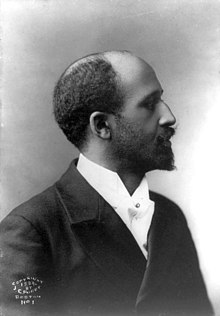

W. E. B. Du Bois

Appearance

(Redirected from W. E. B. Dubois)

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (23 February 1868 – 27 August 1963) was an American civil rights activist, sociologist, educator, historian, author, editor, and scholar.

Quotes

[edit]

- There is always a certain glamour about the idea of a nation rising up to crush an evil simply because it is wrong. Unfortunately, this can seldom be realized in real life; for the very existence of the evil usually argues a moral weakness in the very place where extraordinary moral strength is called for.

- There is but one coward on earth, and that is the coward that dare not know.

- The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.

- To the Nations of the World, address to Pan-African conference, London (1900). These words are also found in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), ch. II: Of the Dawn of Freedom

- I insist that the object of all true education is not to make men carpenters, it is to make carpenters men.

- The Talented Tenth, published as the second chapter of The Negro Problem, a collection of articles by African Americans (New York: James Pott and Company, 1903)

- The school system in the country districts of the South is a disgrace and in few towns and cities are Negro schools what they ought to be. We want the national government to step in and wipe out illiteracy in the South. Either the United States will destroy ignorance or ignorance will destroy the United States.

And when we call for education we mean real education. We believe in work. We ourselves are workers, but work is not necessarily education. Education is the development of power and ideal. We want our children trained as intelligent human beings should be, and we will fight for all time against any proposal to educate black boys and girls simply as servants and underlings, or simply for the use of other people. They have a right to know, to think, to aspire.

These are some of the chief things which we want. How shall we get them? By voting where we may vote, by persistent, unceasing agitation; by hammering at the truth, by sacrifice and work.

We do not believe in violence, neither in the despised violence of the raid nor the lauded violence of the soldier, nor the barbarous violence of the mob, but we do believe in John Brown, in that incarnate spirit of justice, that hatred of a lie, that willingness to sacrifice money, reputation, and life itself on the altar of right. And here on the scene of John Brown’s martyrdom we reconsecrate ourselves, our honor, our property to the final emancipation of the race which John Brown died to make free.

Our enemies, triumphant for the present, are fighting the stars in their courses. Justice and humanity must prevail.

- The cost of liberty is less than the price of repression.

- John Brown: A Biography (1909): "The Legacy of John Brown"

- Liberty trains for liberty. Responsibility is the first step in responsibility.

- John Brown: A Biography (1909): "The Legacy of John Brown"

- I believe that there are human stocks with whom it is physically unwise to intermarry, but to think that these stocks are all colored or that there are no such white stocks is unscientific and false.

- As quoted in Fighting Fire with Fire: African Americans and Hereditarian Thinking, 1900-1942 by Gregory Michael Dorr (RTF document). Dorr dates this quote to 1910.

- I do not laugh. I am quite straight-faced as I ask soberly:

"But what on earth is whiteness that one should so desire it?" Then always, somehow, some way, silently but clearly, I am given to understand that whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!

Now what is the effect on a man or a nation when it comes passionately to believe such an extraordinary dictum as this? That nations are coming to believe it is manifest daily. Wave on wave, each with increasing virulence, is dashing this new religion of whiteness on the shores of our time. Its first effects are funny: the strut of the Southerner, the arrogance of the Englishman amuck, the whoop of the hoodlum who vicariously leads your mob.- Darkwater (1920), Ch. II: The Souls of White Folk

- The cause of war is preparation for war.

- Darkwater (1920), Ch. II: The Souls of White Folk

- It is ridiculous to seek to excuse Robert Lee as the most formidable agency this nation ever raised to make 4 million human beings goods instead of men. Either he knew what slavery meant when he helped maim and murder thousands in its defense, or he did not. If he did not he was a fool. If he did, Robert Lee was a traitor and a rebel–not indeed to his country, but to humanity and humanity’s God.

- Essay on Robert E. Lee (1928)

- Hitler set up a tyranny: a state with a mighty police force, a growing army, a host of spies and informers, a secret espionage, backed by swift and cruel punishment, which migh vary from loss of job to imprisonment, incommunicado and without trial, to cold murder.

- The Hitler State, Writing on National Socialism, Pittsburgh Courier, December 12, 1936. Republished in Aptheker, Herbert, ed (1986). Newspaper Columns: 1883-1944. Kraus-Thomson Organization. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-527-25347-9.

- There has been no tragedy in modern times equal in its awful effects to the fight on the Jew in Germany. It is an attack on civilization, comparable only to such horrors as the Spanish Inquisition and the African slave trade. It has set civilization back a hundred years, and in particular has it made the settlement and understanding of race problems more difficult and more doubtful. It is widely believed by many that the Jewish problem in Germany was episodic, and is already passing. Visitor to the Olympic Games are apt to have gotten that impression. They saw no Jewish oppression. Just as Northern visitors to Mississippi see no Negro oppression.

- The Present Plight of The German Jew, Writing on National Socialism, Pittsburgh Courier, December 19, 1936. Republished in Aptheker, Herbert, ed (1986). Newspaper Columns: 1883-1944. Kraus-Thomson Organization. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-527-25347-9.

- By sheer will and grit, arising out of this, amid the derision and disdain of the world, Hitler has become the greatest figure of the Twentieth Century and in all probability will be the arbiter of the future patterns of human civilization.

- "As the Crow Flies," New York Amsterdam News, June 1, 1940. Republished in Aptheker, Herbert, ed (1986). Newspaper Columns: 1883-1944. Kraus-Thomson Organization. ISBN 978-0-527-25347-9.

- Joseph Stalin was a great man; few other men of the 20th century approach his stature. He was simple, calm and courageous. He seldom lost his poise; pondered his problems slowly, made his decisions clearly and firmly; never yielded to ostentation nor coyly refrained from holding his rightful place with dignity. He was the son of a serf but stood calmly before the great without hesitation or nerves. But also — and this was the highest proof of his greatness — he knew the common man, felt his problems, followed his fate.

- How shall Integrity face Oppression? What shall Honesty do in the face of Deception, Decency in the face of Insult, Self-Defense before Blows? How shall Desert and Accomplishment meet Despising, Detraction, and Lies? What shall Virtue do to meet Brute Force? There are so many answers and so contradictory; and such differences for those on the one hand who meet questions similar to this once a year or once a decade, and those who face them hourly and daily.

- The Ordeal of Mansart (1957) [Kraus-Thomson, 1976, ISBN 0-527-25270-0], p. 275

- The return from your work must be the satisfaction which that work brings you and the world's need of that work. With this, life is heaven, or as near heaven as you can get. Without this — with work which you despise, which bores you, and which the world does not need — this life is hell.

- To His Newborn Great-Grandson, address on his ninetieth birthday (1958)

- In my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger.

- Believe in life! Always human beings will progress to greater, broader, and fuller life.

- Last message to the world (written 1957); read at his funeral (1963)

- The most ordinary Negro is a distinct gentleman, but it takes extraordinary training and opportunity to make the average white man anything but a hog.

- Interview with Ralph McGill, quoted in The Atlantic Monthly (November 1965)

- The Soviet Union does not allow any church of any kind to interfere with education, and religion is not taught in public schools. It seems to me that this is the greatest gift of the Russian Revolution to the modern world. Most educated modern men no longer believe in religious dogma. If questioned they will usually resort to double-talk before admitting the fact. But who today actually believes that this world is ruled and directed by a benevolent person of great power who, on humble appeal, will change the course of events at our request? Who believes in miracles? Many folk follow religious ceremonies and services and allow their children to learn fairy tales and so-called religious truth, which in time the children come to recognize as conventional lies told by their parents and teachers for the children's good. One can hardly exaggerate the moral disaster of the custom. We have to thank the Soviet Union for the courage to stop it.

- The Autobiography of W.E. Burghardt Du Bois (1968), Ch. IV : The Soviet Union; he later states in Ch. XVI : My Character: "I think the greatest gift of the Soviet Union to modern civilization was the dethronement of the clergy and the refusal to let religion be taught in the public schools."

- The men of the Niagara Movement coming from the toil of the year's hard work and pausing a moment from the earning of their daily bread turn toward the nation and again ask in the name of ten million the privilege of a hearing. In the last year the work of the Negro hater has flourished in the land. Step by step the defenders of the rights of American citizens have retreated. The work of stealing the black man's ballot has progressed and the fifty and more representatives of stolen votes still sit in the nation's capital. Discrimination in travel and public accommodation has so spread the some of our weaker brethren are actually afraid to thunder against color discrimination as such and are simply whispering for ordinary decencies.

- The Niagara Movement, Address to the Country

The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

[edit]

- After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, — a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two warring souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.

- Ch. I: Of Our Spiritual Strivings

- To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.

- Ch. I: Of Our Spiritual Strivings

- And yet this very singleness of vision and thorough oneness with his age is a mark of the successful man. It is as though Nature needs must make men narrow in order to give them force.

- Ch. III: Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others

- The function of the university is not simply to teach bread-winning, or to furnish teachers for the public schools or to be a centre of polite society; it is, above all, to be the organ of that fine adjustment between real life and the growing knowledge of life, an adjustment which forms the secret of civilization.

- Ch. V: Of the Wings of Atalanta

- The worker must work for the glory of his handiwork, not simply for pay; the thinker must think for truth, not for fame.

- Ch. V: Of the Wings of Atalanta

- I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color-line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of the evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Philistine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land?

- Ch. VI: Of the Training of Black Men

- It is, then, the strife of all honorable men and women of the twentieth century to see that in the future competition of the races the survival of the fittest shall mean the triumph of the good, the beautiful, and the true; that we may be able to preserve for future civilization all that is really fine and noble and strong, and not continue to put a premium on greed and imprudence and cruelty.

- Ch. IX: Of the Sons of Master and Man

- Daily the Negro is coming more and more to look upon law and justice, not as protecting safeguards, but as sources of humiliation and oppression. The laws are made by men who have little interest in him; they are executed by men who have absolutely no motive for treating the black people with courtesy and consideration; and, finally, the accused law-breaker is tried, not by his peers, but too often by men who would rather punish ten innocent Negroes than let one guilty one escape.

- Ch. IX: Of the Sons of Master and Man

- The Negro cannot stand the present reactionary tendencies and unreasoning drawing of the color line indefinitely without discouragement and retrogression. And the condition of the Negro is ever the cause for further discrimination.

- Ch. IX: Of the Sons of Master and Man

- Why was his hair tinted with gold? An evil omen was golden hair in my life. Why had not the brown of his eyes crushed out and killed the blue? — for brown were his father’s eyes, and his father’s father’s. And thus in the Land of the Color-line I saw, as it fell across my baby, the shadow of the Veil.

- Ch. XI: Of the Passing of the First-Born

- Within the Veil was he born, said I; and there within shall he live, — a Negro and a Negro's son. Holding in that little head — ah, bitterly! — the unbowed pride of a hunted race, clinging with that tiny dimpled hand — ah, wearily! — to a hope not hopeless but unhopeful, and seeing with those bright wondering eyes that peer into my soul a land whose freedom is to us a mockery and whose liberty is a lie.

- Ch. XI: Of the Passing of the First-Born

- Herein lies the tragedy of the age: not that men are poor, — all men know something of poverty; not that men are wicked, — who is good? not that men are ignorant, — what is Truth? Nay, but that men know so little of men.

- Ch. XII: Of Alexander Crummell

- It was a bright September afternoon, and the streets of New York were brilliant with moving men.... He was pushed toward the ticket-office with the others, and felt in his pocket for the new five-dollar bill he had hoarded.... When at last he realized that he had paid five dollars to enter he knew not what, he stood stock-still amazed.... John... sat in a half-maze minding the scene about him; the delicate beauty of the hall, the faint perfume, the moving myriad of men, the rich clothing and low hum of talking seemed all a part of a world so different from his, so strangely more beautiful than anything he had known, that he sat in dreamland, and started when, after a hush, rose high and clear the music of Lohengrin's swan. The infinite beauty of the wail lingered and swept through every muscle of his frame, and put it all a-tune. He closed his eyes and grasped the elbows of the chair, touching unwittingly the lady's arm. And the lady drew away. A deep longing swelled in all his heart to rise with that clear music out of the dirt and dust of that low life that held him prisoned and befouled. If he could only live up in the free air where birds sang and setting suns had no touch of blood! Who had called him to be the slave and butt of all?... If he but had some master-work, some life-service, hard, aye, bitter hard, but without the cringing and sickening servility.... When at last a soft sorrow crept across the violins, there came to him the vision of a far-off home — the great eyes of his sister, and the dark drawn face of his mother.... It left John sitting so silent and rapt that he did not for some time notice the usher tapping him lightly on the shoulder and saying politely, 'will you step this way please sir?'... The manager was sorry, very very sorry — but he explained that some mistake had been made in selling the gentleman a seat already disposed of; he would refund the money, of course... before he had finished John was gone, walking hurriedly across the square... and as he passed the park he buttoned his coat and said, 'John Jones you're a natural-born fool.' Then he went to his lodgings and wrote a letter, and tore it up; he wrote another, and threw it in the fire....

- Ch. XIII: Of the Coming of John

The Negro (1915)

[edit]

- Present-day students are often puzzled at the apparent contradictions of Southern slavery. One hears, on the one hand, of the staid and gentle patriarchy, the wide and sleepy plantations with lord and retainers, ease and happiness; on the other hand one hears of barbarous cruelty and unbridled power and wide oppression of men. Which is the true picture? The answer is simple: both are true. They are not opposite sides of the same shield; they are different shields.

- Ch. XI: The Negro in the United States

- The theory of democratic government is not that the will of the people is always right, but rather that normal human beings of average intelligence will, if given a chance, learn the right and best course by bitter experience.

- Ch. XI: The Negro in the United States

- Unfortunately there was one thing that the white South feared more than Negro dishonesty, ignorance, and incompetency, and that was Negro honesty, knowledge, and efficiency.

- Ch. XI: The Negro in the United States

Black Reconstruction in America (1935)

[edit]- The object of this new American industrial empire, so far as that object was conscious and normative, was not national well-being, but the individual gain of the associated and corporate monarchs through the power of vast profit on enormous capital investment; through the efficiency of an industrial machine that bought the highest managerial and engineering talent and used the latest and most effective methods and machines in a field of unequaled raw material and endless market demand. That this machine might use the profit for the general weal was possible and in cases true. But the uplift and well-being of the mass of men, of the cohorts of common labor, was not its ideal or excuse. Profit, income, uncontrolled power in My Business for My Property and for Me—this was the aim and method of the new monarchial dictatorship that displaced democracy in the United States in 1876.

- p. 586

- So far as the Negroes were concerned, their demand for a reasonable part of the land on which they had worked for a quarter of a millennium was absolutely justified, and to give them anything less than this was an economic farce.

- p. 602

- To have given each one of the million Negro free families a forty-acre freehold would have made a basis of real democracy in the United States that might easily have transformed the modern world.

- p. 602

- The Sherman order gave rise to all sorts of difficulties. The Negroes were given only possessory titles. Then the owners came back and immediately there was trouble. The Negroes protested, “What is the use of giving us freedom if we can’t stay where we were raised and own our own house where we were born and our own piece of ground?” It was on May 25, 1865, that Johnson in his Proclamation of Pardon had provided easy means whereby all property could be restored, except the land at Port Royal, which had been sold for taxes. General Howard came to Charleston to make arrangements, and the story is characteristic—“At first,” said a witness, “the people hesitated, but soon as the meaning struck them that they must give up their little homes and gardens and work for others, there was a general murmuring of dissatisfaction.”

- p. 602

- President Johnson, forgetting his own pre-war declaration that the “great plantations must be seized, and divided into small farms,” declared that this land must be restored to its original owners and this would be done if owners received a presidential pardon. The pardoning power was pushed and the land all over the South rapidly restored. Negroes were dispossessed.

- p. 603

- The first attempt of a democracy which includes the previously disfranchised poor is to redistribute wealth and income, and this is exactly what the black South attempted. The theory is that the wealth and the current income of the wealthy ruling class does not belong to them entirely, but is the product of the work and striving of the great millions; and that, therefore, these millions ought to have a voice in its more equitable distribution; and if this is true in modern countries, like France and England and Germany, how much more true was it in the South after the war where the poorest class represented the most extreme case of theft of labor that the world can conceive; namely, chattel slavery?

- p. 604

- The Negro voter ... had, then, but one clear economic ideal and that was his demand for land, his demand that the great plantations be subdivided and given to him as his right. This was a perfectly fair and natural demand and ought to have been an integral part of Emancipation. To emancipate four million laborers whose labor had been owned, and separate them from the land upon which they had worked for nearly two and a half centuries, was an operation such as no modern country had for a moment attempted or contemplated. The German and English and French serf, the Italian and Russian serf, were, on emancipation, given definite rights in the land. Only the American Negro slave was emancipated without such rights and in the end this spelled for him the continuation of slavery.

- p. 611

- The treatment of the period of Reconstruction reflects small credit upon American historians as scientists. We have too often a deliberate attempt so to change the facts of history that the story will make pleasant reading for Americans.

- p. 713

- The difference of development, North and South, is explained as a sort of working out of cosmic social and economic law. ... In this sweeping mechanistic interpretation, there is no room for the real plot of the story, for the clear mistake and guilt of building a new slavery of the working class in the midst of a fateful experiment in democracy.

- pp. 714-715

- The most magnificent drama in the last thousand years of human history is the transportation of ten million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent into the new-found Eldorado of the West. They descended into Hell; and in the third century they arose from the dead, in the finest effort to achieve democracy for the working millions which this world had ever seen. It was a tragedy that beggared the Greek; it was an upheaval of humanity like the Reformation and the French Revolution. Yet we are blind and led by the blind. We discern in it no part of our labor movement; no part of our industrial triumph; no part of our religious experience. Before the dumb eyes of ten generations of ten million children, it is made mockery of and spit upon; a degradation of the eternal mother; a sneer at human effort; with aspiration and art deliberately and elaborately distorted. And why? Because in a day when the human mind aspired to a science of human action, a history and psychology of the mighty effort of the mightiest century, we fell under the leadership of those who would compromise with truth in the past in order to make peace in the present and guide policy in the future.

- p. 727

The Wisdom of W.E.B. Du Bois (2003)

[edit]- A compendium of quotations from Du Bois's writings, edited by Aberjhani, to commemorate the centennial of the publication of The Souls of Black Folk.

- I am one who tells the truth and exposes evil and seeks with Beauty for Beauty to set the world right.

- p. xi

- Human nature is not simple and any classification that roughly divides men into good and bad, superior and inferior, slave and free, is and must be ludicrously untrue and universally dangerous as a permanent exhaustive classification.

- p. 10

- The world is shrinking together; it is finding itself neighbor to itself in strange, almost magic degree.

- p. 11

- The time must come when, great and pressing as change and betterment may be, they do not involve killing and hurting people.

- p. 74

- The cause of war is preparation for war.

- p. 75

- The Negro slave trade was the first step in modern world commerce, followed by the modern theory of colonial expansion. Slaves as an article of commerce were shipped as long as the traffic paid.

- p. 104

- I believe in God who made of one blood all races that dwell on earth. I believe that all men, black and brown and white, are brothers, varying through Time and Opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and in the possibility of infinite development.

- p. 132

Quotes about Du Bois

[edit]- He was at once a scientist in his skillful use of history as a tool for comprehending the present, and a prophet in the application of his gift for analyzing the present as an indicator of the future. Because he lived simultaneously firmly entrenched within his time and decades ahead of it, the light of his wisdom, like that of his great love for humanity, is one that never diminishes.

- Aberjhani, in The Wisdom of W.E.B. Du Bois (2003), p. xvi

External links

[edit]- W. E. B. Du Bois in New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Works by W. E. B. Du Bois at Project Gutenberg

- Poems by W. E. B. Du Bois at PoetryFoundation.org

- Online articles by Du Bois

- W. E. B. Du Bois: Online Resources, from the Library of Congress

- W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African American Research

- Exhibition at University of Massachusetts Amherst

- W. E. B. Du Bois National Historic Site

Categories:

- 1868 births

- 1963 deaths

- Civil rights activists

- Activists from the United States

- Economists from the United States

- Historians from the United States

- Sociologists from the United States

- Philosophers from the United States

- Educators from the United States

- Academics from the United States

- Editors from the United States

- Non-fiction authors from the United States

- People from Massachusetts

- Agnostics from the United States

- African American communists

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- Harvard University alumni

- Pan-Africanists

- Lenin Peace Prize recipients