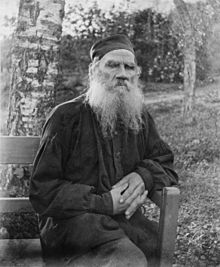

Leo Tolstoy

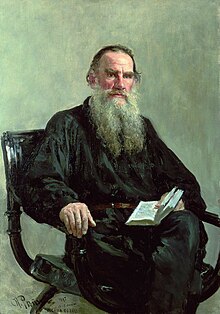

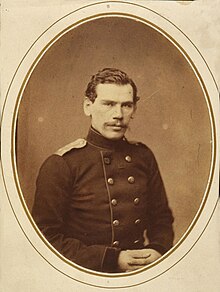

Lev Nikolayevitch Tolstoy [Ле́в Никола́евич Толсто́й, usually rendered Leo Tolstoy, or sometimes Tolstoi] (9 September 1828 – 20 November 1910) was a Russian writer, philosopher and social activist (social critic), whose novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina are internationally praised classics of world literature. He was a major influence on the development of Christian anarchism and pacifism, contributing to such nonviolent resistance movements as those of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Bevel.

Quotes

[edit]

God alone exists truly. Man manifests Him in time, space and matter.

- The hero of my tale, whom I love with all the power of my soul, whom I have tried to portray in all his beauty, who has been, is, and will be beautiful, is Truth.

- Sevastopol in May (1855), Ch. 16

- ...никогда Христос ... ни одним словом не утверждал личное воскресение и бессмертие личности за гробом...В чем моя вера?

- Translation: Never did Christ utter a single word attesting to a personal resurrection and a life beyond the grave.

- My Religion (1884), Ch. 8

- Error is the force that welds men together; truth is communicated to men only by deeds of truth. Only deeds of truth, by introducing light into the conscience of each individual, can dissolve the cohesion of error, and detach men one by one from the mass united together by the cohesion of error.

- My Religion (1884), Ch. 12

- I know that my unity with all people cannot be destroyed by national boundaries and government orders.

- My Religion (1884), as translated in The Human Experience : Contemporary American and Soviet Fiction and Poetry (1989) by the Quaker US/USSR Committee

- Martin's soul grew very very glad. He crossed himself put on his spectacles, and began reading the Gospel just where it had opened; and at the top of the page he read: I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat; I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink; I was a stranger, and ye took me in. And at the bottom of the page he read: Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of these my brethren even these least, ye did it unto me (Matt. xxv). And Martin understood that his dream had come true; and that the Saviour had really come to him that day, and he had welcomed him.

- "Where Love Is, God Is" (1885), also translated as "Where Love is, There God is Also" - (full text online)

- A man can live and be healthy without killing animals for food; therefore, if he eats meat, he participates in taking animal life merely for the sake of his appetite. And to act so is immoral.

- Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence (1886)

- I sit on a man's back, choking him, and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am very sorry for him and wish to ease his lot by any means possible, except getting off his back.

- Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence (1886)

- Six feet of land was all that he needed.

- The happiness of men consists in life. And life is in labor.

- What Is To Be Done? (1886) Chap. XXXVIII, as translated in The Novels and Other Works of Lyof N. Tolstoï (1902) edited by Nathan Haskell Dole, p. 259

- The vocation of every man and woman is to serve other people.

- What Is To Be Done? (1886) Chap. XL, as translated in The Novels and Other Works of Lyof N. Tolstoï (1902) edited by Nathan Haskell Dole, p. 281

- The more is given the less the people will work for themselves, and the less they work the more their poverty will increase.

- Help for the Starving, Pt. III (January 1892)

- Condemn me if you choose — I do that myself, — but condemn me, and not the path which I am following, and which I point out to those who ask me where, in my opinion, the path is.

- "Letter to N.N.," quoted by Havelock Ellis in "The New Spirit" (1892) p. 226

- In all history there is no war which was not hatched by the governments, the governments alone, independent of the interests of the people, to whom war is always pernicious even when successful.

The government assures the people that they are in danger from the invasion of another nation, or from foes in their midst, and that the only way to escape this danger is by the slavish obedience of the people to their government. This fact is seen most prominently during revolutions and dictatorships, but it exists always and everywhere that the power of the government exists. Every government explains its existence, and justifies its deeds of violence, by the argument that if it did not exist the condition of things would be very much worse. After assuring the people of its danger the government subordinates it to control, and when in this condition compels it to attack some other nation. And thus the assurance of the government is corroborated in the eyes of the people, as to the danger of attack from other nations.- Christianity and Patriotism (1895), as translated in The Novels and Other Works of Lyof N. Tolstoï, Vol. 20, p. 44

- Government is violence, Christianity is meekness, non-resistance, love. And, therefore, government cannot be Christian, and a man who wishes to be a Christian must not serve government.

- Letter to Dr. Eugen Heinrich Schmitt (October 12, 1896), translated by Nathan Haskell Dole

- Tell people that war is an evil, and they will laugh; for who does not know it? Tell them that patriotism is an evil, and most of them will agree, but with a reservation. "Yes," they will say, "wrong patriotism is an evil; but there is another kind, the kind we hold." But just what this good patriotism is, no one explains.

- Patriotism, or Peace? (1896), translated by Nathan Haskell Dole

- Variant:

- I have already several times expressed the thought that in our day the feeling of patriotism is an unnatural, irrational, and harmful feeling, and a cause of a great part of the ills from which mankind is suffering, and that, consequently, this feeling – should not be cultivated, as is now being done, but should, on the contrary, be suppressed and eradicated by all means available to rational men. Yet, strange to say – though it is undeniable that the universal armaments and destructive wars which are ruining the peoples result from that one feeling – all my arguments showing the backwardness, anachronism, and harmfulness of patriotism have been met, and are still met, either by silence, by intentional misinterpretation, or by a strange unvarying reply to the effect that only bad patriotism (Jingoism or Chauvinism) is evil, but that real good patriotism is a very elevated moral feeling, to condemn which is not only irrational but wicked.

What this real, good patriotism consists in, we are never told; or, if anything is said about it, instead of explanation we get declamatory, inflated phrases, or, finally, some other conception is substituted for patriotism – something which has nothing in common with the patriotism we all know, and from the results of which we all suffer so severely.- Patriotism and Government (1900)

- It will be said, "Patriotism has welded mankind into states, and maintains the unity of states." But men are now united in states; that work is done; why now maintain exclusive devotion to one's own state, when this produces terrible evils for all states and nations? For this same patriotism which welded mankind into states is now destroying those same states. If there were but one patriotism say of the English only then it were possible to regard that as conciliatory, or beneficent. But when, as now, there is American patriotism, English, German, French, Russian, all opposed to one another, in this event, patriotism no longer unites, but disunites.

- Patriotism and Government

- Understand that all the evils from which you suffer, you yourselves cause by yielding to the suggestions by which emperors, kings, members of parliament, governors, officers, capitalists, priests, authors, artists, and all who need this fraud of patriotism in order to live upon your labour, deceive you!

- Patriotism and Government

- If people would but understand that they are not the sons of some fatherland or other, nor of Governments, but are sons of God, and can therefore neither be slaves nor enemies one to another - those insane, unnecessary, worn-out, pernicious organizations called Governments, and all the sufferings, violations, humiliations and crimes which they occasion, would cease.

- Patriotism and Government

- The workmen's revolution, with the terrors of destruction and murder, not only threatens us, but we have already been living upon its verge during the last thirty years, and it is only by various cunning devices that we have been postponing the crisis... The hatred and contempt of the oppressed people are increasing, and the physical and moral strength of the richer classes are decreasing: the deceit which supports all this is wearing out, and the rich classes have nothing wherewith to comfort themselves.

- What is to be Done (1899) p. 262

- The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without authority, there could not be worse violence than that of authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. "To establish Anarchy." "Anarchy will be instituted." But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require protection from governmental power, and by there being more and more people who will be ashamed of applying this power.

- "On Anarchy", in Pamphlets : Translated from the Russian (1900) as translated by Aylmer Maude, p. 22

- There can be only one permanent revolution — a moral one; the regeneration of the inner man.

How is this revolution to take place? Nobody knows how it will take place in humanity, but every man feels it clearly in himself. And yet in our world everybody thinks of changing humanity, and nobody thinks of changing himself.- "Three Methods Of Reform" in Pamphlets : Translated from the Russian (1900) as translated by Aylmer Maude, p. 29

- Variant: Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

- As quoted in The Artist's Way at Work : Riding the Dragon (1999) by Mark A. Bryan with Julia Cameron and Catherine A. Allen, p. 160

- Every one who has a heart and eyes sees that you, working men, are obliged to pass your lives in want and in hard labor, which is useless to you, while other men, who do not work, enjoy the fruits of your labor—that you are the slaves of these men, and that this ought not to exist.

- "To the Working People," Complete Works, trans. Leo Wiener, Vol 24, p. 129 (1905)

- Not only does the action of Governments not deter men from crimes; on the contrary, it increases crime by always disturbing and lowering the moral standard of society. Nor can this be otherwise, since always and everywhere a Government, by its very nature, must put in the place of the highest, eternal, religious law (not written in books but in the hearts of men, and binding on every one) its own unjust, man-made laws, the object of which is neither justice nor the common good of all but various considerations of home and foreign expediency.

- The Meaning of the Russian Revolution (1906), a work about the 1905 Russian Revolution.

- One might think that it must be quite clear to people not deprived of reason, that violence breeds violence; that the only means of deliverance from violence lies in not taking part in it. This method, one would think, is quite obvious. It is evident that a great majority of men can be enslaved by a small minority only if the enslaved themselves take part in their own enslavement. If people are enslaved, it is only because they either fight violence with violence or participate in violence for their own personal profit. Those who neither struggle against violence nor take part in it can no more be enslaved than water can be cut. They can be robbed, prevented from moving about, wounded or killed, but they cannot be enslaved: that is, made to act against their own reasonable will.

- All violence consists in some people forcing others, under threat of suffering or death, to do what they do not want to do.

- Understand then all of you, especially the young, that to want to impose an imaginary state of government on others by violence is not only a vulgar superstition, but even a criminal work. Understand that this work, far from assuring the well-being of humanity is only a lie, a more or less unconscious hypocrisy, camouflaging the lowest passions we possess.

- Passage written for for The Law of Love and the Law of Violence (1908), released in 1917, as quoted in Equality in Liberty and Justice (2001) by Antony Flew, p. 89

- God is the infinite ALL. Man is only a finite manifestation of Him.

Or better yet:

God is that infinite All of which man knows himself to be a finite part.

God alone exists truly. Man manifests Him in time, space and matter. The more God's manifestation in man (life) unites with the manifestations (lives) of other beings, the more man exists. This union with the lives of other beings is accomplished through love.

God is not love, but the more there is of love, the more man manifests God, and the more he truly exists...

We acknowledge God only when we are conscious of His manifestation in us. All conclusions and guidelines based on this consciousness should fully satisfy both our desire to know God as such as well as our desire to live a life based on this recognition.- Entry in Tolstoy's Diary (1 November 1910)

- Men think it right to eat animals, because they are led to believe that God sanctions it. This is untrue. No matter in what books it may be written that it is not sinful to slay animals and to eat them, it is more clearly written in the heart of man than in any books that animals are to be pitied and should not be slain any more than human beings. We all know this if we do not choke the voice of our conscience.

- The Pathway of Life: Teaching Love and Wisdom (posthumous), Part I, International Book Publishing Company, New York, 1919, p. 68

- How good is it to remember one's insignificance: that of a man among billions of men, of an animal amid billions of animals; and one's abode, the earth, a little grain of sand in comparison with Sirius and others, and one's life span in comparison with billions on billions of ages. There is only one significance, you are a worker. The assignment is inscribed in your reason and heart and expressed clearly and comprehensibly by the best among the beings similar to you. The reward for doing the assignment is immediately within you. But what the significance of the assignment is or of its completion, that you are not given to know, nor do you need to know it. It is good enough as it is. What else could you desire?

- Last Diaries (1979) edited by Leon Stilman, p. 77

- People usually think that progress consists in the increase of knowledge, in the improvement of life, but that isn't so. Progress consists only in the greater clarification of answers to the basic questions of life. The truth is always accessible to a man. It can't be otherwise, because a man's soul is a divine spark, the truth itself. It's only a matter of removing from this divine spark (the truth) everything that obscures it. Progress consists, not in the increase of truth, but in freeing it from its wrappings. The truth is obtained like gold, not by letting it grow bigger, but by washing off from it everything that isn't gold.

- Tolstoy's Diaries (1985) edited and translated by R. F. Christian. London: Athlone Press, Vol 2, p. 512

- The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.

- As quoted in Tolstoy (1988) by A. N. Wilson, p. 146

- Science is meaningless because it gives no answer to our question, the only question important for us: 'what shall we do and how shall we live

- Quoted by Max Weber in his lecture "Science as a Vocation"; in Lynda Walsh (2013), Scientists as Prophets: A Rhetorical Genealogy (2013), Oxford University Press, p. 90

Family Happiness (1859)

[edit]- I longed for activity, instead of an even flow of existence. I wanted excitement and danger and the chance to renounce self for the sake of my love. I was conscious of a superabundance of energy which found no outlet in our quiet life. I had bouts of depression, which I tried to hide, as something to be ashamed of...My mind, even my senses were occupied, but there was another feeling – the feeling of youth and a craving for activity – which found no scope in our quiet life...So time went by, the snow piled higher and higher round the house, and there we remained together, always and for ever alone and just the same in each other's eyes; while somewhere far away amidst glitter and noise multitudes of people thrilled, suffered and rejoiced, without one thought of us and our existence which was ebbing away. Worst of all, I felt that every day that passed riveted another link to the chain of habit which was binding our life into a fixed shape, that our emotions, ceasing to be spontaneous, were being subordinated to the even, passionless flow of time... 'It's all very well ... ' I thought, 'it's all very well to do good and lead upright lives, as he says, but we'll have plenty of time for that later, and there are other things for which the time is now or never.' I wanted, not what I had got, but a life of challenge; I wanted feeling to guide us in life, and not life to guide us in feeling.

- There is only one enduring happiness in life—to live for others.

- I have lived through much, and now I think I have found what is needed for happiness. A quiet secluded life in the country, with the possibility of being useful to people to whom it is easy to do good, and who are not accustomed to have it done to them; then work which one hopes may be of some use; then rest, nature, books, music, love for one's neighbor -- such is my idea of happiness. And then, on the top of all that, you for a mate, and children perhaps -- what more can the heart of man desire?

War and Peace (1865–1867; 1869)

[edit]

- Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Buonapartes. But I warn you, if you don't tell me that this means war, if you still try to defend the infamies and horrors perpetrated by that Antichrist—I really believe he is Antichrist—I will have nothing more to do with you and you are no longer my friend, no longer my 'faithful slave,' as you call yourself! But how do you do? I see I have frightened you—sit down and tell me all the news.

- Bk. I, Ch. I

- Now about your family. Do you know that since your daughter came out everyone has been enraptured by her? They say she is amazingly beautiful.

- Bk. I, Ch. I

- Each visitor performed the ceremony of greeting this old aunt whom not one of them knew, not one of them wanted to know, and not one of them cared about; Anna Pávlovna observed these greetings with mournful and solemn interest and silent approval. The aunt spoke to each of them in the same words, about their health and her own, and the health of Her Majesty, "who, thank God, was better today." And each visitor, though politeness prevented his showing impatience, left the old woman with a sense of relief at having performed a vexatious duty and did not return to her the whole evening.

- Bk. I, Ch. II

- The young Princess Bolkónskaya had brought some work in a gold-embroidered velvet bag. Her pretty little upper lip, on which a delicate dark down was just perceptible, was too short for her teeth, but it lifted all the more sweetly, and was especially charming when she occasionally drew it down to meet the lower lip. As is always the case with a thoroughly attractive woman, her defect—the shortness of her upper lip and her half-open mouth—seemed to be her own special and peculiar form of beauty. Everyone brightened at the sight of this pretty young woman, so soon to become a mother, so full of life and health, and carrying her burden so lightly. Old men and dull dispirited young ones who looked at her, after being in her company and talking to her a little while, felt as if they too were becoming, like her, full of life and health. All who talked to her, and at each word saw her bright smile and the constant gleam of her white teeth, thought that they were in a specially amiable mood that day.

- Bk. I, Ch. II

- Anna Pávlovna's reception was in full swing. The spindles hummed steadily and ceaselessly on all sides. With the exception of the aunt, beside whom sat only one elderly lady, who with her thin careworn face was rather out of place in this brilliant society, the whole company had settled into three groups. One, chiefly masculine, had formed round the abbé. Another, of young people, was grouped round the beautiful Princess Hélène, Prince Vasíli's daughter, and the little Princess Bolkónskaya, very pretty and rosy, though rather too plump for her age. The third group was gathered round Mortemart and Anna Pávlovna.

- Bk. I, Ch. III

- The vicomte was a nice-looking young man with soft features and polished manners, who evidently considered himself a celebrity but out of politeness modestly placed himself at the disposal of the circle in which he found himself. Anna Pávlovna was obviously serving him up as a treat to her guests. As a clever maître d'hôtel serves up as a specially choice delicacy a piece of meat that no one who had seen it in the kitchen would have cared to eat, so Anna Pávlovna served up to her guests, first the vicomte and then the abbé, as peculiarly choice morsels. The group about Mortemart immediately began discussing the murder of the Duc d'Enghien. The vicomte said that the Duc d'Enghien had perished by his own magnanimity, and that there were particular reasons for Buonaparte's hatred of him.

- Bk. I, Ch. III

- Just then another visitor entered the drawing room: Prince Andrew Bolkónski, the little princess' husband. He was a very handsome young man, of medium height, with firm, clearcut features. Everything about him, from his weary, bored expression to his quiet, measured step, offered a most striking contrast to his quiet, little wife. It was evident that he not only knew everyone in the drawing room, but had found them to be so tiresome that it wearied him to look at or listen to them. And among all these faces that he found so tedious, none seemed to bore him so much as that of his pretty wife. He turned away from her with a grimace that distorted his handsome face, kissed Anna Pávlovna's hand, and screwing up his eyes scanned the whole company.

- Bk. I, Ch. IV

- Pierre, who from the moment Prince Andrew entered the room had watched him with glad, affectionate eyes, now came up and took his arm. Before he looked round Prince Andrew frowned again, expressing his annoyance with whoever was touching his arm, but when he saw Pierre's beaming face he gave him an unexpectedly kind and pleasant smile. "There now!... So you, too, are in the great world?" said he to Pierre. "I knew you would be here," replied Pierre. "I will come to supper with you. May I?" he added in a low voice so as not to disturb the vicomte who was continuing his story. "No, impossible!" said Prince Andrew, laughing and pressing Pierre's hand to show that there was no need to ask the question. He wished to say something more, but at that moment Prince Vasíli and his daughter got up to go and the two young men rose to let them pass.

- Bk. I, Ch. IV

- "What's this? Am I falling? My legs are giving way under me," he thought, and fell on his back. He opened his eyes, hoping to see how the struggle of the French soldiers with the artilleryman was ending, and eager to know whether the red-haired gunner artilleryman was killed or not, whether the cannons had been taken or saved. But he saw nothing of all that. Above him there was nothing but the sky — the lofty sky, not clear, but still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds creeping quietly over it.

- Bk. III, Ch. 16

- Three days later the little princess was buried, and Prince Andrei went up the steps to where the coffin stood, to give her the farewell kiss. And there in the coffin was the same face, though with closed eyes. "Ah, what have you done to me?" it still seemed to say, and Prince Andrei felt that something gave way in his soul and that he was guilty of a sin he could neither remedy nor forget.

- Bk. IV, Ch. 9

- Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly. It is the one thing we are interested in here.

- Book IV, Ch. 11

- You will die — and it will all be over. You will die and find out everything — or cease asking.

- Bk. V, Ch. 1

- The only thing that we know is that we know nothing — and that is the highest flight of human wisdom.

- Book V, Ch. I

- It is not sufficient to observe our mysteries in the seclusion of our lodge—we must act—act! We are drowsing, but we must act. (Pierre raised his notebook and began to read.) For the dissemination of pure truth and to secure the triumph of virtue," he read, "we must cleanse men from prejudice, diffuse principles in harmony with the spirit of the times, undertake the education of the young, unite ourselves in indissoluble bonds with the wisest men, boldly yet prudently overcome superstitions, infidelity, and folly, and form of those devoted to us a body linked together by unity of purpose and possessed of authority and power.

- To attain this end we must secure a preponderance of virtue over vice and must endeavor to secure that the honest man may, even in this world, receive a lasting reward for his virtue. But in these great endeavors we are gravely hampered by the political institutions of today. What is to be done in these circumstances? To favor revolutions, overthrow everything, repel force by force?... No! We are very far from that. Every violent reform deserves censure, for it quite fails to remedy evil while men remain what they are, and also because wisdom needs no violence.

- Book V, Ch. 7

- The whole plan of our order should be based on the idea of preparing men of firmness and virtue bound together by unity of conviction—aiming at the punishment of vice and folly, and patronizing talent and virtue: raising worthy men from the dust and attaching them to our Brotherhood. Only then will our order have the power unobtrusively to bind the hands of the protectors of disorder and to control them without their being aware of it. In a word, we must found a form of government holding universal sway, which should be diffused over the whole world without destroying the bonds of citizenship, and beside which all other governments can continue in their customary course and do everything except what impedes the great aim of our order, which is to obtain for virtue the victory over vice

- Book VI, Chapter VII

- He received me graciously... I made the sign of the Knights of the East and of Jerusalem, and he responded in the same manner, asking me with a mild smile what I had learned and gained in the Prussian and Scottish lodges. I told him everything as best I could, and told him what I had proposed to our Petersburg lodge, of the bad reception I had encountered, and of my rupture with the Brothers. Joseph Alexéevich, having remained silent and thoughtful for a good while, told me his view of the matter, which at once lit up for me my whole past and the future path I should follow. He surprised me by asking whether I remembered the threefold aim of the order: (1) The preservation and study of the mystery. (2) The purification and reformation of oneself for its reception, and (3) The improvement of the human race by striving for such purification. Which is the principal aim of these three? Certainly self-reformation and self-purification. Only to this aim can we always strive independently of circumstances. But at the same time just this aim demands the greatest efforts of us; and so, led astray by pride, losing sight of this aim, we occupy ourselves either with the mystery which in our impurity we are unworthy to receive, or seek the reformation of the human race while ourselves setting an example of baseness and profligacy. Illuminism is not a pure doctrine, just because it is attracted by social activity and puffed up by pride. On this ground Joseph Alexéevich condemned my speech and my whole activity, and in the depth of my soul I agreed with him.

- Book VI, Chapter VIII

- In historical events great men — so-called — are but labels serving to give a name to the event, and like labels they have the least possible connection with the event itself. Every action of theirs, that seems to them an act of their own free will, is in an historical sense not free at all, but in bondage to the whole course of previous history, and predestined from all eternity.

- Bk. IX, ch. 1

- A king is history's slave.

- Bk. IX, ch. 1

- A Frenchman is self-assured because he regards himself personally, both in mind and body, as irresistibly attractive to men and women. An Englishman is self-assured, as being a citizen of the best-organized state in the world, and therefore as an Englishman always knows what he should do and knows that all he does as an Englishman is undoubtedly correct. An Italian is self-assured because he is excitable and easily forgets himself and other people. A Russian is self-assured just because he knows nothing and does not want to know anything, since he does not believe that anything can be known. The German's self-assurance is worst of all, stronger and more repulsive than any other, because he imagines that he knows the truth — science — which he himself has invented but which is for him the absolute truth.

- Bk. IX, ch. 10

- Everything comes in time to him who knows how to wait.

- Bk. X, ch. 16

- The strongest of all warriors are these two — Time and Patience.

- Bk. X, ch. 16

- At the approach of danger there are always two voices that speak with equal force in the heart of man: one very reasonably tells the man to consider the nature of the danger and the means of avoiding it; the other even more reasonable says that it is too painful and harassing to think of the danger, since it is not a man's power to provide for everything and escape from the general march of events; and that it is therefore better to turn aside from the painful subject till it has come, and to think of what is pleasant. In solitude a man generally yields to the first voice; in society to the second.

- Bk. X, ch. 17

- War is not a courtesy but the most horrible thing in life; and we ought to understand that, and not play at war. We ought to accept this terrible necessity sternly and seriously. It all lies in that: get rid of falsehood and let war be war and not a game. As it is now, war is the favourite pastime of the idle and frivolous.

- Bk. X, ch. 25

- He did not, and could not, understand the meaning of words apart from their context. Every word and action of his was the manifestation of an activity unknown to him, which was his life.

- About Platon Karataev in Bk. XII, ch. 13

- Love hinders death. Love is life. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love. Everything is united by it alone. Love is God, and to die means that I, a particle of love, shall return to the general and eternal source.

- Thoughts of Prince Andrew Bk XII, Ch. 16

- “They must understand that we can only lose by taking the offensive. Patience and time are my warriors, my champions,” thought Kutúzov. He knew that an apple should not be plucked while it is green. It will fall of itself when ripe, but if picked unripe the apple is spoiled, the tree is harmed, and your teeth are set on edge.

- Bk XIII, Ch. 17

- While imprisoned in the shed Pierre had learned not with his intellect but with his whole being, by life itself, that man is created for happiness, that happiness is within him, in the satisfaction of simple human needs, and that all unhappiness arises not from privation but from superfluity. And now during these last three weeks of the march he had learned still another new, consolatory truth- that nothing in this world is terrible. He had learned that as there is no condition in which man can be happy and entirely free, so there is no condition in which he need be unhappy and lack freedom. He learned that suffering and freedom have their limits and that those limits are very near together....

- Bk. XIV, ch. 12

- To love life is to love God. Harder and more blessed than all else is to love this life in one's sufferings, in undeserved sufferings.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 15

- For us, with the rule of right and wrong given us by Christ, there is nothing for which we have no standard. And there is no greatness where there is not simplicity, goodness, and truth.

- Bk. XIV, ch. 18

- Pure and complete sorrow is as impossible as pure and complete joy.

- Bk. XV, ch. 1

- Despite the fact that the doctors treated him, bled him, and gave him medicines to drink, he recovered.

[sometimes quoted as "Though the doctors treated him, let his blood, and gave him medications to drink, he nevertheless recovered."]- Bk. XV, ch. 12

- History is the life of nations and of humanity. To seize and put into words, to describe directly the life of humanity or even of a single nation, appears impossible.

- The peculiar and amusing nature of those answers stems from the fact that modern history is like a deaf person who is in the habit of answering questions that no one has put to them.

If the purpose of history be to give a description of the movement of humanity and of the peoples, the first question — in the absence of a reply to which all the rest will be incomprehensible — is: what is the power that moves peoples? To this, modern history laboriously replies either that Napoleon was a great genius, or that Louis XIV was very proud, or that certain writers wrote certain books.

All that may be so and mankind is ready to agree with it, but it is not what was asked.- Vol 2, pt 5, p 236 — Selected Works, Moscow, 1869

Anna Karenina (1875–1877; 1878)

[edit]

- Vengeance is mine; I will repay.

- Epigraph

- Все счастливые семьи похожи друг на друга, каждая несчастливая семья несчастлива по-своему.

- All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- Pt. I, ch. 1

- Variant translations: Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

All happy families resemble one another; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- There was no answer, except the general answer life gives to all the most complex and insoluble questions. That answer is: one must live for the needs of the day, in other words, become oblivious. To become oblivious in dreams was impossible now, at least till night-time; it was impossible to return to that music sung by carafe-women; and so one had to become oblivious in the dreams of life.

- Pt. 1, ch. 2

- Stephan Arkadievich chose neither his attitudes nor his opinions, no, the attitudes and opinions came to him on their own, just as he chose neither the style of his hat nor of his coats but got what people were wearing.

- Part 1, Chapter 3

- He knew she was there by the joy and fear that overwhelmed his heart.

- Pt. I, ch. 9

- He stepped down, trying not to look long at her, as if she were the sun, yet he saw her, like the sun, even without looking.

- Pt. I, ch. 9

- All his life Alexey Alexandrovitch had lived and worked in official spheres, having to do with the reflection of life. And every time he had stumbled against life itself he had shrunk away from it. Now he experienced a feeling akin to that of a man who, wile calmly crossing a precipice by a bridge, should suddenly discover that the bridge is broken, and that there is a chasm below. That chasm was life itself, the bridge that artificial life in which Alexey Alexandrovitch had lived.

- Part II, Chapter 8

- Vronsky, meanwhile, in spite of the complete realization of what he had so long desired, was not perfectly happy. He soon felt that the realization of his desires gave him no more than a grain of sand out of the mountain of happiness he had expected. It showed him the mistake men make in picturing to themselves happiness as the realization of their desires. For a time after joining his life to hers, and putting on civilian dress, he had felt all the delight of freedom in general, of which he had known nothing before, and of freedom in his love — and he was content, but not for long. He was soon aware that there was springing up in his heart a desire for desires — longing. Without conscious intention he began to clutch at every passing caprice, taking it for a desire and an object.

- There was something in her higher than what surrounded her. There was in her the glow of the real diamond among glass imitations. This glow shone out in her exquisite, truly enigmatic eyes. The weary, and at the same time passionate, glance of those eyes, encircled by dark rings, impressed one by its perfect sincerity. Everyone looking into those eyes fancied he knew her wholly, and knowing her, could not but love her.

- Anna's thoughts about Liza, Part III, Chapter 13

- "If you want him defined, here he is: a prime, well-fed beast such as takes medals at the cattle shows, and nothing more," he said, with a tone of vexation that interested her.

"No; how so?" she replied. "He's seen a great deal, anyway; he's cultured?"

"It's an utterly different culture—their culture. He's cultivated, one sees, simply to be able to despise culture, as they despise everything but animal pleasures."- Vronky and Anna discussing the visiting Prince, Part 4, Chapter 3

- One can insult an honest man or an honest woman, but to tell a thief that he is a thief is merely la constation d'un fait [The establishing of a fact.]

- Pt. IV, ch. 4

- The new commission for the inquiry into the condition of the native tribes in all its branches had been formed and dispatched to its destination with an unusual speed and energy inspired by Alexey Alexandrovitch. Within three months a report was presented. The condition of the native tribes was investigated in its political, administrative, economic, ethnographic, material, and religious aspects. To all these questions there were answers admirably stated, and answers admitting no shade of doubt, since they were not a product of human thought, always liable to error, but were all the product of official activity. The answers were all based on official data furnished by governors and heads of churches, and founded on the reports of district magistrates and ecclesiastical superintendents, founded in their turn on the reports of parochial overseers and parish priests; and so all of these answers were unhesitating and certain. All such questions as, for instance, of the cause of failure of crops, of the adherence of certain tribes to their ancient beliefs, etc.—questions which, but for the convenient intervention of the official machine, are not, and cannot be solved for ages—received full, unhesitating solution.

- Part IV, Chapter 6

- "Respect was invented to cover the empty place where love should be."

- (voice of Anna) C. Garnett, trans. (New York: 2003), Part 7, Chapter 24 p. 685

- Reason has discovered the struggle for existence and the law that I must throttle all those who hinder the satisfaction of my desires. That is the deduction reason makes. But the law of loving others could not be discovered by reason, because it is unreasonable.

- Pt. VIII, ch. 13

- There is one evident, indubitable manifestation of the Divinity, and that is the laws of right which are made known to the world through Revelation.

- Pt. VIII, ch. 19

- My reason will still not understand why I pray, but I shall still pray, and my life, my whole life, independently of anything that may happen to me, is every moment of it no longer meaningless as it was before, but has an unquestionable meaning of goodness with which I have the power to invest it.'

- Pt. VIII, ch. 19

What Men Live By (1881)

[edit]- Go — take the mother's soul, and learn three truths: Learn What dwells in man, What is not given to man, and What men live by. When thou hast learnt these things, thou shalt return to heaven.

- Ch. IV

- I thought: "I am perishing of cold and hunger, and here is a man thinking only of how to clothe himself and his wife, and how to get bread for themselves. He cannot help me. When the man saw me he frowned and became still more terrible, and passed me by on the other side. I despaired, but suddenly I heard him coming back. I looked up, and did not recognize the same man: before, I had seen death in his face; but now he was alive, and I recognized in him the presence of God.

- Then I remembered the first lesson God had set me: "Learn what dwells in man." And I understood that in man dwells Love! I was glad that God had already begun to show me what He had promised, and I smiled for the first time.

- Ch. XI

- The man is making preparations for a year, and does not know that he will die before evening. And I remembered God's second saying, "Learn what is not given to man."

'What dwells in man" I already knew. Now I learnt what is not given him. It is not given to man to know his own needs.- Ch. XI

- When the woman showed her love for the children that were not her own, and wept over them, I saw in her the living God, and understood What men live by.

- Ch. XI

- And the angel's body was bared, and he was clothed in light so that eye could not look on him; and his voice grew louder, as though it came not from him but from heaven above. And the angel said:

I have learnt that all men live not by care for themselves, but by love.

It was not given to the mother to know what her children needed for their life. Nor was it given to the rich man to know what he himself needed. Nor is it given to any man to know whether, when evening comes, he will need boots for his body or slippers for his corpse.

I remained alive when I was a man, not by care of myself, but because love was present in a passer-by, and because he and his wife pitied and loved me. The orphans remained alive, not because of their mother's care, but because there was love in the heart of a woman a stranger to them, who pitied and loved them. And all men live not by the thought they spend on their own welfare, but because love exists in man.

I knew before that God gave life to men and desires that they should live; now I understood more than that.

I understood that God does not wish men to live apart, and therefore he does not reveal to them what each one needs for himself; but he wishes them to live united, and therefore reveals to each of them what is necessary for all.

I have now understood that though it seems to men that they live by care for themselves, in truth it is love alone by which they live. He who has love, is in God, and God is in him, for God is love.- Ch. XII

Confession (1882)

[edit]

- Quite often a man goes on for years imagining that the religious teaching that had been imparted to him since childhood is still intact, while all the time there is not a trace of it left in him.

- Pt. I, ch. 1

- I cannot recall those years without horror, loathing, and heart-rending pain. I killed people in war, challenged men to duels with the purpose of killing them, and lost at cards; I squandered the fruits of the peasants' toil and then had them executed; I was a fornicator and a cheat. Lying, stealing, promiscuity of every kind, drunkenness, violence, murder — there was not a crime I did not commit... Thus I lived for ten years.

- Pt. I, ch. 2

- Several times I asked myself, "Can it be that I have overlooked something, that there is something which I have failed to understand? Is it not possible that this state of despair is common to everyone?" And I searched for an answer to my questions in every area of knowledge acquired by man. For a long time I carried on my painstaking search; I did not search casually, out of mere curiosity, but painfully, persistently, day and night, like a dying man seeking salvation. I found nothing.

- Pt. I, ch. 5

- One can only live while one is intoxicated with life; as soon as one is sober it is impossible not to see that it is all a mere fraud and a stupid fraud!

- Ch. 4

- Variant: It is possible to live only as long as life intoxicates us; once we are sober we cannot help seeing that it is all a delusion, a stupid delusion.

- The only absolute knowledge attainable by man is that life is meaningless.

- Ch. 5, translated by David Patterson, 1983

- For man to be able to live he must either not see the infinite, or have such an explanation of the meaning of life as will connect the finite with the infinite.

What I Believe (1885)

[edit]- As long as there are slaughterhouses there will always be battlefields.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886)

[edit]- Ivan Ilych's life had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore most terrible.

- Ch. II

- Ivan Ilych saw that he was dying, and he was in continual despair. In the depth of his heart he knew he was dying, but not only was he not accustomed to the thought, he simply did not and could not grasp it. The syllogism he had learnt from Kiesewetter's Logic: "Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal," had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius — man in the abstract — was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius, not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others.

- Ch. VI

- It occurred to him that what had appeared perfectly impossible before, namely that he had not spent his life as he should have done, might after all be true. It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false. And his professional duties and the whole arrangement of his life and of his family, and all his social and official interests, might all have been false. He tried to defend all those things to himself and suddenly felt the weakness of what he was defending.

- Ch. XI

What then must we do? (1886)

[edit]- The unhappiness of our life; patch up our false way of life as we will, propping it up by the aid of the sciences and arts - that life becomes feebler, sicklier, and more tormenting every year; every year the number of suicides and the avoidance of motherhood increases; every year the people of that class become feebler; every year we feel the increasing gloom of our lives. Evidently salvation is not to be found by increasing the comforts and pleasures of life, medical treatments, artificial teeth and hair, breathing exercises, massage, and so forth;...It is impossible to remedy this by any amusements, comforts, or powders - it can only be remedied by a change of life.

- The conscience of a man of our circle, if he retains but a scrap of it, cannot rest, and poisons all the comforts and enjoyments of life supplied to us by the labour of our brothers, who suffer and perish at that labour. And not only does every conscientious man feel this himself (he would be glad to forget it, but cannot do so in our age) but all the best part of science and art - that part which has not forgotten the purpose of its vocation - continually reminds us of our cruelty and of our unjustifiable position. The old firm justifications are all destroyed; the new ephemeral justifications of the progress of science for science's sake and art for art's sake do not stand the light of simple common sense. Men's consciences cannot be set at rest by new excuses, but only by a change of life which will make any justification of oneself unnecessary as there will be nothing needing justification.

- When I started life Hegelianism was the basis of everything: it was in the air, found expression in magazine and newspaper articles, in novels and essays, in art, in histories, in sermons, and in conversation. A man unacquainted with Hegel had no right to speak: he who wished to know the truth studied Hegel. Everything rested on him; and suddenly forty years have gone by and there is nothing left of him, he is not even mentioned — as though he had never existed. And what is most remarkable is that, like pseudo-Christianity, Hegelianism fell not because anyone refuted it, but because it suddenly became evident that neither the one nor the other was needed by our learned, educated world.

- Chapter XXIX

- Is not the reason of the confidence of the positive, critical, experimental scientists, and of the reverent attitude of the crowd towards their doctrines, still the same? At first it seems strange how the theory of evolution (which, like the redemption in theology, serves the majority as a popular expression of the whole new creed) can justify people in their injustice, and it seems as if the scientific theory dealt only with facts and did nothing but observe facts. But that only seems so. It seemed just the same in the case of theological doctrine: theology, it seemed, was only occupied with dogmas and had no relation to people's lives, and it seemed the same with regard to philosophy, which appeared to be occupied solely with transcendental reasonings. But that only seemed so. It was just the same with the Hegelian doctrine on a large scale and with the particular case of the Malthusian teaching.

- The positivist philosophy of Comte and the I doctrine deduced from it that humanity is an organism, and Darwin's doctrine of a law of the struggle for existence that is supposed to govern life, with the differentiation of various breeds of people which follows from it, and the anthropology, biology, and sociology of which people are now so fond-all have the same aim. These have all become favourite sciences because they serve to justify the way in which people free themselves from the human obligation to labour, while consuming the fruits of other people's labour.

- This new fraud is just like the old ones: its essence lies in substituting something external for the use of our own reason and conscience and that of our predecessors: in the Church teaching this external thing was revelation, in the scientific teaching it is observation. The trick played by this science is to destroy man's faith in reason and conscience by directing attention to the grossest deviations from the use of human reason and conscience, and having clothed the deception in a scientific theory, to assure them that by acquiring knowledge of external phenomena they will get to know indubitable facts which will reveal to them the law of man's life. And the mental demoralization consists in this, that coming to believe that things which should be decided by conscience and reason are decided by observation, these people lose their consciousness of good and evil and become incapable of understanding the expression and definitions of good and evil that have been formed by the whole preceding life of humanity. All this, in their jargon, is conditional and subjective. It must all be abandoned - they say - the truth cannot be understood by one's reason, for one may err, but there is another path which is infallible and almost mechanical: one must study facts. And facts must be studied on the basis of the scientists' science, that is, on the basis of two unfounded propositions: positivism and evolution which are put forward as indubitable truths. And the reigning science, with not less misleading solemnity than the Church, announces that the solution of all questions of life is only possible by the study of the facts of nature, and especially of organisms. A frivolous crowd of youths mastered by the novelty of this authority, which is as yet not merely not destroyed but not even touched by criticism, throws itself into the study of these facts of natural science as the sole path which, according to the assertions of the prevailing doctrine, can lead to the elucidation of the questions of life. But the further these disciples advance in this study the further and further are they removed not only from the possibility but even from the very thought of solving life's problems, and the more they become accustomed not so much to observe as to take on trust what they are told of the observations of others (to believe in cells, in protoplasm, in the fourth state of matter,1 &c.), the more and more does the form hide the contents from them; the more and more do they lose consciousness of good and evil and capacity to understand the expressions and definitions of good and evil worked out by the whole preceding life of humanity; the more and more do they adopt the specialized scientific jargon of conventional expressions which have no general human significance; the farther and farther do they wander among the debris of quite unilluminated observations; the more and more do they lose capacity not only to think independently but even to under-stand another man's fresh human thought lying outside their Talmud; and, what is most important, they pass their best years in growing unaccustomed to life, that is, to labour, and grow accustomed to consider their condition justified, while they become physically good-for-nothing parasites. And just like the theologians and the Talmudists they completely castrate their brains and become eunuchs of thought. And just like them, to the degree to which they become stupefied, they acquire a self-confidence which deprives them for ever of the possibility of returning to a simple clear and human way of thinking.

- Science has adapted itself entirely to the wealthy classes and accordingly has set itself to heal those who can afford everything, and it prescribes the same methods for those who have nothing to spare.

- Science may fall back on its stupid excuse that science works for science, and that when it has been developed by the scientists it will become accessible to the people also; but art, if it be art, should be accessible to all, and particularly to those for whom it is produced. And the position of our art strikingly arraigns the producers of art for not wishing, not knowing how, and being unable, to serve the people.

- Service of the people by sciences and arts will only exist when men live with the people and as the people live, and without presenting any claims will offer their scientific and artistic services, which the people will be free to accept or decline as they please.

- To say that the activity of science and art helps humanity's progress, if by that activity we mean the activity which now calls itself by those names, is as though one said that the clumsy, obstructive splashing of oars in a boat moving down stream assists the boat's progress. It only hinders it... The proof of this is seen in the confession made by men of science that the achievements of the arts and sciences are inaccessible to the labouring masses on account of the unequal distribution of wealth.

- 'BUT science and art! You are denying science and art: that is you are denying that by which humanity lives.' People constantly make this rejoinder to me, and they employ: this method in order to reject my arguments without examination. 'He rejects science and art, he wishes man to revert to a state of savagery - why listen to him or discuss with him?' But this is unjust. Not only do I not repudiate science, that is, the reasonable activity of humanity, and art - the expression of that reasonable activity - but it is just on behalf of that reasonable activity and its expression that I speak, only that It may be possible for mankind to escape from the savage state into which it is rapidly lapsing thanks to the false teaching of our time. It is only on that account that I speak as I do.

- A real mother, who knows the will of God by experience, will prepare her children also to fulfil it. Such a mother will suffer if she sees her child overfed, effeminate, and dressed-up, for she knows that these things will make it difficult for it to fulfil the will of God which she recognizes.

- If there may be doubts for men and for a childless woman as to the way to, fulfil the will of God, for a mother that path is firmly and clearly defined, and if she fulfils it humbly with a simple heart she stands on the highest point of perfection a human being can attain, and becomes for all a model of that complete performance of God's will which all desire. Only a mother can before her death tranquilly say to Him who sent her into this world, and Whom she has served by bearing and bringing up children whom she has loved more than herself - only she having served Him in the way appointed to her can say with tranquillity, Now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace. And that is the highest perfection to which, as to the highest good, men aspire.

The Kreutzer Sonata (1889)

[edit]- If one has no vanity in this life of ours, there is no sufficient reason for living.

- Ch. 23. This is not, as it is often quoted, a stand-alone Tolstoy epigram, but part of the narration by the novella's jealousy-ridden protagonist Pozdnyshev.

The Slavery of Our Times (1890)

[edit]

- The condition of life to which people of the well-to-do classes are accustomed is that of an abundant production of various articles necessary for their comfort and pleasure, and these things are obtained only thanks to the existence of factories and works organized as at present. And, therefore, discussing the improvement of the workers' position, the men of science belonging to the well- to-do classes always have in view only such improvements as will not do away with the system of factory-production and those conveniences of which they avail themselves.

- Chapter V: Why Learned Economists Assert What Is False

- If the slave-owner of our times has no slave, John, whom he can send to the cesspool, he has five shillings, of which hundreds of such Johns are in such need that the slave-owner of our times may choose any one out of hundreds of Johns and be a benefactor to him by giving him the preference, and allowing him, rather than another, to climb down into the cesspool.

- Chapter 8: Slavery Exists Among Us

- The slaves of our times are not all those factory and workshop hands only who must sell themselves completely into the power of the factory and foundry-owners in order to exist, but nearly all the agricultural laborers are slaves, working, as they do, unceasingly to grow another's corn on another's field, and gathering it into another's barn; or tilling their own fields only in order to pay to bankers the interest on debts they cannot get rid of. And slaves also are all the innumerable footmen, cooks, porters, housemaids, coachmen, bathmen, waiters, etc., who all their life long perform duties most unnatural to a human being, and which they themselves dislike.

- Chapter 8: Slavery Exists Among Us

Slavery exists in full vigor, but we do not perceive it, just as in Europe at the end of the Eighteenth Century the slavery of serfdom was not perceived.

People of that day thought that the position of men obliged to till the land for their lords, and to obey them, was a natural, inevitable, economic condition of life, and they did not call it slavery.

It is the same among us: people of our day consider the position of the laborer to be a natural, inevitable economic condition, and they do not call it slavery. And as, at the end of the Eighteenth Century, the people of Europe began little by little to understand that what formerly seemed a natural and inevitable form of economic life-namely, the position of peasants who were completely in the power of their lords-was wrong, unjust and immoral, and demanded alteration, so now people today are beginning to understand that the position of hired workmen, and of the working classes in general, which formerly seemed quite right and quite normal, is not what it should be, and demands alteration.

- Chapter 8: Slavery Exists Among Us

The First Step (1892)

[edit]

- Translated by Aylmer Maude. Full text online at the Internet Archive.

- To be good and lead a good life means to give to others more than one takes from them.

- Ch. VII

- There is a scale of virtues, and it is necessary, if one would mount the higher steps, to begin with the lowest; and the first virtue a man must acquire if he wishes to acquire the others, is that which the ancients called ἐγκράτεια or σωφροσύνη — i.e., self-control or moderation.

- Ch. VIII

- I had wished to visit a slaughter-house, in order to see with my own eyes the reality of the question raised when vegetarianism is discussed. But at first I felt ashamed to do so, as one is always ashamed of going to look at suffering which one knows is about to take place, but which one cannot avert; and so I kept putting off my visit. But a little while ago I met on the road a butcher ... He is not yet an experienced butcher, and his duty is to stab with a knife. I asked him whether he did not feel sorry for the animals that he killed. He gave me the usual answer: 'Why should I feel sorry? It is necessary.' But when I told him that eating flesh is not necessary, but is only a luxury, he agreed; and then he admitted that he was sorry for the animals.

- Ch. IX

- Once ... I was offered a lift by some carters ... It was the Thursday before Easter. I was seated in the first cart, with a strong, red, coarse carman, who evidently drank. On entering a village we saw a well-fed, naked, pink pig being dragged out of the first yard to be slaughtered. It squealed in a dreadful voice, resembling the shriek of a man. Just as we were passing they began to kill it. A man gashed its throat with a knife. The pig squealed still more loudly and piercingly, broke away from the men, and ran off covered with blood. Being near-sighted I did not see all the details. I saw only the human-looking pink body of the pig and heard its desperate squeal; but the carter saw all the details and watched closely. They caught the pig, knocked it down, and finished cutting: its throat. When its squeals ceased the carter sighed heavily. 'Do men really not have to answer for such things?' he said.

- Ch. IX

- And see, a kind, refined lady will devour the carcasses of these animals with full assurance that she is doing right, at the same time asserting two contradictory propositions: First, that she is, as her doctor assures her, so delicate that she cannot be sustained by vegetable food alone, and that for her feeble organism flesh is indispensable; and, secondly, that she is so sensitive that she is unable, not only herself to inflict suffering on animals, but even to bear the sight of suffering. Whereas the poor lady is weak precisely because she has been taught to live upon food unnatural to man; and she cannot avoid causing suffering to animals — for she eats them.

- Ch. IX

- We are not ostriches, and cannot believe that if we refuse to look at what we do not wish to see, it will not exist. This is especially the case when what we do not wish to see is what we wish to eat. If it were really indispensable, or, if not indispensable, at least in some way useful! But it is quite unnecessary ... And this is continually being confirmed by the fact that young, kind, undepraved people — especially women and girls — without knowing how it logically follows, feel that virtue is incompatible with beefsteaks, and, as soon as they wish to be good, give up eating flesh.

- Ch. X

- The precise reason why abstinence from animal food will be the first act ... of a moral life is admirably explained in the book, The Ethics of Diet [by Howard Williams]; and not by one man only, but by all mankind in the persons of its best representatives during all the conscious life of humanity. ... the moral progress of humanity — which is the foundation of every other kind of progress — is always slow; but ... the sign of true, not casual, progress is its uninterruptedness and its continual acceleration. And the progress of vegetarianism is of this kind. That progress, is expressed both in the words of the writers cited in the above-mentioned book and in the actual life of mankind, which from many causes is involuntarily passing metre and more from carnivorous habits to vegetable food, and is also deliberately following the same path in a movement which shows evident strength, and which is growing larger and larger — viz., vegetarianism.

- Ch. X

The Kingdom of God is Within You (1894)

[edit]

- full text online: Or, Christianity Not As A Mystical Religion But As A New Theory Of Life. Translated from the Russian of Count Leo Tolstoy by Constance Garnett. New York: The Cassell Publishing Co. 31 East 17th St. (Union Square)

- In the year 1884 I wrote a book under the title "What I Believe," in which I did in fact make a sincere statement of my beliefs. In affirming my belief in Christ's teaching, I could not help explaining why I do not believe, and consider as mistaken, the Church's doctrine... Among the many points in which this doctrine falls short of the doctrine of Christ I pointed out as the principal one the absence of any commandment of non-resistance to evil by force. The perversion of Christ's teaching by the teaching of the Church is more clearly apparent in this than in any other point of difference.

- I know—as we all do—very little of the practice and the spoken and written doctrine of former times on the subject of non-resistance to evil. I knew what had been said on the subject by the fathers of the Church—Origen, Tertullian, and others—I knew too of the existence of some so-called sects of Mennonites, Herrnhuters, and Quakers, who do not allow a Christian the use of weapons, and do not enter military service; but I knew little of what had been done by these so-called sects toward expounding the question.

- The Quakers sent me books, from which I learnt how they had, years ago, established beyond doubt the duty for a Christian of fulfilling the command of non-resistance to evil by force, and had exposed the error of the Church's teaching in allowing war and capital punishment.

- Chapter I, The Doctrine of Non-resistance to Evil by Force has been Professed by a Minority of Men from the Very Foundation of Christianity

- Further acquaintance with the labors of the Quakers and their works — with Fox, Penn, and especially the work of Dymond (published in 1827) — showed me not only that the impossibility of reconciling Christianity with force and war had been recognized long, long ago, but that this irreconcilability had been long ago proved so clearly and so indubitably that one could only wonder how this impossible reconciliation of Christian teaching with the use of force, which has been, and is still, preached in the churches, could have been maintained in spite of it.

- Chapter I, The Doctrine of Non-resistance to Evil by Force has been Professed by a Minority of Men from the Very Foundation of Christianity

- William Lloyd Garrison took part in a discussion on the means of suppressing war in the Society for the Establishment of Peace among Men, which existed in 1838 in America. He came to the conclusion that the establishment of universal peace can only be founded on the open profession of the doctrine of non-resistance to evil by violence (Matt. v. 39), in its full significance, as understood by the Quakers, with whom Garrison happened to be on friendly relations. Having come to this conclusion, Garrison thereupon composed and laid before the society a declaration, which was signed at the time — in 1838 — by many members.

- Chapter I, The Doctrine of Non-resistance to Evil by Force has been Professed by a Minority of Men from the Very Foundation of Christianity

- The work of Garrison, the father, in his foundation of the Society of Non-resistants and his Declaration, even more than my correspondence with the Quakers, convinced me of the fact that the departure of the ruling form of Christianity from the law of Christ on non-resistance by force is an error that has long been observed and pointed out, and that men have labored, and are still laboring, to correct. Ballou's work confirmed me still more in this view. But the fate of Garrison, still more that of Ballou, in being completely unrecognized in spite of fifty years of obstinate and persistent work in the same direction, confirmed me in the idea that there exists a kind of tacit but steadfast conspiracy of silence about all such efforts.

- Chapter I, The Doctrine of Non-resistance to Evil by Force has been Professed by a Minority of Men from the Very Foundation of Christianity

- "Historically, Helchitsky attributes the degeneration of Christianity to the times of Constantine the Great, whom the Pope Sylvester admitted into the Christian Church with all his heathen morals and life. Constantine, in his turn, endowed the Pope with worldly riches and power. From that time forward these two ruling powers were constantly aiding one another to strive for nothing but outward glory. Divines and ecclesiastical dignitaries began to concern themselves only about subduing the whole world to their authority, incited men against one another to murder and plunder, and in creed and life reduced Christianity to a nullity. Helchitsky denies completely the right to make war and to inflict the punishment of death; every soldier, even the 'knight,' is only a violent evil doer—a murderer."

- Chapter I, The Doctrine of Non-resistance to Evil by Force has been Professed by a Minority of Men from the Very Foundation of Christianity

- The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.

- Chapter III, Christianity Misunderstood by Believers

- The Churches as Churches have always been and cannot fail to be institutions not only alien to, but directly hostile towards, Christ's teaching.

- Chapter III, Christianity Misunderstood by Believers

- The Churches as Churches—as institutions affirming their own infallibility—are anti-Christian institutions. Between the Churches as such and Christianity, not only is there nothing in common except the name, but they are two quite opposite and opposing principles. The one represents pride, violence, self-assertion, immobility and death: the other humility, penitence, meekness, progress, and life.

- Chapter III, Christianity Misunderstood by Believers

- The savage recognizes life only in himself and his personal desires. His interest in life is concentrated on himself alone. The highest happiness for him is the fullest satisfaction of his desires. The motive power of his life is personal enjoyment. His religion consists in propitiating his deity and in worshiping his gods, whom he imagines as persons living only for their personal aims.

- Chapter IV, Christianity Misunderstood by Men of Science

- The civilized pagan recognizes life not in himself alone, but in societies of men—in the tribe, the clan, the family, the kingdom —and sacrifices his personal good for these societies. The motive power of his life is glory. His religion consists in the exaltation of the glory of those who are allied to him—the founders of his family, his ancestors, his rulers—and in worshiping gods who are exclusively protectors of his clan, his family, his nation, his government

- Chapter IV, Christianity Misunderstood by Men of Science

- The man who holds the divine theory of life recognizes life not in his own individuality, and not in societies of individualities (in the family, the clan, the nation, the tribe, or the government), but in the eternal undying source of life—in God; and to fulfill the will of God he is ready to sacrifice his individual and family and social welfare. The motor power of his life is love. And his religion is the worship in deed and in truth of the principle of the whole—God.

- Chapter IV, Christianity Misunderstood by Men of Science

- The whole historic existence of mankind is nothing else than the gradual transition from the personal, animal conception of life to the social conception of life, and from the social conception of life to the divine conception of life.

- Chapter IV, Christianity Misunderstood by Men of Science

- We are all brothers—and yet every morning a brother or a sister must empty the bedroom slops for me. We are all brothers, but every morning I must have a cigar, a sweetmeat, an ice, and such things, which my brothers and sisters have been wasting their health in manufacturing, and I enjoy these things and demand them...We are all brothers, but I live on a salary paid me for prosecuting, judging, and condemning the thief or the prostitute whose existence the whole tenor of my life tends to bring about, and who I know ought not to be punished but reformed. We are all brothers, but I live on the salary I gain by collecting taxes from needy laborers to be spent on the luxuries of the rich and idle. We are all brothers, but I take a stipend for preaching a false Christian religion, which I do not myself believe in, and which only serves to hinder men from understanding true Christianity. I take a stipend as priest or bishop for deceiving men in the matter of the greatest importance to them. We are all brothers, but I will not give the poor the benefit of my educational, medical, or literary labors except for money. We are all brothers, yet I take a salary for being ready to commit murder, for teaching men to murder, or making firearms, gunpowder, or fortifications.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- The whole life of the upper classes is a constant inconsistency. The more delicate a man's conscience is, the more painful this contradiction is to him.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- The attitude of the ruling classes to the laborers is that of a man who has felled his adversary to the earth and holds him down, not so much because he wants to hold him down, as because he knows that if he let him go, even for a second, he would himself be stabbed, for his adversary is infuriated and has a knife in his hand. And therefore, whether their conscience is tender or the reverse, our rich men cannot enjoy the wealth they have filched from the poor as the ancients did who believed in their right to it. Their whole life and all their enjoyments are embittered either by the stings of conscience or by terror.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- What! all of us, Christians, not only profess to love one another, but do actually live one common life; we whose social existence beats with one common pulse—we aid one another, learn from one another, draw ever closer to one another to our mutual happiness, and find in this closeness the whole meaning of life!—and to-morrow some crazy ruler will say some stupidity, and another will answer in the same spirit, and then I must go expose myself to being murdered, and murder men—who have done me no harm—and more than that, whom I love. And this is not a remote contingency, but the very thing we are all preparing for, which is not only probable, but an inevitable certainty.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- To recognize this clearly is enough to drive a man out of his senses or to make him shoot himself. And this is just what does happen, and especially often among military men. A man need only come to himself for an instant to be impelled inevitably to such an end.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- And this is the only explanation of the dreadful intensity with which men of modern times strive to stupefy themselves, with spirits, tobacco, opium, cards, reading newspapers, traveling, and all kinds of spectacles and amusements. These pursuits are followed up as an important, serious business. And indeed they are a serious business. If there were no external means of dulling their sensibilities, half of mankind would shoot themselves without delay, for to live in opposition to one's reason is the most intolerable condition. And that is the condition of all men of the present day. All men of the modern world exist in a state of continual and flagrant antagonism between their conscience and their way of life. This antagonism is apparent in economic as well as political life. But most striking of all is the contradiction between the Christian law of the brotherhood of men existing in the conscience and the necessity under which all men are placed by compulsory military service of being prepared for hatred and murder—of being at the same time a Christian and a gladiator.

- Chapter V, Contradiction Between our Life and our Christian Conscience

- The error arises from the learned jurists deceiving themselves and others, by asserting that government is not what it really is, one set of men banded together to oppress another set of men, but, as shown by science, is the representation of the citizens in their collective capacity.

- Chapter VI, Attitude of Men of the Present Day to War

- Variant translation: Government is an association of men who do violence to the rest of us.

- All state obligations are against the conscience of a Christian: the oath of allegiance, taxes, law proceedings and military service.

- Chapter VII, Significance of Compulsory Service

- Armies are necessary, before all things, for the defense of governments from their own oppressed and enslaved subjects.

- Chapter VII, Significance of Compulsory Service