Herbert Spencer

Appearance

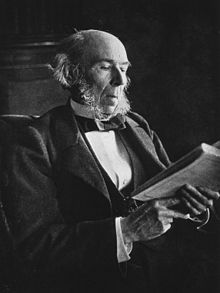

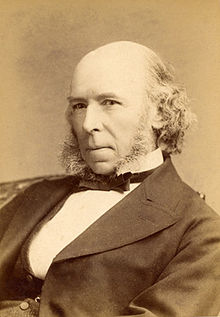

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, classical liberal political theorist, and sociological theorist of the Victorian era. He developed an all-embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies. He is known for coining the phrase "survival of the fittest".

Quotes

[edit]

- The current opinion that science and poetry are opposed is a delusion. ... Think you that a drop of water, which to the vulgar eye is but a drop of water, loses any thing in the eye of the physicist who knows that its elements are held together by a force which, if suddenly liberated, would produce a flash of lightning? Think you that what is carelessly looked upon by the uninitiated as a mere snow-flake does not suggest higher associations to one who has seen through a microscope the wondrously varied and elegant forms of snow-crystals? Think you that the rounded rock marked with parallel scratches calls up as much poetry in an ignorant mind as in the mind of a geologist, who knows that over this rock a glacier slid a million years ago? The truth is, that those who have never entered upon scientific pursuits know not a tithe of the poetry by which they are surrounded.

- Lectures on Education delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, London, 1855, published in "What Knowledge is of Most Worth", The Westminster Review (July 1859) volume CXLI, p. 1-23, at p. 19

- Time: That which man is always trying to kill, but which ends in killing him.

- Definitions, as quoted in The Dictionary of Essential Quotations (1983) by Kevin Goldstein-Jackson, p. 154

Social Statics (1851)

[edit]

- All evil results from the non-adaptation of constitution to conditions. This is true of everything that lives. Does a shrub dwindle in poor soil, or become sickly when deprived of light, or die outright if removed to a cold climate? it is because the harmony between its organization and its circumstances has been destroyed.

- Part I, Ch. 2 : The Evanescence of Evil, § 1

- Evil perpetually tends to disappear.

- Part I, Ch. 2 : The Evanescence of Evil, § 2

- Man needed one moral constitution to fit him for his original state; he needs another to fit him for his present state; and he has been, is, and will long continue to be, in process of adaptation. And the belief in human perfectibility merely amounts to the belief that, in virtue of this process, man will eventually become completely suited to his mode of life.

Progress, therefore, is not an accident, but a necessity. Instead of civilization being artificial, it is part of nature; all of a piece with the development of the embryo or the unfolding of a flower. The modifications mankind have undergone, and are still undergoing, result from a law underlying the whole organic creation; and provided the human race continues, and the constitution of things remains the same, those modifications must end in completeness.- Pt. I, Ch. 2 : The Evanescence of Evil, concluding paragraph

- Every man may claim the fullest liberty to exercise his faculties compatible with the possession of like liberties by every other man.

- Pt. II, Ch. 4 : Derivation of a First Principle, § 3

- Limiting the liberty of each by the like liberty of all, excludes a wide range of improper actions, but does not exclude certain other improper ones.

- Pt. II, Ch. 4 : Derivation of a First Principle, § 4

- Equity knows no difference of sex. In its vocabulary the word man must be understood in a generic, and not in a specific sense.

- Pt. II, Ch. 16 : The Rights of Women

- Attila conceived himself to have a divine claim to the dominion of the earth: — the Spaniards subdued the Indians under plea of converting them to Christianity; hanging thirteen refractory ones in honour of Jesus Christ and his apostles: and we English justify our colonial aggressions by saying that the Creator intends the Anglo-Saxon race to people the world! An insatiate lust of conquest transmutes manslaying into a virtue; and, amongst more races than one, implacable revenge has made assassination a duty. A clever theft was praiseworthy amongst the Spartans; and it is equally so amongst Christians, provided it be on a sufficiently large scale. Piracy was heroism with Jason and his followers; was so also with the Norsemen; is so still with the Malays; and there is never wanting some golden fleece for a pretext. Amongst money-hunting people a man is commended in proportion to the number of hours he spends in business; in our day the rage for accumulation has apotheosized work; and even the miser is not without a code of morals by which to defend his parsimony. The ruling classes argue themselves into the belief that property should be represented rather than person — that the landed interest should preponderate. The pauper is thoroughly persuaded that he has a right to relief. The monks held printing to be an invention of the devil; and some of our modern sectaries regard their refractory brethren as under demoniacal possession. To the clergy nothing is more obvious than that a state-church is just, and essential to the maintenance of religion. The sinecurist thinks himself rightly indignant at any disregard of his vested interests. And so on throughout society.

- Pt. II, Ch. 16 : The Rights of Women

- Education has for its object the formation of character. To curb restive propensities, to awaken dormant sentiments, to strengthen the perceptions, and cultivate the tastes, to encourage this feeling and repress that, so as finally to develop the child into a man of well proportioned and harmonious nature — this is alike the aim of parent and teacher.

- Pt. II, Ch. 17 : The Rights of Children

- As a corollary to the proposition that all institutions must be subordinated to the law of equal freedom, we cannot choose but admit the right of the citizen to adopt a condition of voluntary outlawry. If every man has freedom to do all that he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man, then he is free to drop connection with the state — to relinquish its protection, and to refuse paying towards its support. It is self-evident that in so behaving he in no way trenches upon the liberty of others; for his position is a passive one; and whilst passive he cannot become an aggressor. It is equally selfevident that he cannot be compelled to continue one of a political corporation, without a breach of the moral law, seeing that citizenship involves payment of taxes; and the taking away of a man's property against his will, is an infringement of his rights. Government being simply an agent employed in common by a number of individuals to secure to them certain advantages, the very nature of the connection implies that it is for each to say whether he will employ such an agent or not. If any one of them determines to ignore this mutual-safety confederation, nothing can be said except that he loses all claim to its good offices, and exposes himself to the danger of maltreatment — a thing he is quite at liberty to do if he likes. He cannot be coerced into political combination without a breach of the law of equal freedom; he can withdraw from it without committing any such breach; and he has therefore a right so to withdraw.

- “No human laws are of any validity if contrary to the law of nature; and such of them as are valid derive all their force and all their authority mediately or immediately from this original.” Thus writes Blackstone, to whom let all honour be given for having so far outseen the ideas of his time; and, indeed, we may say of our time. A good antidote, this, for those political superstitions which so widely prevail. A good check upon that sentiment of power-worship which still misleads us by magnifying the prerogatives of constitutional governments as it once did those of monarchs. Let men learn that a legislature is not “our God upon earth,” though, by the authority they ascribe to it, and the things they expect from it, they would seem to think it is. Let them learn rather that it is an institution serving a purely temporary purpose, whose power, when not stolen, is at the best borrowed.

- Pt. III, Ch. 19 : The Right to Ignore the State, § 2

- The poverty of the incapable, the distresses that come upon the imprudent, the starvation of the idle, and those shoulderings aside of the weak by the strong, which leave so many "in shallows and in miseries," are the decrees of a large, far-seeing benevolence.

- Pt. III, Ch. 25 : Poor-Laws

- Opinion is ultimately determined by the feelings, and not by the intellect.

- Pt. IV, Ch. 30 : General Considerations

- Morality knows nothing of geographical boundaries, or distinctions of race.

- Pt. IV, Ch. 30 : General Considerations

- No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; no one can be perfectly happy till all are happy.

- Pt. IV, Ch. 30 : General Considerations

The Development Hypothesis (1852)

[edit]

- The Development Hypothesis, first published in The Leader (20 March 1852), later published with revisions as [1] in various editions of Essays: Scientific, Political and Speculative (1852). This essay was written six years prior to the July 1, 1858 presentation of papers by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, to the Linnean Society of London, on the theory of evolution by natural selection. The following quotes are from the edition of Seven Essays, Selected from the Works of H. Spencer Watts & Co. (1907).

- Those who cavalierly reject the Theory of Evolution, as not adequately supported by facts, seem quite to forget that their own theory is supported by no facts at all. Like the majority of men who are born to a given belief, they demand the most rigorous proof of any adverse belief, but assume that their own needs none.

- Well, which is the most rational theory about these ten millions of species? Is it most likely that there have been ten millions of special creations? or is it most likely that, by continual modifications due to change of circumstances, ten millions of varieties have been produced, as varieties are being produced still?

- Should the believers in special creations consider it unfair thus to call upon them to describe how special creations take place, I reply that this is far less than they demand from the supporters of the Development Hypothesis. They are merely asked to point out a conceivable mode. On the other hand, they ask, not simply for a conceivable mode, but for the actual mode.

- The supporters of the Development Hypothesis... can show that any existing species—animal or vegetable—when placed under conditions different from its previous ones, immediately begins to undergo certain changes fitting it for the new conditions. They can show that in successive generations these changes continue; until, ultimately, the new conditions become the natural ones. They can show that in cultivated plants, in domesticated animals, and in the several races of men, such alterations have taken place. They can show that the degrees of difference so produced are often, as in dogs, greater than those on which distinctions of species are in other cases founded.

- Throughout all organic nature there is at work a modifying influence of the kind... as the cause, these specific differences: an influence which, though slow in its action, does, in time, if the circumstances demand it, produce marked changes—an influence, which to all appearance, would produce in the millions of years, and under the great varieties of condition which geological records imply, any amount of change.

- That by any series of changes a protozoon should ever become a mammal, seems to those who are not familiar with zoology, and who have not seen how clear becomes the relationship between the simplest and the most complex forms when intermediate forms are examined, a very grotesque notion. Habitually, looking at things rather in their statical aspect than in their dynamical aspect, they never realize the fact that, by small increments of modification, any amount of modification may in time be generated.

- The blindness of those who think it absurd to suppose that complex organic forms may have arisen by successive modifications out of simple ones becomes astonishing when we remember that complex organic forms are daily being thus produced. A tree differs from a seed immeasurably in every respect... Yet is the one changed in the course of a few years into the other: changed so gradually, that at no moment can it be said — Now the seed ceases to be, and the tree exists.

- That the uneducated and the ill-educated should think the hypothesis that all races of beings, man inclusive, may in process of time have been evolved from the simplest monad, a ludicrous one, is not to be wondered at. But for the physiologist, who knows that every individual being is so evolved—who knows, further, that in their earliest condition the germs of all plants and animals whatever are so similar, "that there is no appreciable distinction amongst them, which would enable it to be determined whether a particular molecule is the germ of a Conferva or of an Oak, of a Zoophyte or of a Man";—for him to make a difficulty of the matter is inexcusable.

- Spencer here references William Benjamin Carpenter, Principles of Comparative Physiology see p. 473

- Surely if a single cell may, when subjected to certain influences, become a man in the space of twenty years; there is nothing absurd in the hypothesis that under certain other influences, a cell may, in the course of millions of years, give origin to the human race.

- We have, indeed, in the part taken by many scientific men in this controversy of "Law versus Miracle," a good illustration of the tenacious vitality of superstitions. Ask one of our leading geologists or physiologists whether he believes in the Mosaic account of the creation, and he will take the question as next to an insult. Either he rejects the narrative entirely, or understands it in some vague non-natural sense. ...Whence ...this notion of "special creations"...Why, after rejecting all the rest of the story, he should strenuously defend this last remnant of it, as though he had received it on valid authority, he would be puzzled to say.

The Philosophy of Style (1852)

[edit]

- There can be little question that good composition is far less dependent upon acquaintance with its laws, than upon practice and natural aptitude. A clear head, a quick imagination, and a sensitive ear, will go far towards making all rhetorical precepts needless.

- Pt. I, sec. 1, "The Principle of Economy"

- We have a priori reasons for believing that in every sentence there is some one order of words more effective than any other; and that this order is the one which presents the elements of the proposition in the succession in which they may be most readily put together.

- Pt. I, sec. 3, "The Principle of Economy Applied to Sentences"

- Thus poetry, regarded as a vehicle of thought, is especially impressive partly because it obeys all the laws of effective speech, and partly because in so doing it imitates the natural utterances of excitement.

- Pt. I, sec. 6, "The Effect of Poetry Explained"

- The ideal form for a poem, essay, or fiction, is that which the ideal writer would evolve spontaneously. One in whom the powers of expression fully responded to the state of feeling, would unconsciously use that variety in the mode of presenting his thoughts, which Art demands.

- Pt. II, sec. 4, "The Ideal Writer"

Essays on Education (1861)

[edit]- Architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and poetry, may truly be called the efflorescence of civilised life.

- Education: What Knowledge Is of Most Worth?

- Every cause produces more than one effect.

- On Progress: Its Law and Cause

- The tyranny of Mrs. Grundy is worse than any other tyranny we suffer under.

- On Manners and Fashion

- Old forms of government finally grow so oppressive, that they must be thrown off even at the risk of reigns of terror.

- On Manners and Fashion

- Music must take rank as the highest of the fine arts — as the one which, more than any other, ministers to human welfare.

- On the Origin and Function of Music

Education: Intellectual, Moral, and Physical (1861)

[edit]- The education of the child must accord both in mode and arrangement with the education of mankind, considered historically. In other words, the genesis of knowledge in the individual, must follow the same course as the genesis of knowledge in the race. In strictness, this principle may be considered as already expressed by implication; since both being processes of evolution, must conform to those same general laws of evolution... and must therefore agree with each other. Nevertheless this particular parallelism is of value for the specific guidance it affords. To M. Comte we believe society owes the enunciation of it; and we may accept this item of his philosophy without at all committing ourselves to the rest.

- If there be an order in which the human race has mastered its various kinds of knowledge, there will arise in every child an aptitude to acquire these kinds of knowledge in the same order. So that even were the order intrinsically indifferent, it would facilitate education to lead the individual mind through the steps traversed by the general mind. But the order is not intrinsically indifferent; and hence the fundamental reason why education should be a repetition of civilization in little.

- It is provable both that the historical sequence was, in its main outlines, a necessary one; and that the causes which determined it apply to the child as to the race. ...as the mind of humanity placed in the midst of phenomena and striving to comprehend them has, after endless comparisons, speculations, experiments, and theories, reached its present knowledge of each subject by a specific route; it may rationally be inferred that the relationship between mind and phenomena is such as to prevent this knowledge from being reached by any other route; and that as each child's mind stands in this same relationship to phenomena, they can be accessible to it only through the same route. Hence in deciding upon the right method of education, an inquiry into the method of civilization will help to guide us.

First Principles (1862)

[edit]

- We too often forget that not only is there "a soul of goodness in things evil," but very generally also, a soul of truth in things erroneous.

- Pt. I, The Unknowable; Ch. I, Religion and Science; quoting from "There is some soul of goodness in things evil / Would men observingly distil it out", William Shakespeare, Henry V, act iv. sc. i

- The fact disclosed by a survey of the past that majorities have usually been wrong, must not blind us to the complementary fact that majorities have usually not been entirely wrong.

- Pt. I, The Unknowable; Ch. I, Religion and Science

- Each new ontological theory, propounded in lieu of previous ones shown to be untenable, has been followed by a new criticism leading to a new scepticism. All possible conceptions have been one by one tried and found wanting; and so the entire field of speculation has been gradually exhausted without positive result: the only result reached being the negative one above stated, that the reality existing behind all appearances is, and must ever be, unknown.

- Pt. I, The Unknowable; Ch. IV, The Relativity of All Knowledge

- Volumes might be written upon the impiety of the pious.

- Pt. I, The Unknowable; Ch. V, The Reconciliation

- Evolution is definable as a change from an incoherent homogeneity to a coherent heterogeneity, accompanying the dissipation of motion and integration of matter.

- Pt. II, The Knowable; Ch. XV, The Law of Evolution (continued)

- We have repeatedly observed that while any whole is evolving, there is always going on an evolution of the parts into which it divides itself; but we have not observed that this equally holds of the totality of things, which is made up of parts within parts from the greatest down to the smallest.

- Pt. II, The Knowable; Ch. XIV, Summary and Conclusion

Principles of Biology (1864)

[edit]

- If a single cell, under appropriate conditions, becomes a man in the space of a few years, there can surely be no difficulty in understanding how, under appropriate conditions, a cell may, in the course of untold millions of years, give origin to the human race.

- Vol. I, Part III: The Evolution of Life, Ch. 3 : General Aspects of the Evolution Hypothesis; compare: "As nine months go to the shaping an infant ripe for his birth, / So many a million of ages have gone to the making of man", Alfred Lord Tennyson, Maud (1855)

- It cannot but happen that those individuals whose functions are most out of equilibrium with the modified aggregate of external forces, will be those to die; and that those will survive whose functions happen to be most nearly in equilibrium with the modified aggregate of external forces.

But this survival of the fittest, implies multiplication of the fittest. Out of the fittest thus multiplied, there will, as before, be an overthrowing of the moving equilibrium wherever it presents the least opposing force to the new incident force.- The Principles of Biology, Vol. I (1864), Part III: The Evolution of Life, Ch. 7: Indirect Equilibration

- With a higher moral nature will come a restriction on the multiplication of the inferior.

- The Principles of Biology, Vol. II (1867), Part VI: Laws of Multiplication, ch. 8: Human Population in the Future

- We have unmistakable proof that throughout all past time, there has been a ceaseless devouring of the weak by the strong.

- Vol. I, Part III, Ch. 2 General Aspects of the Special-Creation-Hypothesis

The Man versus the State (1884)

[edit]The Coming Slavery

[edit]- "The Coming Slavery"; also published in The Contemporary Review (April 1884), p. 474

- Influences of various kinds conspire to increase corporate action and decrease individual action. And the change is being on all sides aided by schemers, each of whom thinks only of his pet plan and not at all of the general reorganization which his plan, joined with others such, are working out. It is said that the French Revolution devoured its own children. Here, an analogous catastrophe seems not unlikely. The numerous socialistic changes made by Act of Parliament, joined with the numerous others presently to be made, will by-and-by be all merged in State-socialism—swallowed in the vast wave which they have little by little raised.

"But why is this change described as 'the coming slavery'?," is a question which many will still ask. The reply is simple. All socialism involves slavery.

- What is essential to the idea of a slave? We primarily think of him as one who is owned by another. To be more than nominal, however, the ownership must be shown by control of the slave's actions — a control which is habitually for the benefit of the controller. That which fundamentally distinguishes the slave is that he labours under coercion to satisfy another's desires. The relation admits of sundry gradations. Remembering that originally the slave is a prisoner whose life is at the mercy of his captor, it suffices here to note that there is a harsh form of slavery in which, treated as an animal, he has to expend his entire effort for his owner's advantage. Under a system less harsh, though occupied chiefly in working for his owner, he is allowed a short time in which to work for himself, and some ground on which to grow extra food. A further amelioration gives him power to sell the produce of his plot and keep the proceeds. Then we come to the still more moderated form which commonly arises where, having been a free man working on his own land, conquest turns him into what we distinguish as a serf; and he has to give to his owner each year a fixed amount of labour or produce, or both: retaining the rest himself. Finally, in some cases, as in Russia before serfdom was abolished, he is allowed to leave his owner's estate and work or trade for himself elsewhere, under the condition that he shall pay an annual sum. What is it which, in these cases, leads us to qualify our conception of the slavery as more or less severe? Evidently the greater or smaller extent to which effort is compulsorily expended for the benefit of another instead of for self-benefit. If all the slave's labour is for his owner the slavery is heavy, and if but little it is light. Take now a further step. Suppose an owner dies, and his estate with its slaves comes into the hands of trustees; or suppose the estate and everything on it to be bought by a company; is the condition of the slave any the better if the amount of his compulsory labour remains the same? Suppose that for a company we substitute the community; does it make any difference to the slave if the time he has to work for others is as great, and the time left for himself is as small, as before? The essential question is—How much is he compelled to labour for other benefit than his own, and how much can he labour for his own benefit? The degree of his slavery varies according to the ratio between that which he is forced to yield up and that which he is allowed to retain; and it matters not whether his master is a single person or a society. If, without option, he has to labour for the society, and receives from the general stock such portion as the society awards him, he becomes a slave to the society.

The Sins of Our Legislators

[edit]- Be it or be it not true that Man is shapen in iniquity and conceived in sin, it is unquestionably true that Government is begotten of aggression, and by aggression. In small undeveloped societies where for ages complete peace has continued, there exists nothing like what we call Government: no coercive agency, but mere honorary headship, if any headship at all. In these exceptional communities, unaggressive and from special causes unaggressed upon, there is so little deviation from the virtues of truthfulness, honesty, justice, and generosity, that nothing beyond an occasional expression of public opinion by informally-assembled elders is needful. Conversely, we find proofs that, at first recognized but temporarily during leadership in war, the authority of a chief is permanently established by continuity of war; and grows strong where successful aggression ends in subjection of neighboring tribes. And thence onwards, examples furnished by all races put beyond doubt the truth, that the coercive power of the chief, developing into king, and king of kings (a frequent title in the ancient East), becomes great in proportion as conquest becomes habitual and the union of subdued nations extensive. Comparisons disclose a further truth which should be ever present to us — the truth that the aggressiveness of the ruling power inside a society increases with its aggressiveness outside the society. As, to make an efficient army, the soldiers in their several grades must be subordinate to the commander; so, to make an efficient fighting community, must the citizens be subordinate to the ruling power. They must furnish recruits to the extent demanded, and yield up whatever property is required.

An obvious implication is that the ethics of Government, originally identical with the ethics of war, must long remain akin to them; and can diverge from them only as warlike activities and preparations become less.

Essays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative (1891)

[edit]

- The saying that beauty is but skin deep is but a skin-deep saying.

- Vol. 2, Ch. XIV, Personal Beauty

- Under the natural course of things each citizen tends towards his fittest function. Those who are competent to the kind of work they undertake, succeed, and, in the average of cases, are advanced in proportion to their efficiency; while the incompetent, society soon finds out, ceases to employ, forces to try something easier, and eventually turns to use.

- Vol. 3, Ch. VII, Over-Legislation

- Unlike private enterprise which quickly modifies its actions to meet emergencies — unlike the shopkeeper who promptly finds the wherewith to satisfy a sudden demand — unlike the railway company which doubles its trains to carry a special influx of passengers; the law-made instrumentality lumbers on under all varieties of circumstances at its habitual rate. By its very nature it is fitted only for average requirements, and inevitably fails under unusual requirements.

- Vol. 3, Ch. VII, Over-Legislation

- Strong as it looks at the outset, State-agency perpetually disappoints every one. Puny as are its first stages, private efforts daily achieve results that astound the world.

- Vol. 3, Ch. VII, Over-Legislation

- The ultimate result of shielding men from the effects of folly, is to fill the world with fools.

- Vol. 3, Ch. IX, State-Tamperings with Money and Banks

- The Republican form of government is the highest form of government; but because of this it requires the highest type of human nature — a type nowhere at present existing.

- Vol. 3, Ch. XV, The Americans

- The primary use of knowledge is for such guidance of conduct under all circumstances as shall make living complete. All other uses of knowledge are secondary.

- Vol. 3, Ch. XV, The Americans

The Principles of Ethics (1897)

[edit]Part I: The Data of Ethics

[edit]- Every pleasure raises the tide of life; every pain lowers the tide of life.

- Ch. 6, The Biological View

- The essential trait in the moral consciousness, is the control of some feeling or feelings by some other feeling or feelings.

- Ch. 7, The Psychological View

- The universal basis of co-operation is the proportioning of benefits received to services rendered.

- Ch. 8, The Sociological View

- People ... become so preoccupied with the means by which an end is achieved, as eventually to mistake it for the end. Just as money, which is a means of satisfying wants, comes to be regarded by a miser as the sole thing to be worked for, leaving the wants unsatisfied; so the conduct men have found preferable because most conducive to happiness, has come to be thought of as intrinsically preferable: not only to be made a proximate end (which it should be), but to be made an ultimate end, to the exclusion of the true ultimate end.

- Ethics (New York:1915), § 14, pp. 38-39

- If insistence on them tends to unsettle established systems ... self-evident truths are by most people silently passed over; or else there is a tacit refusal to draw from them the most obvious inferences.

- Ethics (New York:1915), § 68, p. 187

- The pursuit of individual happiness within those limits prescribed by social conditions, is the first requisite to the attainment of the greatest general happiness.

- Ethics (New York:1915), § 70, pp. 190-191

- He who carries self-regard far enough to keep himself in good health and high spirits, in the first place thereby becomes an immediate source of happiness to those around, and in the second place maintains the ability to increase their happiness by altruistic actions. But one whose bodily vigour and mental health are undermined by self-sacrifice carried too far, in the first place becomes to those around a cause of depression, and in the second place renders himself incapable, or less capable, of actively furthering their welfare. In estimating conduct we must remember that there are those who by their joyousness beget joy in others, and that there are those who by their melancholy cast a gloom on every circle they enter.

- Ethics (New York:1915), § 72, pp. 193-194

Part II: The Inductions of Ethics

[edit]- Originally, ethics has no existence apart from religion, which holds it in solution.

- Ch. 1, The Confusion of Ethical Thought

- How often misused words generate misleading thoughts!

- Ch. 8, Humanity

Part III: The Ethics of Individual Life

[edit]- Ethical ideas and sentiments have to be considered as parts of the phenomena of life at large. We have to deal with man as a product of evolution, with society as a product of evolution, and with moral phenomena as products of evolution.

- Ch. 1, Introductory

- As there must be moderation in other things, so there must be moderation in self-criticism. Perpetual contemplation of our own actions produces a morbid consciousness, quite unlike that normal consciousness accompanying right actions spontaneously done; and from a state of unstable equilibrium long maintained by effort, there is apt to be a fall towards stable equilibrium, in which the primitive nature reasserts itself. Retrogression rather than progression may hence result.

- Ch. 10, General Conclusions

Part IV: The Ethics of Social Life: Justice

[edit]- Every man is free to do that which he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man.

- Ch. 6, The Formula of Justice

Facts and Comments (1902)

[edit]- When men hire themselves out to shoot other men to order, asking nothing about the justice of their cause, I don't care if they are shot themselves.

Misattributed

[edit]- There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all arguments and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance — that principle is contempt prior to investigation.

- Commonly attributed to Spencer, information provided in The Quote Verifier: Who Said What, Where, and When (2006) by Ralph Keyes and The Survival of a Fitting Quotation. (2005) by Michael StGeorge, indicates the attribution may have originated with the book [w:The_Big_Book_(Alcoholics_Anonymous)|Alcoholics Anonymous]]. It was used exactly as written above in the personal stories section of the first edition in 1939 and in 'Appendix II: Spiritual Experience' of all subsequent editions.

- "Contempt prior to examination" was a phrase used by William Paley, the 18th-century English Christian apologist. In A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794), he wrote:

- The infidelity of the Gentile world, and that more especially of men of rank and learning in it, is resolved into a principle which, in my judgment, will account for the inefficacy of any argument, or any evidence whatever, viz. contempt prior to examination.

- Paley's characterization of non-believers was later modified and used by other religious authors who uniformly attributed their words to Paley. In Anglo-Israel or, The British Nation: The lost Tribes of Israel (1879), Rev. William H. Poole may have been the first to render the quotation in its more familiar and enduring form:

- There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all argument, and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance. This principle is, contempt prior to examination.

- Various authors following Rev. Poole would offer new iterations of the quotation into the early decades of the 20th century. Most of these credited William Paley, but by the early 1930s the first obscure publications to falsely attribute this quote to Spencer emerged. Its usage for decades since as a maxim in Alcoholics Anonymous and the twelve-step recovery community has popularized its erroneous association with Herbert Spencer.

- "Contempt prior to examination" was a phrase used by William Paley, the 18th-century English Christian apologist. In A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794), he wrote:

Quotes about Spencer

[edit]- Spencer argued in a very articulate way for the communality of these processes of self-organization, and used his ideas to make a theory of sociology. However, he was not able to put these ideas into mathematical form or argue them from first principles. And no one else has, either — doing so is perhaps the central problem in the study of complex systems.

- J. Doyne Farmer, The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution ed. John Brockman (1995)

- One of the factors that caused Spencer's ideas to lose popularity was social Darwinism... Social evolution is different from biological evolution: it's faster, it's Lamarckian, and it makes even heavier use of altruism and cooperation than biological evolution does. None of this was well understood at the time.

- J. Doyne Farmer, The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution ed. John Brockman (1995)

- In the words of Herbert Spencer, I would say that “in proportion as the principle of voluntary cooperation more and more characterizes the social type, the implied assertion of equality in... rights become the fundamental requirement of... law."

- Anna Kuliscioff Il monopolio dell'uomo: conferenza tenuta nel circolo filologico milanese (1894) translated from the Italian into The Monopoly of Man by Lorenzo Chiesa (2021)

- Herbert Spencer, who was ever undone by his love of classification.

- Rebecca West, "Quiet Women of the Country", in The Clarion, (31 January 1913); in re-published in The Young Rebecca: Writings of Rebecca West, 1911-17 (1982), p. 152.

- Spencer had a photo of Marian (George Eliot) in his bedroom until the day he died. The sisters who kept house for him in the 1890s used to tease him about it.

"What a long nose she had! She must have been very difficult to kiss, Mr Spencer!"

"Yes indeed! he brightly acquiesced, to our intense delight at the apparent admission. He laughingly protested he was speaking theoretically; but would Herbert Spencer, the philosopher, have generalised from an a priori reasoning?"- George Eliot a Biography. Gordon S. Height. Clarendon Press 1968. Home Life with Herbert Spencer, by Two (1906).

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- "Herbert Spencer" by William Sweet in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Profile by David Weinstein in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Works by Herbert Spencer at Project Gutenberg

- A System of Synthetic Philosophy

- "First principles" at the Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library

- "The Right to Ignore the State" (Ch. 29 of Social Statics by Spencer

- Extensive biography and overview of works

- Review materials for studying Herbert Spencer

- "Herbert Spencer: The Defamation Continues" by Roderick T. Long

- First Principles Herbert's 'First Principles' online

- Excerpts from Progress: Its Law and Cause available from the Internet Modern History Sourcebook

- Modern History Sourcebook: Herbert Spencer: Social Darwinism, 1857

- Spencer's ideas