Interstellar (film)

Appearance

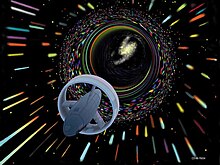

Interstellar is a 2014 science fiction film about a team of astronauts who travel through a cosmic wormhole in search of a habitable planet as the Earth is ravaged by worldwide crop blights, dust storms and the atmosphere loses oxygen.

- Directed by Christopher Nolan. Written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan.

Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here. taglines

Cooper

[edit]

- This world's a treasure, but it's been telling us to leave for a while now.

- Once you're a parent, you're the ghost of your children's future.

- We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars, now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.

- Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here.

- We've always defined ourselves by the ability to overcome the impossible. And we count these moments. These moments when we dare to aim higher, to break barriers, to reach for the stars, to make the unknown known. We count these moments as our proudest achievements. But we lost all that. Or perhaps we've just forgotten that we are still pioneers. And we've barely begun. And that our greatest accomplishments cannot be behind us, because our destiny lies above us.

- I don't care much for this -- pretending we're back where we started. I wanna know where we are. Where we're going.

Professor Brand

[edit]- Do not go gentle into that good night;

Old age should burn and rave at close of day.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.- Quoting famous lines of the poem "Do not go gentle into that good night" by Dylan Thomas

Murphy Cooper

[edit]

- Today is my birthday. And it's a special one because you once told me that when you came back, we might be the same age. Well, now I'm the same age that you were when you left... and it'd be really great if you came back soon.

- Eureka!

- Quoting Archimedes when she finishes equations related to information from the black hole about the gravity force.

Amelia Brand

[edit]

- Maybe we've spent too long trying to figure all this out with theory.

- Love is the one thing that transcends time and space.

- You might have to decide between seeing your children again and the future of the human race.

CASE

[edit]- TARS talks plenty for both of us...

- Cooper, this is no time for caution.

TARS

[edit]- Everybody good? Plenty of slaves for my robot colony?

- I have a cue light I can use to show you when I'm joking, if you like.

Dialogue

[edit]

- Young Murph: Dad, why did you and mom name me after something that's bad?

- Cooper: Well, we didn't.

- Young Murph: Murphy's law?

- Cooper: Murphy's law doesn't mean that something bad will happen. It means that whatever can happen will happen.

- Cooper: You're ruling out college for my son now? He's 15.

- Principal: Tom's score simply isn't high enough.

- Cooper: What's your waist line? What 32, 33 inseam?

- Principal: I'm not sure I see what you're getting at.

- Cooper: You're telling me it takes two numbers to measure your own ass but only one to measure my son's future?

- Cooper: You don't believe we went to the Moon?

- Ms. Hanley: I believe it was a brilliant piece of propaganda, that the Soviets bankrupted themselves pouring resources into rockets and other useless machines...

- Cooper: Useless machines?

- Ms. Hanley: ..and if we don't want to repeat of the excess and wastefulness of the 20th Century then we need to teach our kids about this planet, not tales of leaving it.

- Cooper: You know, one of those useless machines they used to make was called an MRI, and if we had one of those left the doctors would have been able to find the cyst in my wife's brain, before she died instead of afterwards, and then she would've been the one sitting here, listening to this instead of me. Which would've been a good thing because she was always the ... calmer one.

- Prof. Brand: We must confront the reality that nothing in our solar system can help us.

- Cooper: Now you need to tell me what your plan is to save the world.

- Prof. Brand: We're not meant to save the world. We're meant to leave it, and this is the mission you were trained for.

- Cooper: I've got kids, Professor.

- Prof. Brand: Then get out there and save them. We must reach far beyond our own lifespans. We must think not as individuals but as a species. We must confront the reality of interstellar travel.

- Cooper: It is hard leaving everything... my kids, your father...

- Brand: We're gonna be spending a lot of time together.

- Cooper: We should learn to talk.

- Brand: And when not to? … Just being honest.

- Cooper: I don't think you need to be that honest.

- Doyle: The lost communications came through.

- Brand: How?

- Doyle: The relay on this side cached them. Years of basic data, no real surprises. Miller's site has kept pinging thumbs up, as has Mann... but Edmunds went down three years ago.

- Brand: Transmitter failure?

- Doyle: Maybe. He was sending thumbs up right till it went dark.

- Romilly: Miller still looks good? [Doyle nods, and Romilly begins drawing on a whiteboard] She's coming up fast ... with one complication: the planet is much closer to Gargantua than we thought.

- Cooper: Gargantua?

- Doyle: A very large black hole. Miller's and Dr. Mann's planets orbit it.

- Brand: And Miller's is right on the horizon?

- Romilly: A basketball on the hoop. Landing there takes us dangerously close. A black hole that big has a huge gravitational pull.

- Cooper: Look, I can swing around that neutron star and decelerate—

- Brand: It's not that, it's time. That gravity will slow our clock compared to Earth. Drastically.

- Cooper: How bad?

- Romilly: Every hour we spend down there will be maybe... seven years back on Earth.

- Cooper: Jesus...

- Romilly: That's relativity, folks.

- Cooper: Ready?

- CASE: Yup.

- Cooper: Don't say much, do you?

- CASE: TARS talks plenty for both of us.

- Cooper: We wanna get down fast, don't we?

- Brand: Actually we want to get there in one piece.

- Cooper: Hang on.

- Brand: I told you to leave me.

- Cooper: And I told you to get your ass back here! Difference is, only one of us was thinking about the mission—

- Brand: Cooper, you were thinking about getting home — I was trying to do the right thing!

- Cooper: Tell that to Doyle. [pause] How long to drain, CASE?

- CASE: Forty-five to an hour.

- Cooper: The stuff of life, huh? What's this gonna cost us, Brand?

- Brand: A lot. Decades.

- Cooper: What happened to Miller?

- Brand: Judging by the wreckage, she was broken up by a wave shortly after impact.

- Cooper: How could the wreckage still be together after all these years?

- Brand: Because of the time slippage. On this planet's time, she landed here just hours ago. She might have died only minutes ago.

- CASE: The data Doyle collected was just the initial status, echoing endlessly.

- Cooper: We're not prepared for this, Brand. You're a bunch of eggheads without the survival skills of a boy-scout troop.

- Brand: We got this far on our brains, farther than any humans in history...

- Cooper: No, not far enough. And we're stuck here till there won't be anyone left on Earth to save—

- Brand: I'm counting every second, same as you, Cooper.

- Cooper: Don't you have some clever way we jump into a black hole and get back the years? [Brand shakes her head] Don't you shake your head at me!

- Brand: Time is relative, it can stretch and squeeze, but it can't run backwards. The only thing that can move across dimensions like time is gravity.

- Cooper: The beings that led us here ... they communicate through gravity ... Could they be talking to us from the future?

- Brand: Maybe.

- Cooper: Well, if they can—

- Brand: Look, Cooper, they're creatures of at least five dimensions, to them the past might be a canyon they can climb into and the future a mountain they can climb up... but to us it's not, okay? I'm sorry, Cooper. I screwed up. But you know about relativity.

- Cooper: My daughter was ten. I couldn't explain Einstein's theories before I left.

- Brand: Could you tell her you were going to save the world?

- Cooper: No. I wasn't much of a parent, but I understood the most important thing — let your kids feel safe. Which rules out telling ten-year-old that the world's ending.

- Cooper:[As he tries to reconfigure TARS personality settings] Humour 75%.

- TARS: Confirmed. Self destruct sequence in T minus 10… 9…

- Cooper: Let's make that 60%.

- TARS: 60%, confirmed. Knock, knock.

- Cooper: You want fifty-five?

- TARS: [As Cooper suddenly accelerates towards an out-of-control Endurance] Cooper, there's no point in using our fuel to chase-

- Cooper: Analyze the Endurance's spin.

- Brand: Cooper, what are you doing?!

- Cooper: Docking.

- CASE: This is not possible.

- Cooper: No. It's necessary.

- Cooper: What's your trust setting, TARS?

- TARS: Lower than yours, apparently.

- Murph: [as Cooper holds his now elderly daughter's hands] Nobody believed me, but I knew you'd come back.

- Cooper: How?

- Murph: ...Because my dad promised me.

Taglines

[edit]- Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here.

- Go further.

- The end of Earth will not be the end of us.

- Mankind's next step will be our greatest.

Cast

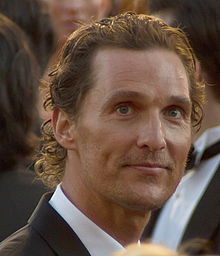

[edit]- Matthew McConaughey - Cooper, a widowed astronaut

- Anne Hathaway - Amelia Brand, the daughter of Professor Brand

- David Gyasi - Romilly

- Wes Bentley - Doyle

- Bill Irwin - the voice of TARS, a robot

- Josh Stewart - the voice of CASE, a robot

- Matt Damon - Dr. Mann

- Jessica Chastain - Murphy "Murph" Cooper, Cooper's daughter

- Mackenzie Foy - young Murphy

- Ellen Burstyn - elderly Murphy

- Michael Caine - Professor Brand

- Casey Affleck - Tom Cooper, Cooper's son

- Timothée Chalamet - Young Tom

- John Lithgow - Donald, Cooper's father-in-law

- Leah Cairns - Lois Cooper, Tom's wife

Quotes about Interstellar

[edit]

- The Times' Kenneth Turan gave a glowing review, writing that "though it's a big studio blockbuster with all the traditional plot elements the term implies, 'Interstellar' turns out to be the rarest beast in the Hollywood jungle. It's a mass audience picture that's intelligent as well as epic, with a sophisticated script that's as interested in emotional moments as immersive visuals. Which is saying a lot."

- The New York Times' A.O. Scott wrote, "It may be enough to say that 'Interstellar' is a terrifically entertaining science-fiction movie, giving fresh life to scenes and situations we've seen a hundred times before, and occasionally stumbling over pompous dialogue or overly portentous music."

- USA Today's Claudia Puig was more measured in her appraisal, writing, "While it reaches for the stars, director Christopher Nolan's 'Interstellar ' is a flawed masterpiece. The story is ever-ambitious, sometimes riveting and thought-provoking, but also plodding and hokey and not as visionary as its cutting-edge visual effects. And at nearly three hours, the film would have benefited from more judicious editing."

- The Associated Press' Jake Coyle said that at its heart, "Interstellar" is "a father-daughter tale grandly spun across a cosmic tapestry. He continued: "There is turbulence along the way. 'Interstellar' is overly explanatory about its physics, its dialogue can be clunky and you may want to send composer Hans Zimmer's relentless organ into deep space. But if you take these for blips rather than black holes, the majesty of 'Interstellar' is something to behold."

- For the Washington Post's Ann Hornaday, the film didn't quite come together. She said that "there are moments of genuine awe and majesty in 'Interstellar,' but there are just as many passages that play as if Nolan is less interested in value for the viewers than proving a point, whether about the arcana of quantum physics, his technical prowess or the enduring power of love."

McConaughey makes for "a compelling, even believable hero," she continued, but "too often, the father-daughter dynamics that propel 'Interstellar' ... feel shrewdly calculated, the emotionalism ginned up to a hysterically maudlin pitch." Ultimately, the film "tries so hard to be so many things that it winds up shrinking into itself, much like one of the collapsed stars [McConaughey's character] hurtles past on his way to new worlds." - And the Boston Globe's Ty Burr wrote, "there's only so much you can pile on the pie plate before it starts spilling rhubarb on the floor. The parts of 'Interstellar' that don't work ... struggle against the many parts that do. Nolan is one of the few working filmmakers with the skill set to take us far beyond our normal moviegoing orbit, but his vision keeps coming up against the curves of the known pop universe. He's the showman who fancies himself a philosopher."

- Oliver Gettell, "'Interstellar' is an ambitious, imperfect sci-fi epic, reviews say", Las Angeles Times, (Nov 5, 2014).

- The movies you grow up with, the culture you absorb through the decades, become part of your expectations while watching a film. So you can't make any film in a vacuum. We're making a science-fiction film... You can't pretend 2001 doesn't exist when you're making Interstellar. … I grew up in an era that was the golden age of blockbusters, with films like Close Encounters and the way that addressed the idea of this moment when humans would meet aliens from a family perspective and a very relatable human perspective. I liked the idea of trying to give today’s audiences some sense of that form of storyline.

- I think really space exploration, to me, has always represented the most hopeful and optimistic endeavor that mankind has ever really engaged with. I was certainly struck when they flew the space shuttle in, the 747 when it came to the science center here in LA, were up in Griffith Park with hundreds of people waving flags and watching this thing fly down and it was a very moving moment actually, and a little melancholy at the same time, because what we felt was that sense of that great endeavor, that great collective endeavor, the hope and optimism of that is something it feels like we’re in need of again. I feel very strongly that we’re at a point now where we need to start looking out again and exploring our place in the universe more.

- I had the advantage of coming to the project late, being able to look at what these guys had done, and a lot of my contribution was stripping things down, because they put in all these incredible mind-blowing ideas but I felt that it was more than I could absorb as an audience member. So I spent a lot of time in my work on the script kind of choosing what I thought were the most emotive, the most tactile of these ideas, things I could really grab a hold of. Then I found working with Kip to be very liberating because it wasn’t so much restraint of “well, science says you can’t do this”, it was more an exploration of ideas with him of “OK, what’s plausible? We could go here, we could go there.” I found it very exciting to work with him on that.

- I don’t like to talk about messages so much with films simply because it’s a little more didactic. The reason I’m a filmmaker is to tell stories and so you hope that they will have resonance for people and for the kind of things you’re talking about, but what I always loved about Jonah’s original draft, and we always retained this, was the idea of blight, the idea of there being an agricultural crisis, which has happened historically if you look at the potato famine and so forth. We combined this with ideas taken very much from Ken Burns documentary on the Dust Bowl and spoke to Ken at great length and availed ourselves of his resources, because what struck me about the dust bowl is it was man-made environmental crisis, but one where the imagery – the effect of it was so outlandish we actually had to tone it down for what we put in the film. But the real point is they’re non-specific, that we’re saying that in our story man-kind is being gently nudged off the planet by the earth itself and the reason is non-specific, because we don’t want to be too didactic or too political about it. That’s not really the point. For me it goes back to something Emma said earlier, which was that my excitement about the project was addressing a possibly extremely negative idea, in terms of the planet having had enough of us and suggesting that we go somewhere else, but that being an opportunity, that being a great exciting adventure to be on was something I found very winning about it.

- Christopher Nolan in Christopher Nolan, Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and More Talk INTERSTELLAR, the Evolution of the Script, and Grounding the Film with Emotion" by Steve 'Frosty' Weintraub, Collider, (November 8, 2014).

- It’s very straightforward: selfishness and cowardice. It’s very human, and I love what Matt did with that; he found the reality of it. It’s the kind of sequence where you loathe the guy because he’s doing something that you feel you might wind up doing in a similar situation. It’s very logical, but the rationalization of it is extraordinary — the way he was able to rationalize his own cowardice into a positive thing. Loneliness and desperation will make us do crazy things.

- [Mann is] not exactly crazy. It’s weirdly logical, but appallingly selfish. The only outcome to the mission for him was [a colony]. I think, and it’s something we talked a lot about — and it’s something he says in the film — that there was no doubt in his mind that his was going to be the planet, his was going to be the mission. So whatever the risks, he felt very confident. And when he’s confronted by the bleak reality of just dying out there alone, it all starts to unravel.

- The inception of the project for me began in 2006 or 2007, that was when I first started thinking about it – and I was struck in that moment by what felt, for a variety of reasons, felt like to be growing up in this age, to be growing up in this country, in this moment in time – there’s a line about this in the film – it feels like every day is Christmas. There’s some remarkable technology, there’s some remarkable thing. You get to a certain moment where you realize all those humans who landed on the moon did so in between Chris being born and me being born and no one had gone back since, all these Super-8 films we grew up watching of rocket launches, you get to a certain age and you realize all the speeches about going back, they’re speeches, there’s no money there, we’re not going back. And that moment, it felt like the melancholy or the sadness of that was to imagine as a species that we might have peaked, that if you charted our evolution as a species in terms of altitude, we peaked in 1973. That was kind of a sad realization. Growing up you’re promised jet packs and we got Instagram. Kind of a bum deal, I think. So I was rooted in the optimism of what is the next moment in which we start to journey again.

- Jonathan Nolan in Christopher Nolan, Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and More Talk INTERSTELLAR, the Evolution of the Script, and Grounding the Film with Emotion" by Steve 'Frosty' Weintraub, Collider, (November 8, 2014).

- The state-of-the-art sci-fi landscapes are deployed in service of Hallmark card homilies about how people should live, and what’s really important. ("We love people who have died—what's the social utility in that?" "Accident is the first step in evolution.") After a certain point it sinks in, or should sink in, that Nolan and his co-screenwriter, brother Jonathan Nolan, aren’t trying to one-up the spectacular rationalism of “2001." The movie's science fiction trappings are just a wrapping for a spiritual/emotional dream about basic human desires (for home, for family, for continuity of bloodline and culture), as well as for a horror film of sorts—one that treats the star voyagers’ and their earthbound loved ones’ separation as spectacular metaphors for what happens when the people we value are taken from us by death, illness, or unbridgeable distance. (“Pray you never learn just how good it can be to see another face,” another astronaut says, after years alone in an interstellar wilderness.)

While "Interstellar" never entirely commits to the idea of a non-rational, uncanny world, it nevertheless has a mystical strain, one that's unusually pronounced for a director whose storytelling has the right-brained sensibility of an engineer, logician, or accountant. There's a ghost in this film, writing out messages to the living in dust. Characters strain to interpret distant radio messages as if they were ancient texts written in a dead language, and stare through red-rimmed eyes at video messages sent years ago, by people on the other side of the cosmos. "Interstellar" features a family haunted by the memory of a dead mother and then an absent father; a woman haunted by the memory of a missing father, and another woman who's separated from her own dad (and mentor), and driven to reunite with a lover separated from her by so many millions of miles that he might as well be dead. - The film's widescreen panoramas feature harsh interplanetary landscapes, shot in cruel Earth locales; some of the largest and most detailed starship miniatures ever built, and space sequences presented in scientifically accurate silence, a la "2001." But for all its high-tech glitz, "Interstellar" has a defiantly old-movie feeling. It's not afraid to switch, even lurch, between modes. At times, the movie's one-stop-shopping storytelling evokes the tough-tender spirit of a John Ford picture, or a Steven Spielberg film made in the spirit of a Ford picture: a movie that would rather try to be eight or nine things than just one. Bruising outer-space action sequences, with astronauts tumbling in zero gravity and striding across forbidding landscapes, give way to snappy comic patter (mostly between Cooper and the ship's robot, TARS, designed in Minecraft-style, pixel-ish boxes, and voiced by Bill Irwin). There are long explanatory sequences, done with and without dry-erase boards, dazzling vistas that are less spaces than mind-spaces, and tearful separations and reconciliations that might as well be played silent, in tinted black-and-white, and scored with a saloon piano. (Spielberg originated "Interstellar" in 2006, but dropped out to direct other projects.)

McConaughey, a super-intense actor who wholeheartedly commits to every line and moment he's given, is the right leading man for this kind of film. Cooper proudly identifies himself as an engineer as well as an astronaut and farmer, but he has the soul of a goofball poet; when he stares at intergalactic vistas, he grins like a kid at an amusement park waiting to ride a new roller coaster. Cooper's farewell to his daughter Murph—who's played by McKenzie Foy as a young girl—is shot very close-in, and lit in warm, cradling tones; it has some of the tenderness of the porch swing scene in "To Kill a Mockingbird." When Murph grows up into Jessica Chastain—a key member of Caine's NASA crew, and a surrogate for the daughter that the elder Brand "lost' to the Endurance's mission—we keep thinking about that goodbye scene, and how its anguish drives everything that Murph and Cooper are trying to do, while also realizing that similar feelings drive the other characters—indeed, the rest of the species. (One suspects this is a deeply personal film for Nolan: it's about a man who feels he has been "called" to a particular job, and whose work requires him to spend long periods away from his family.)- Matt Zoller Seitz, "Interstellar", RogerEbert.com, (November 3, 2014).

External links

[edit]Categories:

- 2014 films

- Space adventure films

- 2010s American films

- Science fiction films

- Time travel films

- Robot films

- Films about astronauts

- Screenplays by Christopher Nolan

- Films about time

- Films about widowhood

- Films directed by Christopher Nolan

- Films set on fictional planets

- Fiction about intergalactic travel

- Films about father–daughter relationships