Coronavirus disease 2019

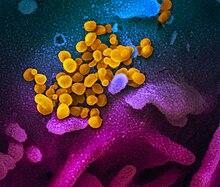

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province, and has since spread globally, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Quotes

[edit]- WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

Risk for severe COVID-19 increases with age, disability, and underlying medical conditions. The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is more infectious but has been associated with less severe disease.

- WHAT IS ADDED BY THIS REPORT?

In-hospital mortality among patients hospitalized primarily for COVID-19 decreased from 15.1% (Delta period) to 4.9% (later Omicron period; April–June 2022), despite high-risk patient groups representing a larger proportion of hospitalizations. During the later Omicron period, the majority of in-hospital deaths occurred among adults aged ≥65 years (81.9%) and persons with three or more underlying medical conditions (73.4%).

- WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH PRACTICE?

Vaccination, early treatment, and appropriate nonpharmaceutical interventions remain important public health priorities to prevent COVID-19 deaths, especially among persons most at risk.

- Some people who have been infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 can experience long-term effects from their infection, known as post-COVID conditions (PCC) or long COVID. The working was developed by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in collaboration with CDC and other partners.

- People call post-COVID conditions by many names, including: Long COVID, long-haul COVID, post-acute COVID-19, post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (PASC), long-term effects of COVID, and chronic COVID.

- CDC Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions (Updated Dec. 16, 2022 Español | Other Languages)

Disease characteristics

[edit]

"If you want to understand what an aerosol is, just think of somebody smoking," Osterholm told CNN. "If you can smell a cigarette in the location you're at, then you're breathing someone else's air that may have the virus in it. ~ Travis Caldwell

Now, even a quick, transient encounter can lead to an infection, Reiner added, including if someone's mask is loose, or a person quickly pulls their mask down, or an individual enters an elevator in which someone else has just coughed.

"This is how you can contract this virus," Reiner said. ~ Christina Maxouris quoting Jonathan Reiner

- Historian John Barry, who wrote the definitive account of the Spanish flu, “The Great Influenza,” noted there are significant differences between Covid infection and transmission and influenza infection and transmission. The incubation period — the time from exposure to illness — is longer with Covid. People are sick for longer; they’re infectious for longer, too.

“This is like influenza moving in very slow motion,” Barry said. Influenza pandemics have abrupt endings to their waves, with transmission dying out in any given location in a matter of weeks. That has not been the case with Covid. Instead, human behavior — societal shutdowns and reopenings — appear to be driving patterns.- John Barry as quoted by Helen Branswell in ”How the Covid pandemic ends: Scientists look to the past to see the future”, STAT, (May 19, 2021)

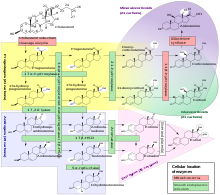

- "It's a very complicated receptor binding process compared to most virus spike proteins," Benton said. "Flu and HIV have a more simple activation process." The coronavirus is covered in spike proteins, and it's likely only a small fraction of them go through these conformational changes, bind to human cells and infect them, Benton said.

We know that the spike can adopt all these states that we were talking about," said co-lead author Antoni Wrobel, who is also a postdoctoral research fellow at the Francis Crick Institute's Structural Biology of Disease Processes Laboratory. "But whether each of the spikes adopts all of them we can't say because we can see only kind of snapshots."

The spike protein is very quick to change. In the lab, the spike can morph into all of these different conformations in less than 60 seconds, Wrobel told Live Science. But "this will be very different in a real infection; everything will be slower because the receptor will be stuck on the surface of a cell so you have to allow time for the virus to diffuse to this receptor," Benton said.

Why does the spike protein go through this many conformational changes to infect a cell? It "may be a way of the virus protecting itself from recognition by antibodies," Benton said. When the spike protein is in its closed states, it hides the site that binds with the receptor, maybe to avoid antibodies coming in and binding to that site instead, he said.- Donald Benton and Antoni Wrobel as quoted by Yasemin Saplakoglu in ”Coronavirus spike protein morphs into 10 different shapes to invade cells”, Live Science, (September 28, 2020)

- Aerosols containing Covid-19 can travel as easily as the smoke from a cigarette, Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said Friday.

"If you want to understand what an aerosol is, just think of somebody smoking," Osterholm told CNN. "If you can smell a cigarette in the location you're at, then you're breathing someone else's air that may have the virus in it."- Travis Caldwell, “The surge of Covid-19 infections for unvaccinated people is only beginning, experts warn”, CNN, July 31, 2021

- This study was the first study to examine the individual and synergistic effects of AT and RH on coronavirus survival on surfaces. The results show that when high numbers of the surrogates TGEV and MHV are deposited, these viruses may survive for days on surfaces at the ambient AT and wide range of RH levels (20 to 60% RH) typical of health care environments. TGEV and MHV may be more resistant to inactivation on surfaces than previously studied human coronaviruses, such as 229E (28). SARS-CoV has been reported to survive for 36 h on stainless steel, but the reductions in the levels observed were greater than those seen for either TGEV or MHV at 20°C at any RH in this study. However, the AT and RH conditions for the previous experiment were not reported, making comparisons difficult. Rabenau et al. reported much slower inactivation of SARS-CoV on a polystyrene surface (4 log10 reduction after 9 days; AT and RH conditions not reported), consistent with some observations for TGEV and MHV in the present study. There are some similarities with studies of another enveloped virus, human influenza virus, on surfaces in that at higher RH (50 to 60%), the inactivation kinetics are closer to those of TGEV and MHV.

- Lisa M. Casanova, Soyoung Jeon, William A. Rutala, David J. Weber, and Mark D. Sobsey; “Effects of Air Temperature and Relative Humidity on Coronavirus Survival on Surfaces”, Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 May; 76(9): 2712–2717.

- The survival data for TGEV and MHV suggest that enveloped viruses can remain infectious on surfaces long enough for people to come in contact with them, posing a risk for exposure that leads to infection and possible disease transmission. This risk may also occur for other enveloped viruses, such as influenza virus (3, 4). The potential reemergence of SARS or the emergence of new strains of pandemic influenza virus, including avian and swine influenza viruses, could pose serious risks for nosocomial disease spread via contaminated surfaces. However, this risk is still poorly understood, and more work is needed to quantify the risk of exposure and possible transmission associated with surfaces. Statistical analysis showed that TGEV and MHV do not differ significantly in their inactivation kinetics on surfaces, and both viruses may be suitable models for survival and inactivation of SARS-CoV on surfaces. However, more data on the survival rates and inactivation kinetics of SARS-CoV itself are needed before these relationships with other coronaviruses can be definitively established. However, the findings of this study suggest that TGEV and MHV could serve as conservative surrogates for modeling exposure, transmission risk, and control measures for pathogenic enveloped viruses, such as SARS-CoV and influenza viruses, on health care surfaces.

- Lisa M. Casanova, Soyoung Jeon, William A. Rutala, David J. Weber, and Mark D. Sobsey; “Effects of Air Temperature and Relative Humidity on Coronavirus Survival on Surfaces”, Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 May; 76(9): 2712–2717.

- For months, scientists have observed trends showing older people and men tend to be more vulnerable. Scientists know something about why children tend to have less serious infections from coronavirus -- they have fewer ACE2 receptors in their noses, and these receptors are how coronavirus gets into our cells. But they can't really explain why older people have such a high death rate from coronavirus -- much higher than from the common flu.

"What is it about age that makes you so much more susceptible to having disease?" Collignon questioned. "We've got the data and we know it's true ... but I don't think we've got all the answers for that."- Peter Collignon, as quoted in “Coronavirus has been with us for a year. Here's what we still don't know”, by Julia Hollingsworth, CNN, (28/12/2020)

- The problem, says Collignon, is that not enough money is spent on answering the basics.

"We spend billions of dollars on vaccines and drugs, but you can't get funding to do research on basics like how effective is this mask versus that mask," he said, adding that was partly because answers to those questions didn't make the problem go away -- they just decreased the risk.- Peter Collignon, as quoted in “Coronavirus has been with us for a year. Here's what we still don't know”, by Julia Hollingsworth, CNN, (28/12/2020)

- SARS-CoV-2 remained viable in aerosols throughout the duration of our experiment (3 hours), with a reduction in infectious titer from 103.5 to 102.7 TCID50 per liter of air. This reduction was similar to that observed with SARS-CoV-1, from 104.3 to 103.5 TCID50 per milliliter (Figure 1A).

SARS-CoV-2 was more stable on plastic and stainless steel than on copper and cardboard, and viable virus was detected up to 72 hours after application to these surfaces (Figure 1A), although the virus titer was greatly reduced (from 103.7 to 100.6 TCID50 per milliliter of medium after 72 hours on plastic and from 103.7 to 100.6 TCID50 per milliliter after 48 hours on stainless steel). The stability kinetics of SARS-CoV-1 were similar (from 103.4 to 100.7 TCID50 per milliliter after 72 hours on plastic and from 103.6 to 100.6 TCID50 per milliliter after 48 hours on stainless steel). On copper, no viable SARS-CoV-2 was measured after 4 hours and no viable SARS-CoV-1 was measured after 8 hours. On cardboard, no viable SARS-CoV-2 was measured after 24 hours and no viable SARS-CoV-1 was measured after 8 hours (Figure 1A).

Both viruses had an exponential decay in virus titer across all experimental conditions, as indicated by a linear decrease in the log10TCID50 per liter of air or milliliter of medium over time (Figure 1B). The half-lives of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1 were similar in aerosols, with median estimates of approximately 1.1 to 1.2 hours and 95% credible intervals of 0.64 to 2.64 for SARS-CoV-2 and 0.78 to 2.43 for SARS-CoV-1 (Figure 1C, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The half-lives of the two viruses were also similar on copper. On cardboard, the half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was longer than that of SARS-CoV-1. The longest viability of both viruses was on stainless steel and plastic; the estimated median half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was approximately 5.6 hours on stainless steel and 6.8 hours on plastic (Figure 1C). Estimated differences in the half-lives of the two viruses were small except for those on cardboard (Figure 1C). Individual replicate data were noticeably “noisier” (i.e., there was more variation in the experiment, resulting in a larger standard error) for cardboard than for other surfaces (Fig. S1 through S5), so we advise caution in interpreting this result.

We found that the stability of SARS-CoV-2 was similar to that of SARS-CoV-1 under the experimental circumstances tested. This indicates that differences in the epidemiologic characteristics of these viruses probably arise from other factors, including high viral loads in the upper respiratory tract and the potential for persons infected with SARS-CoV-2 to shed and transmit the virus while asymptomatic.3,4 Our results indicate that aerosol and fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is plausible, since the virus can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours and on surfaces up to days (depending on the inoculum shed). These findings echo those with SARS-CoV-1, in which these forms of transmission were associated with nosocomial spread and super-spreading events,5 and they provide information for pandemic mitigation efforts.- Neeltje van Doremalen, Trenton Bushmaker, Dylan H. Morris, Myndi G. Holbrook, Amandine Gamble, Brandi N. Williamson, Azaibi Tamin, Jennifer L. Harcourt, Natalie J. Thornburg, Susan I. Gerber, James O. Lloyd-Smith, Emmie de Wit, Vincent J. Munster; “Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1”, N Engl J Med, (April 16, 2020); 382:1564-1567

- There’s no evidence yet to suggest any ethnic group is at greater risk of complications from the coronavirus because of a lack of immunity since the virus is new to all humans, said Dr. Jehan El-Bayoumi, founding director of the Rodham Institute at the George Washington University.

But other social and economic factors — such as nutrition, access to health care and poverty — do increase the risk of complications in indigenous and minority communities, El-Bayoumi said.

“We know that 80 percent of the outcomes related to any illness actually has nothing to do with access to health care, it is really the social determinants of health,” she said. “Those include water that you drink, the air that you breathe, the food that you eat, your education, your economic background, (or) systemic racism.”- Jehan El-Bayoumi as quoted by Linda Givetash, ”'They're so vulnerable': Coronavirus hits tribes of isolated Andaman Islands”, NBC News, (Sept. 2, 2020)

- Thomas Gilbert, an associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, says coronavirus’s chemical make-up can be disrupted by nothing more specialised than cheap soap and warm water.

“These viruses have membranes that surround the genetic particles that are called lipid membranes, because they have an oily, greasy structure,” he says. “It’s this kind of structure than be neutralised by soap and water.” Dissolving this outer “envelope” breaks the virus cell up, and the genetic material – the RNA which hijacks human cells to make copies of the virus – is swept away and destroyed.

“I’ve heard of nothing yet to make the handwashing time shorter,” says Gilbert. “What you want to be doing is wetting your hands, getting the soap and working up a proper lather and then rubbing your hands for a good 20 seconds and get into all the nooks and crannies.” This gives enough time, Gilbert says, for the chemical reaction to take place between the lipid membrane and the soap. “There are other benefits – it also allows the soap to do a good job getting rid of the material.” And with warm water, Gilbert adds, all that virus fighting “happens a little quicker”.- Thomas Gilbert as quoted by Stephen Dowling in “Is a 20-second handwash enough to kill Covid-19?”, BBC Future, (20th August 2020)

- When SARS hit (the Southern China region) 17 years ago (in 2002-2003), Macau was lucky enough that it recorded only one imported case. But now, the (COVID-19) viral pneumonia coincides with the peak domestic travel season for Chinese New Year across China. That huge passenger traffic means the disease could be spread to each of the Chinese province.

- Ho Iat Seng (2020) cited in "Macau multi-stage response to pandemic risk: city chief" on GGR Asia, 23 January 2020.

- It was important to make the (COVID-19) disease notifiable. Although it did not appear to be as deadly as the previous SARS and MERS strains, there was still much to learn about it.

- Lance Jennings (2020) cited in: "China coronavirus checks: 'Looking for a needle in a haystack'" in RNZ, 27 January 2020.

- If the (COVID-19) infected (patient) droplets were sneezed at you by a patient and enters your eyes, they will eventually be washed from your eyes to your nose, as both are connected through what is known as a nasolacrimal duct.

- Paul Kellam (2020) cited in "Medical Experts Claim Wuhan Virus May Be Transmitted Through Your Eyes Or By Touch Alone" on World of Buzz, 31 January 2020.

- We didn't know until the last 24 hours.

- Brian Kemp, governor of Georgia, on that asymptomatic COVID-19 infected individuals can transmit the disease, in a CNN interview recorded in April 2020

- The SARS-CoV-2 virus is genetically closely related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the first pandemic threat of a novel and deadly coronavirus that emerged in late 2002 and caused an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS-CoV was highly lethal but faded out after intense public health mitigation measures. By contrast, the novel SARS-CoV-2 that emerged in December, 2019, rapidly caused a global pandemic. The SARS 2003 outbreak ceased in June, 2003, with a global total of 8098 reported cases and 774 deaths, and a case fatality rate of 9•7%, with most cases being acquired nosocomially. In comparison, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—another deadly coronavirus, but which is currently not presenting a pandemic threat—emerged in 2012, and has caused 2494 reported cases and 858 deaths in 27 countries and has a very high case fatality rate of 34%. Because MERS-CoV is widespread in dromedary camels, zoonotic cases continue to occur, unlike SARS-CoV, which emerged from wildlife and was eliminated from the intermediate host reservoir.

The new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is less deadly but far more transmissible than MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV. The virus emerged in December, 2019, and as of June 29, 2020, 6 months into the first pandemic wave, the global count is rapidly approaching 10 million known cases and has passed 500 000 deaths. Because of its broad clinical spectrum and high transmissibility, eradicating SARS-CoV-2, as was done with SARS-CoV in 2003, does not seem a realistic goal in the short term.- Jason T. Ladner, Sierra N. Henson, Annalee S. Boyle, Anna L. Engelbrektson, Zane W. Fink, Fatima Rahee, Jonathan D’ambrozio, Kurt E. Schaecher, Mars Stone, Wenjuan Dong, Sanjeet Dadwal, Jianhua Yu, Michael A. Caligiuri, Piotr Cieplak, Magnar Bjørås, Mona H. Fenstad, Svein A. Nordbø, Denis E. Kainov, Norihito Muranaka, Mark S. Chee, Sergey A. Shiryaev, John A. Altin; “Epitope-resolved profiling of the SARS-CoV-2 antibody response identifies cross-reactivity with endemic human coronaviruses”. Cell Reports Medicine, 2021; 2 (1): 100189 DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100189

- There is nothing in recent history that compares to a contagious crisis of this magnitude, according to historians who study infectious diseases and disasters. The H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009 infected an estimated 60.8 million people in its first year, but the virus wasn’t nearly as severe as Covid-19, killing between 151,700 and 575,400 worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MERS, another coronavirus that emerged in 2012, was much deadlier than Covid but significantly less infectious with only 2,494 reported cases.

- Berkeley Lovelace Jr., “Medical historian compares the coronavirus to the 1918 flu pandemic: Both were highly political”, CNBC, (Sep 28 2020; updated Sep 29 2020)

- China must have realized the epidemic did not originate in that Wuhan Huanan seafood market. The presumed rapid spread of the (COVID-19) virus apparently for the first time from the Huanan seafood market in December (2019) did not occur. Instead, the virus was already silently spreading in Wuhan, hidden amid many other patients with pneumonia at this time of year. The virus came into that marketplace before it came out of that marketplace.

- Daniel Lucey (2020) cited in "Scientists rush to find 'Patient Zero' in a bid to stop the coronavirus" on NZ Herald, 1 February 2020.

- At present (26 January 2020), the rate of development of the (COVID-19) epidemic is accelerating. I am afraid that it will continue for some time, and the number of cases may increase.

- Ma Xiaowei (2020) cited in "Wuhan Coronavirus Can Be Infectious Before People Show Symptoms, Official Claims" on Science Alert, 26 January 2020.

- Virus particles dilute rapidly outdoors. Virginia Tech aerosol expert Linsey Marr has compared it to a droplet of dye in the ocean: "If you happen to be right next to it, then maybe you'll get a whiff of it. But it's going to become diluted rapidly into the huge atmosphere."

- Linsey Marr as quoted by Sheila Mulrooney Eldred, “Coronavirus FAQ: I'm Vaccinated. I Thought I Could Give Up Masks! But Should I?, NPR, (July 26, 2021)

- Martin Michaelis, a professor of molecular science at the University of Kent in the UK, says water on its own is not enough to disable the virus. “When you have olive oil on your fingers when you’re cooking, it’s very hard to get rid of it with just water,” he says. “You need soap.” When it comes to the coronavirus, soap is needed in the same way “to remove that lipid envelope so that all the virus is deactivated”.

- Martin Michaelis as quoted by Stephen Dowling in “Is a 20-second handwash enough to kill Covid-19?”, BBC Future, (20th August 2020)

- If a person infected with the coronavirus sneezes, coughs or talks loudly, droplets containing particles of the virus can travel through the air and eventually land on nearby surfaces. But the risk of getting infected from touching a surface contaminated by the virus is low, says Emanuel Goldman, a microbiologist at Rutgers University.

"In hospitals, surfaces have been tested near COVID-19 patients, and no infectious virus can be identified," Goldman says.

What's found is viral RNA, which is like "the corpse of the virus," he says. That's what's left over after the virus dies.

"They don't find infectious virus, and that's because the virus is very fragile in the environment — it decays very quickly," Goldman says.

Back in January and February, scientists and public health officials thought surface contamination was a problem. In fact, early studies suggested the virus could live on surfaces for days.

It was assumed transmission occurred when an infected person sneezed or coughed on a nearby surface and "you would get the disease by touching those surfaces and then transferring the virus into your eyes, nose or mouth," says Linsey Marr, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech who studies airborne transmission of infectious disease.- Patti Neighmond quoting Emanuel Goldman and Linsey Marr; ”Still Disinfecting Surfaces? It Might Not Be Worth It”, Morning Edition, NPR, (December 28, 2020)

- Scientists now know that the early surface studies were done in pristine lab conditions using much larger amounts of virus than would be found in a real-life scenario.

Even so, many of us continue to attack door handles, packages and groceries with disinfectant wipes, and workers across the U.S. spend hours disinfecting surfaces in public areas like airports, buildings and subways.

There's no scientific data to justify this, says Dr. Kevin Fennelly, a respiratory infection specialist with the National Institutes of Health.

"When you see people doing spray disinfection of streets and sidewalks and walls and subways, I just don't know of any data that supports the fact that we're getting infected from viruses that are jumping up from the sidewalk."- Patti Neighmond quoting Kevin Fennelly, ”Still Disinfecting Surfaces? It Might Not Be Worth It”, Morning Edition, NPR, (December 28, 2020)

- It's still unclear whether that takes place (that COVID-19 can spread before people show signs of being infected). But if it does, that might explain why the disease is spreading so quickly.

- Malik Peiris (2020) cited in "Number of Coronavirus Cases Passes SARS Outbreak" on Learning English, 29 January 2020.

- Dr. Susan Rehm, vice chair at the Cleveland Clinic’s department of infectious diseases, said another reason flu incidences are low is because most people have some innate immunity from prior vaccinations and infections.

“COVID is a novel infection caused by the SARS coronavirus, and no one has any innate immunity to it,” she said. “So the population is probably overall more susceptible to it than maybe to influenza.”- Adrianna Rodriguez quoting Susan Rehm in “Record low flu cases show how COVID-19 is more contagious and 'less forgiving,' experts say”, USA TODAY, (January 11, 2021)

- "At the beginning of this pandemic... we all were taught, you have a significant exposure if you're within six feet of somebody and you're in contact with them for more than 15 minutes. All these rules are out the window," Reiner said. "This is a hyper-contagious virus."

Now, even a quick, transient encounter can lead to an infection, Reiner added, including if someone's mask is loose, or a person quickly pulls their mask down, or an individual enters an elevator in which someone else has just coughed.

"This is how you can contract this virus," Reiner said.- Christina Maxouris quoting Jonathan Reiner in “The Covid-19 case surge is altering daily life across the US. Things will likely get worse, experts warn”, CNN, January 1, 2022

- The first seropositive samples in our study were already detected during the week of 23 February, one week before the first confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 in NYC was identified, which suggests that SARS-CoV-2 was probably introduced to the NYC area several weeks earlier than has previously been assumed. This would not be unexpected given the unique diversity and connectivity of NYC and the large numbers of travellers that were arriving from SARS-CoV-2-affected regions of the world in January and February 2020. The antibody titres of initial positive individuals were low, which is consistent with slower seroconversion of perhaps mild cases. Of course, we cannot exclude with absolute certainty that some of the lower positive titres are false positives as the initially low seroprevalence falls within the confidence intervals of the positive predictive value.

Of note, the seroprevalence in the routine care group (as well as the urgent care group at the end of May, after the peak) falls significantly below the threshold for potential community immunity, which has been estimated by one study to require at least a seropositivity rate of 67% for SARS-CoV-24. On the basis of the population of NYC (8.4 million), we estimate that by the week ending 24 May, approximately 1.7 million individuals had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Taking into account the cumulative number of deaths in the city by 19 May (16,674—this number includes only officially confirmed, not suspected, COVID-19-related deaths), this suggests a preliminary infection fatality rate of 0.97% (with the assumption that both seroconversion and death occur with similar delays). This is in stark contrast to the infection fatality rate of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which was estimated to be 0.01–0.001%.- Daniel Stadlbauer, Jessica Tan, Kaijun Jiang, Matthew M. Hernandez, Shelcie Fabre, Fatima Amanat, Catherine Teo, Guha Asthagiri Arunkumar, Meagan McMahon, Christina Capuano, Kathryn Twyman, Jeffrey Jhang, Michael D. Nowak, Viviana Simon, Emilia Mia Sordillo, Harm van Bakel & Florian Krammer; “Repeated cross-sectional sero-monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in New York City”, Nature, (03 November 2020)

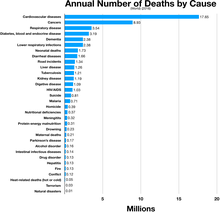

- Both influenza and coronaviruses cause respiratory tract infection that can lead to morbidity and mortality, especially in those who are immunocompromised or who have no existing immunity to the viruses. Indeed, while the COVID-19 should not be taken lightly, influenza is a much bigger problem, but because it is relatively common and has been around for a long time, it does not receive the attention that new viral outbreaks do. The COVID-19 is scary because it is new and we do not know a lot about it yet. New viruses are always scary because we have little to no protective immunity against them and we do not have vaccines. There is work going on to understand and develop preventive strategies to deal with this COVID-19 threat. However, universal precautions to limit its spread are very important right now until a new vaccine or another strategy is available.

- Jeffrey A. Woods, as quoted in “Should, and how can, exercise be done during a coronavirus outbreak? An interview with Dr. Jeffrey A. Woods”, by Weimo Zhu, J Sport Health Sci. (2020 Mar Published online 2020 Feb 4); 9(2): 105–107.

- Many of Arkansas Children’s new COVID-19 patients are also much more ill than before. They’re coming in with wrecked lungs, struggling to breathe; they’re not bouncing back with typical youthful resilience, despite having been very healthy before. “This COVID surge, I’ve never seen anything like it,” Linda Young, a respiratory therapist who’s been on the job for 37 years, told me. “It’s the sickest I’ve ever seen children.” It’s become common for more than half of the kids in the ICU to be on ventilators. A few have been in the hospital for more than a month. “We are not able to discharge them as fast as they are coming,” Abdallah Dalabih, a pediatric critical-care physician, told me. Some parents, Snowden said, are in disbelief. “Many people didn’t believe kids could get this thing,” she said.

- Katherine J. Wu, “Delta Is Bad News for Kids”, The Atlantic, (August 10, 2021)

- Amid all the chaos is perhaps one tentative silver lining for children. The new variant appears to be following the long-standing trend that kids are, on average, more resistant to the coronavirus’s effects. Although Delta is a more cantankerous version of the virus than its predecessors, researchers don’t yet have evidence that it is specifically worse for children, who are still getting seriously sick only a small fraction of the time. Less than 2 percent of known pediatric COVID-19 cases, for instance, result in hospitalization, sometimes far less.

- Katherine J. Wu, “Delta Is Bad News for Kids”, The Atlantic, (August 10, 2021)

- Kids’ bodies can and do fight back, though an explanation for their tenacity remains elusive. One idea posits that kids’ airway cells might be tougher for the coronavirus to break into, Stephanie Langel, an immunologist at Duke University, told me. Another proposes that their immune system is especially adept at churning out an alarm molecule that buttresses the body against infection. Kids, Langel said, might even have a way of marshaling certain antibodies faster than adults, stamping out the virus before it has a chance to infiltrate other tissues.

- Katherine J. Wu, “Delta Is Bad News for Kids”, The Atlantic, (August 10, 2021)

- I say "possibly" (for the SARS-CoV-2 to more dangerous to humans than the other coronaviruses) because so far, not only do we not know how dangerous it is, we can't know. Outbreaks of new viral diseases are like the steel balls in a pinball machine: You can slap your flippers at them, rock the machine on its legs and bonk the balls to the jittery rings, but where they end up dropping depends on 11 levels of chance as well as on anything you do. This is true with coronaviruses in particular: They mutate often while they replicate, and can evolve as quickly as a nightmare ghoul.

- Shi Zhengli (2020) cited in "We Made the Coronavirus Epidemic" on The New York Times, 28 January 2020.

“Covid may no longer be the most 'significant' threat to health, Dr Jenny Harries says” (10 October 2021)

[edit]Danielle Sheridan, Covid may no longer be the most 'significant' threat to health, Dr Jenny Harries says, Telegraph, (10 October 2021).

- Covid may no longer be the most "significant" threat to health, Dr Jenny Harries has said.

- The chief executive of the UK Health Security Agency said today that Covid was possibly no more dangerous than flu.

“The coronavirus is mutating — does it matter?” (9/8/2020)

[edit]Ewen Callaway, “The coronavirus is mutating — does it matter?”, Nature, (08 September 2020; correction 16 September 2020), 585, pp.174-177.

- When COVID-19 spread around the globe this year, David Montefiori wondered how the deadly virus behind the pandemic might be changing as it passed from person to person. Montefiori is a virologist who has spent much of his career studying how chance mutations in HIV help it to evade the immune system. The same thing might happen with SARS-CoV-2, he thought.

In March, Montefiori, who directs an AIDS-vaccine research laboratory at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, contacted Bette Korber, an expert in HIV evolution and a long-time collaborator. Korber, a computational biologist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in New Mexico, had already started scouring thousands of coronavirus genetic sequences for mutations that might have changed the virus’s properties as it made its way around the world.

Compared with HIV, SARS-CoV-2 is changing much more slowly as it spreads. But one mutation stood out to Korber. It was in the gene encoding the spike protein, which helps virus particles to penetrate cells. Korber saw the mutation appearing again and again in samples from people with COVID-19. At the 614th amino-acid position of the spike protein, the amino acid aspartate (D, in biochemical shorthand) was regularly being replaced by glycine (G) because of a copying fault that altered a single nucleotide in the virus’s 29,903-letter RNA code. Virologists were calling it the D614G mutation.

In April, Korber, Montefiori and others warned in a preprint posted to the bioRxiv server that “D614G is increasing in frequency at an alarming rate”1. It had rapidly become the dominant SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Europe and had then taken hold in the United States, Canada and Australia. D614G represented a “more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2”, the paper declared, one that had emerged as a product of natural selection. - Viruses that encode their genome in RNA, such as SARS-CoV-2, HIV and influenza, tend to pick up mutations quickly as they are copied inside their hosts, because enzymes that copy RNA are prone to making errors. After the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus began circulating in humans, for instance, it developed a kind of mutation called a deletion that might have slowed its spread.

But sequencing data suggest that coronaviruses change more slowly than most other RNA viruses, probably because of a ‘proofreading’ enzyme that corrects potentially fatal copying mistakes. A typical SARS-CoV-2 virus accumulates only two single-letter mutations per month in its genome — a rate of change about half that of influenza and one-quarter that of HIV, says Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Basel, Switzerland.

Other genome data have emphasized this stability — more than 90,000 isolates have been sequenced and made public (see www.gisaid.org). Two SARS-CoV-2 viruses collected from anywhere in the world differ by an average of just 10 RNA letters out of 29,903, says Lucy Van Dorp, a computational geneticist at University College London, who is tracking the differences for signs that they confer an evolutionary advantage.

Despite the virus’s sluggish mutation rate, researchers have catalogued more than 12,000 mutations in SARS-CoV-2 genomes. But scientists can spot mutations faster than they can make sense of them. Many mutations will have no consequence for the virus’s ability to spread or cause disease, because they do not alter the shape of a protein, whereas those mutations that do change proteins are more likely to harm the virus than improve it (see ‘A catalogue of coronavirus mutations’). “It’s much easier to break something than it is to fix it,” says Hodcroft, who is part of Nextstrain, an effort to analyse SARS-CoV-2 genomes in real time. - Many researchers suspect that if a mutation did help the virus to spread faster, it probably happened earlier, when the virus first jumped into humans or acquired the ability to move efficiently from one person to another. At a time when nearly everyone on the planet is susceptible, there is likely to be little evolutionary pressure on the virus to spread better, so even potentially beneficial mutations might not flourish. “As far as the virus is concerned, every single person that it comes to is a good piece of meat,” says William Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. “There’s no selection to be doing it any better.”

- D614G was first spotted in viruses collected in China and Germany in late January; most scientists suspect the mutation arose in China. It’s now almost always accompanied by three mutations in other parts of the SARS-CoV-2 genome — possible evidence that most D614G viruses share a common ancestor.

D614G’s rapid rise in Europe drew Korber’s attention. Before March — when much of the continent went into lockdown — both unmutated ‘D’ viruses and mutated ‘G’ viruses were present, with D viruses prevalent in most of the western European countries that geneticists sampled at the time. In March, G viruses rose in frequency across the continent, and by April they were dominant, reported Korber, Montefiori and their team. - The first team to report pseudovirus experiments on D614G, in June, was led by Hyeryun Choe and Michael Farzan, virologists at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California5. Several other teams have posted similar studies on bioRxiv (Montefiori’s experiments, and those of another collaborator, appeared in the Cell paper2). The teams used different pseudovirus systems and tested them on various kinds of cell, but the experiments pointed to the same conclusion: viruses carrying the G mutation infected cells much more ably than did D viruses — up to ten times more efficiently, in some cases.

In laboratory tests, “all of us agree that D to G is making the particles more infectious”, says Jeremy Luban, a virologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. But these studies come with many caveats — and their relevance to human infections is unclear. “What’s irritating are people taking their results in very controlled settings, and saying this means something for the pandemic. That, we are so far away from knowing,” says Grubaugh. The pseudoviruses carry only the coronavirus spike protein, in most cases, and so the experiments measure only the ability of these particles to enter cells, not aspects of their effects inside cells, let alone on an organism. They also lack the other three mutations that almost all D614G viruses carry. “The bottom line is, they’re not the virus,” says Luban. - Some labs are now working with infectious SARS-CoV-2 viruses that differ by only the single amino acid. These are tested in laboratory cultures of human lung and airway cells, and in lab animals such as ferrets and hamsters. For labs with the experience and the biosafety capabilities to manipulate viruses, “this is like bread-and-butter kind of work”, says Sheahan. The first of those studies, led by researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, was reported in a 2 September preprint6. It found that viruses with the mutation were more infectious than were D viruses in a human lung cell line and in airway tissues, and that mutated viruses were present at greater levels in the upper airways of infected hamsters6.

Even these experiments might not offer absolute clarity. Some studies show that certain mutations to the spike protein in the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) virus can cause more-severe disease in mice — yet other mutations in the protein show very little effect in people or in camels, the likely reservoir for human MERS infections, says Stanley Perlman, a coronavirologist at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. - Grubaugh thinks that D614G has received too much attention from scientists, in part because of the high-profile papers it has garnered. “Scientists have this crazy fascination with these mutations,” he says. But he also sees D614G as a way to learn about a virus that doesn’t have much in the way of genetic diversity. “The virologist in me looks at these things and says it would be a lot of fun to study,” he says. “It creates this whole rabbit hole of different things you can go into.”

- A team led by virologists Theodora Hatziioannou and Paul Bieniasz, at Rockefeller University in New York City, genetically modified the vesicular stomatitis virus — a livestock pathogen — so that it used the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to infect cells, and grew it in the presence of neutralizing antibodies. Their goal was to select for mutations that enabled the spike protein to evade antibody recognition. The experiment generated spike-protein mutants that were resistant to antibodies taken from the blood of people who had recovered from COVID-19, as well as to potent ‘monoclonal’ antibodies that are being developed into therapies. Every one of the spike mutations was found in virus sequences isolated from patients, report Hatziioannou, Bieniasz and their team — although at very low frequencies that suggest positive selection is not yet making the mutations more common11.

Other scientists are trying to stay ahead of SARS-CoV-2’s evolution by predicting which mutations are likely to be important. Jesse Bloom, an evolutionary virologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, led a team that created nearly 4,000 mutated versions of the spike protein’s RBD, and measured how the alterations affected the expression of the spike protein and its ability to bind to ACE2. Most of the mutations had no effect on or hindered these properties, although a handful improved them. Some of these mutations have been identified in people with COVID-19, but Bloom’s team found no signs of natural selection for any of the variants. “Probably the virus binds to ACE2 about as well as it needs to right now,” he says. - Studies of common-cold coronaviruses, sampled across multiple seasons, have identified some signs of evolution in response to immunity. But the pace of change is slow, says Volker Thiel, an RNA virologist at the Institute of Virology and Immunology in Bern. “These strains remain constant, more or less.”

- With most of the world still susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, it’s unlikely that immunity is currently a major factor in the virus’s evolution. But as population-wide immunity rises, whether through infection or vaccination, a steady trickle of immune-evading mutations could help SARS-CoV-2 to establish itself permanently, says Sheahan, potentially causing mostly mild symptoms when it infects individuals who have some residual immunity from a previous infection or vaccination. “I wouldn’t be surprised if this virus is maintained as a more common, cold-causing coronavirus.” But it’s also possible that our immune responses to coronavirus infections, including to SARS-CoV-2, aren’t strong or long-lived enough to generate selection pressure that leads to significantly altered virus strains.

Worrisome mutations could also become more common if antibody therapies aren’t used wisely — if people with COVID-19 receive one antibody, which could be thwarted by a single viral mutation, for example. Cocktails of monoclonal antibodies, each of which can recognize multiple regions of the spike protein, might lessen the odds that such a mutation will be favoured through natural selection, researchers say. Vaccines arouse less concern on this score because, like the body’s natural immune response, they tend to elicit a range of antibodies.

“Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19”

[edit]CDC, “Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19”

- COVID-19 seems to spread more easily than flu and causes more serious illnesses in some people. It can also take longer before people show symptoms and people can be contagious for longer.

- Because some of the symptoms of flu and COVID-19 are similar, it may be hard to tell the difference between them based on symptoms alone, and testing may be needed to help confirm a diagnosis.

- COVID-19 seems to cause more serious illnesses in some people. Other signs and symptoms of COVID-19, different from flu, may include change in or loss of taste or smell.

- While COVID-19 and flu viruses are thought to spread in similar ways, COVID-19 is more contagious among certain populations and age groups than flu. Also, COVID-19 has been observed to have more superspreading events than flu.

“Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic” (04 May 2020)

[edit]David Cyranoski, “Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic”, Nature, (04 May 2020), 581, pp.22-26

These differences have led to some confusion about the lethality of SARS-CoV-2. Some experts and media reports describe it as less deadly than SARS-CoV because it kills about 1% of the people it infects, whereas SARS-CoV killed at roughly ten times that rate. But Perlman says that’s the wrong way to look at it. SARS-CoV-2 is much better at infecting people, but many of the infections don’t progress to the lungs. “Once it gets down in the lungs, it’s probably just as deadly,” he says.

Rambaut, too, doubts that the virus will become milder over time and spare its host. “It doesn’t work that way,” he says. As long as it can successfully infect new cells, reproduce and transmit to new ones, it doesn’t matter whether it harms the host, he says.

- In 1912, German veterinarians puzzled over the case of a feverish cat with an enormously swollen belly. That is now thought to be the first reported example of the debilitating power of a coronavirus. Veterinarians didn’t know it at the time, but coronaviruses were also giving chickens bronchitis, and pigs an intestinal disease that killed almost every piglet under two weeks old.

The link between these pathogens remained hidden until the 1960s, when researchers in the United Kingdom and the United States isolated two viruses with crown-like structures causing common colds in humans. Scientists soon noticed that the viruses identified in sick animals had the same bristly structure, studded with spiky protein protrusions. Under electron microscopes, these viruses resembled the solar corona, which led researchers in 1968 to coin the term coronaviruses for the entire group.

It was a family of dynamic killers: dog coronaviruses could harm cats, the cat coronavirus could ravage pig intestines. Researchers thought that coronaviruses caused only mild symptoms in humans, until the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 revealed how easily these versatile viruses could kill people. - Of the viruses that attack humans, coronaviruses are big. At 125 nanometres in diameter, they are also relatively large for the viruses that use RNA to replicate, the group that accounts for most newly emerging diseases. But coronaviruses really stand out for their genomes. With 30,000 genetic bases, coronaviruses have the largest genomes of all RNA viruses. Their genomes are more than three times as big as those of HIV and hepatitis C, and more than twice influenza’s.

Coronaviruses are also one of the few RNA viruses with a genomic proofreading mechanism — which keeps the virus from accumulating mutations that could weaken it. That ability might be why common antivirals such as ribavirin, which can thwart viruses such as hepatitis C, have failed to subdue SARS-CoV-2. The drugs weaken viruses by inducing mutations. But in the coronaviruses, the proofreader can weed out those changes.

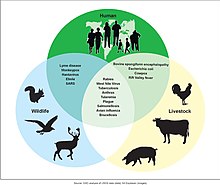

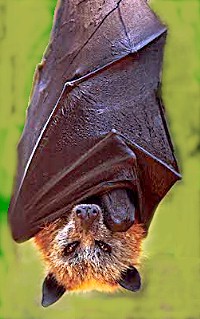

Mutations can have their advantages for viruses. Influenza mutates up to three times more often than coronaviruses do, a pace that enables it to evolve quickly and sidestep vaccines. But coronaviruses have a special trick that gives them a deadly dynamism: they frequently recombine, swapping chunks of their RNA with other coronaviruses. Typically, this is a meaningless trading of like parts between like viruses. But when two distant coronavirus relatives end up in the same cell, recombination can lead to formidable versions that infect new cell types and jump to other species, says Rambaut. - Estimates for the birth of the first coronavirus vary widely, from 10,000 years ago to 300 million years ago. Scientists are now aware of dozens of strains3, seven of which infect humans. Among the four that cause common colds, two (OC43 and HKU1) came from rodents, and the other two (229E and NL63) from bats. The three that cause severe disease — SARS-CoV (the cause of SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 — all came from bats. But scientists think there is usually an intermediary — an animal infected by the bats that carries the virus into humans. With SARS, the intermediary is thought to be civet cats, which are sold in live-animal markets in China.

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 is still an open question (see ‘Family of killers’). The virus shares 96% of its genetic material with a virus found in a bat in a cave in Yunnan, China4 — a convincing argument that it came from bats, say researchers. But there’s a crucial difference. The spike proteins of coronaviruses have a unit called a receptor-binding domain, which is central to their success in entering human cells. The SARS-CoV-2 binding domain is particularly efficient, and it differs in important ways from that of the Yunnan bat virus, which seems not to infect people5.

Complicating matters, a scaly anteater called the pangolin showed up with a coronavirus that had a receptor-binding domain almost identical to the human version. But the rest of the coronavirus was only 90% genetically similar, so some researchers suspect the pangolin was not the intermediary5. The fact that both mutations and recombinations are at work complicates efforts to draw a family tree. - Although the known human coronaviruses can infect many cell types, they all mainly cause respiratory infections. The difference is that the four that cause common colds easily attack the upper respiratory tract, whereas MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV have more difficulty gaining a hold there, but are more successful at infecting cells in the lungs.

SARS-CoV-2, unfortunately, can do both very efficiently. That gives it two places to get a foothold, says Shu-Yuan Xiao, a pathologist at the University of Chicago, Illinois. A neighbour’s cough that sends ten viral particles your way might be enough to start an infection in your throat, but the hair-like cilia found there are likely to do their job and clear the invaders. If the neighbour is closer and coughs 100 particles towards you, the virus might be able get all the way down to the lungs, says Xiao.

These varying capacities might explain why people with COVID-19 have such different experiences. The virus can start in the throat or nose, producing a cough and disrupting taste and smell, and then end there. Or it might work its way down to the lungs and debilitate that organ. How it gets down there, whether it moves cell by cell or somehow gets washed down, is not known, says Stanley Perlman, an immunologist at the University of Iowa in Iowa City who studies coronaviruses. - Clemens-Martin Wendtner, an infectious-disease physician at the Munich Clinic Schwabing in Germany, says it could be a problem with the immune system that lets the virus sneak down into the lungs. Most infected people create neutralizing antibodies that are tailored by the immune system to bind with the virus and block it from entering a cell. But some people seem unable to make them, says Wendtner. That might be why some recover after a week of mild symptoms, whereas others get hit with late-onset lung disease. But the virus can also bypass the throat cells and go straight down into the lungs. Then patients might get pneumonia without the usual mild symptoms such as a cough or low-grade fever that would otherwise come first, says Wendtner. Having these two infection points means that SARS-CoV-2 can mix the transmissibility of the common cold coronaviruses with the lethality of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. “It is an unfortunate and dangerous combination of this coronavirus strain,” he says.

- The virus’s ability to infect and actively reproduce in the upper respiratory tract was something of a surprise, given that its close genetic relative, SARS-CoV, lacks that ability. Last month, Wendtner published results8 of experiments in which his team was able to culture virus from the throats of nine people with COVID-19, showing that the virus is actively reproducing and infectious there. That explains a crucial difference between the close relatives. SARS-CoV-2 can shed viral particles from the throat into saliva even before symptoms start, and these can then pass easily from person to person. SARS-CoV was much less effective at making that jump, passing only when symptoms were full-blown, making it easier to contain.

These differences have led to some confusion about the lethality of SARS-CoV-2. Some experts and media reports describe it as less deadly than SARS-CoV because it kills about 1% of the people it infects, whereas SARS-CoV killed at roughly ten times that rate. But Perlman says that’s the wrong way to look at it. SARS-CoV-2 is much better at infecting people, but many of the infections don’t progress to the lungs. “Once it gets down in the lungs, it’s probably just as deadly,” he says. - What it does when it gets down to the lungs is similar in some respects to what respiratory viruses do, although much remains unknown. Like SARS-CoV and influenza, it infects and destroys the alveoli, the tiny sacs in the lungs that shuttle oxygen into the bloodstream. As the cellular barrier dividing these sacs from blood vessels break down, liquid from the vessels leaks in, blocking oxygen from getting to the blood. Other cells, including white blood cells, plug up the airway further. A robust immune response will clear all this out in some patients, but overreaction of the immune system can make the tissue damage worse. If the inflammation and tissue damage are too severe, the lungs never recover and the person dies or is left with scarred lungs, says Xiao. “From a pathological point of view, we don’t see a lot of uniqueness here.”

And as with SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and animal coronaviruses, the damage doesn’t stop with the lungs. A SARS-CoV-2 infection can trigger an excessive immune response known as a cytokine storm, which can lead to multiple organ failure and death. The virus can also infect the intestines, the heart, the blood, sperm (as can MERS-CoV), the eye and possibly the brain. Damage to the kidney, liver and spleen observed in people with COVID-19 suggests that the virus can be carried in the blood and infect various organs or tissues, says Guan Wei-jie, a pulmonologist at the Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health at Guangzhou Medical University, China, an institution lauded for its role in combating SARS and COVID-19. The virus might be able to infect various organs or tissues wherever the blood supply reaches, says Guan.

But although genetic material from the virus is showing up in these various tissues, it is not yet clear whether the damage there is being done by the virus or by a cytokine storm, says Wendtner. “Autopsies are under way in our centre. More data will come soon,” he says. - SARS-CoV-2 is uniquely equipped for forcing entry into cells. Both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 bind with ACE2, but the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 is a particularly snug fit. It is 10–20 times more likely to bind ACE2 than is SARS-CoV9. Wendtner says that SARS-CoV-2 is so good at infecting the upper respiratory tract that there might even be a second receptor that the virus could use to launch its attack.

- Scientists think that the involvement of furin could explain why SARS-CoV-2 is so good at jumping from cell to cell, person to person and possibly animal to human. Robert Garry, a virologist at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, estimates that it gives SARS-CoV-2 a 100–1,000 times greater chance than SARS-CoV of getting deep into the lungs. “When I saw SARS-CoV-2 had that cleavage site, I did not sleep very well that night,” he says.

The mystery is where the genetic instructions for this particular cleavage site came from. Although the virus probably gained them through recombination, this particular set-up has never been found in any other coronavirus in any species. Pinning down its origin might be the last piece in the puzzle that will determine which animal was the stepping stone that allowed the virus to reach humans. - Some researchers hope that the virus will weaken over time through a series of mutations that adapt it to persist in humans. By this logic, it would become less deadly and have more chances to spread. But researchers have not yet found any sign of such weakening, probably because of the virus’s efficient genetic repair mechanism. “The genome of COVID-19 virus is very stable, and I don’t see any change of pathogenicity that is caused by virus mutation,” says Guo Deyin, who researches coronaviruses at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou.

Rambaut, too, doubts that the virus will become milder over time and spare its host. “It doesn’t work that way,” he says. As long as it can successfully infect new cells, reproduce and transmit to new ones, it doesn’t matter whether it harms the host, he says.

But others think there is a chance for a better outcome. It might give people antibodies that will offer at least partial protection, says Klaus Stöhr, who headed the World Health Organization’s SARS research and epidemiology division. Stöhr says that immunity will not be perfect — people who are reinfected will still develop minor symptoms, the way they do now from the common cold, and there will be rare examples of severe disease. But the virus’s proofreading mechanism means it will not mutate quickly, and people who were infected will retain robust protection, he says.

“By far the most likely scenario is that the virus will continue to spread and infect most of the world population in a relatively short period of time,” says Stöhr, meaning one to two years. “Afterwards, the virus will continue to spread in the human population, likely forever.” Like the four generally mild human coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 would then circulate constantly and cause mainly mild upper respiratory tract infections, says Stöhr. For that reason, he adds, vaccines won’t be necessary. - The OC43 coronavirus offers a model for where this pandemic might go. That virus also gives humans common colds, but genetic research from the University of Leuven in Belgium suggests that OC43 might have been a killer in the past11. That study indicates that OC43 spilled over to humans in around 1890 from cows, which got it from mice. The scientists suggest that OC43 was responsible for a pandemic that killed more than one million people worldwide in 1889–90 — an outbreak previously blamed on influenza. Today, OC43 continues to circulate widely and it might be that continual exposure to the virus keeps the great majority of people immune to it.

- Many scientists are reserving judgement on whether the tamer coronaviruses were once as virulent as SARS-CoV-2. People like to think that “the other coronaviruses were terrible and became mild”, says Perlman. “That’s an optimistic way to think about what’s going on now, but we don’t have evidence.”

“Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne — but health advice has not caught up” (08/07/2020)

[edit]Dyani Lewis, “Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne — but health advice has not caught up”, Nature, (08 July 2020; update 23 July 2020), 583, pp.510-513.

- On 6 July, Morawska and aerosol scientist Donald Milton at the University of Maryland, College Park, supported by an international group of 237 other clinicians, infectious-disease physicians, epidemiologists, engineers and aerosol scientists, published a commentary in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases that urges the medical community and public-health authorities to acknowledge the potential for airborne transmission. They also call for preventive measures to reduce this type of risk.

The researchers are frustrated that key agencies, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), haven’t been heeding their advice in their public messages.

In response to the commentary, the WHO softened its position. At a 7 July press conference, Benedetta Allegranzi, technical leader of the WHO task force on infection control said: “We have to be open to this evidence and understand its implications regarding the modes of transmission, and also regarding the precautions that need to be taken.”

On 9 July, the WHO issued a scientific brief on viral transmission. It maintains that more research is needed “given the possible implications of such [a] route of transmission”, but acknowledges that short-range aerosol transmission cannot be ruled out in crowded, poorly ventilated spaces. (The WHO told Nature that it had been working on this brief for a month, and that it was not a result of the commentary.) - For months, the WHO had steadfastly pushed back against the idea that there is a significant threat of the coronavirus being transmitted by aerosols that can accumulate in poorly ventilated venues and be carried on air currents. The agency maintains that the virus is spread mainly by contaminated surfaces and by droplets bigger than aerosols that are generated by coughing, sneezing and talking. These are thought to travel relatively short distances and drop quickly from the air.

This type of guidance has hampered efforts that could prevent airborne transmission, such as measures that improve ventilation of indoor spaces and limits on indoor gatherings, say the researchers in the commentary: “We are concerned that the lack of recognition of the risk of airborne transmission of COVID-19 and the lack of clear recommendations on the control measures against the airborne virus will have significant consequences: people may think that they are fully protected by adhering to the current recommendations, but in fact, additional airborne interventions are needed for further reduction of infection risk.” - Since the 1930s, public-health researchers and officials have generally discounted the importance of aerosols — droplets less than 5 micrometres in diameter — in respiratory diseases such as influenza. Instead, the dominant view is that respiratory viruses are transmitted by the larger droplets, or through contact with droplets that fall on surfaces or are transferred by people’s hands. When SARS-CoV-2 emerged at the end of 2019, the assumption was that it spread in the same way as other respiratory viruses and that airborne transmission was not important.

The WHO is following the available evidence, and has moderated its earlier opposition to the idea that the virus might spread through aerosols, Allegranzi says. She says that although the WHO acknowledges that airborne transmission is plausible, current evidence falls short of proving the case. She adds that recommendations for physical distancing, quarantine and wearing masks in the community are likely to go some way towards controlling aerosol transmission if it is occurring. - When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, health officials recommended frequent hand washing and maintaining a physical distance to break droplet and contact transmission routes. And some researchers and clinicians say these approaches are enough. Contact-tracing data support those measures, says Kate Grabowski, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “The highest-risk contacts are those that are individuals you share a home with or that you’ve been in a confined space with for a substantial period of time, which would lead me to believe it’s probably driven mostly by droplet transmission,” she says, although she says that aerosol transmission might occur on rare occasions.

But other researchers say that case studies of large-scale clusters have shown the importance of airborne transmission. When the news media reported large numbers of people falling ill following indoor gatherings, that caused Kim Prather, an aerosol scientist at the University of California, San Diego, to begin questioning the adequacy of the social-distancing recommendations from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which call for people to stay 6 feet (1.8 metres) apart. The indoor spread suggested the virus was being transmitted in a different way from how health authorities had assumed. “For an atmospheric chemist, which I am, the only way you get there is you put it in the air and everybody breathes that air,” says Prather, who joined the commentary. “That is the smoking gun.” - Laboratory studies going back to the 1930s and 1940s concluded that droplets expelled through talking or coughing are larger than aerosols. These bigger droplets, more than 5 micrometres in diameter, drop out of the air quickly because they are too heavy to ride on light air currents.

But more-sensitive experiments are now painting a more complex picture that points to the importance of aerosols as a transmission route. A study published in May used laser-light scattering to detect droplets emitted by healthy volunteers when speaking. The authors calculated6 that for SARS-CoV-2, one minute of loud speaking generates upwards of 1,000 small, virus-laden aerosols 4 micrometres in diameter that remain airborne for at least 8 minutes. They conclude that “there is a substantial probability that normal speaking causes airborne virus transmission in confined environments”.

Another study7 published by Morawska and her colleagues as a preprint, which has not yet been peer reviewed, found that people infected with SARS-CoV-2 exhaled 1,000–100,000 copies per minute of viral RNA, a marker of the pathogen’s presence. Because the volunteers simply breathed out, the viral RNA was probably carried in aerosols rather than in the large droplets produced during coughing, sneezing or speaking. - One of the problems researchers face in studying virus viability in aerosols is the way that samples are collected. Typical devices that suck in air samples damage a virus’s delicate lipid envelope, says Julian Tang, a virologist at the University of Leicester, UK. “The lipid envelope will shear, and then we try and culture those viruses and get very, very low recovery,” he says.

- A few studies, however, have successfully measured the viability of aerosol-borne virus particles. A team at the US Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate in Washington DC found that environmental conditions play a big part in how long virus particles in aerosols remain viable. SARS-CoV-2 in mock saliva aerosols lost 90% of its viability in 6 minutes of exposure to summer sunlight, compared with 125 minutes in darkness10. This study suggests that indoor environments might be especially risky, because they lack ultraviolet light and because the virus can become more concentrated than it would be in outdoor spaces.

- Tang, who contributed to the commentary, says the bar of proof is too high regarding airborne transmission. “[The WHO] ask for proof to show it’s airborne, knowing that it’s very hard to get proof that it’s airborne,” he says. “In fact, the airborne-transmission evidence is so good now, it’s much better than contact or droplet evidence for which they’re saying wash [your] hands to everybody.”

Ultimately, says Morawska, strong action from the top is crucial. “Once the WHO says it’s airborne, then all the national bodies will follow,” she says. - Governments have started to move on their own to combat airborne transmission. In May, the guidance from the German department of health changed to state explicitly that “Studies indicate that the novel coronavirus can also be transmitted through aerosols … These droplet nuclei can remain suspended in the air over longer periods of time and may potentially transmit viruses. Rooms containing several people should therefore be ventilated regularly.” The CDC doesn’t mention aerosols or airborne transmission, but it updated its website on 16 June to say that the closeness of contact and the duration of exposure are important.

A spokesperson for the United Kingdom’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies says there is weak evidence for aerosol transmission in some situations, but the group nonetheless recommends “that measures to control transmission include those that target aerosol routes”. When the United Kingdom reviewed its social-distancing guidelines, it advised people to take extra precautions in situations where it isn’t possible to stay 2 metres apart. The advice includes recommendations to wear a face mask and to avoid face-to-face interactions, poor ventilation and loud talking or singing. - This is not the first time during the pandemic that clinicians and researchers have criticized the WHO for being slow to update guidelines. Many had called on the agency early on to acknowledge that face masks can help to protect the general public. But the WHO did not make an announcement on this until 5 June, when it changed its stance and recommended the wearing of cloth masks when social distancing wasn’t possible, such as on public transport and in shops. Many countries were already recommending or mandating their use. On 3 April, the CDC issued recommendations to use masks in areas where transmission rates are high. And evidence backs up those actions: a systematic review found ten studies of COVID-19 and related coronaviruses — predominantly in health-care settings — that together show that face masks do reduce the risk of infection11.

Allegranzi acknowledges that, regarding the WHO’s position on masks, “the previous [advice] maybe was less clear or more cautious”. She says that emerging evidence that a person with SARS-CoV-2 is able to pass it on before symptoms have started (pre-symptomatic) or without ever showing symptoms (asymptomatic), factored into the decision to change the guidance. Other research — commissioned by the WHO — showing that cloth face masks are an effective barrier, was also an important factor.

“COVID-19 rarely spreads through surfaces. So why are we still deep cleaning?” (29/1/2021)

[edit]Dyani Lewis, “COVID-19 rarely spreads through surfaces. So why are we still deep cleaning?”, Nature, (29 January 2021), 590, pp.26-28

- The focus on fomites — rather than aerosols — emerged at the very beginning of the coronavirus outbreak because of what people knew about other infectious diseases. In hospitals, pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, respiratory syncytial virus and norovirus can cling to bed rails or hitch a ride from one person to the next on a doctor’s stethoscope. So as soon as people started falling ill from the coronavirus, researchers began swabbing hospital rooms and quarantine facilities for places the virus could be lurking. And it seemed to be everywhere.

In medical facilities, personal items such as reading glasses and water bottles tested positive for traces of viral RNA — the main way that researchers identify viral contamination. So, too, did bed rails and air vents. In quarantined households, wash basins and showers harboured the RNA, and in restaurants, wooden chopsticks were found to be contaminated. And early studies suggested that contamination could linger for weeks. Seventeen days after the Diamond Princess cruise ship was vacated, scientists found3 viral RNA on surfaces in cabins of the 712 passengers and crew members who tested positive for COVID-19.

But contamination with viral RNA is not necessarily cause for alarm, says Goldman. “The viral RNA is the equivalent of the corpse of the virus,” he says. “It’s not infectious.” - Human exposure studies of other pathogens provide additional clues about fomite transmission of respiratory viruses. In 1987, researchers at the University of Wisconsin— Madison put healthy volunteers in a room to play cards with people infected with a common-cold rhinovirus. When the healthy volunteers had their arms restrained to stop them touching their faces and prevent them transferring the virus from contaminated surfaces, half became infected. A similar number of volunteers who were unrestrained also became infected. In a separate experiment, cards and poker chips that had been handled and coughed on by sick volunteers were taken to a separate room, where healthy volunteers were instructed to play poker while rubbing their eyes and noses. The only possible mode of transmission was through the contaminated cards and chips; none became infected. The combination of experiments provided strong evidence that rhinoviruses spread through the air. But such studies are considered unethical for SARS-CoV-2, because it can kill.

- The WHO updated its guidance on 20 October, saying that the virus can spread “after infected people sneeze, cough on, or touch surfaces, or objects, such as tables, doorknobs and handrails”. A WHO spokesperson told Nature that “there is limited evidence of transmission through fomites. Nonetheless, fomite transmission is considered a possible mode of transmission, given consistent finding of environmental con tamination, with positive identification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the vicinity of people infected with SARS-CoV-2.” The WHO adds that “disinfection practices are important to reduce the potential for COVID-19 virus contamination”.

“Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it” (2/23/2021)

[edit]Dyani Lewis, “Superspreading drives the COVID pandemic — and could help to tame it”, Nature, (23 February 2021), 590, pp.544-546

- With a year’s worth of data, researchers have amassed ample evidence of some chief ingredients of superspreading events: prolonged indoor gatherings with poor ventilation. Activities such as singing and aerobic exercise, which produce many of the tiny infectious droplets that can be inhaled by others, are also common components.

But key questions remain. “We have some ideas of what factors are involved, but we still don’t know what is the main driver of the superspreading,” says Endo. Foremost are uncertainties about how much individual differences in people’s behaviour and biology matter — or can be controlled — and how best to target high-risk settings while keeping the cogs of society turning. Understanding the underlying factors that drive superspreading is crucial, says Lucy Li, an infectious-diseases modeller at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub in San Francisco, California. - A team led by Bronwyn MacInnis, a geneticist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, traced the impact of superspreading events using viral genome sequences. One superspreading event — a two-day international business conference held in Boston in late February 2020 — seeded more than 90 cases in attendees and their close contacts. But the true impact was much greater, says MacInnis. She estimates that roughly 20,000 infections in Boston and its surrounding areas could be traced back to the conference.

- In all of the cases Prentiss and her team looked at, the person most likely to have infected others was either mildly symptomatic or hadn’t yet developed symptoms. This is a key similarity between the events and is probably shared by other occurrences of superspreading. “It’s transmission in young, healthy, mobile populations that actually does the most damage,” says MacInnis. “Just because you feel well doesn’t mean that you’re not infected and potentially spreading,” she says.

- Pay attention to personal hygiene. Yes, we know you’ve heard all this a million times already. It bears repeating. There are a lot of things we don’t know about this virus, but we do know it spreads through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Other individuals may be infected when they touch a surface that has virus particles on it and then touch their own mouth, nose, or eyes. Hand hygiene is the very best weapon in any fight between human and contagious disease.

- Don’t touch your face. This is a lot harder than it sounds and requires conscious effort. The average person touches their face 23 times an hour, and about half of the time, they’re touching their mouth, eyes, or nose — the mucosal surfaces that COVID-19 infects.

- Practice “social distancing.” Social distancing is exactly what it sounds like: keeping your distance from other people. It’s often used to describe public health measures imposed by local governments — measures like quarantining the sick, closing schools, and canceling public gatherings. And, when it’s done early enough during a pandemic illness, it’s been shown to save lives

“FAQ: COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019)”, “MIT.edu”.

[edit]- COVID-19 is the same type of coronavirus as MERS and SARs, both of which originated in bats. Many of the first people to contract COVID-19 in Wuhan either worked or frequently shopped at a large seafood and live-animal market, suggesting animal-to-person spread.

- February 29, 2020

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the virus is thought to spread mainly between people who are in close contact with each other (within 6 feet). The virus spreads through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. These droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby or may be inhaled into the lungs.

It may also be possible to get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching your own mouth, nose, or eyes. However, scientists do not believe this is the main way the virus spreads. To minimize the possibility of contracting the virus in this way, the CDC recommends frequent hand-washing with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand rub. The CDC also recommends routine cleaning of frequently touched surfaces.- April 7, 2020

- While we are still learning more about the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there is no evidence to support transmission of COVID-19 associated with food.