Oliver Cromwell

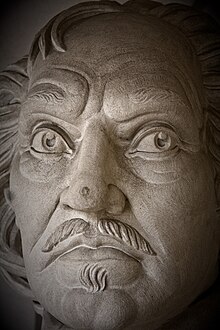

Appearance

(Redirected from Cromwell)

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English statesman, soldier, and revolutionary responsible for the overthrow of the monarchy, temporarily turning England into a republican Commonwealth, and assuming rule as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. After he died his son Richard Cromwell took this position, until King Charles II was crowned king.

Quotes

[edit]

1643

[edit]- If the remonstrance had been rejected I would have sold all I had the next morning and never have seen England more, and I know there are many other modest men of the same resolution.

- On the passing of the revolutionary Grand Remonstrance of November 1641 listing Parliament's grievances against King Charles I, as quoted in A History of the Rebellion (first published 1702 – 1704) by Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon (1609 - 1674)

- I had rather have a plain, russet-coated Captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that you call a Gentleman and is nothing else.

- Letter to Sir William Spring (September 1643)

- A few honest men are better than numbers.

- Letter to Sir William Spring (September 1643)

- The State, in choosing men to serve it, takes no notice of their opinions; if they be willing faithfully to serve it – that satisfies. I advised you formerly to bear with men of different minds from yourself:

- Letter to Lawrence Crawford (10 March 1643)

1644

[edit]- God made them as stubble to our swords.

- Letter to Colonel Valentine Walton (5 July 1644), following the Battle of Marston Moor.

- Truly England and the church of God hath had a great favour from the Lord, in this great victory given us.

- Letter to Colonel Valentine Walton (5 July 1644)

- We study the glory of God, and the honour and liberty of parliament, for which we unanimously fight, without seeking our own interests... I profess I could never satisfy myself on the justness of this war, but from the authority of the parliament to maintain itself in its rights; and in this cause I hope to prove myself an honest man and single-hearted.

- Statement to Colonel Valentine Walton (5 or 6 September 1644)

1645

[edit]- I could not riding out alone about my business, but smile out to God in praises, in assurance of victory because God would, by things that are not, bring to naught things that are.

- Before the Battle of Naseby (14 June 1645)

1646

[edit]- It's a blessed thing to die daily. For what is there in this world to be accounted of! The best men according to the flesh, and things, are lighter than vanity. I find this only good, to love the Lord and his poor despised people, to do for them and to be ready to suffer with them....and he that is found worthy of this hath obtained great favour from the Lord; and he that is established in this shall ( being conformed to Christ and the rest of the Body) participate in the glory of a resurrection which will answer all.

- Letter to Sir Thomas Fairfax (7 March 1646)

- This is our comfort, God is in heaven, and He doth what pleaseth Him; His, and only His counsel shall stand, whatsoever the designs of men, and the fury of the people be.

- Letter to Sir Thomas Fairfax (21 December 1646)

- We declared our intentions to preserve monarchy, and they still are so, unless necessity enforce an alteration. It’s granted the king has broken his trust, yet you are fearful to declare you will make no further addresses... look on the people you represent, and break not your trust, and expose not the honest party of your kingdom, who have bled for you, and suffer not misery to fall upon them for want of courage and resolution in you, else the honest people may take such courses as nature dictates to them.

- Speech in the Commons during the debate which preceded the "Vote of No Addresses" (January 1648) as recorded in the diary of John Boys of Kent

1648

[edit]- Since providence and necessity has cast them upon it, he should pray God to bless their counsels.

- On the trial of Charles I (December 1648)

- I tell you we will cut off his head with the crown upon it.

- To Algernon Sidney, one of the judges at the trial of Charles I (December 1648)

- Cruel necessity.

- Reported remarks over the body of Charles I after his execution (January 1649), as quoted in Oliver Cromwell : A History (1895) by Samuel Harden Church, p. 321

1649

[edit]- If we do not depart from God, and disunite by that departure, and fall into disunion among ourselves, I am confident, we doing our duty and waiting upon the Lord, we shall find He will be as a wall of brass round about us till we have finished that work which he has for us to do.

- Speech to his army officers (23 March 1649)

- This is a righteous judgement of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood.

- After the Siege of Drogheda, where Cromwell had forbid his soldiers "to spare any that were in arms in the town" (1649)

- Do not trust to that; for these very persons would shout as much if you and I were going to be hanged.

- Response to John Lambert's remarks that he "was glad to see we had the nation on our side" as they were cheered by a crowd in June 1650; as quoted by Gilbert Burnet in History of My Own Time (1683); also in in God's Englishman by Christopher Hill (1970), Ch. VII, p. 188

1650

[edit]- I need pity. I know what I feel. Great place and business in the world is not worth looking after.

- Letter to Richard Mayor (July 1650)

- I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.

- Letter to the general assembly of the Church of Scotland (3 August 1650)

- Your pretended fear lest error should step in, is like the man that would keep all the wine out of the country lest men should be drunk. It will be found an unjust and unwise jealousy, to deny a man the liberty he hath by nature upon a supposition that he may abuse it.

- Letter to Walter Dundas (12 September 1650)

- No one rises so high as he who knows not whither he is going.

- Statement to Pomponne de Bellievre, as told to Cardinal de Retz in 1651; Memoirs of Cardinal de Retz (1717)

- Variant: One never rises so high as when one does not know where one is going.

1651

[edit]- I am neither heir nor executor to Charles Stuart.

- Repudiating a royal debt (August 1651)

- The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is for aught I know, a crowning mercy.

- Letter to William Lenthall, Speaker of the House of Commons (4 September 1651)

1652

[edit]- Shall we seek for the root of our comforts within us; what God hath done, what he is to us in Christ, is the root of our comfort. In this is stability; in us is weakness. Acts of obedience are not perfect, and therefore yield not perfect peace. Faith, as an act, yields it not, but as it carries us into him, who is our perfect rest and peace; in whom we are accounted of, and received by, the Father, even as Christ himself. This is our high calling. Rest we here, and here only.

- Letter to Charles Fleetwood (1652)

1653

[edit]- It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonoured by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice; ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government; ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of pottage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money. Is there a single virtue now remaining amongst you? Is there one vice you do not possess? Ye have no more religion than my horse; gold is your God; which of you have not barter'd your conscience for bribes? Is there a man amongst you that has the least care for the good of the Commonwealth? Ye sordid prostitutes have you not defil'd this sacred place, and turn'd the Lord's temple into a den of thieves, by your immoral principles and wicked practices? Ye are grown intolerably odious to the whole nation; you were deputed here by the people to get grievances redress'd, are yourselves gone! So! Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors. In the name of God, go!

- Speech on the dissolution of the Rump of the Long Parliament (20 April 1653)

- When I went there, I did not think to have done this. But perceiving the spirit of God so strong upon me, I would not consult flesh and blood.

- On his forcible dissolution of parliament (April 1653) quoted in Flagellum: or the Life and Death Birth and Burial of Oliver Cromwell the Late Usurper (1663) by James Heath

- You are as like the forming of God as ever people were... you are at the edge of promises and prophecies.

- Speech to the "Barebones Parliament" (July 1653)

1654

[edit]- God has brought us where we are, to consider the work we may do in the world, as well as at home.

- Speech to the Army Council (1654)

- Though peace be made, yet it's interest that keep peace.

- Quoted in a statement to Parliament as as "a maxim not to be despised" (4 September 1654)

- There are some things in this establishment that are fundamental... about which I shall deal plainly with you... the government by a single person and a parliament is a fundamental... and... though I may seem to plead for myself, yet I do not: no, nor can any reasonable man say it... I plead for this nation, and all the honest men therein.

- To the First Protectorate Parliament (12 September 1654)

- In every government there must be somewhat fundamental, somewhat like a Magna Charta, that should be standing and unalterable... that parliaments should not make themselves perpetual is a fundamental.

- Speech to the First Protectorate Parliament (12 September 1654)

- Necessity hath no law. Feigned necessities, imagined necessities... are the greatest cozenage that men can put upon the Providence of God, and make pretenses to break known rules by.

- Speech to the First Protectorate Parliament (12 September 1654)

- I was by birth a gentleman, living neither in any considerable height, nor yet in obscurity. I have been called to several employments in the nation — to serve in parliaments, — and ( because I would not be over tedious ) I did endeavour to discharge the duty of an honest man in those services, to God, and his people’s interest, and of the commonwealth; having, when time was, a competent acceptation in the hearts of men, and some evidence thereof.

- Speech to the First Protectorate Parliament (12 September 1654)

1655

[edit]- I desire not to keep my place in this government an hour longer than I may preserve England in its just rights, and may protect the people of God in such a just liberty of their consciences...

- Speech dissolving the First Protectorate Parliament (22 January 1655)

- Weeds and nettles, briars and thorns, have thriven under your shadow, dissettlement and division, discontentment and dissatisfaction, together with real dangers to the whole.

- Speech dissolving the First Protectorate Parliament (22 January 1655)

- We are Englishmen; that is one good fact.

- Speech to Parliament (1655)

1657

[edit]- Truly, though kingship be not a title but a name of office that runs through the law, yet it is not so ratione nominis, but from what is signified. It is a name of office, plainly implying a Supreme Authority. Is it more, or can it be stretched to more? I say, it is a name of office, plainly implying the Supreme Authority, and if it be so, why then I would suppose, (I am not peremptory in any thing that is matter of deduction or inference of my own,) why then I should suppose that whatsoever name hath been or shall be the name, in which the Supreme Authority shall act; why, (I say) if it had been those four or five letters, or whatsoever else it had been, that signification goes to the thing. Certainly it does, and not to the name. Why then, there can be no more said, but this, why this hath been fixt, so it may have been unfixt.

- Answer to the Conference at the Committee at Whitehall, Second Protectorate Parliament (13 April 1657), quoted in The Diary of Thomas Burton, esq., volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658 (1828), pp. 496-497

1658

[edit]- And let God be judge between you and me.

- When dissolving the second Parliament of the Protectorate, 4 February 1658, also quote in Famous Sayings and their Authors, p. 6

- Men have been led in dark paths, through the providence and dispensation of God. Why, surely it is not to be objected to a man, for who can love to walk in the dark? But providence doth often so dispose.

- Answer to the Conference at the Committee at Whitehall, Second Protectorate Parliament (13 April 1657), quoted in The Diary of Thomas Burton, esq., volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658 (1828), p. 504

- You have accounted yourselves happy on being environed with a great ditch from all the world beside.

- Speech to Parliament (25 January 1658), quoted in The Diary of Thomas Burton, esq., volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658 (1828), p. 361

- That which brought me into the capacity I now stand in, was the Petition and Advice given me by you, who, in reference to the ancient Constitution, did draw me here to accept the place of Protector. There is not a man living can say I sought it, no not a man, nor woman, treading upon English ground.

- Speech to Parliament (4 February 1658), quoted in The Diary of Thomas Burton, esq., volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658 (1828), p. 465-466

- I would have been glad to have lived under my wood side, to have kept a flock of sheep, rather than undertook such a Government as this is.

- Statement to Parliament (4 February 1658) quoted in The Diary of Thomas Burton, esq., volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658 (1828), p. 466

- I would be willing to live and be farther serviceable to God and his people; but my work is done. Yet God will be with his people.

- As quoted from "Dying Sayings" of Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches by Thomas Carlyle

- It is not my design to drink or to sleep, but my design is to make what haste I can to be gone.

- Words that Cromwell spoke as he was dying and was offered a drink (3 September 1658)

- Now I see there is a people risen that I cannot win with gifts or honours, offices or places; but all other sects and people I can.

- On the Quakers, after meeting with George Fox, as quoted in Autobiography of George Fox (1694)

- Mr. Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.

- As quoted in Anecdotes of Painting in England (1762-1771) by Horace Walpole often credited as being the origin of the phrase "warts and all".

Variant: Paint me as I am. If you leave out the scars and wrinkles, I will not pay you a shilling.

- As quoted in Anecdotes of Painting in England (1762-1771) by Horace Walpole often credited as being the origin of the phrase "warts and all".

Attributed

[edit]- Put your trust in God, but keep your powder dry.

- Attributed by William Blacker (not to be confused with Valentine Blacker), who popularized the quote with his poem "Oliver's Advice", published under the pseudonym Fitz Stewart in The Dublin University Magazine, December 1834, p. 700; where the attribution to Cromwell appears in a footnote describing a "well-authenticated anecdote" that explains the poem's title. The repeated line in Blacker's poem is "Put your trust in God, my boys, but keep your powder dry".

- Variant: Trust in God and keep your powder dry.

- A man never rises so high as when he knows not whither he is going.

- As quoted by Ralph Waldo Emerson in Essays (1841), Essay X: 'Circles', p. 265

- Being comes before well-being.

- As quoted by Chief Justice John Greig Latham in his sole dissent in Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth (1951), for his argument that defence is the pre-eminent responsibility of the state

Quotes about Cromwell

[edit]- Alphabetised by author

No less renowned than war: new foes arise,

Threatening to bind our souls with secular chains:

Help us to save free conscience from the paw

Of hireling wolves whose gospel is their maw. ~ John Milton

- During a great part of the eighteenth century most Tories hated him because he overthrew the monarchy, most Whigs because he overthrew Parliament. Since Carlyle wrote, all liberals have seen in him their champion, and all revolutionists have apotheosized the first great representatives of their school; while, on the other side, their opponents have hailed the dictator who put down anarchy. Unless the socialists or the anarchists finally prevail — and perhaps even then — his fame seems as secure as human reputation is likely to be in a changing world.

- W.C. Abbott in Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell

- The commonest charge against Cromwell is hypocrisy — and the commonest basis for that is defective chronology.

- W.C Abbott in Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell

- A born soldier of humble origins, Cromwell's military record in the Civil Wars was second to none. His 'reign' as Lord Protector from 1653 to 1658 has marked him for later generations as either a visionary political figure or a loathsome tyrant, and both cases are equally arguable; his religious bigotry, and the bitter fruit it bore in Ireland, are sadly beyond dispute. He remains secure in his reputation as one of the most extraordnary Englishmen who ever lived.

- Stuart Asquith, New Model Army, 1645-1660 (1981), p. 6

- Oliver Cromwell had certainly this afflatus. One that I knew was at the battle of Dunbar, told me that Oliver was carried on with a Divine impulse; he did laugh so excessively as if he had been drunk; his eyes sparkled with spirits. He obtain’d a great victory; but the action was said to be contrary to human prudence. The same fit of laughter seized Oliver Cromwell just before the battle of Naseby; as a kinsman of mine, and a great favourite of his, Colonel J. P. then present, testified. Cardinal Mazerine said, that he was a lucky fool.

- John Aubrey in Miscellanies

- A perfect master of all the arts of dissimulation: who, turning up the whites of his eyes, and seeking the Lord with pious gestures, will weep and pray, and cant most devoutly, till an opportunity offers of dealing his dupe a knock-down blow under the short ribs.

- George Bate (1608-1669), Cromwell's physician

- To give the devil his due, he restored justice, as well distributive as commutative, almost to it’s ancient dignity and splendour; the judges without covetousness discharging their duties according to law and equity... His own court also was regulated according to a severe discipline; here no drunkard, nor whoremonger, nor any guilty of bribery, was to be found, without severe punishment. Trade began again to prosper; and in a word, gentle peace to flourish all over England.

- George Bate

- He thought secrecy a virtue, and dissimulation no vice, and simulation, that is in plain English, a lie, or perfideousness to be a tolerable fault in case of necessity.

- Richard Baxter in Reliquiae Baxterianae

- He was of a sanguine complexion, naturally of such a vivacity, hilarity and alacrity as another man is when he hath drunken a cup too much.

- Richard Baxter in Reliquiae Baxterianae

- The next morning I sent Colonel Cook to Cromwell, to let him know that I had letters and instructions to him from the King. He sent me word by the same messenger, that he dared not see me, it being very dangerous to us both, and bid me be assured that he would serve his Majesty as long as he could do it without his own ruin; but desired that I should not expect that he should perish for his sake.

- Sir John Berkeley in Memoirs of Sir John Berkeley (29 November 1647)

- When he quitted the Parliament, his chief dependence was on the Army, which he endeavoured by all means to keep in unity, and if he could not bring it to his sense, he, rather than suffer any division in it, went over himself and carried his friends with him into that way which the army did choose, and that faster than any other person in it.

- Sir John Berkeley in Memoirs of Sir John Berkeley

- A devotee of law, he was forced to be often lawless; a civilian to the core, he had to maintain himself by the sword; with a passion to construct, his task was chiefly to destroy; the most scrupulous of men, he had to ride roughshod over his own scruples and those of others; the tenderest, he had continually to harden his heart; the most English of our greater figures, he spent his life in opposition to the majority of Englishmen; a realist, he was condemned to build that which could not last.

- John Buchan in Oliver Cromwell

- Cromwell was a man in whom ambition had not wholly suppressed, but only suspended, the sentiments of religion.

- Cromwell had delivered England from anarchy. His government, though military and despotic, had been regular and orderly. Under the iron, and under the yoke, the soil yielded its produce.

- His ambassador in France at this time was Lockhart... [who] told me, that when he was sent afterwards ambassador by king Charles, he found he had nothing of that regard that was paid him in Cromwell's time.

- Gilbert Burnet, History of His Own Time, Vol. I (1833), p. 141

- [H]is maintaining the honour of the nation in all foreign countries gratified the vanity which is very natural to Englishmen; of which he was so careful, that though he was not a crowned head, yet his ambassadors had all the respects paid them which our king's ambassadors ever had: he said, the dignity of the crown was upon the account of the nation, of which the king was only the representative head; so the nation being still the same, he would have the same regards paid to his ministers.

- Gilbert Burnet, History of His Own Time, Vol. I (1833), p. 147

- Cromwell...said, he hoped he should make the name of Englishman, as great as ever that of a Roman had been.

- Gilbert Burnet, History of His Own Time, Vol. I (1833), p. 148

- The king [Charles II] told him...how they had used both himself and his brother. Borel, in great simplicity, answered: Ha! sire, c'estoit une autre chose: Cromwell estoit un grand homme, et il se faisoit craindre et par terre et par mer ['Ha! sire, it was another thing: Cromwell was a great man, and he made himself feared both by land and by sea.']. This was very rough.

- Gilbert Burnet, History of His Own Time, Vol. I (1833), p. 149

- Sylla was the first of victors; but our own

The sagest of usurpers, Cromwell; he

Too swept off the senates while he hewed the throne

Down to a block — immortal rebel! See

What crimes it costs to be a moment free

And famous through all ages.- Lord Byron in Child Harold's Pilgrimage Canto IV

- I confess I have an interest in this Mr. Cromwell; and indeed, if truth must be said, in him alone. The rest are historical, dead to me; but he is epic, still living. Hail to thee, thou strong one; hail across the longdrawn funeral-aisle and night of time!...

- Thomas Carlyle in Historical Sketches

- Oliver Cromwell, who astonished mankind by his intelligence, did not derive it from spies in the cabinet of every prince in Europe; he drew it from the cabinet of his own sagacious mind. He observed facts, and traced them forward to their consequences. From what was, he concluded what must be, and he never was deceived.

- Earl of Chatham, speech in the House of Lords (22 November 1770), quoted in W. S. Taylor and J. H. Pringle (eds.), Correspondence of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham: Vol. IV (1840), p. 9

- Cromwell rode in from the Army to his duties as a Member of Parliament. His differences with the Scots and his opposition to Presbyterian uniformity were already swaying Roundhead politics. He now made a vehement and organised attack on the conduct of the war, and its mismanagement by lukewarm generals of noble rank, namely Essex and Manchester. Essex was discredited enough after Lostwithiel, but Cromwell also charged Manchester with losing the second Battle of Newbury by sloth and want of zeal. He himself was avid for the power and command which he was sure he could wield; but he proceeded astutely. While he urged the complete reconstitution of the Parliamentarian Army upon a New Model similar to his own in the Eastern Counties, his friends in the House of Commons proposed a so-called "Self-Denying Ordinance," which would exclude members of either House from military employment. The handful of lords who still remained at Westminster realised well enough that this was an attack on their prominence in the conduct of the war, if not on their social order. But there were such compelling military reasons in favour of the measure that neither they nor the Scots, who already dreaded Cromwell, could prevent its being carried. Essex and Manchester, who had fought the king from the beginning of the quarrel, who had raised regiments and served the Parliamentary cause in all fidelity, were discarded. They pass altogether from the story.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 256

- During the winter months the Army was reconstituted in accordance with Cromwell's ideas. The old personally raised regiments of the Parliamentary nobles were broken up ad their officers and men incorporated in entirely new formations. These, the New Model, comprised eleven regiments of horse, each six hundred strong, twelve regiments of foot, twenty-two hundred strong, and a thousand dragoons, in all twenty-two thousand men. Compulsion was freely used to fill the ranks. In one district of Sussex the three conscriptions of April, July, and September 1645 yielded a total of 149 men. A hundred and thirty-four guards were needed to escort them to the colours. At the King's headquarters it was thought that these measures would demoralise the Parliamentary troops; and no doubt at first this was so. But the Roundhead faction now had a symmetrical military organisation led by men who had risen in the field and had no other standing but their military record and religious zeal. Sir Thomas Fairfax was appointed Command-in-Chief. Cromwell, as Member for Cambridge, was at first debarred from serving. However, it soon appeared that his Self-denying Ordinance applied only to his rivals. The urgency of the new campaign and military discontents which he alone could quell forced even the reluctant Lords to make an exception in his favour. In June 1645 he was appointed General of the Horse, and was thus the only man who combined high military command with an outstanding Parliamentary position. From this moment he became the dominant figure in both spheres.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 256

- By the end of 1648 it was all over. Cromwell was Dictator. The Royalists were crushed; Parliament was a tool; the Constitution was a figment; the Scots were rebuffed, the Welsh back in their mountains; the Fleet was reorganized, London overawed. King Charles, at Carisbrooke Castle, where the donkey treads the water wheel, was left to pay the bill. It was mortal.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 274

- We must not be led by Victorian writers into regarding this triumph of the Ironsides and of Cromwell as a kind of victory for democracy and the Parliamentary system over Divine Right and Old World dreams. It was the triumph of some twenty thousand resolute, ruthless, disciplined, military fanatics over all that England has ever willed or wished. Long years and unceasing irritations were required to reverse it. Thus the struggle, in which we have in these days so much sympathy and part, begun to bring about a constitutional and limited monarchy, had led only to the autocracy of the sword. The harsh, erratic, lightning-charged being, whose erratic, opportunist, self-centred course is laid bare upon the annals, was now master, and the next twelve years are the record of his well-meant, puzzling plungings and surgings.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 274

- Above all, the conscience of man must recoil from the monster of a faction-god projected from the mind of an ambitious, interested politician on whose lips "righteousness" and "mercy" were mockery. Not even the hard pleas of necessity or the safety of the State can be invoked. Cromwell in Ireland, disposing of overwhelming strength and using it with merciless wickedness, debased the standards of human conduct and sensibly darkened the journey of mankind. Cromwell's Irish massacres find numberless compeers in the history of all countries during and since the Stone Age. It is therefore only necessary to strip men capable of such deeds of all title to honour, whether it be the light which plays around a great captain of war or the long repute which covers the severities of a successful prince or statesman.

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 291-292

- We have seen many ties which at one time or another have joined the inhabitants of the Western islands, and eve in Ireland itself offered a tolerable way of life to Protestants and Catholics alike. Upon all of these Cromwell's record as a lasting bane. By an uncompleted process of terror, by an iniquitous land settlement, by the bloody deeds already described, he cut new gulfs between the nations and the creeds. "Hell or Connaught" were the terms he thrust upon the native inhabitants, and they for their part, across three hundred years, have used as their keenest expression of hatred, "the curse of Cromwell on you." The consequences of Cromwell's rule in Ireland have distressed and at times distracted English politics even down to the present day. To heal them baffled the skill and loyalties of successive generations. They became for a time a potent obstacle to the harmony of the English-speaking peoples throughout the world. Upon all of us there still lies "the curse of Cromwell."

- Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two: The New World (1956), p. 292

His grandeur he deriv’d from heaven alone,

For he was great e’er fortune made him so

And wars like mists that rise against the sun

Made him but greater seem, not greater grow.No borrow’d bays his temple did adorn,

But to our Crown he did fresh jewels bring;

Nor was his virtue poison’d soon as born,

With the too early thoughts of being King.- John Dryden, Heroic Stanzas on the death of Oliver Cromwell, written after his funeral (1658), VI–VII

- His ashes in a peaceful urn shall rest,

His name a great example stands to show

How strangely high endeavours may be blest,

Where piety and valour jointly go.- John Dryden, Heroic Stanzas on the death of Oliver Cromwell, written after his funeral (1658), XXXVII

- He made us Freemen of the Continent,

Whom Nature did like Captives treat before,

To nobler Preys the English Lyon sent,

And taught him first in Belgian walks to roar.- John Dryden, 'An Elegy on the Usurper O.C.' (1681)

- Arguing over the legacy of Oliver Cromwell has provided fine sport for historians since the day he died. Was he a defender of English liberty? A military dictator? A genocidal maniac? A republican visionary? An uncompromising religious zealot? A perfectly willing-to-compromise religious zealot? Depending on your point of view, it’s easy to put Cromwell in a box labeled good or bad and walk away. But having gone through all of this, he turns out to be one of the more ambiguous historical leaders I’ve come across. Genuinely hesitant about amassing greater power while simultaneously amassing greater power. A devout man of God who concluded it was necessary to make way for freedom of worship. A ruthless general who took great pride in limiting the body count in his battles because he hated throwing lives away for nothing. The pacification of Ireland was obviously appalling, but Cromwell neither started that brutal process nor did he finish it. There is more than enough blame to go around on that front. He killed the king, but only after he spent years trying to figure out a way to put the king back on the throne. He dissolved or purged practically every legislative assembly he encountered, but then he just kept going back for more because maybe the next one will work out. He is portrayed as a dictator, but he kept supporting constitutions that denied anyone or anything unlimited political power. He was an obscure country gentleman who became king in all but name. And we will never stop arguing about who he really was, what he really did, or why he really did it.

- Mike Duncan, Revolutions, ep. 1.14, (2014)

- Things will shortly happen which have been unheard of, and above all would open the eyes of those who live under Kings and other Sovereigns, and lead to great changes. Cromwell alone holds the direction of political and military affairs in his hands. He is one who is worth all the others put together, and, in effect, King.

- John Dury as reported by Hermann Mylius (27 September 1651)

- Saw the superb funeral of the Protector:...but it was the joyfullest funeral that I ever saw, for there were none that cried, but dogs, which the souldiers hooted away with a barbarous noise; drinking and taking tobacco in the streets as they went.

- John Evelyn in his Diary (22 October 1658)

- This day (to the stupendous and inscrutable Judgements of God) were the Carcasses of that arch-rebell Cromwell and Bradshaw the judge who condemned his Majestie & Ireton, son-in-law to the Usurper, dragged out of their superbe tombs (in Westminster among the Kings), to Tyburn & hanged on the Gallows there from 9 in the morning til 6 at night, and then buried under that fatal and ignominious monument, in a deepe pitt: Thousands of people who (who had seen them in all their pride and pompous insults) being spectators: look back at November 22, 1658, & be astonish’d - And fear God & honour the King, but meddle not with those who are given to change.

- John Evelyn in his Diary (30 January 1661)

- Oliver Cromwell carried the reputation of England higher than it ever was at any other time.

- Henry Fielding, Amelia (1751), quoted in The Works of Henry Fielding, Esq. Vol. III, ed. Leslie Stephen (1882), p. 540

- He lived a hypocrite and died a traitor.

- John Foster

- When I came in I was moved to say, "Peace be in this house"; and I exhorted him to keep in the fear of God, that he might receive wisdom from Him, that by it he might be directed, and order all things under his hand to God's glory.

l spoke much to him of Truth, and much discourse I had with him about religion; wherein he carried himself very moderately. But he said we quarrelled with priests, whom he called ministers. I told him I did not quarrel with them, but that they quarrelled with me and my friends. "But," said I, "if we own the prophets, Christ, and the apostles, we cannot hold up such teachers, prophets, and shepherds, as the prophets, Christ, and the apostles declared against; but we must declare against them by the same power and Spirit."

Then I showed him that the prophets, Christ, and the apostles declared freely, and against them that did not declare freely; such as preached for filthy lucre, and divined for money, and preached for hire, and were covetous and greedy, that could never have enough; and that they that have the same spirit that Christ, and the prophets, and the apostles had, could not but declare against all such now, as they did then. As I spoke, he several times said, it was very good, and it was truth. I told him that all Christendom (so called) had the Scriptures, but they wanted the power and Spirit that those had who gave forth the Scriptures; and that was the reason they were not in fellowship with the Son, nor with the Father, nor with the Scriptures, nor one with another.

Many more words I had with him; but people coming in, I drew a little back. As I was turning, he caught me by the hand, and with tears in his eyes said, "Come again to my house; for if thou and I were but an hour of a day together, we should be nearer one to the other"; adding that he wished me no more ill than he did to his own soul. I told him if he did he wronged his own soul; and admonished him to hearken to God's voice, that he might stand in his counsel, and obey it; and if he did so, that would keep him from hardness of heart; but if he did not hear God's voice, his heart would be hardened. He said it was true.

Then I went out; and when Captain Drury came out after me he told me the Lord Protector had said I was at liberty, and might go whither I would.

Then I was brought into a great hall, where the Protector's gentlemen were to dine. I asked them what they brought me thither for. They said it was by the Protector's order, that I might dine with them. I bid them let the Protector know that I would not eat of his bread, nor drink of his drink. When he heard this he said, "Now I see there is a people risen that I cannot win with gifts or honours, offices or places; but all other sects and people I can." It was told him again that we had forsaken our own possessions; and were not like to look for such things from him.- George Fox, on his meeting with Cromwell, in Autobiography of George Fox (1694)

- With Cromwell's memory it has fared as with ourselves. Royalists painted him as a devil. Carlyle painted him as the masterful saint who suited his peculiar Valhalla. It is time for us to regard him as he really was, with all his physical and moral audacity, with all his tenderness and spiritual yearnings, in the world of action what Shakespeare was in the world of thought, the greatest because the most typical Englishman of all time. This, in the most enduring sense, is Cromwell's place in history. He stands there, not to be implicitly followed as a model, but to hold up a mirror to ourselves, wherein we may see alike our weakness and our strength.

- Samuel Rawson Gardiner, Cromwell's Place in History: Founded on Six Lectures Delivered in the University of Oxford (1897), pp. 115-116

- That slovenly fellow which you see before us, who hath no ornament in his speech; I say that sloven, if we should ever come to have a breech with the King (which God forbid) in such case will be one of the greatest men of England.

- John Hampden, speaking to Lord Digby in the House of Commons, as reported by Sir Richard Bulstrode

- Generally he respected, or at least pretended a love to, all ingenious persons in any arts, whom he arranged to be sent or brought to him. But the niggardliness and incompetence of his reward shewed that this man was a personated act of greatness, and that Private Cromwell yet governed Prince Oliver.

- James Heath

- His character does not appear more extraordinary and unusual by the mixture of so much absurdity with so much penetration, than by his tempering such violent ambition, and such enraged fanaticism with so much regard to justice and humanity.

- David Hume in History of England

- In a word, as he was guilty of many crimes against which Damnation is denounced, and for which hell-fire is prepared, so he had some good qualities which have caused the memory of some men in all Ages to be celebrated; and he will be look’d upon by posterity as a brave bad man.

- Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon in A History of the Rebellion

- A complex character such as that of Cromwell, is incapable of creation, except in times of great civil and religious excitement, and one cannot judge of the man without at the same time considering the contending elements by which he was surrounded. It is possible to take his character to pieces, and, selecting one or other of his qualities as a corner-stone, to build around it a monument which will show him as a patriot or a plotter, a Christian man or a hypocrite, a demon or a demi-god as the sculptor may choose.

- F.A Inderwick in The Interregnum, 1648-60

- In the common course of selfish policy, Oliver Cromwell should have cultivated the friendship of foreign powers, or at least have avoided disputes with them, the better to establish his tyranny at home. Had he been only a bad man, he would have sacrificed the honour of the nation to the success of his domestic policy. But, with all his crimes, he had the spirit of an Englishman. The conduct of such a man must always be an exception to vulgar rules. He had abilities sufficient to reconcile contradictions, and to make a great nation at the same moment unhappy and formidable.

- Junius, Letter XLIII (6 February 1771), quoted in The Letters of Junius, ed. John Cannon (1978), p. 226

- "I am," said he, "as much for a government by consent as any man; but where shall we find that consent? Amongst the Prelatical, Presbyterian, Independent, Anabaptist, or Leveling Parties?"… then he fell into the commendation of his own government, boasting of the protection and quiet which the people enjoyed under it, saying, that he was resolved to keep the nation from being imbrued in blood. I said that I was of the opinion too much blood had already been shed, unless there were a better account of it. "You do well," said he, "to charge us with the guilt of blood; but we think there is a good return for what hath been shed."

- Edmund Ludlow Interview with Cromwell (August 1656)

- The ambition of Oliver was of no vulgar kind. He never seems to have coveted despotic power. He at first fought sincerely and manfully for the Parliament, and never deserted it, till it had deserted its duty. If he dissolved it by force, it was not till he found that the few members who remained after so many deaths, secessions, and expulsions, were desirous to appropriate to themselves a power which they held only in trust, and to inflict upon England the curse of a Venetian oligarchy. But even when thus placed by violence at the head of affairs, he did not assume unlimited power. He gave the country a constitution far more perfect than any which had at that time been known in the world. He reformed the representative system in a manner which has extorted praise even from Lord Clarendon. For himself he demanded indeed the first place in the commonwealth; but with powers scarcely so great as those of a Dutch stadtholder, or an American president. He gave the Parliament a voice in the appointment of ministers, and left to it the whole legislative authority, not even reserving to himself a veto on its enactments; and he did not require that the chief magistracy should be hereditary in his family. Thus far, we think, if the circumstances of the time, and the opportunities which he had of aggrandizing himself, be fairly considered, he will not lose by comparison with Washington or Bolivar.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, 'Milton', The Edinburgh Review (August 1825), quoted in T. B. Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays, Contributed to The Edinburgh Review, Vol. I (1843), pp. 45-46

- The choice lay, not between Cromwell and liberty, but between Cromwell and the Stuarts. That Milton chose well, no man can doubt who fairly compares the events of the protectorate with those of the thirty years which succeeded it, the darkest and most disgraceful in the English annals. Cromwell was evidently laying, though in an irregular manner, the foundations of an admirable system. Never before had religious liberty and the freedom of discussion been enjoyed in a greater degree. Never had the national honour been better upheld abroad, or the seat of justice better filled at home. And it was rarely that any opposition, which stopped short of open rebellion, provoked the resentment of the liberal and magnanimous usurper. The institutions which he had established, as set down in the Instrument of Government, and the Humble Petition and Advice, were excellent.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, 'Milton', The Edinburgh Review (August 1825), quoted in T. B. Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays, Contributed to The Edinburgh Review, Vol. I (1843), pp. 46-47

- The Protector's foreign policy at the same time extorted the ungracious approbation of those who most detested him. The Cavaliers could scarcely refrain from wishing that one who had done so much to raise the fame of the nation had been a legitimate King; and the Republicans were forced to own that the tyrant suffered none but himself to wrong his country, and that, if he had robbed her of liberty, he had at least given her glory in exchange. After half a century during which England had been of scarcely more weight in European politics than Venice or Saxony, she at once became the most formidable power in the world, dictated terms of peace to the United Provinces, avenged the common injuries of Christendom on the pirates of Barbary, vanquished the Spaniards by land and sea, seized one of the finest West Indian islands, and acquired on the Flemish coast a fortress which consoled the national pride for the loss of Calais. She was supreme on the ocean. She was the head of the Protestant interest. All the reformed Churches scattered over Roman Catholic kingdoms acknowledged Cromwell as their guardian.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, Volume I [1848], ed. C. H. Firth (1913), pp. 120-122

- His body was wel compact and strong, his stature under 6 foote ( I beleeve about two inches) his head so shaped, as you might see it a storehouse and shop both of vast tresury of natural parts. His temper exceeding fyery as I have known, but the flame of it kept downe, for the most part, or soon allayed with those moral endowments he had. He was naturally compassionate towards objects in distresse, even to an effeminate measure; though God had made him a heart, wherein was left little roume for any feare, but what was due to himselfe, of which there was a large proportion, yet did he exceed in tenderness towards suffrerers. A larger soule, I thinke, hath seldom dwelt in a house of clay than his was.

- John Maidston in a letter to John Winthrop (24 March 1659)

- Of late I have not given so free and full a power unto (Cromwell) as formerly I did, because I heard that he used his power so as in honour I could not avow him in it....for his expressions were sometimes against the nobility, that he hoped to live to see never a nobleman in England, and he loved such (and such) better than others because they did not love Lords. And he further expressed himself with contempt of the Assemberly of Divines...these he termed persecutors, and that they persecuted honester men than themselves.

- Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester, Letter to the House of Lord’s (December 1644)

- So restless Cromwell could not cease

In the inglorious Arts of Peace,

But through adventrous war,

Urged his active star...

To ruine the great work of time,

And cast the kingdom old

Into another Mold...- Andrew Marvell in An Horation Ode upon Cromwell’s return from Ireland

- Cromwell, our chief of men, who through a cloud,

Not of war only, but detractions rude,

Guided by faith and matchless fortitude,

To peace and truth thy glorious way has ploughed

And on the neck of crowned fortune proud

Has reared God’s trophies, and his work pursued,

While Darwen stream with blood of Scots imbrued,

And Dunbar field resounds thy praises loud,

And Worcester’s laureate wreath. Yet much remains

To conquer still; peace hath her victories

No less renowned than war: new foes arise,

Threatening to bind our souls with secular chains:

Help us to save free conscience from the paw

Of hireling wolves whose gospel is their maw.- John Milton, Sonnet XVI, "To the Lord General Cromwell"

- The figure of Cromwell has emerged from the floating mists of time in many varied semblances, from bloodstained and hypocritical usurper up to transcendental hero and the liberator of mankind. The contradictions of his career all come over again in the fluctuations of his fame. He put a king to death, but then he broke up a parliament. He led the way in the violent suppression of bishops, he trampled on the demands of presbytery, and set up a state system of his own; yet he is the idol of voluntary congregations and the free churches. He had little comprehension of that government by discussion which is now counted the secret of liberty. No man that ever lived was less of a pattern for working those constitutional charters that are the favourite guarantees of public rights in our century. His rule was the rule of the sword. Yet his name stands first, half warrior, half saint, in the calendar of English-speaking democracy.

- John Morley, Cromwell (1900), p. 1

- I've been dreaming of a time when the English are sick to death of Labour and Tories and spit upon the name Oliver Cromwell and denounce this royal line that still salutes him and will salute him forever.

- Morrissey in the song "Irish Blood, English Heart"

- Was not Oliver's name dreadful to neighbour nations?

- Lodowicke Muggleton, A True Interpretation of all the Chief Tests, and Mysterious Sayings and Visions Opened, of the Whole Book of the Revelation of St. John (1665), quoted in The Works of John Reeve and Lodowicke Muggleton, Vol. II (1832), p. 145

- He has arrogated to himself despotic authority and the actual sovereignty of these realms under the mask of humility and the public service....Obedience and submission were never so manifest in England as at present,...their spirits are so crushed..yet...they dare not rebel and only murmur under their breath, though all live in hope of the fulfilment one day of the prophecies foretelling a change of rule ere long.

- Lorenzo Paulucci, Venetian Secretary in England, to Giovanni Sagredo, Venetian Ambassador in France, (21 February 1654)

- At dinner we talked much of Cromwell, all saying he was a brave fellow and did owe his crown he got to himself, as much as any man that ever got one.

- Samuel Pepys, Diary, (8 February 1667)

- [E]very body do now-a-days reflect upon Oliver, and commend him, what brave things he did, and made all the neighbour princes fear him.

- Samuel Pepys, diary (12 July 1667), quoted in The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Vol. VII, ed. Henry B. Wheatley (1896), p. 18

- It is Cromwell's chief merit to have ruled the British kingdoms for a succession of years on a uniform principle, and to have united their forces in common efforts. It is true that this was not the final award of history: things were yet to arrange themselves in a very different fashion. But it was necessary perhaps that the main outlines should be shaped by the absolute authority of a single will, in order that in the future a free life might develop within them.

- Leopold von Ranke, A History of England Principally in the Seventeenth Century, Vol. III (1875), p. 213

- He was a practical mystic, the most formidable and terrible of all combinations, uniting an aspiration derived from the celestial and supernatural with the energy of a mighty man of action; a great captain, but off the field seeming, like a thunderbolt, the agent of greater forces than himself; no hypocrite, but a defender of the faith; the raiser and maintainer of the Empire of England.

- Lord Rosebery as quoted in The Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell (1937) by Wilbur Cortez Abbott

- Move forward to Oliver Cromwell and you encounter an extraordinarily complex man driven by absolutely warring impulses – you could say with some truth that there was a civil war going on inside him. Here was someone to whom people were prepared to deliver power, but who obviously hated the idea of accepting office. He clearly never felt he was worthy of God's appointment. On the other hand, he was so good at doing what he did, at being a general. One half of him is a country gentleman, a political pragmatist who understands the machinery of state in a clear, Peter Mandelson-like way. But he's also – if not quite Ian Paisley – someone who at least listens to voices in his head.

- Simon Schama, 'Visions of Albion: Looking at British history', The Independent (26 September 2000)

- The beady-eyed, hard-headed men of state business wanted him to be a king they could trust. They needed a Chief Executive Officer to run Britannia Inc, the most ferocious, most heavily capitalised enterprise the world had ever seen. Then suddenly Cromwell saw the people who wanted him to do this, and saw that they were godless. When he dissolved the Rump Parliament he looked at one of its members and called him a whoremaster and drunken libertine. He was appalled that the people who were supposed to embody the sovereignty of parliament were these low-lifes, appalled to think political intelligence could be tied up with moral wretchedness. He thought he was accountable to God for having a clean England as well. But you can't have a clean England and be the CEO. It was just never going to happen.

- Simon Schama, 'Visions of Albion: Looking at British history', The Independent (26 September 2000)

- Under Cromwell the union of the three kingdoms was for the moment realised, and as the country chanced to have not only a powerful fleet but also a disciplined army and a habit of war, the new Britain took the lead of all states, and seemed on the point of succeeding to the ascendency so recently forfeited by Spain. At this moment Cromwell died, and forthwith the prospects of Britain were altered.

- John Robert Seeley, The Growth of British Policy: An Historical Essay, Volume II (1895; second edition, 1897), p. 103

- Cromwell has never had justice done him. Hume and almost all the historians have seized upon some prominent circumstances of his character, as painters and actors lay hold of the caricature to ensure a likeness. He was not always a hypocrite. Mr. Hume does not do justice to Cromwell's character in supposing him incapable of truth and simplicity on every occasion. His speeches to his Parliament give, I am persuaded, a very true picture of the times... It must be allowed that, while he had power, short as the moment was, he did set more things forward than all the Kings who reigned during the century, King William included. England was never so much respected abroad; while at home, though Cromwell could not settle the Government, talents of every kind began to show themselves, which were immediately crushed or put to sleep at the Restoration. The best and most unexceptional regulations of different kinds are to be found in his ordinances and proclamations remaining to this day unexecuted; and during his life he not only planned but enforced and executed the greatest measures of which the country was then susceptible.

- Lord Shelburne, quoted in Lord Edmond Fitzmaurice, Life of William, Earl of Shelburne, Afterwards First Marquess of Lansdowne. With Extracts from His Papers and Correspondence, Volume I. 1737–1766 (1875), pp. 22-23

- Lieutenant-General Cromwell...a member of the House of Commons, long famous for godliness and zeal to his country, of great note for his service in the House, accepted of a commission at the very beginning of this war, wherein he served his country faithfully, and it was observed God was with him, and he began to be renowned.

- Joshua Sprigge in Anglia Rediviva (1647)

- Stalin: The Communists base themselves on rich historical experience which teaches that obsolete classes do not voluntarily abandon the stage of history. Recall the history of England in the seventeenth century. Did not many say that the old social system had decayed? But did it not, nevertheless, require a Cromwell to crush it by force?

Wells: Cromwell acted on the basis of the constitution and in the name of constitutional order.

Stalin: In the name of the constitution he resorted to violence, beheaded the king, dispersed Parliament, arrested some and beheaded others!- Joseph Stalin, 'Marxism versus Liberalism: An Interview with H. G. Wells' (23 July 1934)

- It was three hundred years ago, in October 1656, that George Fox had a memorable interview with Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England. It was one of the great moments of a great century, for here, face to face, were two of the most powerful personalities of the age, the one the military dictator of the British Isles at the pinnacle of his worldly power, the other a crude, rustic preacher who had just spent eight months in one of England's foulest prisons. They met in Whitehall, at the very heart of the British government. Fox bluntly took the Protector to task for persecuting Friends when he should have protected them. Then characteristically he set about trying to make a Quaker out of Cromwell, to turn him to "the light of Christ who had enlightened every man that cometh into the world." Cromwell was in an argumentative mood and took issue with Fox's theology, but Fox had no patience with his objections. "The power of God riz in me," he wrote, "and I was moved to bid him lay down his crown at the feet of Jesus."

Cromwell knew what Fox meant, for two years earlier he had received a strange and disturbing missive in which he had read these words:

- God is my witness, by whom I am moved to give this forth for the Truth's sake, from him whom the world calls George Fox; who is the son of God who is sent to stand a witness against all violence and against all the works of darkness, and to turn people from the darkness to the light, and to bring them from the occasion of the war and from the occasion of the magistrate's sword...

- The man who persisted in calling himself the "son of God"— he later acknowledged that he had many brothers — was demanding nothing less than that the military ruler of all England should forthwith disavow all violence and all coercion, make Christ's law of love the supreme law of the land, and substitute the mild dictates of the Sermon on the Mount for the Instrument of Government by which he ruled. In a word, Fox would have him make England a kind of pilot project for the Kingdom of Heaven. Fox was a revolutionary. He had no patience with the relativities and compromises of political life. His testimony was an uncompromising testimony for the radical Christian ethic of love and non-violence, and he would apply it in the arena of politics as in every other sphere of life. It is not recorded that Cromwell took his advice.

- Frederick B. Tolles, in his address "Quakerism and Politics" (9 November 1956)

- As for that famous and magnanimous commander, Lieutenant-General Cromwell, whose prowess and prudence, as they have rendered him most renowned for many former successful deeds of chivalry, so in this fight they have crowned him with the never withering laurels of fame and honour, who with so lion-like courage and impregnable animosity, charged his proudest adversaries again and again, like a Roman Marcellus indeed....and at last came off, as with some wounds, so with honour and triumph inferior to none.

- John Vicars, Magnalia Dei Anglicana Or England’s Parliamentary-Chronicle (1646)

- Our dying-Hero, from the Continent,

Ravish't whole Towns; and Forts, from Spaniards rest,

As his last Legacy, to Brittain lest.

The Ocean which so long our hopes confin'd

Could give no limits to His vaster mind;

Our Bounds inlargment was his latest toyle;

Nor hath he left us Prisoners to our Isle;

Under the Tropick is our language spoke,

And part of Flanders hath receiv'd our yoke.

From Civill Broyls he did us disingage,

Found nobler objects for our Martiall rage;

And with wise Conduct to his Country show'd

Their ancient way of conquering abroad:

Ungratefull then, if we no Tears allow

To Him that gave us Peace, and Empire too.- Edmund Waller, 'To the Happie Memory of the most Renowned Prince, Oliver Lord Protector, &c. Pindarick Ode.', Three poems upon the death of His late Highnesse Oliver lord protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland written by Mr Edm. Waller, Mr Jo. Dryden, Mr Sprat of Oxford (1659), p. 31

- Whilst he was curious of his own words, (not putting forth too many lest they should betray his thoughts) he made others talk until he had, as it were, sifted them, and known their most intimate designs.

- Sir William Waller in Recollections

- I... had occasion to converse with Mr Cromwell’s physician, Dr Simcott, who assured me that for many years his patient was a most splenetick man and had phansies about the cross in that town; and that he had been called up to him at midnight, and such unseasonable hours very many times, upon a strong phansy, which made him belive he was then dying; and there went a story of him, that in the day-time, lying melancholy in his bed, he belived the spirit appeared to him, and told him he should be the greatest man, (not mentioning the word King) in this Kingdom. Which his uncle, Sir Thomas Steward, who left him all the little estate Cromwell had, told him was traiterous to relate.

- Sir Philip Warwick in Memoirs of Sir Philip Warwick

- I came into the House one morning, well clad, and perceived a gentleman speaking whom I knew not, very ordinarily apparelled, for it was a plain cloth suit, which seemed to have been made by an ill country tailor. His linen was plain, and not very clean; and I remember a speck or two of blood upon his little band which was not much larger than his collar. His hat was without a hat-band. His stature was of a good size; his sword stuck close to his side; his countenance swoln and reddish; his voice sharp and untuneable, and his eloquence full of fervor.

- Sir Philip Warwick, as quoted by John Richard Green in his book History of the English People, Volume III: Puritan England 1603-1660, The Revolution 1660-1688 (1882), p. 232

- As to your own person the title of King would be of no advantage, because you have the full Kingly power in you already... I apprehend indeed, less envy and danger, and pomp, but not less power, and real opportunities of doing good in your being General than would be if you had assumed the title of King.

- Bulstrode Whitelocke to Cromwell as reported in Whitelocke's Memorialls of English Affairs

- He would sometimes be very cheerful with us, and laying aside his greatness he would be exceeding familiar with us, and by way of diversion would make verses with us, and everyone must try his fancy. He commonly called for tobacco, pipes, and a candle, and would now and then take tobacco himself; then he would fall again to his serious and great business.

- Bulstrode Whitelocke in Memorialls of English Affairs

- In short, every beast hath some evil properties; but Cromwell hath the properties of all evil beasts.

- Archbishop John Williams to King Charles at Oxford, as quoted in Life of Archbishop Williams by Hackett

- The English monster, the center of mischief, a shame to the British Chronicle, a pattern for tyranny, murder and hypocrisie, whose bloody Tyranny will quite drown the name of Nero, Caligula, Domitian, having at last attained the height of his Ambition, for Five years space he wallowed in the blood of many Gallant and Heroick Persons.

- William Winstanley, Loyal Martyrology as quoted in Conflicts with Oblivion (1935) by Wilbur Cortez Abbott, p. 159

- The mettle and superiour genius of Cromwell subdued faction and rebellion, by the very power they had put into their hands against the lawful sovereign. He supported his state and terrified all Europe, as well as the three nations, by the grandeur of his courage, and the spirit of his army; which he made, in effect, his parliament.

- Charles Wogan to Jonathan Swift (7 February 1732–3), quoted in The Works of the Rev. Jonathan Swift, Volume 19 (1733), p. 107

- The Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and of the Dominions thereunto belonging, shall be and reside in one person, and the people assembled in parliament; the style of which person shall be "The Lord Protector of the Commonwealth"… That Oliver Cromwell, Captain General of the forces of England, Scotland and Ireland, shall be, and is hereby declared to be, Lord Protector...for his life.

- Decree by the Instrument of Government (16 December 1653)

External links

[edit]- Cromwell Association

- Cromwell biography at Britannia.com

- Cromwell biography at Internet Modern History Source Book

- Cromwell biography at British Civil Wars

- Brief biography at the Victoria Web

- Military related Oliver Cromwell quotes