowing them again in drills. . . Let the ground be well prepared, and the Seed (St. foin) be sown in April. The Hemp may be sown any where.

- George Washington in a letter to William Pearce at Mount Vernon (Philadelphia 24th Feby 1794), The Writings of George Washington, Bicentennial Edition 1939, p.279 books.google, and founders.archives.gov

- This quote is often confused with Make the most of the Indian hemp seed, and sow it everywhere! George Washington Spurious Quotations

- When one side only of a story is heard and often repeated, the human mind becomes impressed with it insensibly.

- Letter to Edmund Pendleton (22 January 1795)

- Malignity, therefore, may dart its shafts, but no earthly power can deprive me of the consolation of knowing that I have not, in the whole course of my Administration (however numerous they may have been) committed an intentional error.

- Letter to David Humphreys (12 June 1796)

- Rise early, that by habit it may become familiar, agreeable, healthy, and profitable. It may, for a while, be irksome to do this, but that will wear off; and the practice will produce a rich harvest forever thereafter; whether in public or private walks of life.

- Letter to George Washington Parke Custis (7 January 1798)

- It is infinitely better to have a few good men than many indifferent ones.

- Letter to James McHenry (10 August 1798)

- I have heard much of the nefarious, & dangerous plan, & doctrines of the Illuminati, but never saw the Book until you were pleased to send it to me. The same causes which have prevented my acknowledging the receipt of your letter, have prevented my reading the Book, hitherto; namely — the multiplicity of matters which pressed upon me before, & the debilitated state in which I was left after, a severe fever had been removed. And which allows me to add little more now, than thanks for your kind wishes and favourable sentiments, except to correct an error you have run into, of my Presiding over the English lodges in this Country. The fact is, I preside over none, nor have I been in one more than once or twice, within the last thirty years. I believe notwithstandings, that none of the Lodges in this Country are contaminated with the principles ascribed to the Society of the Illuminati.

- Letter to Reverend G. W. Snyder (25 September 1798) thanking him for a copy of Proofs of a Conspiracy against All the Religions and Governments of Europe (1798) by John Robison.

- You could as soon as scrub the blackamore white, as to change the principles of a profest Democrat; and that he will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the Government of this Country.

- The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, Vol. 36, August 4, 1797-October 28, 1798 (letter written, 30 September 1798, Mount Vernon) p. 474

- It was not my intention to doubt that, the Doctrines of the Illuminati, and principles of Jacobinism had not spread in the United States. On the contrary, no one is more truly satisfied of this fact than I am.

The idea that I meant to convey, was, that I did not believe that the Lodges of Free Masons in this Country had, as Societies, endeavoured to propagate the diabolical tenets of the first, or pernicious principles of the latter (if they are susceptible of seperation). That Individuals of them may have done it, or that the founder, or instrument employed to found, the Democratic Societies in the United States, may have had these objects; and actually had a seperation of the People from their Government in view, is too evident to be questioned.

- So far as I am acquainted with the principles & Doctrines of Free Masonry, I conceive it to be founded in benevolence and to be exercised only for the good of mankind. If it has been a Cloak to promote improper or nefarious objects, it is a melancholly proof that in unworthy hands, the best institutions may be made use of to promote the worst designs.

- As mankind become more liberal they will be more apt to allow that all those who conduct themselves as worthy members of the community are equally entitled to the protection of civil government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality.

- Letter to the Roman Catholics in America (15 March 1790)

- To sell the overplus I cannot, because I am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species. To hire them out, is almost as bad, because they could not be disposed of in families to any advantage, and to disperse the families I have an aversion. What then is to be done? Something must or I shall be ruined; for all the money (in addition to what I raise by Crops, and rents) that have been received for Lands, sold within the last four years, to the amount of Fifty thousand dollars, has scarcely been able to keep me a float.

- Letter to Robert Lewis, 18 August 1799, published in John Clement Fitzpatrick, The writings of George Washington from the original manuscript sources, volume 37, pp. 338-9

- I die hard but am not afraid to go. I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it — my breath cannot last long.

- The first sentence here is sometimes presented as being his last statement before dying, but they are reported as part of the fuller statement, and as being said in the afternoon prior to his death in Life of Washington (1859) by Washington Irving, and his actual last words are stated to have been those reported by Tobias Lear below.

- Tis well.

- Washington's last words, as recorded by Tobias Lear, in his journal (14 December 1799). Washington said this after being satisfied that precautions would be taken against his being buried prematurely:

- About ten o'clock he made several attempts to speak to me before he could effect it, at length he said, — "I am just going. Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead." I bowed assent, for I could not speak. He then looked at me again and said, "Do you understand me? I replied "Yes." "Tis well" said he.

- A conflation of the last two quotes has also sometimes been reported as his last statement: "It is well. I die hard but am not afraid to go".

- About ten o'clock he made several attempts to speak to me before he could effect it, at length he said, — "I am just going. Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the Vault in less than three days after I am dead." I bowed assent, for I could not speak. He then looked at me again and said, "Do you understand me? I replied "Yes." "Tis well" said he.

Letter to Catharine Macaulay Graham (1790)

[edit]- Letter to Catharine Macaulay Graham (9 January 1790), New York.

- The establishment of our new government seemed to be the last great experiment for promoting human happiness by a reasonable compact in civil society. It was to be in the first instance, in a considerable degree, a government of accommodation as well as a government of laws. Much was to be done by prudence, much by conciliation, much by firmness. Few, who are not philosophical spectators, can realize the difficult and delicate part, which a man in my situation had to act. All see, and most admire, the glare which hovers round the external happiness of elevated office. To me there is nothing in it beyond the lustre, which may be reflected from its connection with a power of promoting human felicity.

To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, 18 August 1790

[edit]- From George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, 18 August 1790, National Archives and Records Administration.

- The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet, from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security. If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good Government, to become a great and happy people.

- The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

- May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.

Farewell Address (1796)

[edit]

- Every day the increasing weight of years admonishes me more and more, that the shade of retirement is as necessary to me as it will be welcome. Satisfied, that, if any circumstances have given peculiar value to my services, they were temporary, I have the consolation to believe, that, while choice and prudence invite me to quit the political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.

- Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.

The unity of Government, which constitutes you one people, is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquillity at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty, which you so highly prize.

- It is of infinite moment, that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the Palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion, that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

- While, then, every part of our country thus feels an immediate and particular interest in Union, all the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means and efforts greater strength, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger, a less frequent interruption of their peace by foreign nations; and, what is of inestimable value, they must derive from Union an exemption from those broils and wars between themselves, which so frequently afflict neighbouring countries not tied together by the same governments, which their own rivalships alone would be sufficient to produce, but which opposite foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues would stimulate and embitter. Hence, likewise, they will avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments, which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to Republican Liberty. In this sense it is, that your Union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear to you the preservation of the other.

- One of the expedients of party to acquire influence, within particular districts, is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heart-burnings, which spring from these misrepresentations; they tend to render alien to each other those, who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection.

- To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a Government for the whole is indispensable. No alliances, however strict, between the parts can be an adequate substitute; they must inevitably experience the infractions and interruptions, which all alliances in all times have experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth, you have improved upon your first essay, by the adoption of a Constitution of Government better calculated than your former for an intimate Union, and for the efficacious management of your common concerns.

- The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish Government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established Government.

- I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the state, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party, generally.

- The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries, which result, gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.

- The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the Public Councils, and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.

- If in the opinion of the People, the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed.

- Of all the dispositions and habits, which lead to political prosperity, Religion and Morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and Citizens. The mere Politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connexions with private and public felicity.

- The Internet document known as "History Forgotten" or "Forsaken Roots" misquotes the opening of this section as follows: "It is impossible to govern the world without God and the Bible. Of all the dispositions and habits that lead to political prosperity, our religion and morality are the indispensable supports."

- Let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

- It is substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to every species of free government.

- Promote, then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

- As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is, to use it as sparingly as possible; avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it; avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertions in time of peace to discharge the debts, which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burthen, which we ourselves ought to bear.

- Observe good faith and justice towards all Nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all. Religion and Morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be, that good policy does not equally enjoin it? It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and, at no distant period, a great Nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence. Who can doubt, that, in the course of time and things, the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any temporary advantages, which might be lost by a steady adherence to it? Can it be, that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a Nation with its Virtue?

- In the execution of such a plan, nothing is more essential, than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular Nations, and passionate attachments for others, should be excluded; and that, in place of them, just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation, which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. Antipathy in one nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable, when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate, envenomed, and bloody contests.

- So likewise, a passionate attachment of one Nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favorite Nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest, in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter, without adequate inducement or justification. It leads also to concessions to the favorite Nation of privileges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the Nation making the concessions; by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained; and by exciting jealousy, ill-will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld. And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens, (who devote themselves to the favorite nation,) facility to betray or sacrifice the interests of their own country, without odium, sometimes even with popularity; gilding, with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation, a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.

- Real Patriots, who may resist the intrigues of the favourite, are liable to become suspected and odious; while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people, to surrender their interests. (Note: spelling/capitalization likely original.[1]).

- The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is, in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connexion as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.

- 'Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it; for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements. I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy. I repeat it, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But, in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

- There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favors from nation to nation.

- Harmony, liberal intercourse with all nations, are recommended by policy, humanity, and interest.

- In offering to you, my countrymen, these counsels of an old and affectionate friend, I dare not hope they will make the strong and lasting impression I could wish; that they will control the usual current of the passions, or prevent our nation from running the course, which has hitherto marked the destiny of nations. But, if I may even flatter myself, that they may be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good; that they may now and then recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to warn against the mischiefs of foreign intrigue, to guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism; this hope will be a full recompense for the solicitude for your welfare, by which they have been dictated.

- This has sometimes been misquoted as: Guard against the postures of pretended patriotism.

- The duty of holding a neutral conduct may be inferred, without any thing more, from the obligation which justice and humanity impose on every nation, in cases in which it is free to act, to maintain inviolate the relations of peace and amity towards other nations.

- Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope, that my Country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that, after forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

Posthumous attributions

[edit]