American Revolution

Appearance

(Redirected from Revolutionary War)

The American Revolution was a period during the last half of the 18th century in which the Thirteen Colonies gained independence from the British Empire and became the United States of America. In this period, the colonies united against the British Empire and entered into the armed conflict known as the American Revolutionary War (or the "American War of Independence" in British parlance), between 1775 and 1783. This resulted in the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and victory on the battlefield in October 1781.

Preludes to Independence

[edit]

- For if our Trade may be taxed, why not our Lands? Why not the Produce of our Lands & everything we possess or make use of? This we apprehend annihilates our Charter Right to govern & tax ourselves. It strikes at our British privileges, which as we have never forfeited them, we hold in common with our Fellow Subjects who are Natives of Britain. If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal Representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?

- Samuel Adams, as quoted in Radical Puritan, by Fowler, 51–52.

- Let us see delineated before us the true map of man. Let us hear the dignity of his nature, and the noble rank he holds among the works of God—that consenting to slavery is a sacrilegious breach of trust, as offensive in the sight of God as it is derogatory from our own honor or interest or happiness.

- John Adams, Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law (1765), as quoted in Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, 1865), 3:462–3.

- As to the history of the revolution, my ideas may be peculiar, perhaps singular. What do we mean by the revolution? The war? That was no part of the revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years, before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington.

- John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson (24 August 1815); in Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams (1856), vol. 10, p. 172.

- Then join hand in hand, brave Americans all! By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall.

- John Dickinson, The Liberty Song (July 1768)

- Let tyrants shake their iron rod, and slavery clank her galling chains. We fear them not, we trust in God, New England's God forever reigns. The foe comes on with haughty stride. Our troops advance with martial noise. Their veterans flee before our youth, and generals yield to beardless boys.

- William Billings, "Chester" (1770), The New England Psalm Singer (1770).

- Among the Natural Rights of the Colonists are these First a Right to Life; Secondly to Liberty; thirdly to Property; together with the Right to support and defend them in the best manner they can—Those are evident Branches of, rather than deductions from the Duty of Self Preservation, commonly called the first Law of Nature— All Men have a Right to remain in a State of Nature as long as they please: And in case of intollerable Oppression, Civil or Religious, to leave the Society they belong to, and enter into another. — When Men enter into Society, it is by voluntary consent; and they have a right to demand and insist upon the performance of such conditions, And previous limitations as form an equitable original compact.— Every natural Right not expressly given up or from the nature of a Social Compact necessarily ceded remains. — All positive and civil laws, should conform as far as possible, to the Law of natural reason and equity.

- Town of Boston, The Rights of the Colonists (20 November 1772), Boston.

- To show the world that we are not influenced by any contracted or interested motives, but a general philanthropy for all mankind, of whatever climate, language, or complexion, we hereby declare our disapprobation and abhorrence of the unnatural practice of slavery in America, however the uncultivated state of our country, or other specious arguments may plead for it, a practice founded in injustice and cruelty, and highly dangerous to our liberties, as well as our lives, debasing part of our fellow-creatures below men, and corrupting the virtue and morals of the rest; and is laying the basis of that liberty we contend for, and which we pray the Almighty to continue to the latest posterity, upon a very wrong foundation. We therefore resolve, at all times to use our utmost endeavors for the manumission of slaves.

- Darien Committee, Darien Resolutions (12 January 1775), Georgia, as quoted in American Archives, Vol I., p. 1,136.

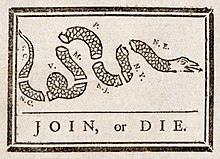

- Join, or Die.

- Benjamin Franklin, in a political cartoon first published in The Pennsylvania Gazette (9 May 1754), initially regarding the situations at the start of the French and Indian War, it was later re-used during the American rebellion against Great Britain.

- I will not, I cannot justify it... I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be offered to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we do is to improve it, if it happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot and an abhorrence of slavery.

- Patrick Henry, as quoted in letter to Robert Pleasants (18 January 1773).

- The colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black... Does it follow that tis right to enslave a man because he is black? Will short curl’d hair like wool, of christian hair, as tis called by those, hearts are as hard as the nether millstone, help the argument? Can any logical inference in favour of slavery, be drawn from a flat nose, a long or a short face... Are not women born as free as men? Would it not be infamous to assert that the ladies are all slaves by nature?

- I need say hardly anything in favor of the Intellects of the Negroes, or of their capacities for virtue and happiness, although these have been supposed by some to be inferior to those of the inhabitants of Europe. The accounts which travelers give of their ingenuity, humanity and strong attachments to their parents, relations, friends and country, show us that they are equal to the Europeans... All the vices which are charged upon the Negroes in the southern colonies, and the West Indies, such as Idleness, Treachery, Theft and the like, are the genuine offspring of slavery, and serve as an argument to prove, that they were not intended, by Providence, for it.

- Benjamin Rush, "On Slavekeeping" (1773).

- All Men being naturally equal, as descended from a common Parent, enbued with like Faculties and Propensities, having originally equal Rights and Properties, the Earth being given to the Children of Men in general, without any difference, distinction, natural Preheminence, or Dominion of one over another, yet Men not being equally industrious and frugal, their Properties and Enjoyments would be unequal.

- Abraham Williams, An Election Sermon (1762).

- For the most trifling reasons, and sometimes for no conceivable reason at all, his majesty has rejected laws of the most salutary tendency. The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the infranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa. Yet our repeated attempts to effect this by prohibitions, and by imposing duties which might amount to a prohibition, have been hitherto defeated by his majesty's negative: thus preferring the immediate advantages of a few British corsairs to the lasting interests of the American states, and to the rights of human nature deeply wounded by this infamous practice.

- The colonists were struggling not only against the armies of a great nation, but against the settled opinions of mankind; for the world did not then believe that the supreme authority of government could be safely intrusted to the guardianship of the people themselves.

- James A. Garfield, inaugural address (4 March 1881)

- It is not here necessary to examine in detail the causes which led to the American Revolution. In their immediate occasion they were largely economic. The colonists objected to the navigation laws which interfered with their trade, they denied the power of Parliament to impose taxes which they were obliged to pay, and they therefore resisted the royal governors and the royal forces which were sent to secure obedience to these laws. But the conviction is inescapable that a new civilization had come, a new spirit had arisen on this side of the Atlantic more advanced and more developed in its regard for the rights of the individual than that which characterized the Old World. Life in a new and open country had aspirations which could not be realized in any subordinate position. A separate establishment was ultimately inevitable. It had been decreed by the very laws of human nature. Man everywhere has an unconquerable desire to be the master of his own destiny.

- Republicanism was the ideology of the American Revolution, and as such it became the source of much of what we Americans still believe, the source of many of our noblest ideals and most persistent values. Indeed, republicanism is today so much taken for granted that it is difficult for us to appreciate its once revolutionary character. We live in a world in which almost all states purport to be republican; even those few states such as Britain or Sweden that remain monarchies are more republican in fact than some others that claim to be in theory. But in the eighteenth century most governments were monarchies, and republicanism was their enemy.

- Gordon S. Wood, "Classical Republicanism and the American Revolution" (April 1990), Chicago-Kent Law Review.

Boston Massacre (1770)

[edit]

- I have the most animating confidence that the present noble struggle for liberty will terminate gloriously for America.

- The country shall be independent, and we will be satisfied with nothing short of it.

- Samuel Adams, remark in "small confidential companies"; in William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment, of the Independence of the United States of America, vol. 1 (1788, reprinted 1969), entry for March 9, 1774, p. 347.

- The first victim of the Boston Massacre, on the 5th of March 1770, which made the fires of resistance burn more intensely, was a colored man. Hundreds of colored men entered the ranks and fought bravely on all the fields of the Revolution.

- Henry Wilson, speech (22 June 1853).

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Concord Hymn" (1837), commemorating the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

The Battle of Bunker Hill (June 1775)

[edit]- Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes.

- Instructions of Colonel William Prescott to American troops before the Battle of Bunker Hill.

- We... sustained the enemy's attacks with great bravery... and after bearing, for about 2 hours, as severe and heavy a fire as perhaps was ever known, and many having fired away all their ammunition... we were overpowered by numbers and obliged to leave.

- Corporal Amos Farnsworth, Massachusetts Militia, describing the Battle of Bunker Hill.

- A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.

- British General Henry Clinton, remarking on the battle in his diary; although the British won the battle, they suffered a substantial loss of British troops.

Other actions in 1775

[edit]

- If it was possible for men who exercise their reason, to believe that the divine Author of our existence intended a part of the human race to hold an absolute property in, and an unbounded power over others, marked out by his infinite goodness and wisdom, as the objects of a legal domination never rightfully resistible, however severe and oppressive, the inhabitants of these Colonies might at least require from the Parliament of Great Britain some evidence, that this dreadful authority over them has been granted to that body. But a reverence for our great Creator, principles of humanity, and the dictates of common sense, must convince all those who reflect upon the subject, that Government was instituted to promote the welfare of mankind, and ought to be administered for the attainment of that end.

- If ye love wealth better than liberty, the tranquility of servitude than the animating contest of freedom, go from us in peace. We ask not your counsels or arms. Crouch down and lick the hands which feed you. May your chains sit lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen.

- Samuel Adams, speech at the Philadelphia State House (1 August 1775)

- Come out, you old rat. [Surrender] in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress.

- Ethan Allen, leader of the Green Mountain Boys, demanding the surrender of the British commander of Fort Ticonderoga.

- When the unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy.

- King George III, Address to Parliament (27 October 1775).

- Connecticut wants no Massachusetts men in her corps.... Massachusetts thinks there is no necessity for a Rhode Islander to be introduced into her [units].

- Gen. George Washington, commanding the Continental Army outside Boston, on the localism of the colonial units.

- Proceed, great chief, with

virtue on thy side.

Thy ev’ry action let the

goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and

a throne tat shine,

With gold unfading,

Washington! be thine.- Boston slave poet Phyllis Wheatley.

- Could I have foreseen what I have, and am like to experience, no consideration upon earth should have induced me to accept this command.

- Gen. George Washington, reflecting on his frustrations coming from both Congress and the states in commanding the Continental Army.

- A navy is essentially and necessarily aristocratic. True as may be the political principles for which we are now contending they can never be practically applied or even admitted on board ship, out of port, or off soundings. This may seem a hardship, but it is nevertheless the simplest of truths. Whilst the ships sent forth by the Congress may and must fight for the principles of human rights and republican freedom, the ships themselves must be ruled and commanded at sea under a system of absolute despotism.

- John Paul Jones, letter to the Naval Committee of Congress (14 September 1775).

- There was not in all the colonial legislation of America one single law which recognized the rightfulness of slavery in the abstract; that in 1774 Virginia stigmatized the slave-trade as 'wicked, cruel, and unnatural'; that in the same year Congress protested against it 'under the sacred ties of virtue, honor, and love of country'; that in 1775 the same Congress denied that God intended one man to own another as a slave; that the new Discipline of the Methodist Church, in 1784, and the Pastoral Letter of the Presbyterian Church, in 1788, denounced slavery; that abolition societies existed in slave States, and that it was hardly the interest even of the cotton-growing States, where it took a slave a day to clean a pound of cotton, to uphold the system... Jefferson, in his address to the Virginia Legislature of 1774, says that 'the abolition of domestic slavery is the greatest object of desire in these colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state'; and while he constantly remembers to remind us that the Jeffersonian prohibition of slavery in the territories was lost in 1784, he forgets to add that it was lost, not by a majority of votes — for there were sixteen in its favor to seven against it — but because the sixteen votes did not represent two thirds of the States; and he also incessantly forgets to tell us that this Jeffersonian prohibition was restored by the Congress of 1785, and erected into the famous Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which was re-enacted by the first Congress of the United States and approved by the first President.

- George William Curtis, "The Present Aspect of the Slavery Question" (18 October 1859), New York City.

- We have counted the cost of this contest and find nothing so dreadful as voluntary slavery. Honor, justice, and humanity forbid us to tamely surrender that freedom which we received from our gallant ancestors, and which our innocent posterity have a right to receive from us.... Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great; and, if necessary, foreign assistance is undoubtedly attainable.

- Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson, Continental Congress Declaration on the Necessity of Taking up Arms (1775).

The American Revolution becomes the War of Independence

[edit]

- If we separate from Britain, what code of laws will be established? How shall we be governed so as to retain our liberties? Can any government be free which is not administered by general stated laws? Who shall frame these laws? Who will give them force and energy?

- Abigail Adams (wife of John Adams) (1775)

- Objects of the most Stupendous Magnitude, Measures in which the Lives and Liberties of Millions, born and unborn are most essentially interested, are now before Us. We are in the very midst of a Revolution, the most compleat, unexpected, and remarkable of any in the History of Nations. A few Matters must be dispatched before I can return. Every Colony must be induced to institute a perfect Government. All the Colonies must confederate together, in some solemn Compact. The Colonies must be declared free and independent states, and Embassadors, must be Sent abroad to foreign Courts, to solicit their Acknowledgment of Us, as Sovereign States, and to form with them, at least with some of them commercial Treaties of Friendship and Alliance. When these Things shall be once well finished, or in a Way of being so, I shall think that I have answered the End of my Creation, and sing with Pleasure my Nunc Dimittes, or if it should be the Will of Heaven that I should live a little longer, return to my Farm and Family, ride Circuits, plead Law, or judge Causes, just as you please.

- John Adams, letter to William Cushing (9 June 1776)

- God save our American states!

- Anonymous, as quoted in letter to Abigail Adams (21 July 1776), by John Adams

- I am determined to defend my rights and maintain my freedom or sell my life in the attempt.

- Nathanael Greene, as quoted in Conflict of conviction: a reappraisal of Quaker involvement in the American Revolution (1990), by William C. Kashatus, p. 45

- When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

- Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence of the United States of America (4 July 1776).

- The reference to "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God" appears to be borrowed from Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, epistle iv, line 331: "Slave to no sect, who takes no private road, But looks through Nature up to Nature’s God"; Pope, in turn, may have borrowed it from a letter to Pope by Henry, Viscount Bolingbroke St. John, who praised the modesty of "[o]ne follows Nature and Nature's God; that is, he follows God in his works and in his word".

- We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

- He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

- We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America, in general Congress, assembled, do, in the name, and by authority of the good people of these colonies, solemnly publish and declare, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.

- We must all hang together now, or assuredly we shall hang separately.

- Benjamin Franklin (1776), on the need for the Americans to fight together for independence.

- [N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support and religious worship, place, or ministry... nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion on matters of religion.

- Thomas Jefferson, Virginia Bill on Religious Freedom (1776)

- We have large armies, well disciplined and appointed, with commanders inferior to none in military skill, and superior in activity and zeal. We are furnished with arsenals and stores beyond our most sanguine expectations... Our union is now complete; our constitution composed, established, and approved. You are now the guardians of your own liberties. We may justly address you, as the decemviri did the Romans, and say, 'Nothing that we propose can pass into a law without your consent. Be yourselves, O Americans, the authors of those laws on which your happiness depends.'

- Samuel Adams, speech about the Declaration of Independence (1 August 1776)

- You have now in the field armies sufficient to repel the whole force of your enemies and their base and mercenary auxiliaries. The hearts of your soldiers beat high with the spirit of freedom; they are animated with the justice of their cause, and while they grasp their swords can look up to Heaven for assistance. Your adversaries are composed of wretches who laugh at the rights of humanity, who turn religion into derision, and would, for higher wages, direct their swords against their leaders or their country. Go on, then, in your generous enterprise, with gratitude to Heaven for past, success, and confidence of it in the future. For my own part, I ask no greater blessing than to share with you the common danger and common glory. If I have a wish dearer to my soul than that my ashes may be mingled with those of a Warren and a Montgomery, it is that these American States may never cease to be free and independent.

- Samuel Adams, speech about the Declaration of Independence (1 August 1776)

- [T]he free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be allowed, within this State.

- New York State Constitution of 1777 (1777).

- The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind are affected, and in the Event of which, their Affections are interested. The laying a Country desolate with Fire and Sword, declaring War against the natural rights of all Mankind, and extirpating the Defenders thereof from the Face of the Earth, is the Concern of every Man to whom Nature hath given the Power of feeling; of which Class, regardless of Party Censure, is the AUTHOR.

- Thomas Paine, in Common Sense (1776).

- O! ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the Old World is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

- Thomas Paine, in Common Sense (1776). First published 10 January 1776, the most commonly reproduced edition is the third, published on 14 February 1776. Full text online.

- I challenge the warmest advocate of reconciliation, to show a single advantage that this continent can reap, by being connected with Great Britain. I repeat the challenge, not a single advantage is derived. Our corn will fetch its price in any market in Europe, and our imported goods must be paid for, buy them where we will.

But the injuries and disadvantages we sustain by that connection, are without number; and our duty to mankind at large, as well as to ourselves, instruct us to renounce the alliance: Because, any submission to, or dependence on Great Britain, tends directly to involve this continent in European wars and quarrels; and sets us at variance with nations, who would otherwise seek our friendship, and against whom, we have neither anger nor complaint. As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it. It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions.

Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain....

It is repugnant to reason and the universal order of things... to suppose that this continent can longer remain subject to any external power.... Freedom has been haunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger, and England has given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind....

The period of debate is closed. Arms, as the last resource, must decide the contest...

Everything that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, 'TIS TIME TO PART.- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (1776)

- That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot by any compact deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

- Not a place upon earth might be so happy as America. Her situation is remote from all the wrangling world, and she has nothing to do but to trade with them. A man can distinguish himself between temper and principle, and I am as confident, as I am that God governs the world, that America will never be happy till she gets clear of foreign dominion. Wars, without ceasing, will break out till that period arrives, and the continent must in the end be conqueror; for though the flame of liberty may sometimes cease to shine, the coal can never expire.

- Thomas Paine, The Crisis No. I (23 December 1776)

- It is the object only of war that makes it honorable. And if there was ever a just war since the world began, it is this in which America is now engaged... We fight not to enslave, but to set a country free, and to make room upon the earth for honest men to live in.

- Thomas Paine, The Crisis No. IV (12 September 1777). Quotes reported in Hoyt's New Cyclopedia Of Practical Quotations (1922), pp. 841-60

- [W]ith respect to our rights, and the acts of the British government contravening those rights, there was but one opinion on this side of the water. All American whigs thought alike on these subjects. When forced, therefore, to resort to arms for redress, an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right.

- Thomas Jefferson, letter to Henry Lee (8 May 1825)

- [In December 1777] General Washington was crossing the Schuylkill, about the time the British left Philadelphia, when one Isaac Tyson told me that the American army was pressing all the horses and wagons they could find... I told my Master, who was a Quaker, of it. He said, "Does thee not wish that they would come and press my horses and wagon and press thee to drive it?" I told him I did. I had a whip in my hand which he took from me and gave me several lashes with it and said, "Thee Scotch rebel, thou was a rebel in thine own country, and now thou has come here to rebel." So I was determined to leave him, which I did in about a week from the time he struck me, and then I enlisted in Colonel Preston's artillery.

- Daniel Morris (b. 1756), narrative written in 1846, quoted in The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, ed. John C. Dann (1999), pp. 163-164

- The Declaration of Independence includes ALL men, black as well as white, and forth...

- Abraham Lincoln, speech at Springfield, Illinois (26 June 1857)

- All honor to Jefferson to the man, who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a mere revolutionary an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all time, and so to embalm it there to-day and in all coming days it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling block to the very harbingers of reappearing tyranny and oppression.

- Abraham Lincoln, Letter to H.L. Pierce and others (Springfield, Illinois, April 6, 1859), published in Essential American History: Abraham Lincoln - The Complete Papers and Writings, Biographically Annotated, The Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln © 2012, Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck, 86450 Münster, Germany, ISBN: 97838496200103

- The Declaration of Independence was the passionate manifesto of a revolutionary war, and its doctrine of equal human rights a glittering generality... It would have been perfectly easy to say, 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all white men of the European race upon this continent are created equal — to their brethren across the water; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; but that yellow, blacky brown, and red men have no such rights'. It would have been very easy to say this. Our fathers did not say it, because they did not mean it. They were men who meant what they said, and who said what they meant, and meaning all men, they said all men. They were patriots asserting a principle and ready to die for it, not politicians pettifogging for the presidency.

- George William Curtis, "The Present Aspect of the Slavery Question" (18 October 1859), New York City

- When this nation was in trouble, in its early struggles, it looked upon the Negro as a citizen. In 1776 he was a citizen. At the time of the formation of the Constitution the Negro had the right to vote in eleven States out of the old thirteen. In your trouble you have made us citizens. In 1812 General Jackson addressed us as citizens; 'fellow-citizens'. He wanted us to fight. We were citizens then! And now, when you come to frame a conscription bill, the Negro is a citizen again. He has been a citizen just three times in the history of this government, and it has always been in time of trouble. In time of trouble we are citizens. Shall we be citizens in war, and aliens in peace? Would that be just?

- Frederick Douglass, "What the Black Man Wants", speech in Boston, Massachusetts (1865)

Military Operations in the Middle States: 1776–1777

[edit]

- When once these rebels have felt a smart blow, they will submit.

- Comment of German mercenary soldier from Hesse, before going into battle against American rebels (1776).

- I am worried to death. I think the game is pretty near up.

- Gen. George Washington, in a letter to his brother, after his Continental Army was driven by the British from New York, across New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania (1776).

- It was as severe a night as ever I saw, and after two battalions had landed, the storm increased so much, and the river was so full of ice, that it was impossible to get the artillery over.

- Thomas Rodney, a Continental soldier, describing the crossing of the Delaware River leading to the surprise attack and victory at Trenton, New Jersey (December 25–26, 1776).

- [He] had lost all his clothes. He was in an old, dirty blanket jacket, his beard long, and his face so full of sores he could not clean it.

- Artist Charles Wilson Peale, seeing his brother participating in Washington's army crossing the Delaware River in its counterattack on the British (December 1776).

The Fighting in 1777–1781

[edit]

- Britain has been moving earth and hell to obtain allies against us, yet it is improper in us to propose an alliance! Great Britain has borrowed all the superfluous wealth of Europe, in Italy, Germany, Holland, Switzerland, and some in France, to murder us, yet it is dishonorable in us to propose to borrow money! By heaven, I would make a bargain with all Europe, if it lay with me. Let all Europe stand still, neither lend men nor money nor ships to England nor America, and let them fight it out alone. I would give my share of millions for such a bargain. America is treated unfairly and ungenerously by Europe. But thus it is, mankind will be servile to tyrannical masters, and basely devoted to vile idols.

- John Adams, letter to B. Franklin (16 April 1781), Leyden.

- We shall divert through our own Country a branch of commerce which the European States have thought worthy of the most important struggles and sacrifices, and in the event of peace... we shall form to the American union a barrier against the dangerous extension of the British Province of Canada and add to the Empire of liberty an extensive and fertile Country thereby converting dangerous Enemies into valuable friends.

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to George Rogers Clark (25 December 1780).

- On the whole, I have annoyances to bear, of which you can hardly form a conception. One of them is the mutual jealousy of almost all the French officers, particularly against those of higher rank than the rest. These people think of nothing but their incessant intrigues and backbitings. They hate each other like the bitterest enemies, and endeavor to injure each other wherever an opportunity offers. I have given up their society, and very seldom see them. La Fayette is the sole exception; I always meet him with the same cordiality and the same pleasure. He is an excellent young man, and we are good friends... La Fayette is much liked, he is on the best of terms with Washington.

- Johann de Kalb, letter to Madame de Kalb (5 January 1778), as quoted in The Marquis de La Fayette in the American Revolution (1894), by Charlemagne Tower. J.B. Lippincott Company, p. 241.

- No! No! Gentlemen, no emotion for me. But, those of congratulation. I am happy. To die is the irreversible decree of him who made us. Then what joy to be able to meet death without dismay. This, thank God, is my case. The happiness of man is my wish, that happiness I deem inconsistent with slavery, and to avert so great an evil from an innocent people, I will gladly meet the British tomorrow, at any odds whatever... It is with equal regret, my dear sirs, that I part with you. Because I feel a presentiment that we part to meet no more... Oh, no! It is impossible. War is a kind of game, and has its fixed rules, whereby, when we are well acquainted with them, we can pretty correctly tell how the trial will go. Tomorrow it seems, the die is to be cast, and, in my judgement, without the least chance on our side. The militia will, I suppose as usual, play the back game. That is, get out of battle as fast as their legs will carry them. But that, you know, won't do for me. I am an old soldier, and cannot run, and I believe I have some brave fellows that will stand by me to the last. So, when you hear of our battle, you will probably hear that your old friend, De Kalb, is at rest... Well, sir. Perhaps a few hours will show who are the brave.

- Johann de Kalb, to a British military officer (August 1780), as quoted in Washington and the Generals of the American Revolution (1856), by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, William Gilmore Simms, and Edward Duncan Ingraham. J.B. Lippincott, p. 271. Also quoted in "Death of Baron De Kalb" (1849), by Benjamin Franklin Ells, The Western Miscellany, Volume 1, pp. 233–234.

- I thank you sir for your generous sympathy, but I die the death I always prayed for, the death of a soldier fighting for the rights of man.

- Johann de Kalb, to a British military officer (August 1780), as quoted in Washington and the Generals of the American Revolution (1856), by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, William Gilmore Simms, and Edward Duncan Ingraham. J.B. Lippincott, p. 271. Also quoted in "Death of Baron De Kalb" (1849), by Benjamin Franklin Ells, The Western Miscellany, Volume 1, p. 234. These were reportedly his last words.

- Would it not be as well to liberate and make soldiers at once of the blacks themselves, as to make them instruments for enlisting white soldiers? It would certainly be more consonant to the principles of liberty which ought never to be lost sight of in a contest for liberty...

- James Madison, as quoted in letter to Joseph Jones (28 November 1780).

- These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered.

- Thomas Paine, in his essay, The Crisis (1777).

- Good God, gentlemen! Our cause is ruined if you engage men for only a year. You must not think of it. If we ever hope for success, we must have men enlisted for the whole term of the war.

- General Washington, urging Congress to establish a long-term Continental Army (1777).

- The unfortunate soldiers were in want of everything; they had neither coats, nor hats, nor shirts, nor shoes; their feet and their legs froze till they grew black and it was often necessary to amputate them.... The army frequently passed whole days without food.

- Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, observing the Continental Army at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, after his arrival from France (1777).

- Our citizenship in the United States is our national character. Our citizenship in any particular state is only our local distinction. By the latter we are known at home, by the former to the world. Our great title is AMERICANS.

- Thomas Paine, as quoted in The Crisis No. XIII (April 1783).

- Poor food — hard lodging — cold weather — fatigue — nasty clothes — nasty cookery.... There comes a bowl of beef soup, full of burnt leaves and dirt!

- Continental Army surgeon Albigence Waldo, writing in his diary on conditions of the army at Valley Forge (1777).

- France is... what they call the dominant power of Europe, being incomparably the most powerful at land, that united in a close alliance with our states, and enjoying the benefit of our trade, there is not the smallest reason to doubt but both will be a sufficient curb upon the naval power of Great Britain.

- John Adams to Sam Adams, explaining the alliance between the United States and France (1778).

- In June 1781, the French and American armies joined forces at White Plains. Baron Closen, a German officer in the French Royal Deux-Ponts, estimated the American army to be about one fourth black, about 1,200 --1,500 men out of less than 6,000 Continentals! On the eve of its decisive victory over Lord Cornwallis, the Continental Army had reached a degree of integration it would not achieve again for another 200 years. Among the troops at White Plains was the Rhode Island Regiment, the two battalions had been consolidated on 1 January 1781, with its high percentage of African-Americans, which Closen considered the best American unit: 'the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in its maneuvres'.

- Robert A. Selig, "The Revolution's Black Soldiers", American Revolution.

- The Continental Army exhibited a degree of integration not reached by the American army again for 200 years, until after World War II.

- Mary V. Thompson, "The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret", Mount Vernon.

The War at Sea

[edit]- I have not yet begun to fight!

- The famous response of John Paul Jones, in the early phase of the Battle of Flamborough Head, (23 September 1779) to an inquiry by his opponent (Captain Richard Pearson of the Royal Navy ship HMS Serapis) as to whether he was surrendering his ship, the USS Bonhomme Richard in reply to the British ship Serapis, as recounted in the reminiscences of Jones's First Lieutenant, Richard Dale, as published in The Life and Character of John Paul Jones, a Captain in the United States Navy (1825) by John Henry Sherburne:

- ...the Bon Homme Richard, having head way, ran her bows into the stern of the Serapis. We had remained in this situation but a few minutes when we were again hailed by the Serapis, "Has your ship struck?" To which Captain Jones answered, "I have not yet begun to fight!" In Naval teminology to "strike the colours" means to haul down the ship's flag to signify surrender, but here the use of the ship as subject of the sentence may imply a pun on the non-naval use of "struck".

- The exact wording of his reply is uncertain, and several accounts exist. The standard version above is from an account of the engagement by one of Jones's officers, First Lieutenant Richard Dale. John Henry Sherburne, The Life and Character of John Paul Jones, 2d ed. (1851), p. 121. Sherburne includes Jones's letter of October 3, 1779, to Benjamin Franklin, where he says, p. 116, "The English commodore asked me if I demanded quarters, and I having answered him in the most determined negative, they renewed the battle with double fury". Benjamin Rush writes, "I heard a minute account of his engagement with the Seraphis in a small circle of gentlemen at a dinner. It was delivered with great apparent modesty and commanded the most respectful attention. Towards the close of the battle, while his deck was swimming in blood, the captain of the Seraphis called him to strike. 'No, Sir,' said he, 'I will not, we have had but a small fight as yet.'" George W. Corner, ed., The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush (1948), p. 157.

The War in the South

[edit]

- Colonel [John]Laurens... is on the way to South Carolina... to raise two three or four battalions of negroes... by contributions form owners in proportion to the number they possess...

I have not the least doubt, that the negroes will make excellent soldiers, with proper management....

I foresee that his project will have to combat much opposition from prejudice and self-interest. The contempt we have been taught to entertain for the blacks, makes us fancy many things that are founded neither in reason nor experience....

An essential part of the plan is to give them their freedom with their muskets. This will secure their fidelity, animate their courage, and I believe will have a good influence upon those who remain, by opening a door to their emancipation.- Col. Alexander Hamilton, aide to Gen. George Washington (1779).

- We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.

- Gen. Nathanael Greene of Rhode Island, Continental Army commander in the South, describing guerrilla warfare against the British (1781).

- Their number did not exceed 20 men and boys, some white, some black, and all mounted, but most of them miserably equipped.

- American cavalry raiders in South Carolina commanded by Francis Marion ("the Swamp Fox") as described by an officer on the staff of Gen. Horatio Gates, commanding American forces in the South (1780).

- I have the mortification to inform your Excellency that I have been forced to... surrender the troops under my command.

- Gen. Cornwallis, commanding British forces in the South, informing the commander of all British forces in North America, Gen. Clinton, that he surrendered his army at Yorktown, Virginia (October 19, 1781).

- This is a most glorious day.

- An American doctor, upon learning that Gen. Cornwallis, surrendered his army at Yorktown (1781).

The End of the War

[edit]

- There was as much sorrow as joy.... We had lived together as a family of brothers for several years, setting aside some little family squabbles, like most other families, had shared with each other the hardships, dangers, and sufferings incident to a soldier’s life, had sympathized with each other in trouble and in sickness; had assisted in bearing each other’s burdens.... And now we were to be... parted forever.

- Joseph Plumb Martin, a soldier in the Continental Army, on the disbanding of the army, in his memoir, Private Yankee Doodle (published 1830).

- Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed.... We were then about to part form the man who had conducted through a long and bloody war, and under whose conduct the glory and independence of our country has been achieved.

- Benjamin Tallmadge, remembering the scene at Fraunces Tavern, New York City, as General Washington said farewell to his officers and left the Continental Army at the end of the War of Independence (1783).

Aftermath

[edit]

- Neither my father or mother, grandfather or grandmother, great grandfather or great grandmother, nor any other relation that I know of, or care a farthing for, has been in England these one hundred and fifty years; so that you see I have not one drop of blood in my veins but what is American.

- John Adams, to a foreign ambassador (1785), as quoted in The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: Autobiography (1851), by Charles F. Adams, p. 392.

- But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations.

- John Adams, letter to Hezekiah Niles (13 February 1818)

- They are escaped convicts. His Majesty is fortunate to be rid of such rabble. Their true God is power.

- Oliver Sharpin, The American Rebels (1804).

- You say that at the time of the Congress, in 1765, "The great mass of the people were zealous in the cause of America". "The great mass of the people" is an expression that deserves analysis. New York and Pennsylvania were so nearly divided, if their propensity was not against us, that if New England on one side and Virginia on the other had not kept them in awe, they would have joined the British. Marshall, in his life of Washington, tells us, that the southern States were nearly equally divided. Look into the Journals of Congress, and you will see how seditious, how near rebellion were several counties of New York, and how much trouble we had to compose them. The last contest, in the town of Boston, in 1775, between whig and tory, was decided by five against two. Upon the whole, if we allow two thirds of the people to have been with us in the revolution, is not the allowance ample? Are not two thirds of the nation now with the administration? Divided we ever have been, and ever must be. Two thirds always had and will have more difficulty to struggle with the one third than with all our foreign enemies.

- John Adams, letter to Thomas McKean (31 August 1813); in Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams (1856), vol. 10, p. 63. He referred to a Congress "held at New York, A.D. 1765, on the subject of the American stamp act" (p. 62).

- Every measure of prudence, therefore, ought to be assumed for the eventual total extirpation of slavery...

- John Adams, letter to Robert J. Evans (8 June 1819).

- I have, through my whole life, held the practice of slavery in such abhorrence...

- John Adams, as quoted in letter to Robert J. Evans (8 June 1819).

- The prevailing Notion now is to Continue the most abject State of Slavery in this Common-Wealth...

- Robert Carter III, letter to James Manning (1786).

- Let it never be forgotten that the cause of the United States is the cause of human nature.

- If it is worth a bloody struggle to establish this nation, it is worth one to preserve it.

- Oliver P. Morton, speech (22 November 1860), as quoted in Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850–1880: History of Indiana III (1995), by Emma Lou Thornbrough. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, p. 102.

- To grant suffrage to the black man in this country is not innovation, but restoration. It is a return to the ancient principles and practices of the Fathers.

- James A. Garfield, oration delivered at Ravenna, Ohio (4 July 1865).

- During the war of the Revolution, and in 1788, the date of the adoption of our national Constitution, there was but one State among the thirteen whose constitution refused the right of suffrage to the negro. That State was South Carolina. Some, it is true, established a property qualification; all made freedom a prerequisite; but none save South Carolina made color a condition of suffrage. The Federal Constitution makes no such distinction, nor did the Articles of Confederation. In the Congress of the Confederation, on the 25th of June, 1778, the fourth article was under discussion. It provided that 'the free inhabitants of each of these States — paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted — shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States.' The delegates from South Carolina moved to insert between the words 'free inhabitants' the word 'white', thus denying the privileges and immunities of citizenship to the colored man. According to the rules of the convention, each State had but one vote. Eleven States voted on the question. One was divided; two voted aye; and eight voted no. It was thus early, and almost unanimously, decided that freedom, not color, should be the test of citizenship. No federal legislation prior to 1812 placed any restriction on the right of suffrage in consequence of the color of the citizen. From 1789 to 1812 Congress passed ten separate laws establishing new Territories. In all these, freedom, and not color, was the basis of suffrage.

- James A. Garfield, oration delivered at Ravenna, Ohio (4 July 1865).

- The spirit of liberty that had been so invigorated by the events of the 1770s did manifest itself in a number of important measures affecting the status of America's slaves. In 1777 the constitution for the new state of Vermont completely abolished slavery, and Massachusetts soon followed suit. Many other Northern states, such as Pennsylvania in 1780, adopted legislation aimed at gradual emancipation during this period, although it was not until 1804 that New Jersey finally enacted a similar law. Not surprisingly, in the South anti-slavery gains were much more modest. But three Southern states, including Virginia in 1782, passed laws that made it possible for owners to manumit their slaves. It was the provisions of this law that Washington had to respect in formulating the manumission plan outlined in his will.

- "George Washington: His Troubles With Slavery" (12 June 2006), HistoryNet.

- As long as offices are open to all men and no constitutional rank is established, it is pure republicanism.

- The laws of certain states …give an ownership in the service of negroes as personal property…. But being men, by the laws of God and nature, they were capable of acquiring liberty—and when the captor in war …thought fit to give them liberty, the gift was not only valid, but irrevocable.

- Alexander Hamilton, Philo Camillus no. 2 (1795), as quoted in Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961-), 19:101-2.

- That men should pray and fight for their own freedom, and yet keep others in slavery, is certainly acting a very inconsistent, as well as unjust and, perhaps, impious part, but the history of mankind is filled with instances of human improprieties.

- John Jay, Letter to Reverend Doctor Price (27 September 1785).

- It is much to be wished that slavery may be abolished. The honour of the States, as well as justice and humanity, in my opinion, loudly call upon them to emancipate these unhappy people. To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused.

- John Jay, Letter to R. Lushington (15 March 1786).

- Our people had been so long accustomed to the practice and convenience of having slaves, that very few among them even doubted the propriety and rectitude of it. Some liberal and conscientious men had indeed, by their conduct and writings, drawn the lawfulness of slavery into question.

- John Jay, as quoted in letter to the President of the English Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves (June 1788).

- A British vessel, stopping on the way back from India at the Comoro Islands in the Mozambique Channel, finds the native inhabitants in revolt against their Arab masters; and when they ask why they have taken arms, are told: "America is free, could not we be?"

- Gijsbert Karel, Count van Hogendorp, in 1784, quoted in "The age of the democratic revolution: a political history of Europe and America, 1760-1860" by Robert Roswell Palmer (1969).

- Chief Justice does not directly assert, but plainly assumes, as a fact, that the public estimate of the black man is more favorable now than it was in the days of the Revolution. This assumption is a mistake... In those days, as I understand, masters could, at their own pleasure, emancipate their slaves; but since then, such legal restraints have been made upon emancipation, as to amount almost to prohibition. In those days, Legislatures held the unquestioned power to abolish slavery in their respective States; but now it is becoming quite fashionable for State Constitutions to withhold that power from the Legislatures. In those days, by common consent, the spread of the black man's bondage to new countries was prohibited; but now, Congress decides that it will not continue the prohibition, and the Supreme Court decides that it could not if it would. In those days, our Declaration of Independence was held sacred by all, and thought to include all; but now, to aid in making the bondage of the negro universal and eternal, it is assailed, and sneered at, and construed, and hawked at, and torn, till, if its framers could rise from their graves, they could not at all recognize it.

- Abraham Lincoln, speech at Springfield, Illinois (26 June 1857).

- Now, my countrymen if you have been taught doctrines conflicting with the great landmarks of the Declaration of Independence; if you have listened to suggestions which would take away from its grandeur, and mutilate the fair symmetry of its proportions; if you have been inclined to believe that all men are not created equal in those inalienable rights enumerated by our chart of liberty, let me entreat you to come back. Return to the fountain whose waters spring close by the blood of the Revolution. Think nothing of me, take no thought for the political fate of any man whomsoever; but come back to the truths that are in the Declaration of Independence. You may do anything with me you choose, if you will but heed these sacred principles. You may not only defeat me for the Senate, but you may take me and put me to death. While pretending no indifference to earthly honors, I do claim to be actuated in this contest by something higher than an anxiety for office. I charge you to drop every paltry and insignificant thought for any man's success. It is nothing; I am nothing; Judge Douglas is nothing. But do not destroy that immortal emblem of Humanity; the Declaration of American Independence.

- Abraham Lincoln, speech at Lewistown, Illinois (17 August 1858).

- We have seen the mere distinction of color made, in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.

- James Madison, speech at the Constitutional Convention (6 June 1787).

- It has been said that America is a country for the poor, not for the rich. There would be more correctness in saying it is the country for both, where the latter have a relish for free government; but, proportionally, more for the former than for the latter.

- What was the origin of our slave population? The evil commenced when we were in our Colonial state, but acts were passed by our Colonial Legislature, prohibiting the importation, of more slaves, into the Colony. These were rejected by the Crown. We declared our independence, and the prohibition of a further importation was among the first acts of state sovereignty. Virginia was the first state which instructed her delegates to declare the colonies independent. She braved all dangers. From Quebec to Boston, and from Boston to Savannah, Virginia shed the blood of her sons. No imputation then can be cast upon her in this matter. She did all that was in her power to do, to prevent the extension of slavery, and to mitigate its evils.

- James Monroe, speech in the Virginia State Convention for altering the Constitution (2 November 1829).

- Madison, like many of the other Founders, was acutely aware of the injustice of slavery and saw it as one form of the oppression that their innovative approach to government as to eliminate.

- Tom Palmer, Realizing Freedom: Libertarian Theory, History, and Practice (2009), p. 338.

- The glorious and ever memorable Revolution can be justified on no other principles but what doth plead with greater force for the emancipation of our slaves, in proportion as the oppression exercised over them exceeds the oppression formerly exercised by Great Britain over these states.

- Petition from Frederick County (1784), Virginia.

- Even though the state had slaves, the Founders proclaimed all men had equal rights.

- Erik S. Root, All Honor to Jefferson, p. 90.

- The American war is over; but this far from being the case with the American revolution. On the contrary, nothing but the first act of the drama is closed. It remains yet to establish and perfect our new forms of government, and to prepare the principles, morals, and manners of our citizens for these forms of government after they are established and brought to perfection.

- Benjamin Rush, Letter to Price, (25 May 1786).

- The establishment of our new government seemed to be the last great experiment for promoting human happiness by a reasonable compact in civil society. It was to be in the first instance, in a considerable degree, a government of accommodation as well as a government of laws. Much was to be done by prudence, much by conciliation, much by firmness. Few, who are not philosophical spectators, can realize the difficult and delicate part, which a man in my situation had to act. All see, and most admire, the glare which hovers round the external happiness of elevated office. To me there is nothing in it beyond the lustre, which may be reflected from its connection with a power of promoting human felicity.

- George Washington, letter to Catharine Macaulay Graham (9 January 1790), New York.

- As it was 189 years ago, so today the cause of America is a revolutionary cause. And I am proud this morning to salute you as fellow revolutionaries. Neither you nor I are willing to accept the tyranny of poverty, nor the dictatorship of ignorance, nor the despotism of ill health, nor the oppression of bias and prejudice and bigotry. We want change. We want progress. We want it both abroad and at home—and we aim to get it.

- Lyndon B. Johnson, remarks to college students employed by the government during the summer (August 4, 1965); in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1965, book 2, p. 830

- But above all, what this Congress can be remembered for is opening the way to a new American revolution—a peaceful revolution in which power was turned back to the people—in which government at all levels was refreshed and renewed and made truly responsive. This can be a revolution as profound, as far-reaching, as exciting as that first revolution almost 200 years ago—and it can mean that just 5 years from now America will enter its third century as a young nation new in spirit, with all the vigor and the freshness with which it began its first century.

- Richard Nixon, State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress (January 22, 1971); in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Richard Nixon, 1971, p. 58

- The principles of our fathers in regard to human liberty and equality still live.

- Owen Lovejoy, acceptance speech on receiving unanimous renomination at the Joliet Convention in Illinois, as quoted in His Brother's Blood: Speeches and Writings, 1838–64 (2004), edited by William Frederick Moore and Jane Ann Moore, p. 158.

- Today's soldiers, and the democratic fallen, now occupy a prominent place in a long tradition of American liberators, extending from the American Revolution.

- Joseph Morrison Skelly, "The Democratic Fallen: Let us honor those who have defended our right to self-government with their last breaths" (18 May 2007), National Review Online.

- Not only do I pray for it, on the score of human dignity, but I can clearly forsee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union, by consolidating it in a common bond of principle.

- Attributed to George Washington, John Bernard, Retrospections of America, 1797–1811, p. 91 (1887). This is from Bernard's account of a conversation he had with Washington in 1798. Reported as unverified in Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations (1989).

- Republicanism did not die away. They remain to temper the scramble for private wealth and happiness and they continue to underlie for many of our ideals and aspirations: for our belief in equality and our dislike of pretension and privilege; our deep yearning for individual autonomy and freedom from all ties of dependency; our periodic hopes, expressed, for example, in the election of military heroes and in the mugwump and progressive movements, that some political leaders might rise above parties and become truly disinterested umpires and deliberative representatives; our long-held conviction that farming is morally healthier and freer of selfish marketplace concerns than other activities; our preoccupation with the fragility of the republic and its liability to corruption; and, finally, our remarkable obsession with our own national virtue-an obsession that still bewilders the rest of the world.

- Gordon S. Wood, "Classical Republicanism and the American Revolution" (April 1990), Chicago-Kent Law Review.

- The revolution did more than legally create the United States; it transformed American society... Far from remaining monarchical, hierarchy-ridden subjects on the margin of civilization, Americans had become, almost overnight, the most liberal, the most democratic, the most commercial minded, and the most modern people in the world... The Revolution did not merely create a political and legal environment conducive to economic expansion; it also released powerful popular entrepreneurial and commercial energies that few realized existed and transformed the economic landscape of the country. In short, the Revolution was the most radical and most far-reaching event in American history.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1991), pp. 6–8.

- All the leading Founders affirmed on many occasions that blacks are created equal to whites and that slavery is wrong... The whole Revolution was an antislavery movement, for the colonists. The political logic of the Revolution pointed inexorably to the eventually abolition of slavery for the blacks as well... Americans did come to understand the meaning of their principles more fully as the Revolution proceeded. But with respect to slavery, they knew by the end of the founding era exactly what their principles meant. The more they based their arguments on the natural rights of all men, and not just the rights of Englishmen, the more the Americans noticed, by the same logic, that enslavement of blacks was also unjust... Slaves themselves appealed to the natural rights argument. In our time, the principles of the Revolution have been denounced as 'white' or 'Eurocentric'. It is true that a tiny minority of European philosophers, who opposed the convictions of most whites of their day, first published those principles to the world. But whoever may have discovered them, American whites and blacks alike came to believe that the natural rights of mankind, like the laws of gravity discovered by Newton, were not some ethnocentric ideology but God's own truth.

- Thomas West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., pp. 4–7.

- When the decision was finally made to accept blacks as full citizens, the founders' principles provided the theoretical foundation. Lincoln's revival of the declaration in the 1850s had prepared the way. In principle, people of all races can become citizens of a nation based on the idea that 'all men are created equal'.

- Thomas West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., p. 28.

- Lincoln and the Republican Party of the 1850s were able to mobilize a national majority against the expansion of slavery only because of the commitment the founders had made to the proposition that all men are created equal. The Republican opposition to slavery led to secession and civil war. After the border slave states had become committed to the war effort Lincoln took his earliest practical opportunity to announce the Emancipation Proclamation. From then on, the war for the Union became a war to abolish slavery... The founders believed that their compromises with slavery would be corrected in the course of American history after the union was formed. Their belief turned out to be true, although the new birth of freedom proved to be less inevitable and more costly than they had anticipated. The civil war fulfilled the antislavery promise of the American founding. Lincoln was right, and today's consensus is wrong. America really was 'conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal'. Under the principles of the declaration and the law of the constitution, blacks won their liberty, became equal citizens, gained the right to vote, and eventually had their life, liberty, and property equally protected by the law. But today the founding, which made all this possible is denounced as unjust and anti-black. Surely that uncharitable verdict deserves to be reversed.

- Thomas West, Vindicating the Founders (2001), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., pp. 35–36.

Quotes about American Revolution

[edit]- Traditionally, the Battle of Saratoga is credited with tipping the revolutionary scales. Yet the health of the Continental regulars involved in battle was a product of the ambitious initiative Washington began earlier that year at Morristown, close on the heels of the victorious Battle of Princeton. Among the Continental regulars in the American Revolution, 90 percent of deaths were caused by disease, and Variola the small pox virus was the most vicious of them all. (Gabriel and Metz 1992, 107)

On the 6th of January 1777, George Washington wrote to Dr. William Shippen Jr., ordering him to inoculate all of the forces that came through Philadelphia. He explained that: "Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army . . . we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy." The urgency was real. Troops were scarce and encampments had turned into nomadic hospitals of festering disease, deterring further recruitment. Both Benedict Arnold and Benjamin Franklin, after surveying the havoc wreaked by Variola in the Canadian campaign, expressed fears that the virus would be the army's ultimate downfall. (Fenn 2001, 69)

At the time, the practice of infecting the individual with a less-deadly form of the disease was widespread throughout Europe. Most British troops were immune to Variola, giving them an enormous advantage against the vulnerable colonists. (Fenn 2001, 131) Conversely, the history of inoculation in America (beginning with the efforts of the Reverend Cotton Mather in 1720) was pocked by the fear of the contamination potential of the process. Such fears led the Continental Congress to issue a proclamation in 1776 prohibiting Surgeons of the Army to inoculate.

Washington suspected the only available recourse was inoculation, yet contagion risks aside, he knew that a mass inoculation put the entire army in a precarious position should the British hear of his plans. Moreover, Historians estimate that less than a quarter of the Continental Army had ever had the virus; inoculating the remaining three quarters and every new recruit must have seemed daunting. Yet the high prevalence of disease among the army regulars was a significant deterrent to desperately needed recruits, and a dramatic reform was needed to allay their fears.

Weighing the risks, on February 5th of 1777, Washington finally committed to the unpopular policy of mass inoculation by writing to inform Congress of his plan. Throughout February, Washington, with no precedent for the operation he was about to undertake, covertly communicated to his commanding officers orders to oversee mass inoculations of their troops in the model of Morristown and Philadelphia (Dr. Shippen's Hospital). At least eleven hospitals had been constructed by the year's end.

Variola raged throughout the war, devastating the Native American population and slaves who had chosen to fight for the British in exchange for freedom. Yet the isolated infections that sprung up among Continental regulars during the southern campaign failed to incapacitate a single regiment. With few surgeons, fewer medical supplies, and no experience, Washington conducted the first mass inoculation of an army at the height of a war that immeasurably transformed the international system.- Amy Lynn Filsinger & Raymond Dwek; ”George Washington and the First Mass Military Inoculation”, Library of Congress, (February 12, 2009)

- The left charged supporters of 1776 who opposed 1789 with inconsistency. The charge was commonplace across the Atlantic world and needed answering by the right. In Europe, it was heard against Burke. In the United States, it was popular among Jeffersonian anti-Federalists. Gentz’s answer to the charge was scholastic and lawyerly. As he described them, the American Revolution was defensive; the French, offensive. The Americans were defending established rights that had been injured or abridged by the British. Their aims were fixed and limited. Revolution prompted little resistance from within the colonies; widespread support for independence created a nation. The French Revolution stood in contrast on each point. The revolutionaries usurped power and trampled on rights. They had no aim but set off “in a thousand various directions, continually crossing each other.” Far from creating a unified nation, they provoked a mass of resistance and plunged the country into civil war. The good American and the bad French Revolutions became part of conservatism’s intellectual armory.

- Edmund Fawcett, Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition (2020), p. 36

- To the extent that 1776 led to the resultant U.S., which came to captain the African Slave Trade—as London moved in an opposing direction toward a revolutionary abolition of this form of property—the much-celebrated revolt of the North American settlers can fairly be said to have eventuated as a counter-revolution of slavery.

- Gerald Horne, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (New York University Press: 2014), p. x

- Ironically, the founders of the republic have been hailed and lionized by left, right, and center for—in effect—creating the first apartheid state.

- Gerald Horne, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (New York University Press: 2014), p. 4

- The United States of America was founded by a war, and so it was needed to be a "good war." The creation of this founding myth, the rewriting of history, began immediately after the war, while everyone with short-term memory knew otherwise. Collective amnesia was a small further sacrifice for nation building. Most schoolchildren today are given the impression that the American Revolution was a relatively benign war. The worst thing that happened outside of the Continental Army being cold in the winter was the hanging of Nathan Hale, before which he got to make a speech asserting his willingness to be hanged. In truth, the American Revolution was a brutal civil conflict filled with not only combat casualties but bitter feuds and abuses between civilians and between military and civilians. A higher percentage of the American population died in the Revolution than in any other war in U.S. history except the undeniably brutal Civil War. The Revolution, like most civil wars, was a war against civilians, a war in which women and children and the homes in which they lived were often deliberately and viciously targeted. Civilians would run in terror at the approach of either army. Homes were sacked and women were raped.

- Mark Kurlansky, Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea (2006), ISBN 9780679643357