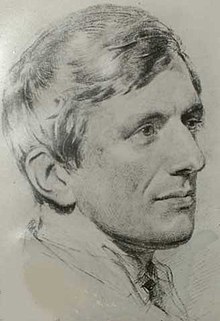

John Henry Newman

Appearance

(Redirected from John Henry Cardinal Newman)

Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English convert to Catholicism, later made a cardinal.

Quotes

[edit]1810s

[edit]- There is in stillness oft a magic power

To calm the breast, when struggling passions lower;

Touch'd by its influence, in the soul arise

Diviner feelings, kindred with the skies.- Solitude (1818)

1830s

[edit]- Men live after their death—they live not only in their writings or their chronicled history, but still more in that ἄγραφος μνήμη exhibited in a school of pupils who trace their moral parentage to them.

- Letter to Rev. S. Rickards (20 July 1830), quoted in Letters and Correspondence of John Henry Newman During His Life in the English Church With a Brief Autobiography, Vol. I, ed. Anne Mozley (1890), p. 203

- Time hath a taming hand.

- Persecution, st. 3 (1832)

- Sin can read sin, but dimly scans high grace.

- Isaac (1833)

- Christian! hence learn to do thy part,

And leave the rest to Heaven.- St. Paul at Melita, st. 3 (1833)

- Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home—

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet: I do not ask to see

The distant scene,—one step enough for me.- The Pillar of the Cloud, st. 1 (1833)

- And with the morn those angel faces smile

Which I have loved long since and lost awhile.- The Pillar of the Cloud, st. 3 (1833)

- There never was a time when God had not spoken to man, and told him to a certain extent his duty. His injunctions to Noah, the common father of all mankind, is the first recorded fact of the sacred history after the deluge. Accordingly, we are expressly told in the New Testament, that at no time He left Himself without witness in the world, and that in every nation He accepts those who fear and obey Him.

- The Arians of the Fourth Century, Their Doctrine, Temper, and Conduct, Chiefly as Exhibited in the Councils of the Church, Between A.D. 325, & A.D. 381 (1833), p. 88

- It would seem, then, that there is something true and divinely revealed, in every religion all over the earth, overloaded, as it may be, and at times even stifled by the impieties which the corrupt will and understanding of man have incorporated with it. Such are the doctrines of the power and presence of an invisible God, of His moral law and governance, of the obligation of duty, and the certainty of a just judgment, and of reward and punishment being dispensed in the end to individuals; so that revelation, properly speaking, is an universal, not a partial gift.

- The Arians of the Fourth Century, Their Doctrine, Temper, and Conduct, Chiefly as Exhibited in the Councils of the Church, Between A.D. 325, & A.D. 381 (1833), pp. 88-89

- The more I read of Athanasius, Theodoret, etc, the more I see that the ancients did make the Scriptures the basis of their belief. The only question is, would they have done so in another point besides the θεολογία (theology), etc, which happened in the early ages to be in discussion? I incline to say the Creed is the faith necessary to salvation, as well as to Church communion, and to maintain that Scripture, according to the Fathers, is the authentic record and document of this faith.

It surely is reasonable that 'necessary to salvation' should apply to the Baptismal Creed: 'In the name of,' etc (vid. He who believeth etc.). Now the Apostles' Creed is nothing but this; for the Holy Catholic Church, etc [in it] are but the medium through which God comes to us. Now this θεολογία, I say, the Fathers do certainly rest on Scripture, as upon two tables of stone. I am surprised more and more to see how entirely they fall into Hawkins’s theory even in set words, that Scripture proves and the Church teaches.[1]

I believe it would be extremely difficult to show that tradition is ever considered by them (in matters of faith) more than interpretative of Scripture. It seems that when a heresy rose they said at once ‘That is not according to the Church's teaching,’ i.e. they decided it by the praejudicium [N.B. prescription] of authority.

Again, when they met together in council, they brought the witness of tradition as a matter of fact, but when they discussed the matter in council, cleared their views, etc., proved their power, they always went to Scripture alone. They never said 'It must be so and so, because St. Cyrian says this, St. Clement explains in his third book of the "Paedagogue," etc.' and with reason; for the Fathers are a witness only as one voice, not in individual instances, or, much less, isolated passages, but every word of Scripture is inspired and available.- Letter to Richard Hurrell Froude (23 August 1835), quoted in Letters and Correspondence of John Henry Newman During His Life in the English Church, 1890, Anne Mozley, ed., Longmans’s Green & Co., London, New York, Volume 2, p. 113. [2]

- Surely, there is at this day a confederacy of evil, marshalling its hosts from all parts of the world, organizing itself, taking its measures, enclosing the Church of CHRIST as in a net, and preparing the way for a general apostasy from it. Whether this very apostasy is to give birth to Antichrist, or whether he is still to be delayed, we cannot know; but at any rate this apostasy, and all its tokens, and instruments, are of the Evil One and savour of death. Far be it from any of us to be of those simple ones, who are taken in that snare which is circling around us! Far be it from us to be seduced with the fair promises in which Satan is sure to hide his poison! Do you think he is so unskilful in his craft, as to ask you openly and plainly to join him in his warfare against the Truth? No; he offers you baits to tempt you. He promises you civil liberty; he promises you equality; he promises you trade and wealth; he promises you a remission of taxes; he promises you reform. This is the way in which he conceals from you the kind of work to which he is putting you; he tempts you to rail against your rulers and superiors; he does so himself, and induces you to imitate him; or he promises you illumination, he offers you knowledge, science, philosophy, enlargement of mind. He scoffs at times gone by; he scoffs at every institution which reveres them. He prompts you what to say, and then listens to you, and praises you, and encourages you. He bids you mount aloft. He shows you how to become as gods. Then he laughs and jokes with you, and gets intimate with you; he takes your hand, and gets his fingers between yours, and grasps them, and then you are his.

- Tract 83 (29 June 1838)

Parochial and Plain Sermons (1834–1842)

[edit]- Parochial and Plain Sermons (London: Rivingtons, 1868), 8 vol. The first six volumes are reprinted from the six volumes of Parochial Sermons (1834–1842); the seventh and eighth formed the fifth volume of Plain Sermons, by Contributors to Tracts for the Times (1843), which was Newman's contribution to the series.

- Do not think I am speaking of one or two men, when I speak of the scandal which a Christian's inconsistency brings upon his cause. The Christian world, so called, what is it practically, but a witness for Satan rather than a witness for Christ? Rightly understood, doubtless the very disobedience of Christians witnesses for Him who will overcome whenever He is judged. But is there any antecedent prejudice against religion so great as that which is occasioned by the lives of its professors? Let us ever remember, that all who follow God with but a half heart, strengthen the hands of His enemies, give cause of exultation to wicked men, perplex inquirers after truth, and bring reproach upon their Saviour's name.

- Vol. 1, Sermon 10: Profession without Practice, p. 136

- If Christ has constituted one Holy Society (which He has done); if His Apostles have set it in order (which they did), and have expressly bidden us (as they have in Scripture) not to undo what they have begun; and if (in matter of fact) their work so set in order and so blessed is among us to this day (as it is), and we partakers of it, it were a traitor's act in us to abandon it, an unthankful slight on those who have preserved it for so many ages, a cruel disregard of those who are to come after us, nay of those now alive who are external to it and might otherwise be brought into it. We must transmit as we have received. We did not make the Church, we may not unmake it.

- Vol. 3, Sermon 14: Submission to Church Authority, p. 202

- The Apostles lived eighteen hundred years since; and as far as the Christian looks back, so far can he afford to look forward. There is one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, from first to last.

- Vol. 3, Sermon 17: The Visible Church an Encouragement to Faith, p. 250

- Reason is God's gift; but so are the passions.

- Vol. 5, Sermon 8: The State of Innocence, p. 114

- Now what is it that moves our very hearts and sickens us so much at cruelty shown to poor brutes? I suppose this first, that they have done no harm; next that they have no power whatever of resistance; it is the cowardice and tyranny of which they are the victims which makes their sufferings so especially touching. For instance, if they were dangerous animals, take the case of wild beasts at large, able not only to defend themselves, but even to attack us; much as we might dislike to hear of their wounds and agony, yet our feelings would be of a very different kind; but there is something so very dreadful, so satanic, in tormenting those who never have harmed us, who cannot defend themselves, who are utterly in our power, who have weapons neither of offence nor defence, that none but very hardened persons can endure the thought of it.

- Vol. 7, Sermon 10: The Crucifixion, p. 137

- Part of this text is widely quoted with the addition of the sentence, "Cruelty to animals is as if man did not love God", which is not present in the sermon.

- Again, are not the principles of unbelief certain to dissolve human society? and is not this plain fact, candidly considered, enough to show that unbelief cannot be a right condition of our nature? for who can believe that we were intended to live in anarchy? If we have no good reasons for believing, at least we have no good reasons for disbelieving. If you ask why we are Christians, we ask in turn, why should we not be Christians? It will be enough to remain where we are, till you do what you never can do—prove to us for certain that the Gospel is not Divine.

- Vol. 8, Sermon 8: Inward Witness to the Gospel, p. 112

1840s

[edit]- We can believe what we choose. We are answerable for what we choose to believe.

- Letter to Mrs William Froude (27 June 1848)

- O my brethren, turn away from the Catholic Church, and to whom will you go? it is your only chance of peace and assurance in this turbulent, changing world. There is nothing between it and scepticism, when men exert their reason freely. Private creeds, fancy religions, may be showy and imposing to the many in their day; national religions may lie huge and lifeless, and cumber the ground for centuries, and distract the attention or confuse the judgment of the learned; but on the long run it will be found that either the Catholic Religion is verily and indeed the coming in of the unseen world into this, or that there is nothing positive, nothing dogmatic, nothing real in any of our notions as to whence we come and whither we are going. Unlearn Catholicism, and you become Protestant, Unitarian, Deist, Pantheist, sceptic, in a dreadful, but infallible succession.

- Discourses Addressed to Mixed Congregations (1849), p. 298

Sermons Bearing on Subjects of the Day (1843)

[edit]- Sermons Bearing on Subjects of the Day (London: J. G. F. & G. Rivington, 1843)

- Such is the rule of our warfare. We advance by yielding; we rise by falling; we conquer by suffering; we persuade by silence; we become rich by bountifulness; we inherit the earth through meekness; we gain comfort through mourning; we earn glory by penitence and prayer. Heaven and earth shall sooner fall than this rule be reversed; it is the law of Christ's kingdom, and nothing can reverse it but sin.

- Sermon XII: Joshua a Type of Christ and His followers, p. 184

- [W]hether we will believe it or no, the truth remains, that the strength of the Church, as heretofore, does not lie in earthly law, or human countenance, or civil station, but in her proper gifts; in those great gifts which our Lord pronounced to be beatitudes. Blessed are the poor in spirit, the mourners, the meek, the thirsters after righteousness, the merciful, the pure in heart, the peace makers, the persecuted.

- Sermon XVIII: Condition of the Members of the Christian Empire, pp. 308-309

- May He support us all the day long, till the shades lengthen, and the evening comes, and the busy world is hushed, and the fever of life is over, and our work is done! Then in His mercy may He give us safe lodging, and a holy rest, and peace at the last!

- Sermon XX: Wisdom and Innocence, p. 347

- O my brethren, O kind and affectionate hearts, O loving friends, should you know any one whose lot it has been, by writing or by word of mouth, in some degree to help you thus to act; if he has ever told you what you knew about yourselves, or what you did not know; has read to you your wants or feelings, and comforted you by the very reading; has made you feel that there was a higher life than this daily one, and a brighter world than that you see; or encouraged you, or sobered you, or opened a way to the inquiring, or soothed the perplexed; if what he has said or done has ever made you take interest in him, and feel well inclined towards him; remember such a one in time to come, though you hear him not, and pray for him, that in all things he may know God's will, and at all times he may be ready to fulfil it.

- Sermon XXVI: The Parting of Friends (sermon preached on Monday, 25 September, 1843), pp. 463–464

An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845)

[edit]

- Whatever be historical Christianity, it is not Protestantism. If ever there were a safe truth, it is this.

- Introduction, p. 5

- In a higher world it is otherwise; but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.

- Chapter 1, Section 1, p. 39

- We are told that God has spoken. Where? In a book? We have tried it, and it disappoints; it disappoints, that most holy and blessed gift, not from fault of its own, but because it is used for a purpose for which it was not given. The Ethiopian's reply, when St. Philip asked him if he understood what he was reading, is the voice of nature; "How can I, unless some man shall guide me?" The Church undertakes that office; she does what none else can do, and this is the secret of the power.

- Chapter 2, Section 2, Part 7, p. 126

1850s

[edit]- Where good and ill together blent,

Wage an undying strife.- A Martyr Convert, st. 3 (1856). Also in Callista Chapter 36 (1855)

Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England (1851)

[edit]- Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England: Addressed to the Brothers of the Oratory (London: Burns & Lambert, 1851)

- After he had gone over the mansion, his entertainer asked him what he thought of the splendours it contained; and he in reply did full justice to the riches of its owner and the skill of its decorators, but he added, "Lions would have fared better, had lions been the artists."

- Lecture I, p. 4.

- I want a laity, not arrogant, not rash in speech, not disputatious, but men who know their religion, who enter into it, who know just where they stand, who know what they hold and what they do not, who know their creed so well, that they can give an account of it, and who know enough of history to defend it. I want an intelligent, well-instructed laity.

- Lecture IX, pp. 372–373

- Nothing would be done at all, if a man waited till he could do it so well, that no one could find fault with it.

- Lecture IX, p. 385

1860s

[edit]- It is then an integral portion of the Faith fixed by Ecumenical Council, a portion of it which you hold as well as I, that the Blessed Virgin is Theotocos, Deipara, or Mother of God; and this word, when thus used, carries with it no admixture of rhetoric, no taint of extravagant affection,—it has nothing else but a well-weighed, grave, dogmatic sense, which corresponds and is adequate to its sound. It intends to express that God is her Son, as truly as any one of us is the son of his own mother.

- A Letter to the Rev. E. B. Pusey, D.D. On His Recent Eirenicon (1866), p. 66

- So living Nature, not dull Art,

Shall plan my ways and rule my heart.- Nature and Art, st. 12 (1868)

Apologia Pro Vita Sua [A defense of one's own life] (1864)

[edit]- Apologia Pro Vita Sua (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1890)

- Growth is the only evidence of life.

- Ch. I, p. 5

- I do not shrink from uttering my firm conviction that it would be a gain to the country were it vastly more superstitious, more bigoted, more gloomy, more fierce in its religion than at present it shows itself to be.

- Ch. II, p. 46

- From the age of fifteen, dogma has been the fundamental principle of my religion: I know no other religion; I cannot enter into the idea of any other sort of religion; religion, as a mere sentiment, is to me a dream and a mockery.

- Ch. II, p. 49

- As I have already said, there are but two alternatives, the way to Rome, and the way to Atheism.

- Ch. IV, p. 204

- Ten thousand difficulties do not make one doubt.

- Ch. V, p. 239

- The Catholic Church claims, not only to judge infallibly on religious questions, but to animadvert on opinions in secular matters which bear upon religion, on matters of philosophy, of science, of literature, of history, and it demands our submission to her claim. It claims to censure books, to silence authors, and to forbid discussions. In all this it does not so much speak doctrinally, as enforce measures of discipline. It must of course be obeyed without a word, and perhaps in process of time it will tacitly recede from its own injunctions. In such cases the question of faith does not come in; for what is matter of faith is true for all times, and never can be unsaid.

- Ch. V, p. 257

- Moreover, there is this harm too, and one of vast extent, and touching men generally, that by insincerity and lying faith and truth are lost, which are the firmest bonds of human society, and, when they are lost, supreme confusion follows in life, so that men seem in nothing to differ from devils.

- Ch. V, p. 281

- Now by Liberalism I mean false liberty of thought, or the exercise of thought upon matters, in which, from the constitution of the human mind, thought cannot be brought to any successful issue, and therefore is out of place. Among such matters are first principles of whatever kind; and of these the most sacred and momentous are especially to be reckoned the truths of Revelation. Liberalism then is the mistake of subjecting to human judgment those revealed doctrines which are in their nature beyond and independent of it, and of claiming to determine on intrinsic grounds the truth and value of propositions which rest for their reception simply on the external authority of the Divine Word.

- Note A: Liberalism, p. 288. In Martin J. Svaglic edition (1967), pp. 255–56

The Dream of Gerontius (1865)

[edit]- Firmly I believe and truly

God is Three, and God is One;

And I next acknowledge duly

Manhood taken by the Son.- Part I, line 76

- It is thy very energy of thought

Which keeps thee from thy God.- Part III, line 45

- Praise to the Holiest in the height,

And in the depth be praise:

In all His words most wonderful;

Most sure in all His ways!- Part V, line 4

1870s

[edit]- I begin by assuming that the Church is in the world, and the world in the Church, and that the world, whether in the Church or not, totus in maligno positus est, that though it profess the Christian religion, though its millions are separately baptized, though its ranks and professions, though its governments, its great men, its laws, its science, its armies, accept the Gospel as the one rule of faith and practice, still mundus totus in maligno positus est. Moreover, that this is true in all ages and places—so that in all times, including the medieval multi sunt vocati, pauci electi, and the apostolic labour, like St. Paul, omnia sustinet propter electos.

- Letter to W. S. Lilly (25 July 1876), quoted in The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Volume XXVIII: Fellow of Trinity, January 1876 to December 1878, eds. Charles Stephen Dessain and Thomas Gornall, S.J. (1975), pp. 95-96

- The natural truths of science, physical, moral, social, political, material, are all from God—as those of the supernatural order are. Man abused supernatural truths in the medieval time, as well as used them; and now man uses natural truths, as well as abuses them. I am not determining which of the two abuses is the greater profanation, I only say that the one age is not all light, the other all darkness; and I think that, in matter of fact, more can be said for this age than you seem to allow.

- Letter to W. S. Lilly (25 July 1876), quoted in The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Volume XXVIII: Fellow of Trinity, January 1876 to December 1878, eds. Charles Stephen Dessain and Thomas Gornall, S.J. (1975), p. 96

Essays Critical and Historical (1871)

[edit]- Essays Critical and Historical (London: Basil Montagu Pickering, 1871)

- Now it is very intelligible to deny that there is any divinely established, divinely commissioned, Church at all; but to hold that the one Church is realized nd perfected in each of a thousand independent corporate units, co-ordinate, bound by no necessary intercommunion, adjusted into no divinely organized whole, is a tenet, not merely unknown to Scripture, but so plainly impossible to carry out practically, as to make it clear that it never would have been devised, except by men, who conscientiously believing in a visible Church and also conscientiously opposed to Rome, had nothing left for them, whether they would or would not, but to entrench themselves in the paradox, that the Church was one indeed, and the Church was Catholic indeed, but that he one Church was not the Catholic, and the Catholic Church was not the one.

- Vol. II, Note on Essay IX, p. 91.

- There is this obvious, undeniable difficulty in the attempt to form a theory of Private Judgment, in the choice of a religion, that Private Judgment leads different minds in such different directions. If, indeed, there be no religious truth, or at least no sufficient means of arriving at it, then the difficulty vanishes: for where there is nothing to find, there can be no rules for seeking, and contradiction in the result is but a reductio ad absurdum of the attempt.

- Vol. II, Essay XIII: "Private Judgment", p. 336. First published in British Critic (July 1841).

- Flagrant evils cure themselves by being flagrant.

- Vol. II, Essay XIII: "Private Judgment", p. 365.

The Idea of a University (1873)

[edit]- There is a knowledge which is desirable, though nothing come of it, as being of itself a treasure, and a sufficient remuneration of years of labor.

- Discourse V, pt. 6

- Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another.

- Discourse V, pt. 9.

- Liberal Education makes not the Christian, not the Catholic, but the gentleman. It is well to be a gentlemen, it is well to have a cultivated intellect, a delicate taste, a candid, equitable, dispassionate mind, a noble and courteous bearing in the conduct of life. These are the connatural qualities of a large knowledge; they are the objects of a University; I am advocating, I shall illustrate and insist upon them; but still, I repeat, they are no guarantee for sanctity or even for conscientiousness, they may attach to the man of the world, to the profligate, to the heartless,—pleasant, alas, and attractive as he shows when decked out in them.

- Discourse V, pt. 9.

- The world is content with setting right the surface of things.

- Discourse VIII, pt. 8.

- It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain.

- A great memory does not make a philosopher, any more than a dictionary can be called grammar.

- Discourse VIII, pt. 10.

A Letter Addressed to His Grace the Duke of Norfolk (1875)

[edit]- A Letter Addressed to His Grace the Duke of Norfolk on Occasion of Mr. Gladstone's Recent Expostulation (London: B M Pickering, 1875)

- We must either give up the belief in the Church as a divine institution altogether, or we must recognize it in that communion of which the Pope is the head. With him alone and round about him are found the claims, the prerogatives, and duties which we identify with the kingdom set up by Christ. We must take things as they are; to believe in a Church, is to believe in the Pope. And thus this belief in the Pope and his attributes, which seems so monstrous to Protestants, is bound up with our being Catholics at all; as our Catholicism is with our Christianity.

- Part III: The Papal Church, p. 27

- [T]he course of ages has fulfilled the prophecy and promise, "Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build My Church; and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth, shall be bound in heaven, and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven." That which in substance was possessed by the Nicene Hierarchy, that the Pope claims now.

- Part III: The Papal Church, p. 27

- Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ, a prophet in its informations, a monarch in its peremptoriness, a priest in its blessings and anathemas, and, even though the eternal priesthood throughout the Church could cease to be, in it the sacerdotal principle would remain and would have a sway.

- Part V: Conscience, p. 57

- When men advocate the rights of conscience, they in no sense mean the rights of the Creator, nor the duty to Him, in thought and deed, of the creature; but the right of thinking, speaking, writing, and acting, according to their judgment or their humour, without any thought of God at all. They do not even pretend to go by any moral rule, but they demand, what they think is an Englishman's prerogative, to be his own master in all things, and to profess what he pleases, asking no one's leave, and accounting priest or preacher, speaker or writer, unutterably impertinent, who dares to say a word against his going to perdition, if he like it, in his own way. Conscience has rights because it has duties; but in this age, with a large portion of the public, it is the very right and freedom of conscience to dispense with conscience, to ignore a Lawgiver and Judge, to be independent of unseen obligations. It becomes a license to take up any or no religion, to take up this or that and let it go again, to go to Church, to go to chapel, to boast of being above all religions and to be an impartial critic of each of them. Conscience is a stern monitor, but in this century it has been superseded by a counterfeit, which the eighteen centuries prior to it never heard of, and could not have mistaken for it, if they had. It is the right of self-will.

- Part V: Conscience, p. 58

- Certainly, if I am obliged to bring religion into after-dinner toasts, (which indeed does not seem quite the thing) I shall drink,—to the Pope, if you please,—still, to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.

- Part V: Conscience, p. 66

Speech of His Eminence Cardinal Newman on the Reception of the "Biglietto" at Cardinal Howard's Palace in Rome (12 May 1879)

[edit]- Speech of His Eminence Cardinal Newman on the Reception of the "Biglietto" at Cardinal Howard's Palace in Rome on the 12th of May 1879. With the Address of the English-Speaking Catholics in Rome and His Eminence's Reply to it, at the English College on the 14th of May 1879 (1879).

- For 30, 40, 50 years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion... Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another, and this is the teaching which is gaining substance and force daily. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion, as true.

- pp. 6-7

- Hitherto the civil Power has been Christian. Even in countries separated from the Church, as in my own, the dictum was in force, when I was young, that: "Christianity was the law of the land". Now, every where that goodly framework of society which is the creation of Christianity is throwing off Christianity. The dictum to which I have referred, with a hundred others which followed upon it, is gone, or is going every where; and, by the end of the century, unless the Almighty interferes, it will be forgotten. Hitherto, it has been considered that Religion alone, with its supernatural sanctions, was strong enough to secure submission of the masses of our population to law and order; now the Philosophers and Politicians are bent on satisfying this problem without the aid of Christianity.

- pp. 7-8

- [T]here is much in the liberalistic theory which is good and true; for example, not to say more, the precepts of justice, truthfulness, sobriety, self-command, benevolence, which, as I have already noted are among its avowed principles, and the natural laws of society. It is not till we find that this array of principles is intended to supersede, to block out, religion, that we pronounce it to be evil. There never was a device of the Enemy, so cleverly framed, and with such promise of success.

- pp. 9-10

1880s

[edit]- Nor does it matter, whether one or two Isaiahs wrote the book which bears that Prophet's name; the Church, without settling this point, pronounces it inspired in respect of faith and morals, both Isaiahs being inspired; and, if this be assured to us, all other questions are irrelevant and unnecessary.

- 'On the Inspiration of Scripture', The Nineteenth Century, No. 84 (February 1884), p. 196

- From what has been last said it follows, that the titles of the Canonical books, and their ascription to definite authors, either do not come under their inspiration, or need not be accepted literally.

- 'On the Inspiration of Scripture', The Nineteenth Century, No. 84 (February 1884), p. 196

- Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem!

- Translation: From shadows and symbols into the truth!

- His own epitaph at Edgbaston

Quotes about Newman

[edit]- At dinner we talked of Newman, whose Dream of Gerontius Gladstone puts very high, so high that he speaks of it in the same breath with the Divina Commedia. At length he asked, "Which of his writings will be read in a hundred years?" "Well," said Henry Smith, "certainly his hymn, 'Lead kindly Light,' and 'The Parting of Friends,' the sermon he preached before leaving Littlemore." "I go further," said Gladstone. "I think all his parochial sermons will be read."

- Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff, in Notes from a Diary, 1851-1901: 1873-1881 (1898), p. 140.

- [His earlier poems are] unequalled for grandeur of outline, purity of taste and radiance of total effect.

- R.H. Hutton; cited in: Hugh Chisholm. The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, Volume 19, (1911), p. 519

External links

[edit]- Newman Reader Works of John Henry Newman broken link (HTTP Error 503. The service is unavailable.) not accessed 2-23-13)

Categories:

- 1801 births

- 1890 deaths

- Anti-communists

- Beatified people

- Cardinals

- Catholics from England

- Clergy from the United Kingdom

- Conservatives from the United Kingdom

- Critics from the United Kingdom

- Humanists

- Hymnwriters from England

- Novelists from England

- People from London

- Philosophers from England

- Poets from England

- Roman Catholic bishops

- Theologians from England

- Victorian novelists