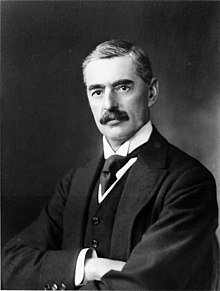

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (18 March 1869 – 9 November 1940) was a British politician. After a period as Lord Mayor of Birmingham, he entered national politics and was Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1929 to 1931. During the National Government of Ramsay MacDonald, Chamberlain served as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He later succeeded Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in 1937. Chamberlain negotiated the Munich Agreement with Adolf Hitler (Hitler never intended to honour it) and declared war in September 1939 owing to a mutual defence pact with Poland, which Hitler's Germany had invaded. He was forced to resign after the Norway Debate eight months into World War II and was replaced by Winston Churchill, who had been a leading critic of Chamberlain's foreign policy of appeasement. Since his death, Chamberlain has been viewed highly unfavorably among the general public, journalists, and politicians due to his foreign policy and handling of the war, although historians remain divided on whether this reputation is warranted.

Quotes

[edit]

Minister of Health

[edit]- In common with my colleagues, I recognise that no single remedy can be a complete cure, but while I am ready to examine every proposal...I must frankly say that I believe a tariff levied on imported foreign goods will be found to be indispensable... The ultimate destiny of this country is bound up with the Empire... I hope to take my part in forwarding a policy which was the main subject of my father's last great political campaign... I hope that we may presently develop into a National Party, and get rid of that odious title of Conservative, which has kept so many from joining us in the past.

- Election address in Birmingham (October 1931), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), pp. 196-197

Chancellor of the Exchequer

[edit]- There can have been few occasions in all our long political history when to the son of a man who counted for something in his day and generation has been vouchsafed the privilege of setting the seal on the work which the father began but had perforce to leave unfinished. Nearly 29 years have passed since Joseph Chamberlain entered upon his great campaign in favour of Imperial Preference and Tariff Reform. More than 17 years have gone by since he died, without having seen the fulfilment of his aims and yet convinced that, if not exactly in his way, yet in some modified form his vision would eventually take shape. His work was not in vain. Time and the misfortunes of the country have brought conviction to many who did not feel that they could agree with him then. I believe he would have found consolation for the bitterness of his disappointment if he could have foreseen that these proposals, which are the direct and legitimate descendants of his own conception, would be laid before the House of Commons, which he loved, in the presence of one and by the lips of the other of the two immediate successors to his name and blood.

- Speech in the House of Commons introducing the Import Duties Bill (4 February 1932)

- Of all countries passing through these difficult times the one that has stood the test with the greatest measure of success is the United Kingdom. Without underrating the hardships of our situation—the long tragedy of the unemployed, the grievous burden of taxation, the arduous and painful struggle of those engaged in trade and industry—at any rate we are free from that fear, which besets so many less fortunately placed, the fear that things are going to get worse. We owe our freedom from that fear largely to the fact that we have balanced our Budget.

- Budget speech in the House of Commons (25 April 1933)

- In 1932 many dark clouds still hung round the horizon. In 1933, although the outlook was distinctly brighter, there was no settled feeling that we were about to enjoy a spell of fine weather. To-day the atmosphere is distinctly brighter. The events of the last 12 months have shown gratifying evidence that the efforts of His Majesty's Government are bearing fruit... If you look to what I might call the telltale statistics, the unemployment figures and statistics of such things as retail trade, consumption of electricity, transport, iron and steel production and house building, in every case you see a definite revival of activity... If I might borrow an illustration from the titles of two well-known works of fiction, I would say that we have now finished the story of Bleak House and that we are sitting down this afternoon to enjoy the first chapter of Great Expectations.

- Budget speech in the House of Commons (17 April 1934)

- The Labour Party, obviously intends to fasten upon our backs the accusation of being 'warmongers' and they are suggesting that we have 'hush hush' plans for rearmament which we are concealing from the people. As a matter of fact we are working on plans for rearmament at an early date for the situation in Europe is most alarming... We are not sufficiently advanced to reveal our ideas to the public, but of course we cannot deny the general charge of rearmament and no doubt if we try to keep our ideas secret till after the election, we should either fail, or if we succeeded, lay ourselves open to the far more damaging accusation that we had deliberately deceived the people... I have therefore suggested that we should take the bold course of actually appealing to the country on a defence programme, thus turning the Labour party's dishonest weapon into a boomerang.

- Diary entry (2 August 1935), quoted in Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy. 1933-1940 (1975), p. 92

- There is no use for us to shut our eyes to realities. The fact remains that the policy of collective security based on sanctions has been tried out, as indeed we were bound to try it out unless we were prepared to repudiate our obligations and say, without having tried it, that the whole system of the League and the Covenant was a sham and a fraud. That policy has been tried out and it has failed to prevent war, failed to stop war, failed to save the victim of the aggression.

- Speech to the 1900 Club at Grosvenor House, London, on the Italo-Abyssinian War (10 June 1936), quoted in The Times (11 June 1936), p. 10

- There are some people who do not desire to draw any conclusions at all. I see, for instance, the other day that the president of the League of Nations Union issued a circular to its members in which he...urged them to commence a campaign of pressure upon members of Parliament and members of the Government with the idea that if we were to pursue the policy of sanctions and even to intensify it, it was still possible to preserve the independence of Abyssinia. That seems to me the very midsummer of madness.

- Speech to the 1900 Club at Grosvenor House, London, on the Italo-Abyssinian War (10 June 1936), quoted in The Times (11 June 1936), p. 10

- Is it not apparent that the policy of sanctions involves, I do not say war, but a risk of war? Is it not apparent that that risk must increase in proportion to the effectiveness of the sanctions and also by reason of the incompleteness of the League? Is it not also apparent from what has happened that in the presence of such a risk nations cannot be relied upon to proceed to the last extremity of war unless their vital interests are threatened?

- Speech to the 1900 Club at Grosvenor House, London, on the Italo-Abyssinian War (10 June 1936), quoted in The Times (11 June 1936), p. 10

Prime Minister

[edit]- I myself was not born a little Conservative. I was brought up as a Liberal, and afterwards as a Liberal Unionist. The fact that I am here, accepted by you Conservatives as your Leader, is to my mind a demonstration of the catholicity of the Conservative Party, of that readiness to cover the widest possible field which has made it this great force in the country and has justified the saying of Disraeli that the Conservative Party was nothing if it was not a National Party.

- Speech in Caxton Hall, London, upon his election as Conservative leader (31 May 1937), quoted in The Times (1 June 1937), p. 18

- It is no part of my creed that everybody ought to have the same income, for that would not guarantee that everybody would be equally happy. Happiness springs from within, not from without, but it may be fostered or starved by external conditions, and in the model state that all of us are striving after we would like to see conditions so framed as to enable its subjects to create happiness for themselves. If we are to achieve those conditions the people must be strong and healthy. If they should fall victim to accident or disease they should have available the best of medical science. They should be able to command an income sufficient to keep themselves and their families at any rate in a minimum standard of comfort. They should have leisure for refreshment and recreation. They should be able to cultivate a taste for beautiful things, whether in nature or in art, and to open their minds to the wisdom that is to be found in books. They should be free from fear of violence or injustice. They should be able to express their thoughts and to satisfy their spiritual and moral needs without hindrance and without persecution.

- Speech in the Albert Hall, London (8 July 1937), quoted in The Times (9 July 1937), p. 18

- [O]ur people see that in the absence of any powerful ally, and until our armaments are completed, we must adjust our foreign policy to our circumstances, and even bear with patience and good humor actions which we should like to treat in very different fashion. I do not myself take too pessimistic a view of the situation. The dictators are too often regarded as though they were entirely inhuman. I believe this idea to be quite erroneous. It is indeed the human side of the dictators that makes them dangerous, but on the other hand, it is the side on which they can be approached with the greatest hope of successful issue.

- Letter to Mrs Morton Prince (16 January 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 324

- We pass no judgment here upon the political systems of other countries, but neither Fascism nor Communism is in harmony with our temperament and creed. We will have nothing to do with either of them here. And yet, whatever differences there may be between us and other nations on that subject, do not forget that we are all members of the human race and subject to the like passions and affections and fears and desires. There must be something in common between us if only we can find it, and perhaps by our very aloofness from the rest of Europe we may have some special part to play as conciliator and mediator. An ancient historian once wrote of the Greeks that they had made gentle the life of the world. I do not know whether in these modern days it is possible for any nation to emulate the example of the Greeks, but I can imagine no nobler ambition for an English statesman than to win the same tribute for his own country.

- Speech in Birmingham Town Hall (8 April 1938), quoted in The Times (9 April 1938), p. 17 and Neville Chamberlain, The Struggle For Peace (1939), p. 177

- There was something else in the example of my father's life which impressed me very deeply when I was a young man, and which has greatly influenced me since I took up a public career. I suppose most people think of him as a great Colonial Secretary and tariff reformer, but before he ever went to the Colonial Office he was a great social reformer, and it was my observance of his deep sympathy with the working classes and his intense desire to better their lot which inspired me with an ambition to do something in my turn to afford better help to the working people and better opportunities for the enjoyment of life.

- Speech in the Albert Hall, London (12 May 1938), quoted in The Times (13 May 1938), p. 11

- The Germans who are bullies by nature are too conscious of their strength and our weakness, and until we are as strong as they are, we shall always be kept in this state of chronic anxiety.

- Letter (May 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 350

- When I think of those four terrible years and I think of the 7,000,000 of young men who were cut off in their prime, the 13,000,000 who were maimed and mutilated, the misery and the suffering of the mothers and the fathers, the sons and the daughters, and the relatives and the friends of those who were killed, and the wounded, then I am bound to say again what I have said before, and what I say now, not only to you but to all the world—in war, whichever side may call itself the victor, there are no winners, but all are losers. It is those thoughts which have made me feel that it was my prime duty to strain every nerve to avoid a repetition of the Great War in Europe.

- Speech in Kettering (2 July 1938), quoted in The Times (4 July 1938), p. 21

- [I]s it not positively horrible to think that the fate of hundreds of millions depends on one man, and he is half mad?

- Letter to his sisters (3 September 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 357

- In spite of the harshness and ruthlessness I thought I saw in his face, I got the impression that here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word.

- Letter to Ida Chamberlain after his meeting with Adolf Hitler at Berchtesgaden (19 September 1938), quoted in Ian Kershaw, Hitler, 1936–45: Nemesis (2001), p. 112

- In his view Herr Hitler had certain standards... Herr Hitler had a narrow mind and was violently prejudiced on certain subjects but he would not deliberately deceive a man whom he respected and with whom he had been in negotiation, and he was sure that Herr Hitler now felt some respect for him. When Herr Hitler announced that he meant to do something it was certain that he would do it.

- Remarks to the Cabinet on his meeting with Hitler at Bad Godesberg (24 September 1938), quoted in Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (1972), p. 535

- He thought that he had now established an influence over Herr Hitler, and that the latter trusted him and was willing to work with him. If this was so, it was a wonderful opportunity to put an end to the horrible nightmare of the present armament race. That seemed to him to be the big thing in the present issue.

- Remarks to the Cabinet on his meeting with Hitler at Bad Godesberg (24 September 1938), quoted in Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (1972), p. 538

- That morning he had flown up the river over London. He had imagined a German bomber flying the same course. He had asked himself what degree of protection we could afford to the thousands of homes which he had seen stretched out before him, and he had felt that we were in no position to justify waging a war to-day in order to prevent a war hereafter.

- Remarks to the Cabinet on his meeting with Hitler at Bad Godesberg (24 September 1938), quoted in Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (1972), p. 538

- How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing. It seems still more impossible that a quarrel which has already been settled in principle should be the subject of war.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in The Times (28 September 1938), p. 10

- Referring to the Czechoslovakia crisis

- You know already that I have done all that one man can do to compose this quarrel. After my visits to Germany I have realized vividly how Herr Hitler feels that he must champion other Germans, and his indignation that grievances have not been met before this. He told me privately, and last night he repeated publicly, that after this Sudeten German question is settled, that is the end of Germany's territorial claims in Europe.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in The Times (28 September 1938), p. 10

- I shall not give up the the hope of a peaceful solution, or abandon my efforts for peace, as long as any chance for peace remains. I would not hesitate to pay even a third visit to Germany, if I thought it would do any good.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in The Times (28 September 1938), p. 10

- However much we may sympathize with a small nation confronted by a big and powerful neighbour, we cannot in all circumstances undertake to involve the whole British Empire in war simply on her account. If we have to fight it must be on larger issues than that.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in The Times (28 September 1938), p. 10

- I am myself a man of peace to the depths of my soul. Armed conflict between nations is a nightmare to me; but if I were convinced that any nation had made up its mind to dominate the world by fear of its force, I should feel that it must be resisted. Under such a domination, life for people who believe in liberty would not be worth living: but war is a fearful thing, and we must be very clear, before we embark on it, that it is really the great issues that are at stake.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 372

- For the present I ask you to await as calmly as you can the events of the next few days. As long as war has not begun, there is always hope that it may be prevented, and you know that I am going to work for peace to the last moment. Good night.

- Broadcast (27 September 1938), quoted in The Times (28 September 1938), p. 10

- After reading your letter I feel certain that you can get all essentials without war, and without delay. I am ready to come to Berlin myself at once to discuss arrangements for transfer with you and representatives of the Czech government, together with representatives of France and Italy if you desire. I feel convinced that we could reach agreement in a week. However much you distrust the Prague government's intentions, you cannot doubt the power of the British and French governments to see that the promises are carried out fairly and fully and forthwith. As you know, I have stated publicly that we are prepared to undertake that they shall be so carried out. I cannot believe that you will take the responsibility of starting a world war, which may end civilization, for the sake of a few days' delay in settling this long-standing problem.

- Letter to Hitler (27 September 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 372

- Mussolini...hoped Herr Hitler would see his way to postpone action [against Czechoslovakia] which the Chancellor had told Sir Horace Wilson was to be taken at 2 p.m. to-day for at least 24 hours so as to allow Signor Mussolini time to re-examine the situation and endeavour to find a peaceful settlement. In response, Herr Hitler has agreed to postpone mobilisation for 24 hours. Whatever views hon. Members may have had about Signor Mussolini in the past, I believe that everyone will welcome his gesture of being willing to work with us for peace in Europe. That is not all. I have something further to say to the House yet. I have now been informed by Herr Hitler that he invites me to meet him at Munich to-morrow morning. He has also invited Signor Mussolini and M. Daladier. Signor Mussolini has accepted and I have no doubt M. Daladier will also accept. I need not say what my answer will be. [An HON. MEMBER: "Thank God for the Prime Minister!"] We are all patriots, and there can be no hon. Member of this House who did not feel his heart leap that the crisis has been once more postponed to give us once more an opportunity to try what reason and good will and discussion will do to settle a problem which is already within sight of settlement. Mr. Speaker, I cannot say any more. I am sure that the House will be ready to release me now to go and see what I can make of this last effort. Perhaps they may think it will be well, in view of this new development, that this Debate shall stand adjourned for a few days, when perhaps we may meet in happier circumstances.

- Speech in the House of Commons (28 September 1938). Chamberlain received Hitler's invitation to Munich as he was ending his speech.

- When I was a little boy I used to repeat: "If at first you don't succeed, try, try, try again." That is what I am doing. When I come back I hope I may be able to say, as Hotspur said in Henry IV, "Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety."

- Speech at Heston Airport before his flight to Munich to meet Hitler (29 September 1938), quoted in The Times (30 September 1938), p. 12

- This morning I had another talk with the German Chancellor, Herr Hitler, and here is the paper which bears his name upon it as well as mine.... We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.

- Speech at Heston Airport after his return from Munich (30 September 1938), quoted in The Times (1 October 1938) Oxford Book of Modern Quotes(pdf)

- My good friends, this is the second time in our history that there has come back from Germany to Downing Street peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.

- Excerpt from Chamberlain's speech from the window of 10 Downing Street after returning from Munich (30 September 1938), having signed a peace treaty with Adolf Hitler in Munich, Germany. This remark came back to haunt Chamberlain in 1939 as it rapidly became obvious that Germany would soon be starting another world war; many Britons held Chamberlain personally responsible, and scathing criticism from the public and Parliament drove Chamberlain to resign as Prime Minister on 10 May 1940. As quoted in The Times (1 October 1938), p. 14; cf. Benjamin Disraeli's return from the Congress of Berlin in 1878.

- I am sure that some day the Czechs will see that what we did was to save them for a happier future. And I sincerely believe that what we have at last opened the way to that general appeasement which alone can save the world from chaos.

- Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang (2 October 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 375

- For a long period now we have been engaged in this country in a great programme of rearmament, which is daily increasing in pace and in volume. Let no one think that because we have signed this agreement between these four Powers at Munich we can afford to relax our efforts in regard to that programme at this moment. Disarmament on the part of this country can never be unilateral again. We have tried that once, and we very nearly brought ourselves to disaster. If disarmament is to come it must come by steps, and it must come by the agreement and the active co-operation of other countries. Until we know that we have obtained that co-operation and until we have agreed upon the actual steps to be taken, we here must remain on guard.

- Speech in the House of Commons (3 October 1938)

- A lot of people seem to me to be losing their heads, and talking and thinking as though Munich had made war more, instead of less, imminent.

- Statement (end of October 1938), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 386

- Is this the end of an old adventure, or the beginning of a new; is this the last attack upon a small state or is it to be followed by others; is this in fact a step in the direction of an attempt to dominate the world by force?

- Speech in Birmingham (17 March 1939), quoted in The Times (18 March 1939), p. 14. On 15 March Hitler had occupied Czechoslovakia in contravention of the Munich Agreement.

- I do not think anyone would question my sincerity when I say that there is hardly anything I would not sacrifice for peace, but there is one thing which I must except and that is the liberty which we have enjoyed for hundreds of years and which we will never surrender... No greater mistake could be made than to suppose that, because it believes war to be a senseless and cruel thing, this nation has so lost its fibre that it will not take part to the utmost of its power in resisting such a challenge if it were ever made.

- Speech in Birmingham (17 March 1939), quoted in The Times (18 March 1939), p. 14

- I often think to myself that it's not I but someone else who is P.M. and is the recipient of those continuous marks of respect and affection from the general public who called in Downing Street or at the station to take off their hats and cheer. And then I go back to the House of Commons and listen to the unending stream of abuse of the P.M., his faithlessness, his weakness, his wickedness, his innate sympathy with Fascism and his obstinate hatred of the working classes.

- Letter to Hilda Chamberlain (28 May 1939), quoted in Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy. 1933-1940 (1975), p. 293

- I believe the persecution arose out of two motives: a desire to rob the Jews of their money and a jealously of their superior cleverness. No doubt Jews aren't a lovable people; I don't care about them myself; but that is not sufficient to explain the Pogrom.

- Letter to a sister on the persecution of Jews in Germany (30 July 1939), quoted in Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust: The Jewish Tragedy (1989), p. 81

- I do not propose to say many words tonight. The time has come when action rather than speech is required. Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall upon me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitrament of war. I fear that I may not be able to avoid that responsibility. But, at any rate, I cannot wish for conditions in which such a burden should fall upon me in which I should feel clearer than I do to-day as to where my duty lies... We shall stand at the bar of history knowing that the responsibility for this terrible catastrophe lies on the shoulders of one man—the German Chancellor, who has not hesitated to plunge the world into misery in order to serve his own senseless ambitions.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the British ultimatum to Germany (1 September 1939)

- It now only remains for us to set our teeth and to enter upon this struggle, which we ourselves earnestly endeavoured to avoid, with determination to see it through to the end. We shall enter it with a clear conscience, with the support of the Dominions and the British Empire, and the moral approval of the greater part of the world. We have no quarrel with the German people, except that they allow themselves to be governed by a Nazi Government. As long as that Government exists and pursues the methods it has so persistently followed during the last two years, there will be no peace in Europe. We shall merely pass from one crisis to another, and see one country after another attacked by methods which have now become familiar to us in their sickening technique. We are resolved that these methods must come to an end. If out of the struggle we again re-establish in the world the rules of good faith and the renunciation of force, why, then even the sacrifices that will be entailed upon us will find their fullest justification.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the British ultimatum to Germany (1 September 1939)

- This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note, stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received and that consequently this country is at war with Germany. … It is evil things that we will be fighting against—brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution—and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

- Broadcast from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street (3 September 1939)

- Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established.

- Speech in the House of Commons announcing war with Germany (3 September 1939)

- I simply can't bear to think of those gallant fellows who lost their lives last night in the R.A.F. attack, and of their families who have first been called upon to pay the price. Indeed, I must put such thoughts out of my mind if I am not to be unnerved altogether. But it was just the realisation of these horrible tragedies that has pressed upon me all the time I have been here. I did so hope we were going to escape them, but I sincerely believe that with that madman it was impossible. I pray the struggle may be short, but it can't end as long as Hitler remains in power.

- Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang (5 September 1939), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 419

- To us in Europe life had become absolutely intolerable, and it is to restore the possibility of living any civilised life at all that we have got to put an end to Nazi policy.

- Letter to Lord Tweedsmuir (25 September 1939), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 424

- As you know I have always been more afraid of a peace offer than of an air raid.

- Letter to Ida Chamberlain (8 October 1939), quoted in Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy. 1933-1940 (1975), p. 355

- We have to kill one another just to satisfy that accursed madman. I wish he could burn in Hell for as many years as he is costing lives.

- Statement (15 October 1939), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 419

- I find war more hateful than ever, and I groan in spirit over every life lost and every home blasted.

- Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang (Christmas 1939), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 430

- I stick to the view I have always held that Hitler missed the bus in September 1938. He could have dealt France and ourselves a terrible, perhaps a mortal, blow then. The opportunity will not recur.

- Letter to Hilda Chamberlain (30 December 1939), quoted in Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy. 1933-1940 (1975), p. 355

- I don't agree...that we should make peace with Germany in order to resist Russia. I still regard Germany as Public Enemy No. 1, and I cannot take Russia very seriously as an aggressive force, though no doubt formidable if attacked in her own country. I am afraid that, although the Germans would like to make peace on their own terms, they are very far from that frame of mind which will be necessary before they are prepared to listen to what we should call reason.

- Letter to Sir Francis Lindley (1 January 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), pp. 427-428

- The result was that when war did break out German preparations were far ahead of our own, and it was natural then to expect that the enemy would take advantage of his initial superiority to make an endeavour to overwhelm us and France before we had time to make good our deficiencies. Is it not a very extraordinary thing that no such attempt was made? Whatever may be the reason—whether it was that Hitler thought he might get away with what he had got without fighting for it, or whether it was that after all the preparations were not sufficiently complete—however, one thing is certain: he missed the bus.

- Speech to the Central Council of the National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations at Central Hall, Westminster (4 April 1940), quoted in "Confident of Victory," The Times (5 April 1940), p. 8

- Hitler began the 'Westfeldzug' five weeks later and entered France at the beginning of June. June 10th, Paris was declared to be an 'open town'.

- The most common cry, and this of course is chronic in the U.S.A., is "why are we always too late? why do we let Hitler take the initiative?" ... The answer to these questions is simple enough, but the questioners would rather not believe it. It is, "because we are not yet strong enough". ... We have plenty of man-power, but it is neither trained nor equipped. We are short of many weapons of offence and defence. Above all, we are short of air power. If we could weather this year, I believe we should be able to remove our worst deficiencies.

- Letter (4 May 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 438

Post-Premiership

[edit]- In the afternoon of to-day it was apparent that the essential unity could be secured under another Prime Minister, though not myself. In these circumstances my duty was plain ... For the hour has now come when we are to be put to the test, as the innocent people of Holland, Belgium, and France are being tested already. And you, and I, must rally behind our new leader, and with our united strength, and with unshakable courage, fight and work until this wild beast, that has sprung out of his lair upon us, has been finally disarmed and overthrown.

- Broadcast (10 May 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 441

- We are a solid and united nation, which would rather go down to ruin than admit the domination of the Nazis... If the enemy does try to invade this country, we will fight him in the air and on the sea; we will fight him on the beaches with every weapon we have... We shall be fighting...with the conviction that our cause is the cause of humanity and peace against cruelty and wars; a cause that surely has the blessing of Almighty God.

- Broadcast (30 June 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 449

- Give us another 3 or 4 months of production, not more hampered than it is at present, and we shall have something over, with which we can make ourselves disagreeable in many ways, and many places. We could perhaps take a stronger line with Japan then, even though we still got no help from the U.S.A. ... People ask me how we are going to win this war. I suppose it is a very natural question, but I don't think the time has come to answer it. We must just go on fighting as hard as we can, in the belief that some time—perhaps sooner than we think—the other side will crack.

- Letter to his sister (14 July 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 449

- It is not inconceivable that human civilisation should be permanently overcome by such evil men and evil things, and I feel proud that the British Empire, though left to fight alone, still stands across their path, unconquered and unconquerable.

- Last broadcast (11 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 454

- I will confess to you that never for one moment have I had any doubt that I had to do what I did, and when I look back I don't see what more I could have done, having regard to the state of public opinion and the sharpness of party feeling. That is a tremendous solace to me. Few men can have known such a reversal of fortune in so short a time.

- Letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang (14 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 455

- Never for one single moment have I doubted the rightness of what I did at Munich, nor can I believe that it was possible for me to do more than I did to prepare the country for war after Munich, given the violent & persistent opposition I had to fight against all the time.

- Letter to Stanley Baldwin (17 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 456

Quotes about Chamberlain

[edit]- Alphabetised by author

- You have sat here too long for any good you are doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!

- Leo Amery, concluding his speech in the "Norway debate" (7-8 May 1940), in the British Parliament's House of Commons. In saying these words, he was echoing what Oliver Cromwell had said as he dissolved the Long Parliament in 1653. As quoted in Neville Chamberlain: A Biography by Robert Self (2006), p. 423

- Neville annoys me by mouthing the arguments of complete pacifism while piling up armaments.

- Clement Attlee in a letter to Tom Attlee (22 February 1939), quoted in Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Hitler. British Politics and British Policy. 1933-1940 (1975), p. 177

- He was Lord President [in Churchill's government]. Very able and crafty, and free from any rancour he might well have felt against us. He worked very hard and well: a good chairman, a good committee man, always very businesslike. You could work with him.

- Clement Attlee, quoted in Francis Williams, A Prime Minister Remembers: The War and Post-War Memoirs of The Rt Hon. Earl Attlee (1961), p. 37

- We were convinced that a major war was in the offing, what with the uncorrelated news before us of Schuschnigg's arrest by the Nazis, the fall of the French cabinet, Blum's formation of a new one, the mobilization of French troops on the border and the clamor of the British population for the resignation of Neville Chamberlain, who continued to place the interests of his class above the interests of his country.

- Alvah Bessie, Men in Battle: A Story of American in Spain (1939), p. 72

- Neville Chamberlain’s government, like most of the British population, was still prepared to live with a rearmed and revived Germany. Many conservatives saw the Nazis as a bulwark against Bolshevism. Chamberlain, a former lord mayor of Birmingham of old-fashioned rectitude, made the great mistake of expecting other statesmen to share similar values and a horror of war. He had been a highly skilled minister and a very effective chancellor of the Exchequer, but he knew nothing of foreign policy or defence matters. With his wing-collar, Edwardian moustache and rolled umbrella, he proved to be totally out of his depth when confronted by the gleaming ruthlessness of the Nazi regime.

- Antony Beevor The Second World War (2016), p. 19

- I think one of the fascinating things about Chamberlain was that he tried to do the right thing by the country and all the way through these speeches [in The Struggle for Peace] actually, some of which I know, you can see how he is in a sense wrestling with the fact that however evil Hitler is the thought of war is just so horrific.

- Tony Blair, interview with Simon Schama for Simon Schama's Tour of Downing Street. Part 2: The Cabinet Room (2007), at 3:19

- The debate over appeasement – the attempt by Britain and France to avoid war by making "reasonable" concessions to German and Italian grievances during the 1930s – is as enduring as it is contentious. Condemned, on the one hand, as a "moral and material disaster", responsible for the deadliest conflict in history, it has also been described as "a noble idea, rooted in Christianity, courage and common-sense". Between these two polarities lies a mass of nuance, sub-arguments and historical skirmishes. History is rarely clear-cut, and yet the so-called lessons of the period have been invoked by politicians and pundits, particularly in Britain and the United States, to justify a range of foreign interventions – in Korea, Suez, Cuba, Vietnam, the Falklands, Kosovo and Iraq (twice) – while, conversely, any attempt to reach an accord with a former antagonist is invariably compared with the infamous 1938 Munich Agreement. When I began researching this book, in the spring of 2016, the spectre of Neville Chamberlain was being invoked by American conservatives as part of their campaign against President Obama's nuclear deal with Iran, while today the concept of appeasement is gaining new currency as the West struggles to respond to Russian revanchism and aggression. A fresh consideration of this policy as it was originally conceived and executed feels, therefore, timely as well as justified.

- Tim Bouverie Appeasing Hitler (2020)

- Hitler's open atrocities against the Jews in the autumn of 1938 certainly deeply impressed Chamberlain... And of course Halifax was certainly no less shocked. Many people who did not know Chamberlain personally had the impression that he was a gullible and obstinate old man. During all that ghastly time I saw almost as much of him as I did of Halifax and I will say, from my observation of him, that nothing could be further from the truth. He was haunted day and night by the prospect that he saw clearly enough, he gave everything of his strength to try to avert it. Many people thought he was a cynic. Cynicism was a virtue with which he was perhaps not sufficiently equipped, or he would not have been taken in by Hitler's rather transparent "piece of paper". On the other hand he had quite a streak of the sentimental and emotional in him, which betrayed him into uttering those unguarded words to the crowd in Downing Street after his return from Germany.

- Alexander Cadogan, statement (1963), quoted in The Diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan O.M., 1938–1945, ed. David Dilks (1971), p. 132

- During these long violent months of war we had come closer together than at any time in our twenty years of friendly relationship amid the ups and downs of politics. I greatly admired his fortitude and firmness of spirit. I felt when I served under him that he would never give in: and I knew when our positions were reversed that I could count upon the aid of a loyal and unflinching comrade.

- Winston Churchill to Mrs. Chamberlain (11 November 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 457

- It fell to Neville Chamberlain in one of the supreme crises of the world to be contradicted by events, to be disappointed in his hopes, and to be deceived and cheated by a wicked man. But what were these hopes in which he was disappointed? What were these wishes in which he was frustrated? What was that faith that was abused? They were surely among the most noble and benevolent instincts of the human heart-the love of peace, the toil for peace, the strife for peace, the pursuit of peace, even at great peril, and certainly to the utter disdain of popularity or clamour.

- Winston Churchill, Speech to House of Commons on 12 November 1940, 3 days after his death.

- [In September 1938] I asked Chamberlain straight out, did he really believe that Hitler wanted a peaceful settlement? The Prime Minister paused before replying and then said reflectively: "If we accept the challenge now it means war. If we delay a decision something might happen. Hitler may die." Morrison, Dalton, and I looked at one another but said nothing.

- Walter Citrine, Men and Work: An Autobiography (1964), p. 365

- This was one of the frankest interviews I had attended, but my experience of Chamberlain had shown him to be far more forthcoming in private conversation than most of his predecessors. He was not liked by my colleagues, and my own first impressions were similar to theirs, with the major difference that I was considerably impressed by the incisiveness of his mind and the clarity of his speech. He always knew his case, but I felt that he showed little generosity in his attitude to anyone whom he felt was a political opponent. He was an adept at veiled sarcasm when he replied to trade union people ... I remember one occasion when he was tearing up some argument which we had presented, Ben Tillett interposing mildly: "Don't be sarcastic. You can put your case without that." Chamberlain seemed rather taken aback, and as far as I could judge, he tried to follow Ben's advice. He appeared at that time to be utterly devoid of human sentiment. Like Poo Bah in the Mikado, he seemed to have been born sneering.

- Walter Citrine, Men and Work: An Autobiography (1964), pp. 366-367

- I can never erase from my mind the thought of his struggle, in the later days of his life, against the depression resulting from his political misfortunes and knowing that he was suffering from an incurable illness. Knowing also that, despite his long public service, few of those who cheered him so loudly on his return from Munich really cared what happened to him.

- Walter Citrine, Men and Work: An Autobiography (1964), p. 368

- The Prime Minister then told us the story of his visit to Bechtesgaden. Looking back upon what he said, the curious thing seems to me now to have been that he recounted his experiences with some satisfaction. Although he said that at first sight Hitler struck him as "the commonest dog" he had ever seen, without one sign of distinction, nevertheless he was obviously pleased at the reports he had subsequently received of the good impression that he himself had made. He told us with obvious satisfaction how Hitler had said to someone that he had felt that he, Chamberlain, was "a man." But the bare facts of the interview were frightful...

After ranting and raving at him, Hitler had talked about self-determination and asked the Prime Minister whether he accepted the principle. The Prime Minister had replied that he must consult his colleagues. From the beginning to end Hitler had not shown the slightest sign of yielding on a single point. The Prime Minister seemed to expect us all to accept that principle without further discussion because time was getting on.- Duff Cooper, diary entry (17 September 1938), quoted in Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953), pp. 229-230

- Personally I believe that Hitler has cast a spell over Neville. After all, Hitler's achievement is not due to his intellectual attainments nor to his oratorical powers, but to the extraordinary influence which he seems able to exercise over his fellow-creatures. I believe that Neville is under that influence at the present time. "It all depends," he said, "on whether we can trust Hitler."

"Trust him for what?" I asked. "He has got everything he wants for the present and he has given no promises for the future."

Neville also said that he had been told, and he believed, that he himself had made a very favourable impression on Hitler, and that he believed he might be able to exercise a useful influence over him.- Duff Cooper, diary entry (24 September 1938), quoted in Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953), p. 235

- At 8 p.m. we listened to the Prime Minister's broadcast... It was a most depressing uterrance. There was no mention of France in it or a word of sympathy for Czecho-Slovakia. The only sympathy expressed was for Hitler, whose feeling about the Sudetens the Prime Minister said that he could well understand, and he never said a word about the mobilisation of the Fleet. I was furious. Winston rang me up. He was also most indignant and said that the tone of the speech showed plainly that we're preparing to scuttle.

- Duff Cooper, diary entry (27 September 1938), quoted in Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953), pp. 238-239

- Neville Chamberlain was determined to go to extreme lengths in the cause of peace ... That was why he flew to Germany ... I may recall that after thirty years in Parliament I never saw a House of Commons so unanimous in its apparent goodwill to a national leader and never before did Socialist Members of Parliament open their hearts so fully to a traditional opponent such as myself. At least five of them told me spontaneously how fine they thought Chamberlain's action, and one of them, a famous extremist from the North, rushed up to me with tears streaming down his cheeks, put his hand on my shoulder and exclaimed, "Isn't it marvellous how God has found a man to save us from all the misery of war?"

- Lord Croft, My Life of Strife (1948), p. 287

- Very shortly after his return from Munich Neville Chamberlain asked me to lunch quietly at No. 10. I put the question straight to him: "What really is your impression of Hitler?" He answered that he "believed that no man, much less the accepted leader of a great nation, could have sworn to me his will for peace unless he meant it. Hitler's words rang absolutely sincerely, never from anyone have I had assurances so emphatic." I immediately asked the Prime Minister: "Then why...did you start the very day after your return to do everything possible to speed armaments all round?" He answered, that although he believed Hitler he had felt that he was "in the presence of a man of intense cruelty and I was obsessed with the fact that if in a year or two he changed his mind he would be so ruthless that he would stop at nothing."

- Lord Croft, My Life of Strife (1948), p. 289

- What a Chamberlain government would have done had there been no war in 1939 will never be known, but an election was due in 1940, and the manifesto proposals outlined by the Conservative Research Department embraced family allowances and the inclusion of insured persons' dependants in health cover—about half the advances usually attributed to Beveridge. As Lady Cecily Debenham wrote to Chamberlain's widow, Anne, after his death: "Neville was a Radical to the end of his days. It makes my blood boil when I see his ‘Tory’ and ‘Reactionary’ outlook taken as a matter of course because the Whirligig of Politics made him leader of the Tory party."

- Andrew J. Crozier, ‘Chamberlain, (Arthur) Neville (1869–1940)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2011, accessed 19 April 2013.

- I would like to testify that you did more than any former British Statesman to make a true friendship between the peoples of our two countries possible, and, if the task has not been completed, that it has not been for want of goodwill on your part. I hope that you may still be able to work for, and that we may both be spared to see, the realisation of our dreams,—to see our two peoples living side by side with a deep neighbourly sense of their value one to another, and with a friendship which will make possible whole-hearted co-operation between them in all matters of common interest.

- Eamon de Valera to Chamberlain (15 May 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 311

- All those months of acute anxiety that heralded and followed the French collapse while I was at the War Office, Neville was so unvaryingly sympathetic and helpful, that I feel I could never thank him enough for all he did. His faith in final victory never wavered at the darkest hour; I am confident that he will still share with us the happier days that must come.

- Anthony Eden to Mrs. Chamberlain (16 November 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 466

- Few men had a more real enjoyment of all things of beauty and art, whether in the world of nature or of men, which make life colourful and rich, and few had his knowledge and deep appreciation of all that is greatest in music. No one was a truer lover of the countryside. He shared with Lord Grey the love of birds, and like him had learnt as a fisherman the art of patience, so essential to the trade of politics. Anyone who worked with him, and I suppose I worked as closely with him as anybody, was bound to be impressed by two things. One was his complete disinterestedness and disregard of any lesser thoughts of self; and the other his unfaltering courage and tenacity, once he had made up his mind that a thing was right. These are qualities of signal value for a democratic leader, and all who have the vision to appreciate how close they lie to the roots of health in a democratic state will feel a debt to Neville Chamberlain for his practical demonstration of them.

- Lord Halifax, Fulness of Days (1957), p. 231

- No man could have done more to save the world from this war. Your efforts to secure peace gave to our cause a moral strength that can never be disregarded. For this all who have regard for Britain's honour must be profoundly grateful. You have saved us from a war at a moment when we were unready, and if others had been sincere and faithful to their pledges would have prevented hostilities in Europe perhaps for generations. You will surely receive the reward of those who are promised the blessing of peace-makers.

- Cardinal Hinsley to Chamberlain (5 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 462

- If ever that silly old man comes interfering here again with his umbrella, I'll kick him downstairs and jump on his stomach in front of the photographers.

- Adolf Hitler after the Munich Agreement, quoted in Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, The Inner Circle (1959), p. 135

- What calibre of Conservatism Chamberlain would have sought to impose is open to conjecture, since he never properly had an opportunity to impose one. He was kept cramped in the wings for so long that he reached the centre stage only moments before the intermission. Yet there is a strong impression that he would have tried to impose something: his politics was a doctrine of action because that was the sphere where he knew himself to be at his best and because that was what he thought he was there to do. It is far from clear, on the other hand, in which direction he would have gone. His own introduction of tariffs in 1932, with suitable acknowledgement to "name and blood", had blocked one path. It may be that he would have extended the moderate collectivism towards which Conservatism, in its "national" guise, had been moving; certainly he took pains to rebut the charge that the National Government was a sterile administration. His view that British government in the 1930s was reformist may have been heartfelt for his achievement, as much as his propaganda, suggests that he pursued a measure of social reform as an end in itself. To that extent the European imbroglio to which Chamberlain was heir has masked the degree to which he was a radical democrat. He was closer to a compassionate understanding of "the people" than any other leader examined here. He understood the urban poor, as Baldwin did not, and he had the organizational equipment to direct those who agreed with him.

- Andrew Jones and Michael Bentley, 'Salisbury and Baldwin', in Maurice Cowling (ed.), Conservative Essays (1978), p. 37

- My reliable informants in the German camp had already made it clear to me that Hitler regarded the Prime Minister [Neville Chamberlain] as an impertinent busybody who spoke the ridiculous jargon of an out-moded democracy. The umbrella, which to the ordinary German was the symbol of peace, was in Hitler's view only a subject of derision.

- Ivone Kirkpatrick, The Inner Circle (1959), p. 122

- I was never able to discover what passed through Mr. Chamberlain's mind in this fleeting negotiation which he conducted entirely alone without, so far as I am aware, warning anyone in advance. Did he believe in Hitler's sincerity? Or was he carried away by the emotion of relief that war had been averted? Or did he believe that the best chance with Hitler was to try to bind him by a public declaration and then to proclaim the belief that Hitler would keep his word? I am inclined to think that the last is the most likely hypothesis. One thing is certain. The subsequent seizure of Prague was a bitter blow to Mr. Chamberlain, which provoked a personal resentment against Hitler. I noticed that whenever Hitler's name was mentioned after March 17th [1939], the Prime Minister looked as if he had swallowed a bad oyster.

- Ivone Kirkpatrick, The Inner Circle (1959), pp. 130-131

- I cannot but add that I have always been a supporter and defender of your policy when you were Prime Minister. I am sure that it was right. In view of the attitude of France and of the unreadiness of this country for which you were in no way to be blamed, it would have been folly to precipitate then a war with Germany. It was your strength of will and purpose and self-restraint that saved us from that mistake. When the time to meet the challenge of Hitler came, you had made it plain to the whole impartial world that you had done everything possible to keep Europe from war, and to fix the blame for that calamity on the unbridled ambition of Hitler. You enabled your country to enter the war with a clear conscience and a united will.

- Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang to Chamberlain (6 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), pp. 462-463

- A vein of self-sufficient obstinacy in the new Minister contributed to the difficulties that baffled all our endeavours ... The machinery which Mr. Chamberlain created showed itself incompetent to deal even with volunteer recruits, and certainly too unreliable to be entrusted with the administration of dictatorial powers ... Mr. Neville Chamberlain is a man of rigid competency. Such men have their uses in conventional times or in conventional positions, and are indispensable for filling subordinate posts at all times. But they are lost in an emergency or in creative tasks at any time.

- David Lloyd George on Chamberlain's role as Director of National Service, War Memoirs, Volume I (1938), p. 811

- Mr Chamberlain views everything through the wrong end of a municipal drain-pipe.

- David Lloyd George, as quoted in Rats! (1941) by "The Pied Piper", p. 108; similar remarks have also been attributed to Winston Churchill in later works, including Neville Chamberlain : A Biography (2006) by Robert C. Self, p. 12

- [T]he Parliament of 1924–9 was a great constructive Parliament. It marked some of the greatest advances in social and administrative reforms that have ever been made. For these, Baldwin relied on Neville Chamberlain and on Churchill... [Chamberlain] moved firmly along a clearly marked course. He was associated, above all, with the Widows, Orphans and Old Age Pensions Act—one of the foundations of the modern Welfare State—and with the great reforms of local government... Neville Chamberlain in this Parliament, as in previous ones, proved himself a true successor to the reforming tradition of England. Some of his ideas went back to those of Disraeli; others to the unauthorised programme of his great father, Joseph Chamberlain. Others followed naturally on the work of social reform which made the Liberal Governments of 1906 onwards so outstanding. His heart was in all this work, which he thoroughly understood. But he did not wear his heart upon his sleeve; on the contrary, he kept it so closely buttoned up behind his formal morning-coat that he was not suspected of anything except a desire for efficiency. In fact, he was inspired by a deep sentiment and feeling for the poor and suffering. Neither the Opposition who disliked him, nor those of our party who admired him, could see behind the mask. Yet in this Parliament he stood out. If Baldwin was by nature indolent, Neville Chamberlain was the most hard-working of men. The troubles of later years should never be allowed to obscure the great achievements of this period.

- Harold Macmillan, Winds of Change, 1914–1939 (1966), pp. 172-174

- Chamberlain was not a favourite of the House, and he never obtained that attention from the Opposition which it is necessary for a leading Minister to secure. This was a defect partly of manner and partly of feeling. He had a certain intellectual contempt for people whose views he thought ridiculous; and most of the Labour Party he put into that category. But he was not able to conceal this, and his tone revealed a degree of sarcasm and even rudeness towards his opponents, which is contrary to the true House of Commons tradition, at least at the top. Hard blows can be taken and given in our Parliamentary system. They are not long remembered. But superciliousness and arrogance are much more wounding. Nevertheless, he was a commanding personality. His speeches were admirably prepared and argued. If his voice was rasping and often weak, his Parliamentary style was good. He marshalled facts and statistics with ease. His slim figure, conventionally dressed (he usually wore a tail coat and stiff wing-collar), his well-groomed appearance, his corvine physiognomy, his perfect self-control: all these made him an outstanding Parliamentarian. I can still see him standing at the box, erect and confident. But he was respected and feared, rather than loved, except by the few who were his intimates and knew the kindliness that lay behind his bleak exterior.

- Harold Macmillan, Winds of Change, 1914–1939 (1966), pp. 313-314

- Although one of the Opposition, I feel I must say how much your presence in the House is missed by me. However profoundly I may have felt disagreement with you over foreign policy at times, I could not take less account of several splendid things you did during the short time it has been my privilege to share the same historic floor with you. I recall how you stood firm over Members' pensions, your moving tribute to George Lansbury, your greatness in making room for Winston Churchill and then facing the same House by his side. I would like to have understood you better; public criticism can be so unfair to a sincere man. I can only assure you of my deep respect, and continuous thought for you in such a disappointing moment as this.

- Labour MP John Morgan to Chamberlain (c. 16 October 1940), quoted in Keith Feiling, Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 464

- These men are not made of the same stuff as the Francis Drakes and the other magnificent adventurers who created the empire. These, after all, are the tired sons of a long line of rich men, and they will lose their empire.

- Benito Mussolini, remarks to Count Ciano after meeting Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax (11 January 1939), quoted in Malcolm Muggeridge (ed.), Ciano's Diary, 1939–1943 (1947), pp. 9–10

- That, too, was what Neville Chamberlain was clearly doing in London from 1937 until the gray morning of 1941 when his cancer finally killed him. During those fateful years he too was "sparring with the situation," seeking an easy way out. He has been accused round the world of being a foolish old man who did not understand what it would take to defend his country against the Nazis. That, I am sure, is a fundamental error. He knew full well the number of planes and tanks it would take, but he could not bring himself to the hard decision of ordering the industrial and economic revolution that was necessary to produce them.

- James Reston, Prelude to Victory (1942), p. 21-22

- We, like the the British and French, improvised and compromised, and these two words, I am convinced, are the patents of "too little and too late." All this is relevant to our present situation because once a nation or the leaders of a nation get into the habit of substituting palliatives for cures, once they refuse to face the facts and deal with them directly and courageously, their capacity for self-deception is unlimited. Neville Chamberlain was tragic proof of this point. When he came back from Munich, waving Adolf Hitler's signature on a no-war scrap of paper and announcing "peace in our time," he gradually convinced himself that what he wanted to believe was true, and so he became so convinced of it that on March 9, 1939, he sent a note up to the press gallery in the House of Commons telling the reporters that he would like to see them that afternoon at four o'clock. When the reporters arrived for this unexpected conference, they found him beaming, which was unusual. He said he had called this meeting because he was convinced at last that there was now real hope of a European settlement. He explained his feeling at full length and finished by talking not only of better Anglo-German relations but of European disarmament. Now, Neville Chamberlain may have been a misguided statesman, but he was an honest man, and while the Foreign Office was visibly astounded by his remarks, we sent them out to the world that same afternoon. Six days later, the German Army marched into Prague.

- James Reston, Prelude to Victory (1942), p. 22-23

- Afterward Strang, like many in the Foreign Office, described Munich frankly as a “débâcle.” And there is no doubt that Chamberlain’s personal diplomacy looks profoundly amateurish by the standards of later summits. No psychological profiles of his opponent had been prepared; there was no sign of what would now be called “position papers” or “briefing books.” The prime minister kept professional diplomats at arm’s length, including his foreign secretary, and went to Berchtesgaden without even his own interpreter and record keeper. He did not think through his bottom line and tended to throw away bargaining chips without gaining anything in return. But Chamberlain’s basic problem was not one of method but of assumptions. He flew to Berchtesgaden because he feared that the fate of Europe was in the hands of a madman; he came back with the illusion that he was forging a personal relationship with Hitler and that this would bear fruit because, at root, the Führer was a man of his word. More dangerous still was the idealism (and hubris) of a politician who believed he could bring peace to Europe and, perhaps, the ambition of a marginalized younger son determined to outdo his father and his brother. But none of this would have mattered if Chamberlain and most of his colleagues had not convinced themselves that war over Czechoslovakia would mean the devastation of much of London. Not for the last time a British prime minister got it profoundly wrong about weapons of mass destruction.

- David Reynolds, Summits: Six Meetings that Changed the Twentieth Century (2007), pp. 97-98

- In short, Hitler was a much more effective negotiator than Chamberlain, but he never wanted to negotiate, whereas Chamberlain, a less skilled tactician, got what he really wanted—peace not war. Yet it was a hollow victory, because Hitler never intended to honor the Munich agreements. He was soon kicking himself for losing his nerve at the end of September. In March 1939, when he seized the rest of Czechoslovakia, he was not only going beyond his professed aim of simply bringing Germans within the Reich, he had also torn up what had been signed at Munich. A disenchanted Chamberlain was forced into a complete U-turn, offering guarantees to Poland, Romania and other countries possibly on the Nazi hit-list in a belated and panicky effort to deter further German expansion. That summer Chamberlain still hoped for peace but Hitler was now bent on having a war over Poland, determined not back down a second time. He felt he had the measure of his opponents. “Our enemies are small worms,” he told his generals in August 1939. “I saw them in Munich."

- David Reynolds, Summits: Six Meetings that Changed the Twentieth Century (2007), pp. 99-100

- [H]e was later one of the most successful Departmental Ministers of his time. The Ministry of Health probably regards him as the best Minister assigned to it since its creation; the Treasury as perhaps the most competent Chancellor for the current business of the Department, and within the limits of orthodox policy, since Gladstone. He has all the qualities that Whitehall most desires for its normal tasks: industry, order, precision, correctitude, decision. He is neither wayward, nor fickle, nor fanciful. He is a lucid expositor, a competent defender, of departmental policy.

- Arthur Salter, Security: Can We Retrieve It? (1939), p. 284

- Spare, even ascetic, in figure, dark-haired and dark-eyed; with a profile rather corvine than aquiline; he carries his seventy years well and looks and seems less than his age. His voice has a quality of harshness, with an occasional rasp, and is without music or seductive charm, but it is clear and resonant and a serviceable instrument of his purpose. In debate and exposition his speech is lucid, competent, cogent, never rising to oratory, unadorned with fancy, and rarely touched by perceptible emotion. But it gives a sense of mastery of what it attempts, well reflects the orderly mind behind and, if something is lost, it derives strength from its disregard of all that is not directly relevant to the close-knit argument of his theme. In manner he is glacial rather than genial.

- Arthur Salter, Security: Can We Retrieve It? (1939), p. 285

- If we wish to find the closest analogy, among statesmen of the first rank, we must turn to one of a different nation who pursued a very different, and in foreign affairs even a diametrically opposite, policy. Monsieur Poincaré, too, had a restricted range of habitual vision, and an unequalled clarity of vision within that range; what he saw, he saw precisely in all its detail; what he did not so see was altogether outside his consciousness; he had a complete mastery of all he knew, and a supreme disregard for what he did not. He was glacial and unresponsive. He had a coldly, frictionlessly functioning brain, which was a perfect instrument for his limited, inflexible purposes. The force of a strong nature, the determination of a strong will, the vigour of a robust physique, were all increased by this concentration of effort and interest. Mr. Chamberlain had all these characteristics, though all of them in a less extreme form; he is compact, cold, correct, concentrated, with both the limitations and the strength which these qualities involve. The analogy is confirmed by the similarity of the personal reactions of the Celt of genius to the Lorrainer and to the Midland Englishman.

- Arthur Salter, Security: Can We Retrieve It? (1939), p. 288

- He cares more where he cares most, because he cares less where he cares least. His will is stronger for his central purpose, because he confines it to that purpose. His strength is the strength of concentration.

And this must be the central note of any personal description. We may regret the limitation of vision, the inability to gather strength or support by setting policy on a wide and generous basis, the failure to conciliate and attract those of different outlook and ideas, the inconvenient clarity of his exposition of those features of his policy which most annoy his critics or his potential allies, the undisguised expression of his dislikes and prejudices, the inadequate comprehension of the mental attitude of many whose reactions to his declarations are of great importance. But the personal force remains, the greater for its direct purpose because it is concentrated, not dispersed. He has the defects of his qualities, but he has also the qualities of his defects.- Arthur Salter, Security: Can We Retrieve It? (1939), p. 291

- Being very efficient, Chamberlain had, as he said himself, "no capacity for looking on and seeing other people mismanaging things." Of his planning there is no better example than the programme that he made for the Cabinet in November 1924, for the reform of local government. It was a five-year plan to cover the whole field of health, housing, local taxation and rating, and to be carried out methodically by twenty-five Bills neatly spaced over each succeeding session of the five-year Parliament. No previous Minister of Health or President of the Local Government Board had ever contemplated so ambitious a task. Chamberlain not only convinced a doubtful Cabinet of its advantages, but passed the whole programme through Parliament in little more than four years. Without his remarkable grasp of detail, his achievement would have been impossible. From start to finish it involved an almost interminable series of administrative problems. The result was to display the remarkable talent for administration that had already made his reputation on the Birmingham City Council. The Ministry of Health and the Exchequer provided an unlimited opportunity for still further applying it. His critics sometimes thought that this grasp of detail made him undertake work that ought to have been left to his permanent staff. I am sure, however, that his reforms between 1924 and 1929 would never have been carried through if it had not been for his knowledge of detail and the use that he made of it.

- Viscount Templewood, Nine Troubled Years (1954), pp. 36-37

- A mentality such as his was equally far apart from the easygoing quietism of Baldwin and the introspective hesitations of MacDonald. Although a man of great personal modesty, Chamberlain was not tolerant. His likes and dislikes were even stronger than Baldwin's, so strong, in fact, that they sometimes led him to mistaken decisions, and when he became Prime Minister, to some bad appointments to responsible posts. He had none of Baldwin's appeal to other men's feelings. "I like your old man Baldwin," Lloyd George once said to me. "I could work with him." He could never work with Chamberlain. Whilst it was the humanist's touch that made Labour hang on Baldwin's words, it was the analyst's accuracy that, reacting against Labour's reluctance to face unpleasant facts, made the Trade Union leaders regard Chamberlain as a bitter enemy, when in practice he was a pronounced radical reformer far to the left of many of them and most of his own party.

- Viscount Templewood, Nine Troubled Years (1954), p. 37

- Appeasement did not mean surrender, nor was it a policy only to be used towards the dictators. To Chamberlain it meant the methodical removal of the principal causes of friction in the world. The policy seemed so reasonable that he could not believe even Hitler would repudiate it. Hitler at the time seemed genuinely anxious to live on good terms with the British Empire. He had obtained equality of status for his country, and needed a period of peace to consolidate his political power. When, therefore, at Munich, he signed the pledge of perpetual friendship with Great Britain, he appeared not only to be acting in good faith, but to be embarking on a policy equally advantageous to himself and Germany. These were the considerations that influenced him to think that the Führer was more likely to keep his word than to break it. Supposing, however, that Chamberlain was mistaken, for he never regarded his opinion as infallible, he felt that he could fall back on the re-insurance policy that he possessed in the programme of British rearmament. The ink, indeed, was scarcely dry on the agreement when...he met the Service Ministers and Chiefs of Staff and agreed with them on a series of measures for accelerating rearmament, particularly the air programme of Spitfires and Hurricanes. Although Hitler was enraged at this reaction, Chamberlain none the less persisted with his double programme of peace if possible, and arms for certain. If I described his mind in a sentence, I would say that at the time of Munich he was hopeful but by no means sure that Hitler would keep his word, but that after Prague he came to the conclusion that only a show of greater determination would prevent him from breaking it.

- Viscount Templewood, Nine Troubled Years (1954), p. 374

- The British and German accounts of the conversation agree that he walked warily, and knew that he was dealing with an abnormal fanatic. It may be that his self-confidence misled him into thinking that the Führer could be moved by arguments and explanations that seemed to us unanswerable. British Ministers, whether Grey, Asquith or Baldwin, have always been inclined to think and act as if foreigners thought and acted like themselves. Chamberlain evidently believed that there was at least a small corner of Hitler's mind that was sufficiently like his own to respond to British arguments. The belief was something more than wishful thinking. The plan of the blitzkrieg against Czechoslovakia, for instance, was dropped as the result of Chamberlain's insistence. The truth seems to be that each of them was influenced by the other, but that neither really understood the other's point of view. Chamberlain failed to realise that Hitler wanted the whole continent and not a few million more Germans. Hitler, when he talked of perpetual peace between Germany and Great Britain, always assumed that it would be based upon the division of the old world between them.

- Viscount Templewood, Nine Troubled Years (1954), p. 381

- The mistake that the Führer made was to think that Chamberlain had accepted the Munich terms from weakness. Whatever may be said to the contrary, Chamberlain did not agree because of our military unpreparedness. On the contrary, he sincerely believed that it was necessary in the general interests of world peace to let the Sudeten Germans unite with the Germans of the Reich. The fact that we were military weak took a secondary place in his mind. Extremely obstinate by nature, he would never have submitted to a threat or surrendered through fear. He was prepared to make an agreement only because he felt that it was definitely wrong to plunge Europe into war to maintain what, even in the negotiations of the Versailles Treaty, was regarded as a precarious and vulnerable compromise. When he was told that the loss of the Sudetenland would destroy the balance of power in Europe, his answer was that a balance that depended on Czechoslovakia was no longer reliable when the defences had been turned by Hitler's occupation of Austria. Perhaps he underrated the strength of Czech nationalism. Whilst his mind was insular to the extent that he thought that foreigners thought like us, it was cosmopolitan in its indifference to nationalist movements. It was only after the occupation of Prague that he saw that his detached reasonableness was insufficient to stop Hitler. The result was our guarantee to Poland, Greece, and Roumania, the introduction of conscription, and the intensification of rearmament.

- Viscount Templewood, Nine Troubled Years (1954), pp. 381-382

- [Neville Chamberlain] was a very honourable man ... I often thought he knew that in 1938 he must gain time to get us ready. I believe he gained more in that last year than Hitler ... it may be that we owe Chamberlain a great debt of gratitude for his judgment for what happened during those years. And it brought Winston forward that much more ... perhaps it has been one of the faults of British politicians that we look at other politicians through slightly rose-tinted spectacles thinking they are as we are.

- Margaret Thatcher, interview with Charles Moore, quoted in Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher. The Authorized Biography, Volume One: Not For Turning (2013), p. 19