Populism

Appearance

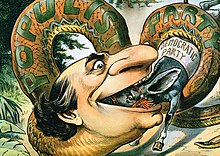

Populism is a political doctrine that proposes that the common people are exploited by a privileged elite, and which seeks to resolve this.

Quotes

[edit]- Catering to populist anger with extremist proposals that are certain to fail is not a viable strategy for political success.

- Max Boot, How the ‘Stupid Party’ Created Trump. The New York Times (August 2, 2016).

- No chord in populism reverberates more strongly than the notion that the robust common sense of an unstained outsider is the best medicine for an ailing polity. Caligula doubtless got big cheers from the plebs when he installed his horse as proconsul.

- Alexander Cockburn. "Obama's Speech; McCain's Palinomy," CounterPunch (August 30 -31, 2008).

- When Donald Trump accepts the Republican nomination on Thursday in Cleveland, it will represent a stunning moment in American politics - The triumph of a raw populism, embodied by a shameless demagogue, over both the official establishment and the official ideology of a major political party.

- Ross Douthat, A Cure for Trumpism The New York Times (July 17, 2016)

- Ur-Fascism is based upon a selective populism, a qualitative populism, one might say. In a democracy, the citizens have individual rights, but the citizens in their entirety have a political impact only from a quantitative point of view—one follows the decisions of the majority. For Ur-Fascism, however, individuals as individuals have no rights, and the People is conceived as a quality, a monolithic entity expressing the Common Will. Since no large quantity of human beings can have a common will, the Leader pretends to be their interpreter. Having lost their power of delegation, citizens do not act; they are only called on to play the role of the People. Thus the People is only a theatrical fiction.

- Umberto Eco, "Ur-Fascism", New York Review of Books (June 22, 1995).

- There is a historic battle going on across the west, in Europe, America, and elsewhere. It is globalism against populism. And you may loathe populism, but I’ll tell you a funny thing. It is becoming very popular! And it has great benefits. No more financial contributions, no more European Courts of Justice. No more European Common Fisheries Policy, no more being talked down to. No more being bullied, no more Guy Verhofstadt! What’s not to like. I know you’re going to miss us, I know you want to ban our national flags, but we’re going to wave you goodbye, and we’ll look forward in the future to working with you as a sovereign nation… [Farage is cut off by the chair]

- Nigel Farage, EU Farewell Speech, as quoted in Nigel Farage’s Final EU Speech: Mic Gets Cut as He Waves UK Flag in Victory, Breitbart news

- Populism is a path that, at its outset, can look and feel democratic. But, followed to its logical conclusion, it can lead to democratic backsliding or even outright authoritarianism.

- Max Fisher and Amanda Taub, “How can Populism Erode Democracy? Ask Venezuela,” The New York Times, (April 2, 2017)

- Modern life requires many people of talent and intelligence to run big institutions, including governments. Others resent their quality wherever they find it. They see it as oppressive. Then Donald Trump came before them and sneered at government leadership, in a style that had nothing to do with talent or intelligence.... To accomplish this, his followers needed only to mark a ballot. Soon he looked like the man they always needed. In the future, this strategy may well be called Trumpism. For now, American journalists call it populism.

- We have been given an assignment as a monarchy, and we do as well as we can … We try to be as little populistic as possible. We don't do anything on the spur of the moment to win an opinion poll, or short-term popularity.

- Harald V of Norway, Interview in Wenche Fuglehaug (November 21, 2005). "Norway's monarchy turns 100", Aftenposten, Aftenposten Multimedia A/S, Oslo, Norway.

- With a woman's selflessness and kindness, I look to end populism and political wrangling between the blue and green camps in the coming (2016 ROC) presidential election against Tsai (Ing-wen).

- Hung Hsiu-chu (2015) cited in "Refreshed Hung Hsiu-chu returns to the fray after time-out" on Want ChinaTimes, 7 September 2015

- Populism is the simple premise that markets need to be restrained by society and by a democratic political system. We are not socialists or communists, we are proponents of regulated capitalism and, I might add, people who have read American history.

- Molly Ivins, I Told You So, May 30, 2002.

- The time has come to move beyond eco-elitism to eco-populism.

- Van Jones The Green Collar Economy (2008)

- Populism is at its essence [...] just determined focus on helping people be able to get out of the iron grip of the corporate power that is overwhelming our economy, our environment, energy, the media, government. [...] One big difference between real populism and what the Tea Party thing is, is that real populists understand that government has become a subsidiary of corporations. So you can't say, let's get rid of government. You need to be saying let's take over government.

- Jim Hightower, Interview by Bill Moyers, Bill Moyers Journal, 30 April 2010 (transcript, video)

- The federalist adventure, so assured in its idealism, had always required the honouring of Rousseau’s social contract, a consensual relationship between the state and the citizen. Europe’s diverse peoples would support union, but only insofar as it did not infringe their perceived character and way of life. Europe’s booming cities might be able to absorb change, but this was not true of formerly industrial provinces, rural areas and ageing populations. Britain’s pro-Brexit voters–heavily provincial, rural and older–reflected this divide. Parties variously labelled right-wing, nationalist or populist gained strength in most if not all European states, responding to a call for voters to ‘take back control’ of their political and social environment. Most alarmingly, the 2016 World Values Survey reported that ‘fewer than half’ of respondents born in the seventies and eighties believed it was ‘essential to live in a country that is governed democratically’. In Germany, Spain, Japan and America, between twenty and forty per cent would prefer ‘a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliaments or elections’.

- Simon Jenkins, A Short History of Europe: From Pericles to Putin (2018)

- Democrats have to figure out why the white working class just voted overwhelmingly against its own economic interests, not pretend that a bit more populism would solve the problem.

- Paul Krugman, The Populism Perplex, The New York Times (November 25, 2016)

- Building on Linz’s work, we have developed a set of four behavioral warning signs that can help us know an authoritarian when we see one. We should worry when a politician 1) rejects, in words or action, the democratic rules of the game, 2) denies the legitimacy of opponents, 3) tolerates or encourages violence, or 4) indicates a willingness to curtail the civil liberties of opponents, including the media. Table 1 shows how to assess politicians in terms of these four factors. A politician who meets even one of these criteria is cause for concern. What kinds of candidates tend to test positive on a litmus test for authoritarianism? Very often, populist outsiders do. Populists are antiestablishment politicians—figures who, claiming to represent the voice of “the people,” wage war on what they depict as a corrupt and conspiratorial elite. Populists tend to deny the legitimacy of established parties, attacking them as undemocratic and even unpatriotic. They tell voters that the existing system is not really a democracy but instead has been hijacked, corrupted, or rigged by the elite. And they promise to bury that elite and return power to “the people.” This discourse should be taken seriously. When populists win elections, they often assault democratic institutions. In Latin America, for example, of all fifteen presidents elected in Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela between 1990 and 2012, five were populist outsiders: Alberto Fujimori, Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, Lucio Gutiérrez, and Rafael Correa. All five ended up weakening democratic institutions.

- Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt (2018) How Democracies Die. New York: Crown.

- When Reagan and Thatcher came to power, “authoritarian populism” was a term academics used to describe their politics. Now it’s a phenomenon, growing rapidly, cutting across old definitions of left and right, goes the argument. But it’s not so simple and the phenomenon is not new. The term “authoritarian populist” is a construct that, if we are not careful, could blind us to the real roots of centrism’s sudden crisis – and to the answers.

- Paul Mason How do we fight the loudmouth politics of authoritarian populism?, The Guardian (21 November 2016)

- Popularity is what you get when lots of people like a thing. Populism is what you get when a small group of people tell you that everyone likes a thing and if you don’t like it, you’re a traitor.

- Phil McDuff, "Got some bad opinions? Here's how to sound like the authentic voice of the working class," The Overtake, July 30, 2018.

- The growing power of political lobbies has given moneyed interests undue influence over policymaking, and has endowed a new class of politician with the ability not only to fundamentally misunderstand their constituents but to be rewarded for this. Socioeconomic inequality, which for much of the postwar era had been warded off by the welfare state, has returned. In response to such developments, the streets of Western capitals have been marched upon by people in larger numbers than at any time since the high point of the civil rights movement half a century ago. Whether it is Occupy protesters or the gilets jaunes, white supremacists or national populists, a more assertive voice is emerging beneath the battered wing of liberal democracy and its representative institutions. Some of these movements are utopian, others demand greater rights, if only for themselves. But everywhere the clamor of popular disapproval is growing and is making its presence felt in the cordoned halls of liberal democratic debate. Democracy itself is changing before our eyes.

- Simon Reid-Henry, Empire of Democracy: The Remaking of the West Since the Cold War, 1971-2017 (2019), pp. 1-2

- The West has unfortunately already started to go along this path. I know, to many it may sound ridiculous to suggest that the West has turned to socialism, but it's only ridiculous if you only limit yourself to the traditional economic definition of socialism, which says that it's an economic system where the state owns the means of production. This definition in my view, should be updated in the light of current circumstances. Today, states don't need to directly control the means of production to control every aspect of the lives of individuals. With tools such as printing money, debt, subsidies, controlling the interest rate, price controls, and regulations to correct so-called market failures, they can control the lives and fates of millions of individuals. This is how we come to the point where, by using different names or guises, a good deal of the generally accepted ideologies in most Western countries are collectivist variants, whether they proclaim to be openly communist, fascist, socialist, social democrats, national socialists, Christian democrats, neo-Keynesians, progressives, populists, nationalists or globalists. Ultimately, there are no major differences. They all say that the state should steer all aspects of the lives of individuals. They all defend a model contrary to the one that led humanity to the most spectacular progress in its history.

- Javier Milei, Special Address to the World Economic Forum, 18 January 2024

- "Populists" believe in conspiracies and one of the most enduring is that a secret group of international bankers and capitalists, and their minions, control the world's economy.

- David Rockefeller, Memoirs (2003), Ch. 27 : Proud Internationalist, p. 406

- As Part IV of this book will chart, the financial and economic crisis of 2007–2012 morphed between 2013 and 2017 into a comprehensive political and geopolitical crisis of the post–cold war order. And the obvious political implication should not be dodged. Conservatism might have been disastrous as a crisis-fighting doctrine, but events since 2012 suggest that the triumph of centrist liberalism was false too. As the remarkable escalation of the debate about inequality in the United States has starkly exposed, centrist liberals struggle to give convincing answers for the long-term problems of modern capitalist democracy. The crisis added to those preexisting tensions of increasing inequality and disenfranchisement, and the dramatic crisis-fighting measures adopted since 2008, for all their short-term effectiveness, have their own, negative side effects. On that score the conservatives were right. Meanwhile, the geopolitical challenges thrown up, not by the violent turmoil of the Middle East or “Slavic” backwardness but by the successful advance of globalization, have not gone away. They have intensified. And though the “Western alliance” is still in being, it is increasingly uncoordinated. In 2014 Japan lurched toward confrontation with China. And the EU—the colossus that “does not do geopolitics”—“sleepwalked” into conflict with Russia over Ukraine. Meanwhile, in the wake of the botched handling of the eurozone crisis, Europe witnessed a dramatic mobilization on both Left and Right. But rather than being taken as an expression of the vitality of European democracy in the face of deplorable governmental failure, however disagreeable that expression may in some cases be, the new politics of the postcrisis period were demonized as “populism,” tarred with the brush of the 1930s or attributed to the malign influence of Russia. The forces of the status quo gathered in the Eurogroup set out to contain and then to neutralize the left-wing governments elected in Greece and Portugal in 2015. Backed up by the newly enhanced powers of the fully activated ECB, this left no doubt about the robustness of the eurozone. All the more pressing were the questions about the limits of democracy in the EU and its lopsidedness. Against the Left, preying on its reasonableness, the brutal tactics of containment did their job. Against the Right they did not, as Brexit, Poland and Hungary were to prove.

- Adam Tooze Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World (2018)

- populism, which is regularly invoked as a model by the majoritarians, is at bottom a form of identity politics or cultural nationalism for so-called ordinary people. Populism and "workerism," like other variants of nationalism, define membership in a political community through the exclusion of others and defend the received values of that community against outsiders. Such movements equate collective values with dominant values, denying conflict and punishing dissidence within their own ranks.

- Ellen Willis "The Majoritarian Fallacy" in Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

- No mass left-wing movement has ever been built on a majoritarian strategy. On the contrary, every such movement-socialism, populism, labor, civil rights, feminism, gay rights, ecology-has begun with a visionary minority whose ideas were at first decried as impractical, ridiculous, crazy, dangerous, and/or immoral.

- Ellen Willis "The Majoritarian Fallacy" in Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)