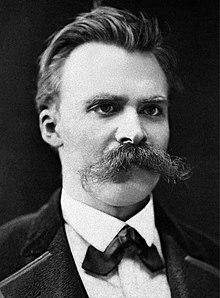

Friedrich Nietzsche

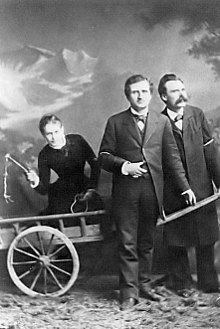

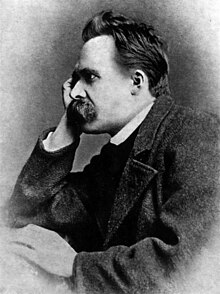

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, cultural critic, composer, poet, writer, and philologist whose work has exerted a profound influence on modern intellectual history. His critiques of contemporary culture, religion, and philosophy centered on a basic question regarding the foundation of values and morality.

- See also:

Human, All Too Human

The Dawn (book)

Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Beyond Good and Evil

Twilight of the Idols

Ecce Homo (book)

The Antichrist

Quotes

[edit]

- I am utterly amazed, utterly enchanted! I have a precursor, and what a precursor! I hardly knew Spinoza: that I should have turned to him just now, was inspired by "instinct." Not only is his overtendency like mine—namely to make all knowledge the most powerful affect — but in five main points of his doctrine I recognize myself; this most unusual and loneliest thinker is closest to me precisely in these matters: he denies the freedom of the will, teleology, the moral world-order, the unegoistic, and evil. Even though the divergencies are admittedly tremendous, they are due more to the difference in time, culture, and science. In summa: my lonesomeness, which, as on very high mountains, often made it hard for me to breathe and make my blood rush out, is now at least a twosomeness. Strange! Incidentally, I am not at all as well as I had hoped. Exceptional weather here too! Eternal change of atmospheric conditions! — that will yet drive me out of Europe! I must have clear skies for months, else I get nowhere. Already six severe attacks of two or three days each. With affectionate love, Your friend.

- Postcard to Franz Overbeck, Sils-Maria (30 July 1881), as translated by Walter Kaufmann in The Portable Nietzsche (1954)

- Here the ways of men part: if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire.

- Letter to Elisabeth Nietzsche, Bonn, 1865-06-11[specific citation needed]. Quoted in Walter Kaufmann, The Faith of a Heretic (opening epigram).

- Against that positivism which stops before phenomena, saying "there are only facts," I should say: no, it is precisely facts that do not exist, only interpretations...[1]

- Notebooks (Late 1886 – Spring 1887)

- Popular usage: There are no facts, only interpretations.

- In Germany there is much complaining about my "eccentricities." But since it is not known where my center is, it won't be easy to find out where or when I have thus far been "eccentric." That I was a philologist, for example, meant that I was outside my center (which fortunately does not mean that I was a poor philologist). Likewise, I now regard my having been a Wagnerian as eccentric. It was a highly dangerous experiment; now that I know it did not ruin me, I also know what significance it had for me — it was the most severe test of my character.

- Letter to Carl Fuchs (14 December 1887)

- I now myself live, in every detail, striving for wisdom, while I formerly merely worshipped and idolized the wise.

- Letter to Mathilde Mayer, July 16, 1878, cited in Karl Jaspers, Nietzsche (Baltimore: 1997), p. 46

- So far no one had had enough courage and intelligence to reveal me to my dear Germans. My problems are new, my psychological horizon frighteningly comprehensive, my language bold and clear; there may well be no books written in German which are richer in ideas and more independent than mine.

- Letter to Carl Fuchs (14 December 1887)

- I've seen proof, black on white, that Herr Dr. Förster has not yet severed his connection with the anti-Semitic movement. ... Since then I've had difficulty coming up with any of the tenderness and protectiveness I've so long felt toward you. The separation between us is thereby decided in really the most absurd way. Have you grasped nothing of the reason why I am in the world? ... Now it has gone so far that I have to defend myself hand and foot against people who confuse me with these anti-Semitic canaille; after my own sister, my former sister, and after Widemann more recently have given the impetus to this most dire of all confusions. After I read the name Zarathustra in the anti-Semitic Correspondence my forbearance came to an end. I am now in a position of emergency defense against your spouse's Party. These accursed anti-Semite deformities shall not sully my ideal!!

- Draft for a letter[dead link] to his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche (December 1887).[specific citation needed]

- You have committed one of the greatest stupidities — for yourself and for me! Your association with an anti-Semitic chief expresses a foreignness to my whole way of life which fills me again and again with ire or melancholy. ... It is a matter of honor with me to be absolutely clean and unequivocal in relation to anti-Semitism, namely, opposed to it, as I am in my writings. I have recently been persecuted with letters and Anti-Semitic Correspondence Sheets. My disgust with this party (which would like the benefit of my name only too well!) is as pronounced as possible, but the relation to Förster, as well as the aftereffects of my former publisher, the anti-Semitic Schmeitzner, always brings the adherents of this disagreeable party back to the idea that I must belong to them after all. ... It arouses mistrust against my character, as if publicly I condemned something which I have favored secretly — and that I am unable to do anything against it, that the name of Zarathustra is used in every Anti-Semitic Correspondence Sheet, has almost made me sick several times.

- Objecting to his sister Elisabeth, about her marriage to the anti-semite Bernhard Förster, in a Christmas letter (1887) in Friedrich Nietzsche's Collected Letters, Vol. V, #479

- Style ought to prove that one believes in an idea; not only that one thinks it but also feels it.

- Letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé (August 1882)

- Mathematics would certainly have not come into existence if one had known from the beginning that there was in nature no exactly straight line, no actual circle, no absolute magnitude.

- As quoted in The Puzzle Instinct : The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life (2004) by Marcel Danesi, p. 71 from Human All-Too-Human

- Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft, mag zusehn, dass er nicht dabei zum Ungeheuer wird. Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein.

- He who fights with monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.

- Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146

- Ist das Leben nicht hundert Mal zu kurz, sich in ihm— zu langweilen?

- Is not life a hundred times too short for us— to bore ourselves?

- Beyond Good and Evil, Chapter VII, 227

- Für jede hohe Welt muß man geboren sein; deutlicher gesagt, man muß für sie gezüchtet sein: ein Recht auf Philosophie -- das Wort im grossen Sinne genommen -- hat man nur Dank seiner Abkunft, die Vorfahren, das »Geblüt« entscheidet auch hier. Viele Geschlechter müssen der Entstehung des Philospohen vorgearbeitet haben; jede seiner Tungenden muß einzeln erworben, gepflegt, fortgeerbt, einverleibt worden sein...

- One must be born to any superior world — to make it plainer, one must be bred for it. One has a right to philosophy (taking the word in its greatest sense) only by virtue of one's breeding; one's ancestors, one's "blood," decides this, too. Many generations must have worked on the origin of a philosopher; each one of his virtues must have been separately earned, cared for, passed on, and embodied.

- Beyond Good and Evil, translated by Marianne Cowan [Henry Regnery Company, 1955, p. 139]; Jenseits von Gut und Böse [Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 1988, p. 130]

- wir vermeinen, daß Härte, Gewaltsamkeit, Sklaverie, Gefahr auf der Gasse und im Herzen, Verborgenheit, Stoicismus, Versucherkunst und Teufelei jeder Art, daß alles Böse, Furchtbare, Tyrannische, Raubthier- und Schlangenhafte am Menschen so gut zur Erhöhung der Species »Mensch« dient, als sein Gegensatz...

- We imagine that hardness, violence, slavery, peril in the street and in the heart, concealment, Stoicism, temptation, and deviltry of every sort, everything evil, frightful, tyrannical, raptor- and snake-like in man, serves as well for the advancement of the species "man" as their opposite.

- Beyond Good and Evil, translated by Marianne Cowan [Henry Regnery Company, 1955, p. 50]; Jenseits von Gut und Böse [Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 1988, p. 130]

- Man verdirbt einen Jüngling am sichersten, wenn man ihn anleitet, den Gleichdenkenden höher zu achten, als den Andersdenkenden.

- The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.

- The Dawn, Sec. 297

- Although the most acute judges of the witches and even the witches themselves, were convinced of the guilt of witchery, the guilt nevertheless was non-existent. It is thus with all guilt.

- As translated in The Portable Nietzsche (1954) by Walter Kaufmann, p. 96

- Freier Wille ohne Fatum ist ebenso wenig denkbar, wie Geist ohne Reelles, Gutes ohne Böses.

- Free will without fate is no more conceivable than spirit without matter, good without evil.

- "Fatum und Geschichte," April 1862

- Free will without fate is no more conceivable than spirit without matter, good without evil.

- Sobald es aber möglich wäre, durch einen starken Willen die ganze Weltvergangenheit umzustürzen, sofort träten wir in die Reihe der unabhängigen Götter, und Weltgeschichte hieße dann für uns nichts als ein träumerisches Selbstentrücktsein; der Vorhang fällt, und der Mensch findet sich wieder, wie ein Kind mit Welten spielend, wie ein Kind, das beim Morgenglühen aufwacht und sich lachend die furchtbaren Träume von der Stirn streicht.

- As soon as it becomes possible, by dint of a strong will, to overthrow the entire past of the world, then, in a single moment, we will join the ranks of independent gods. World history for us will then be nothing but a dreamlike otherworldly being. The curtain falls, and man once more finds himself a child playing with whole worlds—a child, awoken by the first glow of morning, who laughingly wipes the frightful dreams from his brow.

- "Fatum und Geschichte," April 1862

- As soon as it becomes possible, by dint of a strong will, to overthrow the entire past of the world, then, in a single moment, we will join the ranks of independent gods. World history for us will then be nothing but a dreamlike otherworldly being. The curtain falls, and man once more finds himself a child playing with whole worlds—a child, awoken by the first glow of morning, who laughingly wipes the frightful dreams from his brow.

- The modern scientific counterpart to belief in God is the belief in the universe as an organism: this disgusts me. This is to make what is quite rare and extremely derivative, the organic, which we perceive only on the surface of the earth, into something essential, universal, and eternal! This is still an anthropomorphizing of nature!

- KSA 9,11 [201]

- Is Wagner a human being at all? Is he not rather a disease? He contaminates everything he touches - he has made music sick.

- Der Fall Wagner (1888)

- May I really say it! All truths are bloody truths to me—take a look at my previous writings.

- Notebooks (Summer 1880) 4[271]

- This is the mistake which I seem to make eternally, that I imagine the sufferings of others as far greater than they really are. Ever since my childhood, the proposition ‘my greatest dangers lie in pity’ has been confirmed again and again.

- 1884 Letter

The Birth of Tragedy (1872)

[edit]- The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music (1873), later expanded as The Birth of Tragedy, Or: Hellenism and Pessimism (1886), Shaun Whiteside translation, Penguin Classics (1993)

- Nochmals gesagt, heute ist es mir ein unmögliches Buch, - ich heisse es schlecht geschrieben, schwerfällig, peinlich, bilderwüthig und bilderwirrig, gefühlsam, hier und da verzuckert bis zum Femininischen, ungleich im Tempo, ohne Willen zur logischen Sauberkeit, sehr überzeugt und deshalb des Beweisens sich überhebend, misstrauisch selbst gegen die Schicklichkeit des Beweisens, als Buch für Eingeweihte, als "Musik" für Solche, die auf Musik getauft, die auf gemeinsame und seltene Kunst-Erfahrungen hin von Anfang der Dinge an verbunden sind, als Erkennungszeichen für Blutsverwandte in artibus, - ein hochmüthiges und schwärmerisches Buch, das sich gegen das profanum vulgus der "Gebildeten" von vornherein noch mehr als gegen das "Volk" abschliesst, welches aber, wie seine Wirkung bewies und beweist, sich gut genug auch darauf verstehen muss, sich seine Mitschwärmer zu suchen und sie auf neue Schleichwege und Tanzplätze zu locken.

- To say it once again: today I find it an impossible book — badly written, clumsy and embarrassing, its images frenzied and confused, sentimental, in some places saccharine-sweet to the point of effeminacy, uneven in pace, lacking in any desire for logical purity, so sure of its convictions that it is above any need for proof, and even suspicious of the propriety of proof, a book for initiates, 'music' for those who have been baptized in the name of music and who are related from the first by their common and rare experiences of art, a shibboleth for first cousins in artibus [in the arts] an arrogant and fanatical book that wished from the start to exclude the profanum vulgus [the profane mass] of the 'educated' even more than the 'people'; but a book which, as its impact has shown and continues to show, has a strange knack of seeking out its fellow-revellers and enticing them on to new secret paths and dancing-places.

- "Attempt at a Self-Criticism", p. 5

- Oh wie ferne war mir damals gerade dieser ganze Resignationismus!

- How far I was then from all that resignationism!

- "Attempt at a Self-criticism", p. 10

- Diesen Ernsthaften diene zur Belehrung, dass ich von der Kunst als der höchsten Aufgabe und der eigentlich metaphysischen Thätigkeit dieses Lebens im Sinne des Mannes überzeugt bin, dem ich hier, als meinem erhabenen Vorkämpfer auf dieser Bahn, diese Schrift gewidmet haben will.

- Art is the supreme task and the truly metaphysical activity in this life...

- "Preface to Richard Wagner", p. 13

- Wie nun der Philosoph zur Wirklichkeit des Daseins, so verhält sich der künstlerisch erregbare Mensch zur Wirklichkeit des Traumes; er sieht genau und gern zu: denn aus diesen Bildern deutet er sich das Leben, an diesen Vorgängen übt er sich für das Leben. Nicht etwa nur die angenehmen und freundlichen Bilder sind es, die er mit jener Allverständigkeit an sich erfährt: auch das Ernste, Trübe, Traurige, Finstere, die plötzlichen Hemmungen, die Neckereien des Zufalls, die bänglichen Erwartungen, kurz die ganze "göttliche Komödie" des Lebens, mit dem Inferno, zieht an ihm vorbei, nicht nur wie ein Schattenspiel - denn er lebt und leidet mit in diesen Scenen - und doch auch nicht ohne jene flüchtige Empfindung des Scheins; und vielleicht erinnert sich Mancher, gleich mir, in den Gefährlichkeiten und Schrecken des Traumes sich mitunter ermuthigend und mit Erfolg zugerufen zu haben: "Es ist ein Traum! Ich will ihn weiter träumen!" Wie man mir auch von Personen erzählt hat, die die Causalität eines und desselben Traumes über drei und mehr aufeinanderfolgende Nächte hin fortzusetzen im Stande waren: Thatsachen, welche deutlich Zeugniss dafür abgeben, dass unser innerstes Wesen, der gemeinsame Untergrund von uns allen, mit tiefer Lust und freudiger Nothwendigkeit den Traum an sich erfährt.

- Thus the man who is responsive to artistic stimuli reacts to the reality of dreams as does the philosopher to the reality of existence; he observes closely, and he enjoys his observation: for it is out of these images that he interprets life, out of these processes that he trains himself for life. It is not only pleasant and agreeable images that he experiences with such universal understanding: the serious, the gloomy, the sad and the profound, the sudden restraints, the mockeries of chance, fearful expectations, in short the whole 'divine comedy' of life, the Inferno included, passes before him, not only as a shadow-play — for he too lives and suffers through these scenes — and yet also not without that fleeting sense of illusion; and perhaps many, like myself, can remember calling out to themselves in encouragement, amid the perils and terrors of the dream, and with success: 'It is a dream! I want to dream on!' Just as I have often been told of people who have been able to continue one and the same dream over three and more successive nights: facts which clearly show that our innermost being, our common foundation, experiences dreams with profound pleasure and joyful necessity.

- p. 15

- In diesen Sanct-Johann- und Sanct-Veittänzern erkennen wir die bacchischen Chöre der Griechen wieder, mit ihrer Vorgeschichte in Kleinasien, bis hin zu Babylon und den orgiastischen Sakäen. Es giebt Menschen, die, aus Mangel an Erfahrung oder aus Stumpfsinn, sich von solchen Erscheinungen wie von "Volkskrankheiten", spöttisch oder bedauernd im Gefühl der eigenen Gesundheit abwenden: die Armen ahnen freilich nicht, wie leichenfarbig und gespenstisch eben diese ihre "Gesundheit" sich ausnimmt, wenn an ihnen das glühende Leben dionysischer Schwärmer vorüberbraust.

- In these dancers of Saint John and Saint Vitus we can recognize the Bacchic choruses of the Greeks, with their prehistory in Asia Minor, as far back as Babylon and the orgiastic Sacaea. Some people, either through a lack of experience or through obtuseness, turn away with pity or contempt from phenomena such as these as from 'folk diseases', bolstered by a sense of their own sanity; these poor creatures have no idea how blighted and ghostly this 'sanity' of theirs sounds when the glowing life of Dionysiac revellers thunders past them.

- p. 17

- Es geht die alte Sage, dass König Midas lange Zeit nach dem weisen Silen, dem Begleiter des Dionysus, im Walde gejagt habe, ohne ihn zu fangen. Als er ihm endlich in die Hände gefallen ist, fragt der König, was für den Menschen das Allerbeste und Allervorzüglichste sei. Starr und unbeweglich schweigt der Dämon; bis er, durch den König gezwungen, endlich unter gellem Lachen in diese Worte ausbricht: `Elendes Eintagsgeschlecht, des Zufalls Kinder und der Mühsal, was zwingst du mich dir zu sagen, was nicht zu hören für dich das Erspriesslichste ist? Das Allerbeste ist für dich gänzlich unerreichbar: nicht geboren zu sein, nicht zu sein, nichts zu sein. Das Zweitbeste aber ist für dich - bald zu sterben.

- According to the old story, King Midas had long hunted wise Silenus, Dionysus' companion, without catching him. When Silenus had finally fallen into his clutches, the king asked him what was the best and most desirable thing of all for mankind. The daemon stood still, stiff and motionless, until at last, forced by the king, he gave a shrill laugh and spoke these words: 'Miserable, ephemeral race, children of hazard and hardship, why do you force me to say what it would be much more fruitful for you not to hear? The best of all things is something entirely outside your grasp: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second-best thing for you — is to die soon.'

- p. 22

- Der philosophische Mensch hat sogar das Vorgefühl, dass auch unter dieser Wirklichkeit, in der wir leben und sind, eine zweite ganz andre verborgen liege...

- Underneath this reality in which we live and have our being, another and altogether different reality lies concealed...

- p. 23, William Haussmann translation

- Mit dem Tode der griechischen Tragödie dagegen entstand eine ungeheure, überall tief empfundene Leere; wie einmal griechische Schiffer zu Zeiten des Tiberius an einem einsamen Eiland den erschütternden Schrei hörten "der grosse Pan ist todt": so klang es jetzt wie ein schmerzlicher Klageton durch die hellenische Welt: "die Tragödie ist todt! Die Poesie selbst ist mit ihr verloren gegangen! Fort, fort mit euch verkümmerten, abgemagerten Epigonen! Fort in den Hades, damit ihr euch dort an den Brosamen der vormaligen Meister einmal satt essen könnt!"

- Greek tragedy met her death in a different way from all the older sister arts: she died tragically by her own hand, after irresolvable conflicts, while the others died happy and peaceful at an advanced age. If a painless death, leaving behind beautiful progeny, is the sign of a happy natural state, then the endings of the other arts show us the example of just such a happy natural state: they sink slowly, and with their dying eyes they behold their fairer offspring, who lift up their heads in bold impatience. The death of Greek tragedy, on the other hand, left a great void whose effects were felt profoundly, far and wide; as once Greek sailors in Tiberius' time heard the distressing cry 'the god Pan is dead' issuing from a lonely island, now, throughout the Hellenic world, this cry resounded like an agonized lament: 'Tragedy is dead! Poetry itself died with it! Away, away with you, puny, stunted imitators! Away with you to Hades, and eat your fill of the old masters' crumbs!'

- p. 54

- Bei diesem Zusammenhange ist die leidenschaftliche Zuneigung begreiflich, welche die Dichter der neueren Komödie zu Euripides empfanden; so dass der Wunsch des Philemon nicht weiter befremdet, der sich sogleich aufhängen lassen mochte, nur um den Euripides in der Unterwelt aufsuchen zu können: wenn er nur überhaupt überzeugt sein dürfte, dass der Verstorbene auch jetzt noch bei Verstande sei.

- This context enables us to understand the passionate affection in which the poets of the New Comedy held Euripides; so that we are no longer startled by the desire of Philemon, who wished to be hanged at once so that he might meet Euripides in the underworld, so long as he could be sure that the deceased was still in full possession of his senses.

- p. 55

- ...aesthetischen Sokratismus...dessen oberstes Gesetz ungefähr so lautet: "alles muss verständig sein, um schön zu sein"; als Parallelsatz zu dem sokratischen "nur der Wissende ist tugendhaft."

- ...aesthetic Socratism, the chief law of which is, more or less: "to be beautiful everything must first be intelligible" — a parallel to the Socratic dictum: "only the one who knows is virtuous."

- p. 62

- Nun aber schien Sokrates die tragische Kunst nicht einmal "die Wahrheit zu sagen": abgesehen davon, dass sie sich an den wendet, der "nicht viel Verstand besitzt", also nicht an den Philosophen: ein zweifacher Grund, von ihr fern zu bleiben. Wie Plato, rechnete er sie zu den schmeichlerischen Künsten, die nur das Angenehme, nicht das Nützliche darstellen und verlangte deshalb bei seinen Jüngern Enthaltsamkeit und strenge Absonderung von solchen unphilosophischen Reizungen; mit solchem Erfolge, dass der jugendliche Tragödiendichter Plato zu allererst seine Dichtungen verbrannte, um Schüler des Sokrates werden zu können.

- But for Socrates, tragedy did not even seem to "tell what's true", quite apart from the fact that it addresses "those without much wit", not the philosopher: another reason for giving it a wide berth. Like Plato, he numbered it among the flattering arts which represent only the agreeable, not the useful, and therefore required that his disciples abstain most rigidly from such unphilosophical stimuli — with such success that the young tragedian, Plato, burnt his writings in order to become a pupil of Socrates.

- p. 68

- Darum hat Lessing, der ehrlichste theoretische Mensch, es auszusprechen gewagt, dass ihm mehr am Suchen der Wahrheit als an ihr selbst gelegen sei...

- Lessing, the most honest of theoretical men, dared to say that he took greater delight in the quest for truth than in the truth itself.

- p. 73

- ...der kann sich nicht entbrechen, in Sokrates den einen Wendepunkt und Wirbel der sogenannten Weltgeschichte zu sehen. Denn dächte man sich einmal diese ganze unbezifferbare Summe von Kraft, die für jene Welttendenz verbraucht worden ist, nicht im Dienste des Erkennens, sondern auf die praktischen d.h. egoistischen Ziele der Individuen und Völker verwendet, so wäre wahrscheinlich in allgemeinen Vernichtungskämpfen und fortdauernden Völkerwanderungen die instinctive Lust zum Leben so abgeschwächt, dass, bei der Gewohnheit des Selbstmordes, der Einzelne vielleicht den letzten Rest von Pflichtgefühl empfinden müsste, wenn er, wie der Bewohner der Fidschiinseln, als Sohn seine Eltern, als Freund seinen Freund erdrosselt: ein praktischer Pessimismus, der selbst eine grausenhafte Ethik des Völkermordes aus Mitleid erzeugen könnte - der übrigens überall in der Welt vorhanden ist und vorhanden war, wo nicht die Kunst in irgend welchen Formen, besonders als Religion und Wissenschaft, zum Heilmittel und zur Abwehr jenes Pesthauchs erschienen ist.

- We cannot help but see Socrates as the turning-point, the vortex of world history. For if we imagine that the whole incalculable store of energy used in that global tendency had been used not in the service of knowledge but in ways applied to the practical — selfish — goals of individuals and nations, universal wars of destruction and constant migrations of peoples would have enfeebled man's instinctive zest for life to the point where, suicide having become universal, the individual would perhaps feel a vestigial duty as a son to strangle his parents, or as a friend his friend, as the Fiji islanders do: a practical pessimism that could even produce a terrible ethic of genocide through pity, and which is, and always has been, present everywhere in the world where art has not in some form, particularly as religion and science, appeared as a remedy and means of prevention for this breath of pestilence.

- p. 73

- Aber wie verändert sich plötzlich jene eben so düster geschilderte Wildniss unserer ermüdeten Cultur, wenn sie der dionysische Zauber berührt! Ein Sturmwind packt alles Abgelebte, Morsche, Zerbrochne, Verkümmerte, hüllt es wirbelnd in eine rothe Staubwolke und trägt es wie ein Geier in die Lüfte. Verwirrt suchen unsere Blicke nach dem Entschwundenen: denn was sie sehen, ist wie aus einer Versenkung an's goldne Licht gestiegen, so voll und grün, so üppig lebendig, so sehnsuchtsvoll unermesslich. Die Tragödie sitzt inmitten dieses Ueberflusses an Leben, Leid und Lust, in erhabener Entzückung, sie horcht einem fernen schwermüthigen Gesange - er erzählt von den Müttern des Seins, deren Namen lauten: Wahn, Wille, Wehe. - Ja, meine Freunde, glaubt mit mir an das dionysische Leben und an die Wiedergeburt der Tragödie. Die Zeit des sokratischen Menschen ist vorüber: kränzt euch mit Epheu, nehmt den Thyrsusstab zur Hand und wundert euch nicht, wenn Tiger und Panther sich schmeichelnd zu euren Knien niederlegen. Jetzt wagt es nur, tragische Menschen zu sein: denn ihr sollt erlöst werden. Ihr sollt den dionysischen Festzug von Indien nach Griechenland geleiten! Rüstet euch zu hartem Streite, aber glaubt an die Wunder eures Gottes!

- But what changes come upon the weary desert of our culture, so darkly described, when it is touched by the magic of Dionysus! A storm seizes everything decrepit, rotten, broken, stunted; shrouds it in a whirling red cloud of dust and carries it into the air like a vulture. In vain confusion we seek for all that has vanished; for what we see has risen as if from beneath he earth into the gold light, so full and green, so luxuriantly alive, immeasurable and filled with yearning. Tragedy sits in sublime rapture amidst this abundance of life, suffering and delight, listening to a far-off, melancholy song which tells of the Mothers of Being, whose names are Delusion, Will, Woe. -

Yes, my friends, join me in my faith in this Dionysiac life and the rebirth of tragedy. The age of Socratic man is past: crown yourselves with ivy, grasp the thyrsus and do not be amazed if tigers and panthers lie down fawning at your feet. Now dare to be tragic men, for you will be redeemed. You shall join the Dionysiac procession from India to Greece! Gird yourselves for a hard battle, but have faith in the miracles of your god! - p. 98

- But what changes come upon the weary desert of our culture, so darkly described, when it is touched by the magic of Dionysus! A storm seizes everything decrepit, rotten, broken, stunted; shrouds it in a whirling red cloud of dust and carries it into the air like a vulture. In vain confusion we seek for all that has vanished; for what we see has risen as if from beneath he earth into the gold light, so full and green, so luxuriantly alive, immeasurable and filled with yearning. Tragedy sits in sublime rapture amidst this abundance of life, suffering and delight, listening to a far-off, melancholy song which tells of the Mothers of Being, whose names are Delusion, Will, Woe. -

Anti-Education (1872)

[edit]

1872 lectures "Gedanken über die Zukunft unserer Bildungsanstalten" [The future of our educational institutions] Translated by D. Searls (2015)

- Diese doppelte Selbständigkeit preist man mit Hochgefühl als ›akademische Freiheit‹: ... nur daß hinter beiden Gruppen in bescheidener Entfernung der Staat mit einer gewissen gespannten Aufsehermiene steht, um von Zeit zu Zeit daran zu erinnern, daß er Zweck, Ziel und Inbegriff der sonderbaren Sprech- und Hörprozedur sei.

- This independence is glorified as "academic freedom," ... except that in the background, a discreet distance away, stands the state watching with a certain supervisory look on its face, making sure to remind everybody from time to time that it is the aim, the purpose, the essence of this whole strange process.

- So ist langsam an Stelle einer tiefsinnigen Ausdeutung der ewig gleichen Probleme ein historisches, ja selbst ein philologisches Abwägen und Fragen getreten: was der und jener Philosoph gedacht habe oder nicht, oder ob die und jene Schrift ihm mit Recht zuzuschreiben sei oder gar ob diese oder jene Lesart den Vorzug verdiene. Zu einem derartigen neutralen Sichbefassen mit Philosophie werden jetzt unsere Studenten in den philosophischen Seminarien unserer Universitäten angereizt: weshalb ich mich längst gewöhnt habe, eine solche Wissenschaft als Abzweigung der Philologie zu betrachten und ihre Vertreter danach abzuschätzen, ob sie gute Philologen sind oder nicht. Demnach ist nun freilich die Philosophie selbst von der Universität verbannt: womit unsre erste Frage nach dem Bildungswert der Universitäten beantwortet ist.

- Philological considerations have slowly but surely taken the place of profound explorations of eternal problems. The question becomes: What did this or that philosopher think or not think? And is this or that text rightly ascribed to him or not? And even: Is this variant of a classical text preferable to that other? Students in university seminars today are encouraged to occupy themselves with such emasculated inquiries. As a result, of course, philosophy itself is banished from the university altogether.

- Not one of these nobly equipped young men has escaped the restless, exhausting, confusing, debilitating crisis of education. ... He feels that he cannot guide himself, cannot help himself—and then he dives hopelessly into the world of everyday life and daily routine, he is immersed in the most trivial activity possible, and his limbs grow weak and weary.

- Über Wahrheit und Lüge im außermoralischen Sinn (1873)

- Part 1.

- Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of "world history," but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die. One might invent such a fable, and yet he still would not have adequately illustrated how miserable, how shadowy and transient, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature. There were eternities during which it did not exist. And when it is all over with the human intellect, nothing will have happened.

- Variant translation: In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest and most mendacious minute of "world history" — yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die.

One might invent such a fable and still not have illustrated sufficiently how wretched, how shadowy and flighty, how aimless and arbitrary, the human intellect appears in nature. There have been eternities when it did not exist; and when it is done for again, nothing will have happened.

- Variant translation: In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest and most mendacious minute of "world history" — yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die.

- The pride connected with knowing and sensing lies like a blinding fog over the eyes and senses of men, thus deceiving them concerning the value of existence. For this pride contains within itself the most flattering estimation of the value of knowing. Deception is the most general effect of such pride, but even its most particular effects contain within themselves something of the same deceitful character.

- Deception, flattering, lying, deluding, talking behind the back, putting up a false front, living in borrowed splendor, wearing a mask, hiding behind convention, playing a role for others and for oneself — in short, a continuous fluttering around the solitary flame of vanity — is so much the rule and the law among men that there is almost nothing which is less comprehensible than how an honest and pure drive for truth could have arisen among them. They are deeply immersed in illusions and in dream images; their eyes merely glide over the surface of things and see "forms."

- Variant translation: The constant fluttering around the single flame of vanity is so much the rule and the law that almost nothing is more incomprehensible than how an honest and pure urge for truth could make its appearance among men.

- What does man actually know about himself? Is he, indeed, ever able to perceive himself completely, as if laid out in a lighted display case? Does nature not conceal most things from him — even concerning his own body — in order to confine and lock him within a proud, deceptive consciousness, aloof from the coils of the bowels, the rapid flow of the blood stream, and the intricate quivering of the fibers! She threw away the key.

- and woe betide fateful curiosity should it ever succeed in peering through a crack in the chamber of consciousness, out and down into the depths, and thus gain an intimation of the fact that humanity, in the indifference of its ignorance, rests on the pitiless, the greedy, the insatiable, the murderous—clinging in dreams, as it were, to the back of a tiger.

- The liar is a person who uses the valid designations, the words, in order to make something which is unreal appear to be real. He says, for example, "I am rich," when the proper designation for his condition would be "poor." He misuses fixed conventions by means of arbitrary substitutions or even reversals of names. If he does this in a selfish and moreover harmful manner, society will cease to trust him and will thereby exclude him. What men avoid by excluding the liar is not so much being defrauded as it is being harmed by means of fraud. Thus, even at this stage, what they hate is basically not deception itself, but rather the unpleasant, hated consequences of certain sorts of deception. It is in a similarly restricted sense that man now wants nothing but truth: he desires the pleasant, life-preserving consequences of truth. He is indifferent toward pure knowledge which has no consequences; toward those truths which are possibly harmful and destructive he is even hostilely inclined.

- Are designations congruent with things? Is language the adequate expression of all realities?

It is only by means of forgetfulness that man can ever reach the point of fancying himself to possess a "truth" of the grade just indicated. If he will not be satisfied with truth in the form of tautology, that is to say, if he will not be content with empty husks, then he will always exchange truths for illusions.

- The various languages placed side by side show that with words it is never a question of truth, never a question of adequate expression; otherwise, there would not be so many languages. The "thing in itself" (which is precisely what the pure truth, apart from any of its consequences, would be) is likewise something quite incomprehensible to the creator of language and something not in the least worth striving for. This creator only designates the relations of things to men, and for expressing these relations he lays hold of the boldest metaphors.' To begin with, a nerve stimulus is transferred into an image: first metaphor. The image, in turn, is imitated in a sound: second metaphor. And each time there is a complete overleaping of one sphere, right into the middle of an entirely new and different one.

- We believe that we know something about the things themselves when we speak of trees, colors, snow, and flowers; and yet we possess nothing but metaphors for things — metaphors which correspond in no way to the original entities.

- Every word instantly becomes a concept precisely insofar as it is not supposed to serve as a reminder of the unique and entirely individual original experience to which it owes its origin; but rather, a word becomes a concept insofar as it simultaneously has to fit countless more or less similar cases — which means, purely and simply, cases which are never equal and thus altogether unequal. Every concept arises from the equation of unequal things. Just as it is certain that one leaf is never totally the same as another, so it is certain that the concept "leaf" is formed by arbitrarily discarding these individual differences and by forgetting the distinguishing aspects.

- We obtain the concept, as we do the form, by overlooking what is individual and actual; whereas nature is acquainted with no forms and no concepts, and likewise with no species, but only with an X which remains inaccessible and undefinable for us.

- Was ist also Wahrheit? Ein bewegliches Heer von Metaphern, Metonymien, Anthropomorphismen, kurz eine Summe von menschlichen Relationen, die, poetisch und rhetorisch gesteigert, übertragen, geschmückt wurden, und die nach langem Gebrauch einem Volke fest, kanonisch und verbindlich dünken: die Wahrheiten sind Illusionen, von denen man vergessen hat, daß sie welche sind, Metaphern, die abgenutzt und sinnlich kraftlos geworden sind, Münzen, die ihr Bild verloren haben und nun als Metall, nicht mehr als Münzen, in Betracht kommen.

- What then is truth? A movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long usage, seem to a people to be fixed, canonical, and binding. Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions — they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins.

- We still do not yet know where the drive for truth comes from. For so far we have heard only of the duty which society imposes in order to exist: to be truthful means to employ the usual metaphors. Thus, to express it morally, this is the duty to lie according to a fixed convention, to lie with the herd and in a manner binding upon everyone. Now man of course forgets that this is the way things stand for him. Thus he lies in the manner indicated, unconsciously and in accordance with habits which are centuries' old; and precisely by means of this unconsciousness and forgetfulness he arrives at his sense of truth.

- The venerability, reliability, and utility of truth is something which a person demonstrates for himself from the contrast with the liar, whom no one trusts and everyone excludes. As a "rational" being, he now places his behavior under the control of abstractions. He will no longer tolerate being carried away by sudden impressions, by intuitions.

- Everything which distinguishes man from the animals depends upon this ability to volatilize perceptual metaphors in a schema, and thus to dissolve an image into a concept. For something is possible in the realm of these schemata which could never be achieved with the vivid first impressions: the construction of a pyramidal order according to castes and degrees, the creation of a new world of laws, privileges, subordinations, and clearly marked boundaries — a new world, one which now confronts that other vivid world of first impressions as more solid, more universal, better known, and more human than the immediately perceived world, and thus as the regulative and imperative world.

- One may certainly admire man as a mighty genius of construction, who succeeds in piling an infinitely complicated dome of concepts upon an unstable foundation, and, as it were, on running water. Of course, in order to be supported by such a foundation, his construction must be like one constructed of spiders' webs: delicate enough to be carried along by the waves, strong enough not to be blown apart by every wind.

- As a genius of construction man raises himself far above the bee in the following way: whereas the bee builds with wax that he gathers from nature, man builds with the far more delicate conceptual material which he first has to manufacture from himself.

- When someone hides something behind a bush and looks for it again in the same place and finds it there as well, there is not much to praise in such seeking and finding. Yet this is how matters stand regarding seeking and finding "truth" within the realm of reason. If I make up the definition of a mammal, and then, after inspecting a camel, declare "look, a mammal' I have indeed brought a truth to light in this way, but it is a truth of limited value. That is to say, it is a thoroughly anthropomorphic truth which contains not a single point which would be "true in itself" or really and universally valid apart from man. At bottom, what the investigator of such truths is seeking is only the metamorphosis of the world into man.

- Only by forgetting this primitive world of metaphor can one live with any repose, security, and consistency: only by means of the petrification and coagulation of a mass of images which originally streamed from the primal faculty of human imagination like a fiery liquid, only in the invincible faith that this sun, this window, this table is a truth in itself, in short, only by forgetting that he himself is an artistically creating subject, does man live with any repose, security, and consistency. If but for an instant he could escape from the prison walls of this faith, his "self consciousness" would be immediately destroyed. It is even a difficult thing for him to admit to himself that the insect or the bird perceives an entirely different world from the one that man does, and that the question of which of these perceptions of the world is the more correct one is quite meaningless, for this would have to have been decided previously in accordance with the criterion of the correct perception, which means, in accordance with a criterion which is not available.

- Between two absolutely different spheres, as between subject and object, there is no causality, no correctness, and no expression; there is, at most, an aesthetic relation: I mean, a suggestive transference, a stammering translation into a completely foreign tongue — for which I there is required, in any case, a freely inventive intermediate sphere and mediating force. "Appearance" is a word that contains many temptations, which is why I avoid it as much as possible. For it is not true that the essence of things "appears" in the empirical world. A painter without hands who wished to express in song the picture before his mind would, by means of this substitution of spheres, still reveal more about the essence of things than does the empirical world. Even the relationship of a nerve stimulus to the generated image is not a necessary one. But when the same image has been generated millions of times and has been handed down for many generations and finally appears on the same occasion every time for all mankind, then it acquires at last the same meaning for men it would have if it were the sole necessary image and if the relationship of the original nerve stimulus to the generated image were a strictly causal one. In the same manner, an eternally repeated dream would certainly be felt and judged to be reality. But the hardening and congealing of a metaphor guarantees absolutely nothing concerning its necessity and exclusive justification.

- If each us had a different kind of sense perception — if we could only perceive things now as a bird, now as a worm, now as a plant, or if one of us saw a stimulus as red, another as blue, while a third even heard the same stimulus as a sound — then no one would speak of such a regularity of nature, rather, nature would be grasped only as a creation which is subjective in the highest degree. After all, what is a law of nature as such for us? We are not acquainted with it in itself, but only with its effects, which means in its relation to other laws of nature — which, in turn, are known to us only as sums of relations. Therefore all these relations always refer again to others and are thoroughly incomprehensible to us in their essence.

- We produce these representations in and from ourselves with the same necessity with which the spider spins. If we are forced to comprehend all things only under these forms, then it ceases to be amazing that in all things we actually comprehend nothing but these forms. For they must all bear within themselves the laws of number, and it is precisely number which is most astonishing in things. All that conformity to law, which impresses us so much in the movement of the stars and in chemical processes, coincides at bottom with those properties which we bring to things. Thus it is we who impress ourselves in this way

- Part 2

- We have seen how it is originally language which works on the construction of concepts, a labor taken over in later ages by science. Just as the bee simultaneously constructs cells and fills them with honey, so science works unceasingly on this great columbarium of concepts, the graveyard of perceptions.

- Whereas the man of action binds his life to reason and its concepts so that he will not be swept away and lost, the scientific investigator builds his hut right next to the tower of science so that he will be able to work on it and to find shelter for himself beneath those bulwarks which presently exist. And he requires shelter, for there are frightful powers which continuously break in upon him, powers which oppose scientific "truth" with completely different kinds of "truths" which bear on their shields the most varied sorts of emblems.

- The drive toward the formation of metaphors is the fundamental human drive, which one cannot for a single instant dispense with in thought, for one would thereby dispense with man himself. This drive is not truly vanquished and scarcely subdued by the fact that a regular and rigid new world is constructed as its prison from its own ephemeral products, the concepts. It seeks a new realm and another channel for its activity, and it finds this in myth and in art generally. This drive continually confuses the conceptual categories and cells by bringing forward new transferences, metaphors, and metonymies. It continually manifests an ardent desire to refashion the world which presents itself to waking man, so that it will be as colorful, irregular, lacking in results and coherence, charming, and eternally new as the world of dreams. Indeed, it is only by means of the rigid and regular web of concepts that the waking man clearly sees that he is awake; and it is precisely because of this that he sometimes thinks that he must be dreaming when this web of concepts is torn by art.

- Because of the way that myth takes it for granted that miracles are always happening, the waking life of a mythically inspired people — the ancient Greeks, for instance — more closely resembles a dream than it does the waking world of a scientifically disenchanted thinker.

- Man has an invincible inclination to allow himself to be deceived and is, as it were, enchanted with happiness when the rhapsodist tells him epic fables as if they were true, or when the actor in the theater acts more royally than any real king. So long as it is able to deceive without injuring, that master of deception, the intellect, is free; it is released from its former slavery and celebrates its Saturnalia. It is never more luxuriant, richer, prouder, more clever and more daring.

- That immense framework and planking of concepts to which the needy man clings his whole life long in order to preserve himself is nothing but a scaffolding and toy for the most audacious feats of the liberated intellect. And when it smashes this framework to pieces, throws it into confusion, and puts it back together in an ironic fashion, pairing the most alien things and separating the closest, it is demonstrating that it has no need of these makeshifts of indigence and that it will now be guided by intuitions rather than by concepts. There is no regular path which leads from these intuitions into the land of ghostly schemata, the land of abstractions. There exists no word for these intuitions; when man sees them he grows dumb, or else he speaks only in forbidden metaphors and in unheard — of combinations of concepts. He does this so that by shattering and mocking the old conceptual barriers he may at least correspond creatively to the impression of the powerful present intuition.

- There are ages in which the rational man and the intuitive man stand side by side, the one in fear of intuition, the other with scorn for abstraction. The latter is just as irrational as the former is inartistic. They both desire to rule over life: the former, by knowing how to meet his principle needs by means of foresight, prudence, and regularity; the latter, by disregarding these needs and, as an "overjoyed hero," counting as real only that life which has been disguised as illusion and beauty.

- The man who is guided by concepts and abstractions only succeeds by such means in warding off misfortune, without ever gaining any happiness for himself from these abstractions. And while he aims for the greatest possible freedom from pain, the intuitive man, standing in the midst of a culture, already reaps from his intuition a harvest of continually inflowing illumination, cheer, and redemption — in addition to obtaining a defense against misfortune. To be sure, he suffers more intensely, when he suffers; he even suffers more frequently, since he does not understand how to learn from experience and keeps falling over and over again into the same ditch.

Untimely Meditations (1876)

[edit]

- Um aber unsere Klassiker so falsch beurteilen und so beschimpfend ehren zu können, muß man sie gar nicht mehr kennen: und dies ist die allgemeine Tatsache. Denn sonst müßte man wissen, daß es nur eine Art gibt, sie zu ehren, nämlich dadurch, daß man fortfährt, in ihrem Geiste und mit ihrem Mute zu suchen, und dabei nicht müde wird.

- In order to be able thus to misjudge, and thus to grant left-handed veneration to our classics, people must have ceased to know them. This, generally speaking, is precisely what has happened. For, otherwise, one ought to know that there is only one way of honoring them, and that is to continue seeking with the same spirit and with the same courage, and not to weary of the search.

- (A. Ludovici trans.), § 1.2

- [Philistines] only devised the notion of an epigone-age in order to secure peace for themselves, and to be able to reject all the efforts of disturbing innovators summarily as the work of epigones. With the view of ensuring their own tranquility, these smug ones even appropriated history, and sought to transform all sciences that threatened to disturb their wretched ease into branches of history. ... No, in their desire to acquire an historical grasp of everything, stultification became the sole aim of these philosophical admirers of “nil admirari.” While professing to hate every form of fanaticism and intolerance, what they really hated, at bottom, was the dominating genius and the tyranny of the real claims of culture.

- (A. Ludovici trans.), “David Strauss,” § 1.2

- In this way, a philosophy which veiled the Philistine confessions of its founder beneath neat twists and flourishes of language proceeded further to discover a formula for the canonization of the commonplace. It expatiated upon the rationalism of all reality, and thus ingratiated itself with the Culture-Philistine, who also loves neat twists and flourishes, and who, above all, considers himself real, and regards his reality as the standard of reason for the world. From this time forward he began to allow every one, and even himself, to reflect, to investigate, to aestheticise, and, more particularly, to make poetry, music, and even pictures—not to mention systems of philosophy; provided, of course, that ... no assault were made upon the “reasonable” and the “real”—that is to say, upon the Philistine.

- (A. Ludovici trans.), “David Strauss,” § 1.2, p. 17

- I do not know what meaning classical studies could have for our time if they were not untimely—that is to say, acting counter to our time and thereby acting on our time and, let us hope, for the benefit of a time to come.

- “On the uses and disadvantages of history for life,” R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), § 2.0, p. 60

- Perhaps no philosopher is more correct than the cynic. The happiness of the animal, that thorough cynic, is the living proof of cynicism.

- § 2.1, cited in Peter Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason (1987), p. ix

- In his heart every man knows quite well that, being unique, he will be in the world only once and that no imaginable chance will for a second time gather together into a unity so strangely variegated an assortment as he is: he knows it but he hides it like a bad conscience—why? From fear of his neighbor, who demands conventionality and cloaks himself with it. But what is it that constrains the individual to fear his neighbor, to think and act like a member of a herd, and to have no joy in himself? Modesty, perhaps, in a few rare cases. With the great majority it is indolence, inertia. ... Men are even lazier than they are timid, and fear most of all the inconveniences with which unconditional honesty and nakedness would burden them. Artists alone hate this sluggish promenading in borrowed fashions and appropriated opinions and they reveal everyone's secret bad conscience, the law that every man is a unique miracle.

- “Schopenhauer as educator” ("Schopenhauer als Erzieher"), § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 127

- The man who does not wish to belong to the mass needs only to cease taking himself easily; let him follow his conscience, which calls to him: “Be your self! All you are now doing, thinking, desiring, is not you yourself.”

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 127

- Es gibt kein öderes und widrigeres Geschöpf in der Natur als den Menschen, welcher seinem Genius ausgewichen ist und nun nach rechts und nach links, nach rückwärts und überallhin schielt. Man darf einen solchen Menschen zuletzt gar nicht mehr angreifen, denn er ist ganz Außenseite ohne Kern, ein anbrüchiges, gemaltes, aufgebauschtes Gewand.

- There exists no more repulsive and desolate creature in the world than the man who has evaded his genius and who now looks furtively to left and right, behind him and all about him. In the end such a man becomes impossible to get hold of, since he is wholly exterior, without kernel: a tattered, painted bag of clothes; a decked-out ghost that cannot inspire even fear and certainly not pity.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 128

- There exists no more repulsive and desolate creature in the world than the man who has evaded his genius and who now looks furtively to left and right, behind him and all about him. In the end such a man becomes impossible to get hold of, since he is wholly exterior, without kernel: a tattered, painted bag of clothes; a decked-out ghost that cannot inspire even fear and certainly not pity.

- Wenn man mit Recht vom Faulen sagt, er töte die Zeit, so muß man von einer Periode, welche ihr Heil auf die öffentlichen Meinungen, das heißt auf die privaten Faulheiten setzt, ernstlich besorgen, daß eine solche Zeit wirklich einmal getötet wird: ich meine, daß sie aus der Geschichte der wahrhaften Befreiung des Lebens gestrichen wird. Wie groß muß der Widerwille späterer Geschlechter sein, sich mit der Hinterlassenschaft jener Periode zu befassen, in welcher nicht die lebendigen Menschen, sondern öffentlich meinende Scheinmenschen regierten.

- If it is true to say of the lazy that they kill time, then it is greatly to be feared that an era which sees its salvation in public opinion, this is to say private laziness, is a time that really will be killed: I mean that it will be struck out of the history of the true liberation of life. How reluctant later generations will be to have anything to do with the relics of an era ruled, not by living men, but by pseudo-men dominated by public opinion.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 128

- If it is true to say of the lazy that they kill time, then it is greatly to be feared that an era which sees its salvation in public opinion, this is to say private laziness, is a time that really will be killed: I mean that it will be struck out of the history of the true liberation of life. How reluctant later generations will be to have anything to do with the relics of an era ruled, not by living men, but by pseudo-men dominated by public opinion.

- Wir haben uns über unser Dasein vor uns selbst zu verantworten; folglich wollen wir auch die wirklichen Steuermänner dieses Daseins abgeben und nicht zulassen, daß unsre Existenz einer gedankenlosen Zufälligkeit gleiche.

- We are responsible to ourselves for our own existence; consequently we want to be the true helmsman of this existence and refuse to allow our existence to resemble a mindless act of chance.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 128

- We are responsible to ourselves for our own existence; consequently we want to be the true helmsman of this existence and refuse to allow our existence to resemble a mindless act of chance.

- I will make an attempt to attain freedom, the youthful soul says to itself; and is it to be hindered in this by the fact that two nations happen to hate and fight one another, or that two continents are separated by an ocean, or that all around it a religion is taught with did not yet exist a couple of thousand years ago. All that is not you, it says to itself.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 128

- Niemand kann dir die Brücke bauen, auf der gerade du über den Fluß des Lebens schreiten mußt, niemand außer dir allein.

- No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 129

- No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.

- Es gibt in der Welt einen einzigen Weg, auf welchem niemand gehen kann, außer dir: wohin er führt? Frage nicht, gehe ihn.

- There exists in the world a single path along which no one can go except you: whither does it lead? Do not ask, go along it.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 129

- There exists in the world a single path along which no one can go except you: whither does it lead? Do not ask, go along it.

- Wie finden wir uns selbst wieder? Wie kann sich der Mensch kennen? Er ist eine dunkle und verhüllte Sache; und wenn der Hase sieben Häute hat, so kann der Mensch sich sieben mal siebzig abziehn und wird noch nicht sagen können: »das bist du nun wirklich, das ist nicht mehr Schale«.

- How can a man know himself? He is a thing dark and veiled; and if the hare has seven skins, man can slough off seventy times seven and still not be able to say: “this is really you, this is no longer outer shell.”

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 129

- How can a man know himself? He is a thing dark and veiled; and if the hare has seven skins, man can slough off seventy times seven and still not be able to say: “this is really you, this is no longer outer shell.”

- Das ist das Geheimnis aller Bildung: sie verleiht nicht künstliche Gliedmaßen, wächserne Nasen, bebrillte Augen – vielmehr ist das, was diese Gaben zu geben vermöchte, nur das Afterbild der Erziehung. Sondern Befreiung ist sie, Wegräumung alles Unkrauts, Schuttwerks, Gewürms, das die zarten Keime der Pflanzen antasten will.

- That is the secret of all culture: it does not provide artificial limbs, wax noses or spectacles—that which can provide these things is, rather, only sham education. Culture is liberation, the removal of all the weeds, rubble and vermin that want to attack the tender buds of the plant.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.1, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), p. 130

- That is the secret of all culture: it does not provide artificial limbs, wax noses or spectacles—that which can provide these things is, rather, only sham education. Culture is liberation, the removal of all the weeds, rubble and vermin that want to attack the tender buds of the plant.

- Compare: "Truth that has been merely learned is like an artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose; at best, like a nose made out of another's flesh; it adheres to us only because it is put on."—Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. 2, Ch. 22, § 261

- I always believed that at some time fate would take from me the terrible effort and duty of educating myself. I believed that, when the time came, I would discover a philosopher to educate me, a true philosopher whom one could follow without any misgiving because one would have more faith in him than one had in oneself. Then I asked myself: what would be the principles by which he would educate you?—and I reflected on what he might say about the two educational maxims which are being hatched in our time. One of them demands that the educator should quickly recognize the real strength of his pupil and then direct all his efforts and energy and heat at them so as to help that one virtue to attain true maturity and fruitfulness. The other maxim, on the contrary, requires that the educator should draw forth and nourish all the forces which exist in his pupil and bring them to a harmonious relationship with one another. ... But where do we discover a harmonious whole at all, a simultaneous sounding of many voice in one nature, if not in such men as Cellini, men in whom everything, knowledge, desire, love, hate, strives towards a central point, a root force, and where a harmonious system is constructed through the compelling domination of this living centre? And so perhaps these two maxims are not opposites at all? Perhaps the one simply says that man should have a center and the other than he should also have a periphery? That educating philosopher of whom I dreamed would, I came to think, not only discover the central force, he would also know how to prevent its acting destructively on the other forces: his educational task would, it seemed to me, be to mould the whole man into a living solar and planetary system and to understand its higher laws of motion.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.2, R. Hollingdale, trans. (1983), pp. 130-131

- Die gebildeten Stände und Staaten werden von einer großartig verächtlichen Geldwirtschaft fortgerissen. Niemals war die Welt mehr Welt, nie ärmer an Liebe und Güte.

- The civilized classes and nations are swept away by the grand rush for contemptible wealth. Never was the world worldlier, never was it emptier of love and goodness.

- “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.4

- The civilized classes and nations are swept away by the grand rush for contemptible wealth. Never was the world worldlier, never was it emptier of love and goodness.

- Where there have been powerful governments, societies, religions, public opinions, in short wherever there has been tyranny, there the solitary philosopher has been hated; for philosophy offers an asylum to a man into which no tyranny can force it way, the inward cave, the labyrinth of the heart.

- trans. Hollingdale, “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.3, p. 139

- These people who have fled inward for their freedom also have to live outwardly, become visible, let themselves be seen; they are united with mankind through countless ties of blood, residence, education, fatherland, chance, the importunity of others; they are likewise presupposed to harbour countless opinions simply because these are the ruling opinions of the time; every gesture which is not clearly a denial counts as agreement.

- trans. Hollingdale, “Schopenhauer as educator,” § 3.3, p. 139

- All that exists that can be denied deserves to be denied; and being truthful means: to believe in an existence that can in no way be denied and which is itself true and without falsehood.

- trans. Hollingdale, “Schopenhauer as educator,” p. 153

- The objective of all human arrangements is through distracting one's thoughts to cease to be aware of life.

- trans. Hollingdale (1983), “Schopenhauer as educator,” p. 154

- Haste is universal because everyone is in flight from himself.

- trans. Hollingdale (1983), “Schopenhauer as educator,” p. 158

Human, All Too Human (1878)

[edit]

- Menschliches, Allzumenschliches

- Life is, after all, not a product of morality.

- Preface 1, tr. R.J. Hollingdale. The German original has slightly other meaning: "das Leben ist nun einmal nicht von der Moral ausgedacht" ("...and the life was not invented, one day, by morality").

- Our destiny exercises its influence over us even when, as yet, we have not learned its nature: it is our future that lays down the law of our today.

- Preface 7

- One common false conclusion is that because someone is truthful and upright towards us he is spreading the truth. Thus the child believes his parents' judgements, the Christian believes the claims of the church's founders. Likewise, people do not want to admit that all those things which men defended with the sacrifice of their lives and happiness in earlier centuries were nothing but errors.

- I.53

- No power can maintain itself if only hypocrites represent it.

- I. 55

- One must have a good memory to be able to keep the promises one makes.

- I.59

- ... die Hoffnung: sie ist in Wahrheit das übelste der Übel, weil sie die Qual der Menschen verlängert.

- In reality, hope is the worst of all evils, because it prolongs man's torments.

- I.71

- One will rarely err if extreme actions be ascribed to vanity, ordinary actions to habit, and mean actions to fear.

- I.74

- When virtue has slept, she will get up more refreshed.

- I.83

- Most men are too concerned with themselves to be malicious.

- I.85

- He who humbleth himself wants to be exalted.

- I.87

- Every tradition grows ever more venerable — the more remote its origin, the more confused that origin is. The reverence due to it increases from generation to generation. The tradition finally becomes holy and inspires awe.

- I.96

- Thoughts in a poem. The poet presents his thoughts festively, on the carriage of rhythm: usually because they could not walk.

- 1.189

- Where there is happiness, there is found pleasure in nonsense. The transformation of experience into its opposite, of the suitable into the unsuitable, the obligatory into the optional (but in such a manner that this process produces no injury and is only imagined in jest), is a pleasure; ...

- I.213

- Main deficiency of active people. Active men are usually lacking in higher activity--I mean individual activity. They are active as officials, businessmen, scholars, that is, as generic beings, but not as quite particular, single and unique men. In this respect they are lazy.

- It is the misfortune of active men that their activity is almost always a bit irrational. For example, one must not inquire of the money-gathering banker what the purpose for his restless activity is: it is irrational. Active people roll like a stone, conforming to the stupidity of mechanics.

- Today as always, men fall into two groups: slaves and free men. Whoever does not have two-thirds of his day for himself, is a slave, whatever he may be: a statesman, a businessman, an official, or a scholar.

- We often contradict an opinion for no other reason than that we do not like the tone in which it is expressed.

- Arrogance on the part of the meritorious is even more offensive to us than the arrogance of those without merit: for merit itself is offensive.

- Unpleasant, even dangerous, qualities can be found in every nation and every individual: it is cruel to demand that the Jew be an exception. In him, these qualities may even be dangerous and revolting to an unusual degree; and perhaps the young stock-exchange Jew is altogether the most disgusting invention of mankind.

- I.475

- He who thinks a great deal is not suited to be a party man: he thinks his way through the party and out the other side too soon.

- I.579

- Socialism itself can hope to exist only for brief periods here and there, and then only through the exercise of the extremest terrorism. For this reason it is secretly preparing itself for rule through fear and is driving the word 'justice' into the heads of the half-educated masses like a nail so as to rob them of their reason... and to create in them a good conscience for the evil game they are to play.

- Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 173-174

- The advantage of a bad memory is that one can enjoy the same good things for the first time several times.

- I.580

- No one talks more passionately about his rights than he who in the depths of his soul doubts whether he has any. By enlisting passion on his side he wants to stifle his reason and its doubts: thus he will acquire a good conscience and with it success among his fellow men.

- I.597

- If you have hitherto believed that life was one of the highest value and now see yourselves disappointed, do you at once have to reduce it to the lowest possible price?

- II.1

- Die mutter der Ausschweifung ist nicht die Freude, sondern die Freudlosigkeit.[1]

- The mother of excess is not joy but joylessness.[2]

- II.77

- Mancher wird nur deshalb kein Denker, weil sein Gedächtnis zu gut ist.

- Many a man fails to become a thinker only because his memory is too good.

- II.122

- The worst readers are those who behave like plundering troops: they take away a few things they can use, dirty and confound the remainder, and revile the whole.

- II.137

- A witticism is an epigram on the death of a feeling.

- II.202

- Forgetting our intentions is the most frequent of all acts of stupidity.

- II.206

- A Path to Equality. - A few hours of mountain climbing turn a rascal and a saint into two pretty similar creatures. Fatigue is the shortest way to Equality and Fraternity--and, in the end, Liberty will surrender to Sleep.

- II.263

- It says nothing against the ripeness of a spirit that it has a few worms.

- II.353

- With all great deceivers there is a noteworthy occurrence to which they owe their power. In the actual act of deception... they are overcome by belief in themselves. It is this which then speaks so miraculously and compellingly to those who surround them.[specific citation needed]

- Im Gebirge der Wahrheit kletterst du nie umsonst: Entweder du kommst schon heute weiter hinauf oder übst deine Kräfte, um morgen höher steigen zu können.

- In the mountains of truth you will never climb in vain: either you will get up higher today or you will exercise your strength so as to be able to get up higher tomorrow.

- It is mere illusion and pretty sentiment to expect much from mankind if he forgets how to make war. And yet no means are known which call so much into action as a great war, that rough energy born of the camp, that deep impersonality born of hatred, that conscience born of murder and cold-bloodedness, that fervor born of effort of the annihilation of the enemy, that proud indifference to loss, to one's own existence, to that of one's fellows, to that earthquake-like soul-shaking that a people needs when it is losing its vitality.[specific citation needed]

Helen Zimmern translation

[edit]

- (1909-1913)

- Feinde der Wahrheit. - Überzeugungen sind gefährlichere Feinde der Wahrheit, als Lügen.

- Ziel und Wege. - Viele sind hartnäckig in Bezug auf den einmal eingeschlagenen Weg, Wenige in Bezug auf das Ziel.

- Destination and paths. Many people are obstinate about the path once it is taken, few people about the destination.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 494

- Das Empörende an einer individuellen Lebensart. - Alle sehr individuellen Maassregeln des Lebens bringen die Menschen gegen Den, der sie ergreift, auf; sie fühlen sich durch die aussergewöhnliche Behandlung, welche jener sich angedeihen lässt, erniedrigt, als gewöhnliche Wesen.

- The infuriating thing about an individual way of living. People are always angry at anyone who chooses very individual standards for his life; because of the extraordinary treatment which that man grants to himself, they feel degraded, like ordinary beings.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 495

- Vorrecht der Grösse. - Es ist das Vorrecht der Grösse, mit geringen Gaben hoch zu beglücken.

- Privilege of greatness. It is the privilege of greatness to grant supreme pleasure through trifling gifts.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 496

- Jeder in Einer Sache überlegen. - In civilisirten Verhältnissen fühlt sich Jeder jedem Anderen in Einer Sache wenigstens überlegen: darauf beruht das allgemeine Wohlwollen, insofern Jeder einer ist, der unter Umständen helfen kann und desshalb sich ohne Scham helfen lassen darf.

- Everyone superior in one thing. In civilized circumstances, everyone feels superior to everyone else in at least one way; this is the basis of the general goodwill, inasmuch as everyone is someone who, under certain conditions, can be of help, and need therefore feel no shame in allowing himself to be helped.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 509

- Das Leben als Ertrag des Lebens. - Der Mensch mag sich noch so weit mit seiner Erkenntniss ausrecken, sich selber noch so objectiv vorkommen: zuletzt trägt er doch Nichts davon, als seine eigene Biographie.

- Life as the product of life. However far man may extend himself with his knowledge, however objective he may appear to himself - ultimately he reaps nothing but his own biography.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 513

- Aus der Erfahrung. - Die Unvernunft einer Sache ist kein Grund gegen ihr Dasein, vielmehr eine Bedingung desselben.

- From experience. That something is irrational is no argument against its existence, but rather a condition for it.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 515

- Gefahr unserer Cultur. - Wir gehören einer Zeit an, deren Cultur in Gefahr ist, an den Mitteln der Cultur zu Grunde zu gehen.

- Danger of our culture. We belong to a time in which culture is in danger of being destroyed by the means of culture.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 520

- Die Länge des Tages. - Wenn man viel hineinzustecken hat, so hat ein Tag hundert Taschen.

- The day's length. If a man has a great deal to put in them, a day will have a hundred pockets.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 529

- Unglück. - Die Auszeichnung, welche im Unglück liegt (als ob es ein Zeichen von Flachheit, Anspruchslosigkeit, Gewöhnlichkeit sei, sich glücklich zu fühlen), ist so gross, dass wenn Jemand Einem sagt: "Aber wie glücklich Sie sind!" man gewöhnlich protestirt.

- Unhappiness. The distinction that lies in being unhappy (as if to feel happy were a sign of shallowness, lack of ambition, ordinariness) is so great that when someone says, "But how happy you must be!" we usually protest.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 534

- Den Andern zum Vorbild. - Wer ein gutes Beispiel geben will, muss seiner Tugend einen Gran Narrheit zusetzen: dann ahmt man nach und erhebt sich zugleich über den Nachgeahmten, - was die Menschen lieben.

- Model for others. He who wants to set a good example must add a grain of foolishness to his virtue; then others can imitate and, at the same time, rise above the one being imitated - something which people love.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 561

- Schatten in der Flamme. - Die Flamme ist sich selber nicht so hell, als den Anderen, denen sie leuchtet: so auch der Weise.

- Shadow in the flame. The flame is not so bright to itself as to those on whom it shines: so too the wise man.

- Section IX, "Man Alone with Himself" / aphorism 570