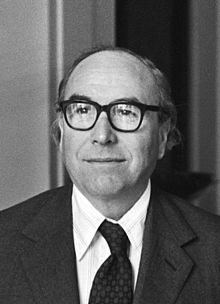

Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead OM PC (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician who served as the sixth president of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981, having previously been one of the primary proponents of British entry into the European Economic Community. At various times a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Labour Party, Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Liberal Democrats, he was Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary under the Wilson and Callaghan Governments. He initially identified as a democratic socialist, and later as a social democrat and centrist. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, he pursued a tight fiscal policy to control the inflation of the pound sterling. As Home Secretary, he was responsible for abolishing capital punishment and decriminalizing abortion, homosexuality, and divorce. He ran in the 1976 Labour Party leadership election to become Prime Minister, but was defeated by James Callaghan and briefly retired from British politics to serve as President of the European Commission. He returned to Britain to help found the Social Democratic Party, which formed an alliance with the Liberal Party under David Steel and was intended as a centrist alternative to the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher and the Labour Party under Michael Foot. However, he resigned as Party Leader after the SDP-Liberal Alliance failed to outpoll the Labour Party in the 1983 general election.

Quotes

[edit]1940s

[edit]- It was better to have a somewhat harsh Budget, which would cure inflation, rather than a generous, popular Budget which would merely undermine the purchasing power of the pound.

- Maiden speech in the House of Commons (3 June 1948)

1950s

[edit]- Future nationalisations will be more concerned with equality than with planning, and this means that we can leave the monolithic public corporation behind us and look for more intimate forms of ownership and control.

- Fair Shares for the Rich (Tribune, 1951), p. 16

- Neutrality is essentially a conservative policy, a policy of defeat, of announcing to the world that we have nothing to say to which the world will listen. ... Neutrality could never be acceptable to anyone who believes that he has a universal faith to preach. And those countries which have successfully adopted it in the past have paid the price of becoming little islands full of frustrated hedonists. Switzerland and Sweden are as ideologically sterile as they are physically undevastated.

- Pursuit of Progress (Heinemann, 1953), pp. 44–45

- It is quite impossible to advocate both the abolition of great inequalities of wealth and the acceptance of a one-quarter public sector and three-quarters private sector arrangement. A mixed economy there will undoubtedly be, certainly for many decades and perhaps permanently, but it will need to be mixed in very different proportions from this.

- Pursuit of Progress (Heinemann, 1953), p. 96

- The first duty of a party of the left is to be radical in the context of the moment, to offer the prospect of continuing advance, and to preserve the loyalty of those whose optimistic humanism makes them its natural supporters.

- Pursuit of Progress (Heinemann, 1953), p. 161

- Representative democracy demands a clear division of function between the electors and the elected. The former choose their representatives and retain the essential right of sacking them, if they are not satisfied with their work, at the end of a fixed period. But in the meantime the elected representatives, whether they are members of Parliament or city councillors, should be given full freedom to do their jobs. Any form of referendum is an infringement of this freedom, and the more complex and detailed the issue upon which it is held the more absurd an infringement it becomes.

- Letter to The Times with Henry Usborne (22 January 1954), p. 7

- It is hard to understand why an attempt to get more of the national product for those who at present get least is to be dismissed as pandering to envy, while an attempt to tilt it the other way by securing more concessions for the discontented Conservative electors of Tonbridge is not denounced as rapacity, and why the one is manifestly more worthy than the other.

- Letter to The Times (23 July 1956), p. 9

- The chief danger for a country placed as we are is that of living sullenly in the past, of believing that the world has a duty to keep us in the station to which we are accustomed, and showing bitter resentment if it does not do so. This was the mood of Suez; and it is a mood absolutely guaranteed, not to recreate our past glories, but to reduce us to a level of influence and wealth far lower than that which we need occupy. ... Our neighbours in Europe are roughly our economic and military equals. We would do better to live gracefully with them than to waste our substance by trying unsuccessfully to keep up with the power giants of the modern world.

- The Labour Case (Penguin, 1959), p. 11

- Suez was a totally unsuccessful attempt to achieve unreasonable and undesirable objectives by methods which were at once reckless and immoral; and the consequences, as was well deserved, were humiliating and disastrous.

- The Labour Case (Penguin, 1959), p. 14

- Let us be on the side of those who want people to be free to live their own lives, to make their own mistakes, and to decide, in an adult way and provided they do not infringe the rights of others, the code by which they wish to live; and on the side of experiment and brightness, of better buildings and better food, of better music (jazz as well as Bach) and better books, of fuller lives and greater freedom. In the long run these things will be more important than the most perfect of economic policies.

- The Labour Case (Penguin, 1959), p. 146

1960s

[edit]- There is also the point, put by my hon. Friend the Member for Grimsby yesterday, that if we are to devote absolute priority constantly to shrinking the total of public expenditure as a proportion of our national income, what sort of community are we to live in? Do hon. Members opposite really want to see, in Professor Galbraith's striking phrase, "Public squalor in the midst of private affluence", as the future for this country? Let hon. Members make no mistake about it: that is what this involves, and our hospital, education and public services will become even more inadequate than they are at present if we devote our attention primarily and exclusively to the task of shrinking the proportion of public expenditure.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 April 1960)

- We exist to change society. We are not likely to be very successful if we are horrified at any suggestion of changing ourselves. One of the things from which we are suffering is a misplaced national complacency: a belief that we do things better than anyone else. Do not let us be too afraid, as a Labour Party, of learning from some of our friends abroad. Parties all over the world have been modernizing themselves. There are only two unreconstructed socialist parties in the world—the French and the Australian. Do not let us be too conservative, complacent, and insular.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Scarborough (6 October 1960) in favour of revising Clause IV, quoted in The Times (7 October 1960), p. 20

- I am myself convinced that the existing law on abortion is uncertain and is also, and perhaps more importantly, harsh and archaic and that it is in urgent need of reform. I certainly shall have no hesitation in voting for the Second Reading of the Bill. I take this view because I believe that we have here a major social problem. How can anyone believe otherwise when perhaps as many as 100,000 illegal operations a year take place, that the present law has shown itself quite unable to deal with the problem? I believe this, too, because of the danger which exists at present to those who are forced to resort to back-street abortionists and to the misery which is caused to some of those who fail to get an abortion. I believe it also because we all know...that the law is consistently flouted by those who have the means to do so. It is, therefore, very much a question of one law for the rich and one law for the poor.

- It would be a mistake to think...that by what we are doing tonight we are giving a vote of confidence or congratulation to homosexuality. Those who suffer from this disability carry a great weight of loneliness, guilt and shame. The crucial question, which we are nearly at the end of answering decisively, is, should we add to those disadvantages the full rigour of the criminal law? By its overwhelming decisions, the House has given a fairly clear answer, and I hope that the Bill will now make rapid progress towards the Statute Book. It will be an important and civilising Measure.

- No one contemplating the present position and looking back at the whole series of vicissitudes which has beset the British economy throughout the past 20 years can find the prospect other than very difficult at present. But I believe that there is also a great opportunity at present. There is certainly no quick, easy road to prosperity for this country, but the changes which must be made are fairly marginal. They must be made with absolute determination, but if they are so made, and accepted by the people, the whole outlook can change. The Government can only provide the right framework. Unless they do that, our national energies will be misdirected, but once they have done it the opportunities for export and growth and efficiency must be seized by everyone. There will still be two years of hard slog ahead. But at the end of it we could have a more securely-based prosperity than we have known for a generation.

- Speech in the House of Commons as Chancellor of the Exchequer (17 January 1968)

- It is not some malevolent quirk of international bankers which makes the balance of payments surplus necessary. It is the hard facts of life. Quite a few of the resolutions mention the need to get rid of the shackles of international finance. These shackles can be exaggerated. If you want less to do with bankers and fewer International Monetary Fund visits the answer is straightforward: Help us to get out of debt. It is no good urging independence and denying policies to that end.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Blackpool (30 September 1968), quoted in The Times (1 October 1968), p. 6

- In these circumstances it is essential we should be able to speak with sanity and authority in world monetary affairs. You cannot do this from a position of perpetual deficit.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Blackpool (30 September 1968), quoted in The Times (1 October 1968), p. 6

- [The "permissive society" had been allowed to become a dirty phrase.] A better phrase is the 'civilized society', based on the belief that different individuals will wish to make different decisions about their patterns of behaviour and that, provided these do not restrict the freedom of others, they should be allowed to do so within a framework of understanding and tolerance. ... And the idea that our moderate progress towards giving the individual greater freedom from the law in matters of social conduct is responsible for the troubles of modern society is plain nonsense.

- Speech in Abingdon, Berkshire (19 July 1969), quoted in The Times (21 July 1969), p. 3

- One of the central purposes of democratic socialism was to extend throughout the community the opportunity of freedom of choice which used to be the prerogative of the few.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference in Brighton (1 October 1969), quoted in The Times (2 October 1969), p. 1

1970s

[edit]- Three years ago it [public opinion] was strongly in favour of entry [into the EEC]. It may change again...and in any case I do not believe that it is always the duty of those who seek to lead to follow public opinion.

- Speech in Birmingham (18 June 1971), quoted in The Times (19 June 1971), p. 1

- At conference the only alternative [to the EEC] we heard was 'socialism in one country'. That is always good for a cheer. Pull up the drawbridge and revolutionize the fortress. That's not a policy either: it's just a slogan, and it is one which becomes not merely unconvincing but hypocritical as well when it is dressed up as our best contribution to international socialism.

- Speech to the Parliamentary Labour Party (19 July 1971), quoted in The Times (20 July 1971), p. 4

- In spite of half a century of effort, our society—and still more our world—is still disfigured by gross unfairness. ... Concern is indivisible and so is selfishness. A society which says 'to hell with famine and disease in Bangladesh, it's all their own fault, isn't it?' is extremely unlikely to balance this with compassion and justice for its own pensioners and its own low-paid.

- Speech in Worsley, Lancashire (11 March 1972), quoted in The Times (13 March 1972), p. 4

- The next Labour Government can be content with nothing less than the elimination of poverty as a social problem. ... The Labour movement was created to fight against a wealthy minority on behalf of a poor majority. Now it has a more complex and demanding task. It has to enlist the majority in a struggle on behalf of a poor minority, who on grounds of age or health or family circumstances or disgracefully low pay are unable to help themselves. No one has a right to expect a fair deal for himself unless he is prepared to work for one for others too.

- Speech in Worsley, Lancashire (11 March 1972), quoted in The Times (13 March 1972), p. 4

- We have to persuade men and women who are themselves reasonably well off that they have a duty to forgo some of the advantages they would otherwise enjoy for the sake of others who are much poorer. We have to persuade car workers in my constituency that they have an obligation to low-paid workers in the public sector. We have to persuade the British people as a whole that they have an obligation to Africans and Asians whom they have never seen. Our only hope is to appeal to the latent idealism of all men and women of good will, irrespective of their income brackets, irrespective of their class origins. In place of the politics of envy, we must put the politics of compassion; in place of the politics of cupidity, the politics of justice; in place of the politics of opportunism, the politics of principle. Only so can we hope to succeed. Only so will success be worth having.

- Speech in Worsley, Lancashire (11 March 1972), quoted in The Times (13 March 1972), p. 4

- What is more likely [if there were a referendum]...is that party loyalties would be strongly mobilized and that in order to frustrate the government of the day the Opposition would form a temporary coalition of those who, whatever their political views, were against the proposed action. By this means we would have forged a more powerful continuing weapon against progressive legislation than anything we have known in this country since the curbing of the absolute powers of the old House of Lords. Apart from the obvious example of capital punishment, I would not in these circumstances fancy the chances, to take a few random but important examples, of many measures to improve race relations, or to extend public ownership, or to advance the right of individual dissent, or to introduce the planning restraints which will become increasingly necessary if our society is to avoid strangling itself.

- Letter to Harold Wilson resigning the deputy leadership of the Labour Party, quoted in The Times (11 April 1972), p. 4

- There has been a lot of talk about the formation of a new centre party. Some have even been kind enough to suggest that I might lead it. I find this idea profoundly unattractive. I do so for at least four reasons. First, I do not believe that such a grouping would have any coherent philosophical base...A party based on such a rag-bag could stand for nothing positive. It would exploit grievances and fall apart when it sought to remedy them. I believe in exactly the reverse sort of politics...Second, I believe that the most likely effect of such an ill-considered grouping would be to destroy the prospect of an effective alternative government to the Conservatives...Some genuinely want a new, powerful anti-Conservative force. They would be wise to reflect that it is much easier to will this than to bring it about. The most likely result would be chaos on the left and several decades of Conservative hegemony almost as dismal and damaging as in the twenties and thirties. Third, I do not share the desire, at the root of much such thinking, to push what may roughly be called the leftward half of the Labour Party...out of the mainstream of British politics...Fourth, and more personally, I cannot be indifferent to the political traditions in which I was brought up and in which I have lived my political life. Politics are not to me a religion, but the Labour Party is and always had been an instinctive part of my life.

- Speech to the Oxford University Labour Club (9 March 1973), quoted in The Times (10 March 1973), p. 4

- It is not much good talking about fundamental and irreversible changes in our society and being content with a 38 per cent Labour voting intention. ... Democracy means that you need a substantially stronger moral position than this to govern effectively at all, let alone effecting a peaceful social revolution. The programme we put forward must be capable of being carried out in what may well be difficult economic circumstances.

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference debate on nationalisation (2 October 1973), quoted in The Times (3 October 1973), p. 5

- [Roy Jenkins] agreed with many of the criticisms levelled against the performance of private industry and he agreed that the country needed a sharp change. There was a case for a significant extension of public ownership. (Applause.) But public ownership must be related directly to the ordinary Labour voters and the potential Labour voters in their day to day lives, particularly in development areas, to inflation, housing, and land use. "It is no good taking over a vast number of industries without a clear plan as to how and by whom they are going to be run. It is no good pretending that a transfer of ownership in itself solves our problems."

- Speech to the Labour Party Conference debate on nationalisation (2 October 1973), quoted in The Times (3 October 1973), p. 5

- The sense of shame that the Chancellor should have felt is far more personal. It is a sense of shame for having taken over an economy with a £1,000 million surplus and running it to a £2,000 million deficit. It is a sense of shame for having conducted our internal financial affairs with such profligacy that our public accounts are out of balance as never before. It is a sense of shame for having presided over the greatest depreciation of the currency, both at home and abroad, in our history. It is a sense of shame for having left us at a moment of test far weaker than most of our neighbours...There is, I believe, a greater threat to the effective working of our democratic institutions than most of us have seen in our adult lifetimes. I do not believe that it springs primarily from the machinations of subversively-minded men, although no doubt they are there and are anxious to exploit exploitable situations. It comes much more dangerously from a widespread cynicism with the processes of our political system. I believe that the Chancellor contributed to that on Monday. I believe that it poses a serious challenge to us all...None of us should seek salvation through chaos. There is a duty too to recognise that we could slip into a still worse rate of inflation and a world spiral-ling downwards towards slump, unemployment and falling standards, with our selves, temporarily at least, well in the vanguard. What is required is neither an imposed solution nor an open hand at the till. The alternative to reaching a settlement with the miners is paralysis...The task of statesmanship is to reach a settlement but to do it in a way which opens no floodgates for if they were opened, it would not only damage everyone but it would undermine the differential which the miners deserve and which the nation now needs them to have.

- Speech in the House of Commons (19 December 1973)

- ...one should not doubt that there is in Britain a great body of moderate, rather uncommitted opinion, and that unless substantial sections of such opinion can feel happy in supporting one or other of the major parties the result will be an intolerable strain upon the traditional pattern of politics. ... The stalemate will not be broken unless and until we can move over to the Labour Party a sizable part of this potentially progressive, but non-extreme opinion. I do not think that has happened yet.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- If we are to get through the immense problems of the next few years we need to heal and not to deepen the wounds of the nation. That can, I believe, be done upon the basis of party government. ... But it cannot be done upon the basis of ignoring middle opinion and telling everyone who does not agree with you to go to hell.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- ...we are a party dedicated to the rule of law and to parliamentary democracy. What the law says, even if we don't like it, is what we have to accept until we can change it by constitutional means. No one is entitled to be above the law. If we weaken on that principle we can say goodbye to democratic socialism, because what is sauce for the goose will be sauce for the gander, and there are plenty of right-wing elements who if given the excuse would gain momentum in defying future measures of social progress which they would not like. That is and will be my policy as long as I am at the Home Office.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- ...it must be clear that a future Labour Government intends to keep Britain fully part of the Western community of nations. ... Today there is a greater danger of that community falling apart than at any time since 1947. ... I myself believe that the threat of such a breakup would be greatly exacerbated by our withdrawal from Europe. ... There is no future for an isolationist Britain. If anyone wants a Britain poised uneasily between the Western alliance and the Communist block they can in the immortal words of Mr Sam Goldwyn "include me out".

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- But this is not merely a question of our political and military posture. It also affects our economic policy. We have to live and trade in an open world. We cannot make ourselves a closed society in which we can only keep men and capital by erecting a ring fence around ourselves so that they have to stay. ... To sustain it [our overseas deficit]—and the only alternative would be a drastic cut in our standard of living and a considerable contribution to the dislocation of world trade—we shall have to borrow and go on borrowing a great deal from abroad. To pretend that you could get this money in while retreating into a siege economy would be to live in a world of dangerous phantasy.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- I am in favour of sensible, well argued extensions of public ownership. ... But I am also in favour of a healthy, vigorous and profitable private sector. We do and shall depend upon it to provide a great part of our jobs, our exports and our production. And if we allow a mood of sullen uncertainty to build up in that sector we shall lose more than we shall gain by the sensible and necessary extension of the public sector.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- ...we must recognise that the greatest threat to the cohesion of our society today is the still increasing rate of inflation. ... We are approaching a new threshold...which is a rate with which hardly any democratic system in the world has so far survived. ... No country can accept this rate of inflation for more than a very short period. ... Its effects will be unfair, divisive, unsettling and in the last resort destructive. ... No one will be able to plan ahead. The country will not for long put up with it. If we cannot solve it by tolerable and civilized methods, then someone within a few years will solve it by intolerable and uncivilized ones.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- We must restore some stability and be prepared, if necessary, to make some sacrifices, both of dogma and materialism, to achieve it. There is no point in pretending that we are not facing an economic crisis without precedent since the growth of post-war prosperity.

- Speech to the Pembrokeshire Constituency Labour Party in Haverfordwest (26 July 1974), quoted in The Times (27 July 1974), p. 3

- What makes you think I care about my political career? All that matters to me is what is happening in the world, which I think is heading for disaster. I can't stand by and see us pretend everything is all right when I know we are heading for catastrophe. It isn't only Europe. It is a question of whether this country is going to cut itself off from the Western Alliance and go isolationist.

- Remarks to Barbara Castle (30 July 1974), quoted in Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries, 1974–76 (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), pp. 159–160

- [I] could not stay in a Cabinet which had to carry out withdrawal [from the EEC].

- Remark (26 September 1974), quoted in The Times (27 September 1974), p. 1

- It is the police who are our main protection against terrorism and it is to the police that we must give our sustenance and support. It cannot be without reluctance that we contemplate powers of the kind proposed in the Bill, involving as they must some encroachment—limited but real—on the liberties of individual citizens. Few things would provide a more gratifying victory to the terrorists than for this country to undermine its traditional freedoms in the very process of countering the enemies of those freedoms. This we must keep in mind not only today but in the future as we persevere in what may not be a short struggle to eradicate terrorism from this country...the Bill proposes strengthened powers in four broad areas. First, it proscribes the IRA and makes display of support for it illegal. Second, the Bill makes it possible to make exclusion orders against persons who are involved in terrorism. Third, the Bill gives the police wide powers to arrest and detain, within limits, suspected terrorists. Fourth, it gives the police powers to carry out a security check on all travellers entering and leaving Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

- Speech in the House of Commons introducing the Prevention of Terrorism Act (28 November 1974)

- Inflation in Britain is at an unacceptable level. It is now mostly home-induced and wage-induced. It is moving well out of line with that of the rest of the world. If it goes on doing so it will ruin us as a nation, both economically and politically. It is of a different order from any of our other difficulties. It is, quite simply, our biggest menace since Hitler.

- Hugh Anderson Memorial lecture at the Cambridge Union (28 February 1975), quoted in The Times (1 March 1975), p. 2

- Let there be no doubt that our present rate of inflation is the main cause of our economic difficulties. There never has been a more mistaken piece of economic analysis than the view that we should accept inflation to avoid unemployment. Inflation today, so far from being an alternative to unemployment, is its main cause. If our rate of cost increase is allowed to continue close to twice that of the average for the developed world it will increasingly price us out of world markets. Employers...will have to restrict their activities and still more their labour force in response to mounting and uncontainable wage and salary bills.

- Hugh Anderson Memorial lecture at the Cambridge Union (28 February 1975), quoted in The Times (1 March 1975), p. 2

- Not to have gone into Europe would, in my view, have been a misfortune. But to come out would be on an altogether greater scale of self-inflicted injury. It would be a catastrophe. ... I care very much about the influence of Britain in the world, and also about our capacity to control our own destiny. To me, that is much more important than the legalistic definition of sovereignty.

- Speech at the St Ermin's Hotel, Westminster (26 March 1975), quoted in The Times (27 March 1975), p. 8

- Were we to leave [the EEC], the worst damage would be done to ourselves. But not only damage. Western unity, at a time of great international danger, is under greater strain than at any time since it was put together in the aftermath of the war a generation ago. Were we to start to disengage, the whole delicate but precious structure might begin to fall apart.

- Speech at the St Ermin's Hotel, Westminster (26 March 1975), quoted in The Times (27 March 1975), p. 8

- The myths about the evils of the [European] Community grow ever more manifold as day passes day. We are told that it would prevent any advance of public ownership. What happened to British Leyland during the past two days? The truth is almost the reverse. It is not the change of ownership which is threatened by staying in, it is the basic plan for buttressing and rejuvenating British Leyland and saving the jobs which go with it which would be fatally undermined by coming out.

- Speech to the Labour Party conference on Britain's membership of the EEC (26 April 1975), quoted in The Times (28 April 1975), p. 4

- He could not regard the question of sovereignty as the ark of the covenant of socialism. It was neither socialist nor realistic to think one could have sovereignty in the world of today. "We live in an integrated world and our duty is to play our part in that with our neighbours. I distrust people who proclaim their love for humanity but illustrate it by being unable to get on with those around them."

- Speech to the Labour Party conference on Britain's membership of the EEC (26 April 1975), quoted in The Times (28 April 1975), p. 4

- I find it increasingly difficult to take Mr Benn seriously as an economics minister.

- Britain in Europe press conference (27 May 1975), quoted in The Times (28 May 1975), p. 3

- [Britain outside the EEC would go into] an old people's home for fading nations. I do not believe in premature senility, either for nations or for individuals. And I do not even think it would be a comfortable or agreeable old people's home. I do not much like the look of some of the prospective wardens. I do not think the food or heating supplies would be very secure. There would be nobody much to pay for renovations. Our old friends would not much want to come and see us (the axis of power would run increasingly from Washington to Bonn or Brussels). We would find it increasingly difficult to afford to go and see them; and even if we got there we might find ourselves greeted on the doorstep with more embarrassment than welcome.

- Britain in Europe press conference (27 May 1975), quoted in The Times (28 May 1975), p. 3

- If Reg Prentice is cut down it is not just the local party that is undermining its own foundations by ignoring the beliefs and feelings of ordinary people, the whole legitimate Labour Party, left as well as right, is crippled if extremists have their way. ... If tolerance is shattered formidable consequences will follow. Labour MPs will either have to become creatures of cowardice, concealing their views, trimming their sails, accepting orders, stilling their consciences, or they will all have to be men far far to the left of those whose votes they seek. Either would make a mockery of parliamentary democracy. The first would reduce still further, and rightly reduce, respect for the House of Commons. It would become an assembly of men with craven spirits and crooked tongues. The second would, quite simply, divorce the Labour Party from the people.

- Speech in Newham, London (11 September 1975), quoted in The Times (12 September 1975), p. 1

- I do not think you can push public expenditure significantly above 60 per cent [of GNP] and maintain the values of a plural society with adequate freedom of choice. We are here close to one of the frontiers of social democracy.

- Speech in Anglesey (23 January 1976), quoted in The Times (24 January 1976), p. 2

- ...be prepared first to look at the evidence and to recognize how little the widespread use of prison reduces our crime or deals effectively with many of the individuals concerned. [The rule of law does not mean] our own pet prejudices. It means, in a democratic society, the law as passed by an elected Parliament and applied by impartial courts. You cannot have a rule of law while dismissing with disparagement Parliament, the courts and those who practise in them. That is not the rule of law. It is exactly what the pressure groups you complain about seek to achieve by demonstration.

- Speech to the Police Federation conference in Eastbourne (18 May 1976), quoted in The Times (19 May 1976), p. 5

- I respect your right to put them to me. You will no doubt respect my right to tell you that I do not think all the points in sum amount to a basis for a rational penal policy.

- Speech to the Police Federation conference in Eastbourne (18 May 1976) regarding the Federation's campaign on law and order, quoted in The Times (19 May 1976), p. 5

- Our determination to ensure good community relations is unswerving. There is no room for racial hatred in our crowded island. We cannot afford not to make a success of a multi-racial society. A moving speech was made the other day in the other place by Lord Pitt, himself a distinguished citizen of London of West Indian origin. In that speech, he looked forward hopefully to a harmonious multiracial Britain setting an example to the world. He spoke on a high level of moral seriousness, but reminded us too that our self-interest is also served by racial harmony and tolerance. I agree with that view, and would share Lord Pitt's hope, but I do not see it as an easy or even a certain outcome, at any rate in this generation. Its accomplishment will depend on the minority community accepting that this country will not take, in Lord Pitt's own words, a "large and unending stream" of dependants, and on the majority community accepting that tolerance is one of the greatest and most traditional of British virtues and that if that tradition is broken we shall all of us suffer deeply, both minority and majority, and suffer for many years to come.

- Speech in the House of Commons (5 July 1976)

- My wish is to build an effective united Europe. Now I've never sought absolutely to define exactly what I mean by this, but I've got an absolute clear sense of direction. I've never been frightened about the pace being too fast, I have been frightened about the pace being too slow. I do not think it's terribly useful to lay down blueprints as to whether one will be federal or confederal in the year 2000 and beyond. I want to move towards a more effectively organized Europe politically and economically and as far as I am concerned I want to go faster, not slower.

- Interview with The Times (5 January 1977), p. 8

- I think that British politics, as at present constituted do make it difficult for people who are essentially men of the centre—I am a man of the left centre, but I've never pretended to be terribly far away from the centre of British politics. ... The gladiatorial nature of the House of Commons, with two sides lined up against each other, puts a premium on disagreement rather than upon agreement. This is inclined on both sides to give a greater strength to the wings rather than to the centre. ... there are appalling economic problems facing this country at the present time...I don't think it's terribly useful, terribly relevant or terribly convincing just to engage in an endless game of tu quoque. You've got to think of something better than 'It's your fault',—'No, it's not, it's your fault'. There's a sterility in this which is a danger to the country.

- Interview with The Times (5 January 1977), p. 8

- There has always been a left, an extreme left, in the Labour Party. ... there is now more of an attempt, patchy, but an attempt by extremist organizations to infiltrate and work through the Labour Party at the present time—the phrase is 'entryism'. It is something which is certainly there and which one certainly has to beware of.

- Interview with The Times (5 January 1977), p. 8

- If one looks at the evolution of Europe, you can say we've got a customs union, we've got the common agricultural policy, we've got certain other forms of integration and cohesion, but many of the hopes of the founding fathers are still very far from being realized.

- Interview with The Times (5 January 1977), p. 8

- Those who had most insistently demanded the innovation of the referendum, because they thought it would produce exactly the opposite result, were temporarily stunned by the sudden revelation that they were populists without the support of the people. Now they have recovered from their concussion and seek to reopen the issue. ... Even if they had a coherent alternative policy, which they do not, it would wreck itself upon the rock of inconstancy. ... No one any longer expects us to be a rich country. But with an almost touching faith they still hope that we will be consistent and reliable. It is exactly this store of remaining national credit which the false democrats who first demanded and now deny the referendum seek to undermine.

- Speech in Glasgow (1 July 1977), quoted in The Times (2 July 1977), p. 1

- We must relaunch with a newly defined relevance to the circumstances of the late 1970s the drive towards economic and monetary union. We must find ways of avoiding recourse to the danger of psuedo-solutions of national protectionism to threats to sensitive sectors of the economy.

- Speech in Brussels (7 October 1977), quoted in The Times (8 October 1977), p. 4

- [The effect of the Suez Crisis on the French was quite different.] We turned across the Atlantic. They turned across the Rhine, and Europe was built without us. There is room for argument about the causes of what followed. There is no doubt about what happened. Over the first 13 years of the [European] Community's life national income per head increased by 72 per cent in the Six and by 35 per cent in Britain. The result was that from being almost the richest country in Western Europe we became one of the poorest. France for the first time since the industrial revolution surpassed us in economic strength. The German economy achieved nearly twice our weight.

- The Richard Dimbleby Lecture ('Home Thoughts from Abroad') (22 November 1979), quoted in The Times (23 November 1979), p. 5

- Do we really believe that we have been more effectively and coherently governed over the past two decades than have the Germans, with their very sensible system of proportional representation? The avoidance of incompatible coalitions? Do we really believe that the last Labour Government was not a coalition, in fact if not in name, and a pretty incompatible one at that? I served in it for half its life, and you could not convince me of anything else.

- The Richard Dimbleby Lecture ('Home Thoughts from Abroad') (22 November 1979), quoted in The Times (23 November 1979), p. 5

- You also make sure that the state knows its place, not only in relation to the economy, but in relation to the citizen. You are in favour of the right of dissent and the liberty of private conduct. You are against unnecessary centralization and bureaucracy. You want to devolve decision-making wherever you sensibly can. You want parents in the school system, patients in the health service, residents in the neighbourhood, customers in both nationalized and private industry, to have as much say as possible. You want the nation to be self-confident and outward-looking, rather than insular, xenophobic and suspicious. You want the class system to fade without being replaced either by an aggressive and intolerant proletarianism or by the dominance of the brash and selfish values of a 'get rich quick' society. ... These are some of the objectives which I believe could be assisted by a strengthening of the radical centre.

- The Richard Dimbleby Lecture ('Home Thoughts from Abroad') (22 November 1979), quoted in The Times (23 November 1979), p. 5

- During this conversation she vouchsafed her only awareness of Dimbleby. The Belgian Prime Minister was justifying his hesitancy about cruise missiles by citing his coalition difficulties. Mrs Thatcher turned to me with a mixture of belligerence, good humour and total self-satisfaction and announced to a slightly bewildered table – none of them elected by the British system – "And that is all your great schemes would amount to."

- Diary entry recording the Council of Ministers meeting in Dublin (29 November 1979), quoted in Roy Jenkins, European Diary, 1977–1981 (1989), p. 529

1980s

[edit]- [A]lmost without a struggle, we have just witnessed a major lurch to the left in policy-making. The supreme authority of the Labour Party committed itself nine days ago to...a near neutralist and unilateralist position, which would make meaningless our continued membership of NATO...a commitment to practical non-cooperation with the European Community, leading in all likelihood to a firm proposal for complete withdrawal...a massive further extension of the public sector, despite the manifold unsolved problems which beset our nationalised industries, and mounting evidence from all over the world that full-scale state ownership is more successful in producing tyranny than in producing goods. Capitalism has its crisis today, but so too does estate socialism. There is now no economic philosopher's stone. But more successful nations are those which embrace a mixed economy and follow it with some consistency of purpose, not forever changing the frontiers. What remains of the private sector is to have enterprise squeezed out of it by being subjected to a straightjacket far tighter than in any other democratic country in the world.

This is not by any stretch of the imagination a social democratic programme. Nor do I believe that it is the way to protect Britain's security, help the peace of the world, revitalise our economy, or represent the views of the great majority of moderate left voters.- Speech to the Parliamentary Press Gallery (9 June 1980), quoted in The Times (10 June 1980), p. 2

- I therefore believe that the politics of the left and centre of this country are frozen in an out-of-date mould which is bad for the political and economic health of Britain and increasingly inhibiting for those who live within the mould. Can it be broken? ... There was once a book, more famous for its title than for its contents, called the Strange Death of Liberal England. That death caught people rather unawares. Do not discount the possibility that in a few years time someone may be able to write at least equally convincingly of the strange and rapid revival of liberal social democratic Britain.

- Speech to the Parliamentary Press Gallery (9 June 1980), quoted in The Times (10 June 1980), p. 2

- The two main parties feared the SDP more than they feared each other. Their narrow dogmas had alienated more and more people and would never achieve a widening appeal across classes, regions and occupations. They had replied by trying to pretend that the SDP was all things to all men and women. It was not true. ... It had no place for class warriors or for those who wanted to fight outdated ideological battles; no place for little Englanders; for those selfishly concerned with their own problems and not with those of their neighbours and the nation as a whole. The Labour Party went increasingly into its chauvinist bunker and the Conservative Party showed little or no concern for the problems of the developing and poor nations.

- Speech in Kensington (14 February 1982), quoted in The Times (15 February 1982), p. 4

- Many of the early nationalisation measures were right. They have remained part of the social fabric. I favour measures of that type.

- Speech in the House of Commons (Hansard, 10th November 1982, Col. 579).

- The whole spirit and outlook of the [SDP] party, its leaders and its members must be profoundly opposed to Thatcherism. It could not go along with the fatalism of the Government's acceptance of massive unemployment.

- First Tawney Lecture (11 July 1984), quoted in The Times (13 July 1984), p. 2

- A rolling back of the frontiers of State surveillance is necessary. ... I have come to the conclusion that this side of MI5 has become more trouble than it is worth. It falls over its own feet too often. It arouses more suspicion and complaint than is justified by the results its achieves. ... On grounds of utility I would now close down the political side of its activities.

- Letter to The Times (12 March 1985), p. 15

- First, there is really no sign at all of any significant reduction in unemployment without a major change in policy...Unemployment has probably levelled out but at a totally unacceptable figure. Secondly, contrary to what the Secretary of State said, the post-oil surplus prospect—not merely the post-oil prospect, because the oil will take a long time to go, but the surplus, the big balance of payments surplus, which is beginning to decline quite quickly—still looks devastating...our balance of payments is now overwhelmingly dependent on this highly temporary and massive oil surplus. Our manufacturing industry is shrunken and what remains is uncompetitive...We have a manufacturing trade deficit of approximately £11 billion, all of which has built up in the past three to four years. This is containable by oil and by nothing else. Invisibles can take care of about £4 billion or £5 billion but they cannot do the whole job. As soon as oil goes into a neutral position we are in deep trouble. Should it go into a negative position, the situation would be catastrophic...To sell off a chunk of capital assets and to use the proceeds for capital investment in the rest of the public sector might just be acceptable. However, that is not what is proposed, and what is proposed cannot be justified on any reputable theory of public finance; and when it is accompanied by a Minister using the oil—which might itself be regarded as a capital asset; certainly it is not renewable—almost entirely for current purposes, it amounts to improvident finance on a scale that makes the Prime Minister's old friend General Galtieri almost Gladstonian.

- Speech in the House of Commons (12 November 1985).

- Several fallacies have been accepted too freely recently about the position of our manufacturing industry in the balance of our economy. The biggest fallacy is the view that salvation lies in services, and only in services. The corollary to that is that it is inevitable and desirable that over the past two decades there has been a reduction of nearly 3 million in employment in manufacturing industry. That is a massive reduction and represents nearly 40 per cent. of the total in manufacturing industry over that time. I do not believe that that should have been the case. That has been precipitate and dangerous and it has not been associated with an increase in productivity which has led to our maintaining our relative manufacturing position...I have come increasingly to the view that the Government stand back too much from industry. In my experience, they do so more than any other Government in the European Community. They do so more than the United States Government. We have to remember the vast US defence involvement in industry. They certainly stand back more than do the Japanese Government. To some extent, the motive is the feeling that we have had an uncompetitive and rather complacent industry which must be exposed to the full blasts of competition, and if that means contracts, even Government contracts, going overseas, we should shrug our shoulders and say that the wind should be stimulating. That process has been carried much further in Britain than in any other comparable rival country. I am resolutely opposed to protectionism. I am sure that it diminishes the employment and wealth-creating capacity of the world as a whole. That would be the result of plunging back into that policy. I also believe, however, that this totally arm's-length approach in the relationship between Government and industry is something that no other comparable Government contemplate to the extent that we do. It is not producing good results for British industry and it is a recipe for a further decline in Britain's position in the Western world. The Government should examine it carefully and reverse it in several important respects.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 July 1986)

- The combined efforts of Government policy since 1979 have been not to improve but substantially to worsen our competitive position. We have gone from a huge manufacturing surplus of £5.5 billion in 1980 to a 1986 third quarter deficit of £8 billion a year...Even with oil production continuing for some time, the current account has gone from a £3 billion surplus to a deficit predicted by the Chancellor of £1.5 billion...Sadly, the Government's great contribution, having refused to stimulate the economy by more respectable means, is a roaring consumer boom, which there is not the slightest chance of their moderating before an election. A roaring consumer boom does not, to any significant extent, mean more employment. In our competitive position, worsening under the Government, it means overwhelmingly higher imports, a still worse balance of payments position and a classic path to perdition. To have produced, after seven and a half years, the combination of total monetary muddle, a worsened competitive position, a widespread doubt in other countries as to how we are to pay our way in the future, a desperately vulnerable currency and the prospect of an unending plateau of the highest unemployment in a major country in the industrialised world is a unique achievement over which the Chancellor is an appropriate deputy acting presiding officer.

- Speech in the House of Commons (6 November 1986)

- We have Mr. Wright's allegation that a surveillance operation was mounted against Lord Wilson of Rievaulx when he was Prime Minister in the mid-1970s...Many criticisms can be made of Lord Wilson's stewardship—I have made some in the past and I have no doubt that I may make some more in future—but the view that he, with his too persistent record of maintaining Britain's imperial commitments across the world, with his over-loyal lieutenancy to Lyndon Johnson, with his fervent royalism, and with his light ideological luggage, was a likely candidate to be a Russian or Communist agent is one that can be entertained only by someone with a mind diseased by partisanship or unhinged by living for too long in an Alice-Through-the-Looking-glass world in which falsehood becomes truth, fact becomes fiction and fantasy becomes reality. The result of the allegation has been substantially to fortify the view that I expressed in a letter to The Times 18 months ago, which is that MI5 should now be pulled totally out of its political surveillance role.

- Speech in the House of Commons (3 December 1986)

- It is the duty of the state to lean firmly but unvindictively in favour of greater equality.

- Speech in the House of Commons (18 March 1987)

- They [the Government] argue that if the rich are made rich enough, some wealth will spill over to make the poor less poor. There is no sign of that happening. On the contrary, the gap has widened. The number of those below the poverty line and with little hope of rising above it has grown inexorably. Connected divides become deeper and wider—that between the employed and the unemployed, that between the north and south, and that between those who share prosperity and those to whom it looks like a closed fortress. The Budget...does nothing to counteract that. ... If I were the Chancellor, I would be deeply apprehensive for the future cohesion of our society under his policies.

- Speech in the House of Commons (18 March 1987)

- I therefore think that our negotiations have achieved a satisfactory prospectus for an electable left-of-centre alternative to Thatcherism. And that was what the SDP was always intended to be: a party which was free alike of proletarian sullenness or of bourgeois triumphalism and which challenged both the old arrogance that the establishment always knows best (particularly if it can use secrecy to prevent anyone judging whether it really does) and the new heresy that the mystical entity of "the market" can run everything. A controlled economy is not much good at producing consumer goods. But "the market", in terms of protecting the environment or safeguarding health, schools, universities or Britain's scientific future, cannot run a whelk-stall. And if asked which is under greater threat in Britain today, the supply of consumer goods or the nexus of civilized public services, I unhesitatingly answer the latter.

- 'Why the middle must hold', The Times (30 January 1988), p. 8

- Undoubtedly, looking back, we nearly all allowed ourselves, for decades, to be frozen into rates of personal taxation which were ludicrously high...That frozen framework has been decisively cracked, not only by the prescripts of Chancellors but in the expectations of the people. It is one of the things for which the Government deserve credit...However, even beneficial revolutions have a strong tendency to breed their own excesses. There is now a real danger of the conventional wisdom about taxation, public expenditure and the duty of the state in relation to the distribution of rewards, swinging much too far in the opposite direction...I put in a strong reservation against the view, gaining ground a little dangerously I think, that the supreme duty of statesmanship is to reduce taxation.

- Speech in the House of Lords (24 February 1988)

- We have been building up, not dissipating, overseas assets. The question is whether, while so doing, we have been neglecting our investment at home and particularly that in the public services. There is no doubt, in my mind at any rate, about the ability of a low taxation market-oriented economy to produce consumer goods, even if an awful lot of them are imported, far better than any planned economy that ever was or probably ever can be invented. However, I am not convinced that such a society and economy, particularly if it is not infused with the civic optimism which was in many ways the true epitome of Victorian values, is equally good at protecting the environment or safeguarding health, schools, universities or Britain's scientific future. And if we are asked which is under greater threat in Britain today—the supply of consumer goods or the nexus of civilised public services—it would be difficult not to answer that it was the latter.

- Speech in the House of Lords (24 February 1988)

- In retrospect we might have been more cautious about allowing the creation in the 1950s of substantial Muslim communities here, although when one observes the, in some ways, greater problems which France and Germany have in this respect, it is an illusion to believe that in the integrated world of today any major country can remain exclusively indigenous.

- 'On Race Relations and the Rushdie Affair', The Independent Magazine (4 March 1989), p. 16, quoted in Elham Manea, Women and Shari'a Law: The Impact of Legal Pluralism in the UK (I.B. Tauris, 2016), p. 256.

1990s

[edit]- My broad position remains firmly libertarian, sceptical of official cover-ups and uncompromisingly internationalist, believing sovereignty to be an almost total illusion in the modern world, although both expecting and welcoming the continuance of strong differences in national traditions and behaviour. I distrust the deification of the enterprise culture. I think there are more limitations to the wisdom of the market than were dreamt of in Mrs Thatcher's philosophy. I believe that levels of taxation on the prosperous, having been too high for many years (including my own period at the Treasury), are now too low for the provision of decent public services. And I think the privatisation of near monopolies is about as irrelevant as (and sometimes worse than) were the Labour Party's proposals for further nationalisation in the 1970s and early 1980s.

- A Life at the Centre (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 617

- ...my natural prejudices, such as they are, are much more green than orange. I am a poor unionist, believing intuitively that even Paisley and Haughey are better at dealing with each other than the English are with either.

- Portraits and Miniatures: Selected Writings (London: Macmillan, 1993), pp. 310–311.

- ...the basic fact of Tony Blair's election does make it, in my view, the most exciting Labour choice since the election of Hugh Gaitskell in December 1955. ... The most fundamental presentation issue for the Labour Party is one of openness or inwardness. Nothing does the party more harm than when it turns in on itself in a mood of proletarian sullenness. Tony Blair epitomises the reverse of this. ... I hope he will use this opportunity in favour of sticking to a constructive line on Europe, in favour of sensible constitutional innovation...and in favour of friendly relations with the Liberal Democrats. ... I hope Mr Blair will not lead the Labour Party further in a free-market direction. Good work has been done in freeing it from nationalisation and other policies. But the market cannot solve everything and it would be a pity to embrace the stale dogmas of Thatcherism just when their limitations are becoming obvious.

- 'Labour's most exciting leader since Gaitskell', The Times (23 July 1994), p. 14

- I have three great interests left in politics, a single currency, electoral reform, and the union of the Liberals with Labour. And all three are languishing.

- Remark to Robert Harris (November 1999), quoted in Robert Harris, 'A Late Friendship', in Andrew Adonis and Keith Thomas (eds.), Roy Jenkins: A Retrospective (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 311

2000s

[edit]- My central belief is that there are only two coherent British attitudes to Europe. One is to participate fully in all the main activities of the Union and to endeavour to exercise as much influence and gain as much benefit as possible from inside. The other is to recognise that Britain's history, national psychology and political culture may be such that we can never be other than a foot-dragging and constantly complaining member. If so, it would be better, and certainly would produce less friction, to accept this and to move towards an orderly and, if possible, reasonably amicable withdrawal.

- 'Britain and Europe: The problem with being half pregnant', in Keith Sutherland (ed.), The Rape of the Constitution? (Imprint Academic, 2000), p. 277

- My view is that the Prime Minister [Tony Blair], far from lacking conviction, has almost too much, particularly when dealing with the world beyond Britain. He is a little too Manichaean for my perhaps now jaded taste, seeing matters in stark terms of good and evil, black and white, contending with each other, and with a consequent belief that if evil is cast down good will inevitably follow. I am more inclined to see the world and the regimes within it in varying shades of grey. The experience of the past year, not least in Afghanistan, has given more support to that view than to the more Utopian one that a quick "change of regime" can make us all live happily ever after.

- Speech in the House of Lords (24 September 2002) shortly before the Iraq War

- I am in favour of courage—who is ever not in the abstract?—but not of treating it as a substitute for wisdom, as I fear we are currently in danger of doing.

- Speech in the House of Lords (24 September 2002) shortly before the Iraq War

Quotes about Jenkins

[edit]1960s

[edit]- He is a superb debater, skilful in his deployment of argument, sensitive to the mood of the House, sometimes commanding in his use of language. However harshly his Budgets may hit the pocket, at least they should fall pleasantly on the ear... [H]e has today a more committed personal following than any other senior Labour politician... [T]he impression being built up of him as an intelligent, liberal, idealistic figure has won him some support even on the left, in addition to his firm adherents among the younger men of the centre and right.

- Ian Trethowan, 'Mr Jenkins blooded well for the task', The Times (30 November 1967), p. 11

- As a parliamentary performer...Mr Jenkins is a class apart from the rest of either front bench... He not only looks superior: he is superior.

- Alan Watkins, New Statesman (1 December 1967), quoted in John Campbell, Roy Jenkins: A Well-Rounded Life (2014), p. 305

- Roy Jenkins has risen fully and magnificently to the occasion. Yesterday's Budget was really everything that was economically needed. It should give devaluation a virtually certain guarantee of success.

- Peter Jay, 'Jenkins to the rescue', The Times (20 March 1968), p. 25

1970s

[edit]- He may not be a Socialist but at least he is a radical. Jim is neither.

- Barbara Castle, diary entry (7 June 1971), quoted in John Campbell, Roy Jenkins: A Well-Rounded Life (2014), p. 370

- Roy's drawl always lengthens when he is angry, which heightens the effect of contempt.

- Barbara Castle, diary entry (5 April 1974), quoted in Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries, 1974–76 (1980), p. 72

- The trouble with Roy is that he is so damned civilized. If only he could remain civilized and have an injection of red blood as well.

- Barbara Castle, diary entry (16 September 1974), quoted in Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries, 1974–76 (1980), p. 182

- Rousseau's educational theories had persuaded teachers] to dispense with the structured systems of learning which have been so successful in the past. [The result is] the belief, taught by Mr Roy Jenkins, that a permissive is a civilised society... A facile rhetoric of total liberty and of costless, superficial universal protest has really been a cover for irresponsibility. Our loud talk about the community overlies the fact that we have no community. We talk about neighbourhoods and all too often we have no neighbours. We go on about the home when we only have dwelling places containing television sets. It is the absence of a frame of rules and community, place and belonging, responsibility and neighbourliness that makes it possible for people to be more lonely than in any previous stage in our history. Vast factories, huge schools, sprawling estates, sky-scraping apartment blocks; all these work against our community and our common involvement one with another.

- Keith Joseph, Speech in Luton (3 October 1974), quoted in Andrew Denham and Mark Garnett, Keith Joseph (2001; 2002), p. 262

1980s

[edit]- The "Council of Social Democracy" seems an awfully dull name. I was going to suggest that the Jenkins–Williams group should be called the League of Agweeable Fellows Incommoded by Tiresome Extweemism – or Lafite for short... Mr Jenkins himself is possibly the most over-rated figure in British politics, a competent administrator but an uninspiring speaker and an irritating writer. He gave his political testament in the Dimbleby Lecture the November before last: "You want the class system to fade without being replaced either by an aggressive and intolerant proletarianism or by the dominance of the brash and selfish values of a 'get rich quick' society." In other words, as Ferdinand Mount glossed at the time, you want to keep the yobs away from the best claret.

- Geoffrey Wheatcroft, 'Notebook', The Spectator (31 January 1981), p. 5

- A socialite rather than a Socialist.

- Harold Wilson, press conference during the Warrington by-election (15 July 1981), quoted in The Times (16 July 1981), p. 28

- I wholly agree that Mr. Jenkins' saying that a permissive society is a civilised society is something that most of us would totally reject. Society must have rules if it is to continue to be civilised. Those rules must be observed and upheld by Government and by all leaders throughout the community.

- Margaret Thatcher, Prime Ministers' Questions in the House of Commons after the 1981 riots (16 July 1981)

- [T]his much-loved, gracious figure who is to the liberal classes what the Queen Mother is to the rest of us.

- Frank Johnson, 'The disappearing Roy – and one left earring', The Times (23 March 1982), p. 22

- [B]efore the Argentine action he was the subject of all our attention. He had won Hillhead. He had taken his seat. He has put a notably incomprehensible, but no doubt distinguished, maiden question to the Prime Minister about micro-chips. All things seemed possible for him. But within days Dr David Owen had seized the SDP controls and was roaring away on the subject of submarines, frigates, and vertical take-off. Dr Owen is at home with such matters. Mr Jenkins is not. Like Switzerland, he is prosperous, comfortable, civilized and almost entirely landlocked. His only previous contact with the high seas has been in various good fish restaurants.

- Frank Johnson, 'Jenkins rolls a jowl at the Falklands', The Times (21 April 1982), p. 26

- I went to the BBC for Question Time... Roy Jenkins was going on about Militant being a "cancer in the Labour Party", so when it came to me I turned on him and the SDP. "You talk about cancer! Everything you have achieved in your life has been on the backs of the working class. Your father was a miner; he was imprisoned in 1926; and every office you have ever held was because of the Labour Party, and then you kick away the ladder." I thought he was going to have a stroke. His face went absolutely scarlet. He is used to being buttered up as a man of principle.

- Tony Benn, diary entry (27 February 1986), quoted in Tony Benn, The End of An Era: Diaries, 1980–90, ed. Ruth Winstone (1992), p. 439

- He was not a good Chancellor. He was really responsible for the inflation which began in 1970 and continued in the years after and it was his fault.

- Nigel Lawson, remarks to Woodrow Wyatt (9 December 1986), quoted in Woodrow Wyatt, The Journals of Woodrow Wyatt, Volume One, ed. Sarah Curtis (1998), p. 242

- I thought it was horrifying that they threw him out at Hillhead. A man of such great distinction and stature. It was dreadful. It tells you something about the Scots.

- Margaret Thatcher, remarks to Woodrow Wyatt after Jenkins had lost his Glasgow Hillhead seat in the general election (14 June 1987), quoted in Woodrow Wyatt, The Journals of Woodrow Wyatt. Volume One, ed. Sarah Curtis (1999), p. 370

- In Bruce Anderson's Sunday Telegraph...article he writes about the idea that Roy Jenkins might have become Chancellor of the Exchequer in her (Mrs Thatcher's) first government... We had discussed it quite frequently and she was very interested in it, having some doubts about Geoffrey Howe at the time and recognizing how good Roy Jenkins had been at cutting expenditure.

- Woodrow Wyatt's diary (9 April 1989), quoted in Woodrow Wyatt, The Journals of Woodrow Wyatt, Volume Two, ed. Sarah Curtis (1999), p. 64

- In my view, Roy's best period in office was as Home Secretary in the Cabinet of 1966; he then succeeded in stamping his liberal humanism on a department not notorious for that quality. He was not well suited to the politics of class and ideology which played so large a role in the Labour Party. His natural environment was the Edwardian age on which he wrote so well... His appearance had the sleek pomposity of Mr Podsnap; behind it there was a sharp and unsentimental mind... Above all, he was never satisfied with second place in any field; he always wanted to be top. I believe this explains much in his career after his poor showing in the election for Labour Party leadership in 1976.

- Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (1989; 1990), p. 329

1990s

[edit]- Callaghan resigned as Chancellor after devaluation. His place was taken by Roy Jenkins who was, in my judgment, the ablest of the four Chancellors I served. He listened to advice, but made up his own mind, explaining to his advisers the grounds for his decision. He was at times able to foresee contingencies of which his staff had not warned him, such as the possible devaluation of the French franc, and was judicious in assessing such contingencies and deciding what measures were appropriate to the circumstances. He was not afraid to take extreme measures to overcome major dangers, adding more to taxation and cutting more from public expenditure than his advisers suggested and showing a sound judgment of what was at stake. This resoluteness in the circumstances in which he took office enabled him to carry the Cabinet with him after three years in which they had shrunk from much milder action.

- Alec Cairncross, Living with the Century (1998), p. 251

2000s

[edit]- A. J. P. Taylor told me in 1970, in one of those impromptu addresses to individuals that made the Beaverbrook Library so entertaining a place, that Wilson was transparently Lloyd George redivivus and Roy Jenkins an aspirant Asquith.

- Michael Bentley, Lord Salisbury's World: Conservative Environments in Late-Victorian Britain (2001), p. 317, n. 52

- [H]e is the second most successful British politician of modern times. The first is Margaret Thatcher... Roy Jenkins is one of those characters, best portrayed by Trollope, who is thoroughly worldly and yet has integrity. Power and glamour and party (and parties) all matter to him, but they matter only in a context that is, though he would avoid the phrase, morally serious. Despite his accent and demeanour (only his pronunciation of the word "sitooation" discloses the Welsh background), Jenkins has deep roots in the Labour movement. His opponents say that he severed them for snobbish reasons, but it is more likely that he did so because of a principled preference for the liberal over the tribal.

- Charles Moore, 'It's not Mandy, it's not even Tony – it's Woy wot won it', The Daily Telegraph (26 January 2001)

- And in persona, though clearly self-regarding and de haut en bas, he is also amused, self-critical, unbitter and detached. He is one of the few retired senior politicians who do not seem warped or broken by the career they have chosen. Perhaps this is because Jenkins knows that he has striven for what he believed in most of the time, and achieved a good deal of it. We are a "liberal" society in the sense in which he meant it. We are in the European Union. We have a Labour government in which the power of the labour movement has been weakened beyond Roy's wildest hopes. It's thanks to him more than any other single person. True, the whole thing is pretty ghastly, and far from the "civilised" polity he wanted. But that is not because of any personal failing: it is simply because he is, by and large, in the wrong.

- Charles Moore, 'It's not Mandy, it's not even Tony – it's Woy wot won it', The Daily Telegraph (26 January 2001)

- One of the outstanding statesmen of his era.

- James Callaghan, quoted in 'Political tributes to Roy Jenkins', BBC News (5 January 2003)

- As a founder of the SDP he was probably the grandfather of New Labour.

- Tony Benn, quoted in The Times (6 January 2003), p. 4

- One of the most remarkable people ever to grace British politics. He was a friend and support to me.

- Tony Blair, quoted in The Times (6 January 2003), p. 4

- An outstanding British statesman and a great European. He will be remembered with great esteem for his historic role in the birth of the euro.

- Romano Prodi, President of the European Commission, quoted in The Times (6 January 2003), p. 4

- Roy Jenkins was both radical and contemporary; and this made him the most influential exponent of the progressive creed in politics in postwar Britain. Moreover, the political creed for which he stood belongs as much to the future as to the past. For Jenkins was the prime mover in the creation of a form of social democracy which, being internationalist, is peculiarly suited to the age of globalisation and, being liberal, will prove to have more staying power than the statism of Lionel Jospin or the corporatist socialism of Gerhard Schröder.

- Vernon Bogdanor, 'The great radical reformer', The Guardian (12 January 2003)

- Roy Jenkins was the first leading politician to appreciate that a liberalised social democracy must be based on two tenets: what Peter Mandelson called an aspirational society (individuals must be allowed to regulate their personal lives without interference from the state); and that a post-imperial country like Britain could only be influential in the world as part of a wider grouping (the EU).

- Vernon Bogdanor, 'The great radical reformer', The Guardian (12 January 2003)

- He [James Callaghan] also rightly sensed that though the years of Roy Jenkins at the Home Office had been stellar in their action on discrimination – and he was fully supportive of that – liberalism was not necessarily the correct response to the growing disrespect and lawlessness that in the 1960s and 1970s saw crime rise... In this instance, we need less Jenkins and more Callaghan.

- Tony Blair, 2007 Callaghan Memorial Speech, quoted in 'Tony Blair – 2007 Callaghan Memorial Speech', UKPOL (12 September 2015)

- Roy Jenkins made a classic speech, which I contributed to, in which among other things he defined integration not as a flattening process which would turn everybody out in some kind of mould of a stereotyped Englishman but would be a combination of equal opportunities accompanied by cultural diversity in an atmosphere of tolerance.

- Anthony Lester, interview for "Rivers of Blood", BBC2 (8 March 2008), at 22:53

- I learned to admire his unflinching commitment to liberalism and his fastidiousness when it came to the corruption of language and ideas in modern public life. He was unquestionably a great man, and his biographies, as much as his political record, ensure that he will be remembered.

- Shirley Williams, Climbing the Bookshelves (2009), p. 386

2010s

[edit]- The model we had was that everyone would share the broad values of being British. What we did not expect was there would be those who unwisely suggest that, for example, Sharia Law should be applied in this country, or that punishment of stoning for adultery might be looked at depending on the kind of stoning ... It never occurred to us that there would be those kind of unwise challenges to the broad values of a liberal democratic society. And I remember towards the end of Roy Jenkins' life him saying to me that we just didn't realise that in the struggle for race equality we would also have to struggle for a secular society and for the universal value of human rights.

- Anthony Lester, quoted in Jasper Miles, ‘Social cohesion’, in Kevin Hickson (ed.), Rebuilding Social Democracy: Core Principles for the Centre Left (2016), pp. 84-85

- [Roy Jenkins] was one of the great figures in the Liberal and Social Democratic tradition in British politics. A great reforming home secretary, a much-admired chancellor, a great European and somebody whose values and life that in many ways I have followed

- Vince Cable, quoted in Elizabeth Glinka, 'Political heroes: Cable on Roy Jenkins', BBC News (23 February 2018)

- This was the era of Mary Whitehouse, an attempt to restore old fashioned values ... there was this enormous sort of mood, particularly amongst young people to sweep away all the rather old fashioned values which seemed to exist at that time ... and he, more than anybody else, lifted the barriers. It changed the face of the country, it modernised it, in a way that we would regard as perfectly normal today.

- Vince Cable, quoted in Elizabeth Glinka, 'Political heroes: Cable on Roy Jenkins', BBC News (23 February 2018)

External links

[edit]- 1920 births

- 2003 deaths

- Politicians from Wales

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

- Historians from Wales

- Biographers from the United Kingdom

- Labour Party (UK) politicians

- Liberal Democrats (UK) politicians

- Activists from Wales

- LGBT people

- University of Oxford alumni

- Presidents of the European Commission

- Chancellors of the Exchequer

- Home Secretaries (UK)