George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

Appearance

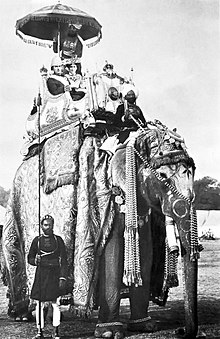

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as The Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and as The Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman who was Viceroy of India and Foreign Secretary, but who was passed over as Prime Minister in 1923 in favour of Stanley Baldwin. The Curzon Line was named after him.

Quotes

[edit]1870s

[edit]- When the figure of Lord Beaconsfield vanishes from the House of Lords and when that of Mr. Gladstone ceases to rise from the front bench on either side of the table in the House of Commons—the country will confess that its two greatest and only Statesmen have gone. Parliament will go on as before, public business will be transacted, speeches made, policies challenged and vindicated, Budgets expounded, Motions brought forward, passed, rejected, but the pre-eminent importance attaching to the doings and sayings of a Statesman will be wanting—and men will lament the degeneracy of the age.

- Paper read at the Canning Club (18 February 1879), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 103

1880s

[edit]- They had heard about the barbarities of the crowbar, and the smoking thatch; but, in his opinion, there were worse barbarities still—namely, those of the loaded gun, the mutilated animals, and the murdered women and men. Irish Members raised a great clamour about the former; but through the latter they sat as silent as stones. Nothing showed more clearly the hollowness of this agitation than the conduct of hon. Members now and their former attitude. In face of this Plan of Campaign, which had been so cleverly organized, was it not permissible that Conservative Members should have their Plan of Campaign also?

- Maiden speech in the House of Commons (31 January 1887)

- The strength and omnipotence of England everywhere in the East is amazing. No other country or people is to be compared with her. We control everything, and are liked as well as respected and feared.

- Letter to his father from Singapore (1887), quoted in Kenneth Rose, Superior Person: A Portrait of Curzon and his Circle in late Victorian England (1969), p. 202

- The Taj is incomparable, designed like a palace and finished like a jewel—a snow-white emanation starting from a bed of cypresses and backed by a turquoise sky, pure, perfect and unutterably lovely. One feels the same sensation as in gazing at a beautiful woman, one who has that mixture of loveliness and sadness which is essential to the highest beauty.

- Letter to St John Brodrick (1 January 1888), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 64

- Whatever be Russia's designs upon India, whether they be serious and inimical or imaginary and fantastic, I hold that the first duty of English statesmen is to render any hostile intentions futile, to see that our own position is secure, and our frontier impregnable, and so to guard what is without doubt the noblest trophy of British genius, and the most splendid appanage of the Imperial Crown.

- Russia in Central Asia in 1889 and the Anglo-Russian Question (1889), pp. 13-14

1890s

[edit]- Oh! it has been an amazing tour; all new; Korea, Peking, Tonking, Annam, Cochin China, Cambogia; visits to fading oriental courts; audiences with dragon-robed emperors and kings; long hard rides all the day; vile, sleepless, comfortless nights; excursions by sea boat, by river boat, on horseback, pony back and elephant back; in chairs, hammocks and palanquins.

- Letter to Miss Leiter (14 January 1893), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 191

- I have just been up in the interior of Siam to some amazing ruins, the finest in the world. It is a place called Angkor, and there a race that has since perished came some 1,700 years ago from India, founded a mighty empire and built palaces and temples that rival those of Nineveh or Karnak. Now they are buried in a tropical forest, and one has to cut a path with a billhook to see their ruins

- Letter to Miss Leiter (14 January 1893), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 192

- Rightly or wrongly, it appears to me that the continued existence of this country is bound up in the maintenance—aye I will go further and say even in the extension of the British Empire.

- Speech in Southport (15 March 1893), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 192

- It is only when you get to see and realise what India is—that she is the strength and the greatness of England—it is only then that you feel that every nerve a man may strain, every energy he may put forward, cannot be devoted to a nobler purpose than keeping tight the cords that hold India to ourselves.

- Speech in Southport (15 March 1893), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, K.G. (1928), p. 193

Persia and the Persian Question (1892)

[edit]- Above all we must remember that the ways of Orientals are not our ways, nor their thoughts our thoughts. Often when we think them backward and stupid, they think us meddlesome and absurd. The loom of time moves slowly with them, and they care not for high pressure and the roaring of the wheels. Our system may be good for us; but it is neither equally, nor altogether good for them. Satan found it better to reign in hell than to serve in heaven: and the normal Asiatic would sooner be misgoverned by Asiatics than well governed by Europeans.

- Vol. II, pp. 630-631

- The Persian character presents many complex features, elsewhere rarely united in the same individual. They are an amiable and a polished race, and have the manners of gentlemen. They are vivacious in temperament, intelligent in conversation, and acute in conduct. If their hearts are soft, which is, I believe, undeniable, there is no corresponding weakness of the head. On the other hand, they are consummate hypocrites, very corrupt, and lamentably deficient in stability or courage... Whilst, as individuals, they present many attractive features, as a community they are wholly wanting in elements of real nobility or grandeur. With one gift only can they be credited on a truly heroic scale; and this, though it may endear them to the student of human nature as a fine art, will excite the stern repugnance of the moralist. I allude to their faculty for what a Puritan might call mendacious, but what I prefer to style imaginative, utterance. This is inconceivable and enormous.

- Vol. II, p. 632

- I am convinced that a true son of Iran would sooner lie than tell the truth; and that he feels twinges of desperate remorse when, upon occasions, he has thoughtlessly strayed into veracity. Yet they are an agreeable people—agreeable to encounter, agreeable to associate with; perhaps not least agreeable to leave behind. From this composite presentment it is perhaps difficult to extract any really reliable basis of sanguine prognostication. Nevertheless there remain three attributes of the Persian character which lead me to think that that people are not yet, as has been asserted, wholly 'played out'; that they are neither sunk in the sombre atrophy of the Turk, nor threatened with the ignoble doom of the Tartar; but that there are chances of a possible redemption. These are their irrepressible vitality; an imitativeness long notorious in the East, and capable of honourable utilisation; and, in spite of occasional testimony to the contrary, a healthy freedom from deep-seated prejudice or bigotry. History suggests that the Persians will insist upon surviving themselves; present indications that they will gradually absorb the accomplishments of others.

- Vol. II, p. 633

- I have said that the people are shamefully ill-educated. I have shown that they live in an atmosphere of corruption. Civilisation will not be popular until it is taught in the schools. Respect for law, regard for contract, or faith in honesty will not be generated until the institutions by which they can be safeguarded have been called into being. This will be a work of time; but in due time it will come.

- Vol. II, p. 634

Problems of the Far East: Japan–Korea–China (1894)

[edit]- Such is the street life of Peking, a phantasmagoria of excruciating incident, too bewildering to grasp, too aggressive to acquiesce in, too absorbing to escape.

- p. 253

- Placed at a maritime coign of vantage upon the flank of Asia, precisely analogous to that occupied by Great Britain on the flank of Europe, exercising a powerful influence over the adjoining continent, but not necessarily involved in its responsibilities, she [Japan] sets before herself the supreme ambition of becoming, on a smaller scale, the Britain of the Far East.

- pp. 395-396

- The future of China is a problem the very inverse of that involved in the future of Japan. The one is a country intoxicated with the modern spirit, and requiring above all things the stamina to understand the shock of too sudden an upheaval of ancient ideas and plunge into the unknown. The other is a country stupefied with the pride of the past, and standing in need of the very impulse to which its neighbour too incontinently yields. Japan is eager to bury the past; China worships its embalmed and still life-like corpse. Japan wants to be reformed out of all likeness to herself. China declines to be reformed at all. She is a monstrous but mighty anachronism, defiantly planted on the fringe of a world to whose contact she is indifferent and whose influence she abhors; much as the stones of Solomon's Temple look down upon an alley in modern Jerusalem, or as the Column of Trajan rears its head in the heart of nineteenth-century Rome.

- p. 399

1900s

[edit]- I regarded the conservation of ancient monuments as one of the primary obligations of Government. We have a duty to our forerunners, as well as to our contemporaries and to our descendants,—nay, our duty to the two latter classes in itself demands the recognition of an obligation to the former, since we are the custodians for our own age of that which has been bequeathed to us by an earlier, and since posterity will rightly blame us if, owing to our neglect, they fail to reap the same advantages that we have been privileged to enjoy.

- Speech to the Asiatic Society of Bengal (7 February 1900), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), pp. 182-183

- If there be any one who says to me that there is no duty devolving upon a Christian Government to preserve the monuments of a pagan art or the sanctuaries of an alien faith, I cannot pause to argue with such a man. Art and beauty, and the reverence that is owing to all that has evoked human genius or has inspired human faith, are independent of creeds, and, in so far as they touch the sphere of religion, are embraced by the common religion of all mankind. Viewed from this standpoint, the rock temple of the Brahmans stands on precisely the same footing as the Buddhist Vihara, and the Mohammedan Musjid as the Christian Cathedral. There is no principle of artistic discrimination between the mausoleum of the despot and the sepulchre of the saint. What is beautiful, what is historic, what tears the mask off the face of the past and helps us to read its riddles and to look it in the eyes—these, and not the dogmas of a combative theology, are the principal criteria to which we must look.

- Speech to the Asiatic Society of Bengal (7 February 1900), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), pp. 183-184

- Every, or nearly every, successive religion that has permeated or overswept this country has vindicated its own fervour at the expense of the rival whom it had dethroned. When the Brahmans went to Ellora, they hacked away the features of all the seated Buddhas in the rock-chapels and halls. When Kutub-ud-din commenced, and Altamsh continued, the majestic mosque that flanks the Kutub Minar, it was with the spoil of Hindu temples that they reared the fabric, carefully defacing or besmearing the sculptured Jain images, as they consecrated them to their novel purpose. What part of India did not bear witness to the ruthless vandalism of the great iconoclast Aurungzeb? When we admire his great mosque with its tapering minarets, which are the chief feature of the river front at Benares, how many of us remember that he tore down the holy Hindu temple of Vishveshwar to furnish the material and to supply the site? Nadir Shah during his short Indian inroad effected a greater spoliation than has probably ever been achieved in so brief a space of time. When the Mahratta conquerors overran Northern India, they pitilessly mutilated and wantonly destroyed. When Ranjit Singh built the Golden Temple at Amritsar, he ostentatiously rifled Mohammedan buildings and mosques. Nay, dynasties did not spare their own members, nor religions their own shrines. If a capital or fort or sanctuary was not completed in the lifetime of the builder, there was small chance of its being finished, there was a very fair chance of its being despoiled, by his successor and heir. The environs of Delhi are a wilderness of deserted cities and devastated tombs. Each fresh conqueror, Hindu, or Moghul, or Pathan, marched, so to speak, to his own immortality over his predecessor's grave.

- Speech to the Asiatic Society of Bengal (7 February 1900), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), pp. 186-187

- The British Government are fortunately exempt from any such promptings, either of religious fanaticism, of restless vanity, or of dynastic and personal pride. But in proportion as they have been unassailed by such temptations, so is their responsibility the greater for inaugurating a new era and for displaying that tolerant and enlightened respect to the treasures of all which is one of the main lessons that the returning West has been able to teach to the East.

- Speech to the Asiatic Society of Bengal (7 February 1900), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), pp. 188-189

- [Duty and interest make me] an Imperialist heart and soul. Imperial expansion seems to me an inevitable necessity and carries a noble and majestic obligation. I do not see how any Englishman, contrasting India as it is with what it was or might have been, can fail to see that we came here in obedience to what I call the decree of Providence for the lasting benefit of millions of the human race. We often make great mistakes here; but I do firmly believe that there is no Government in the World that rests on so secure a moral basis, or is more fiercely animated by duty.

- Letter to John Morley (17 June 1900), quoted in S. Gopal, 'Lord Curzon and Indian Nationalism – 1898–1905', in S. N. Mukherjee (ed.), South Asian Affairs, Number Two: The Movement for National Freedom in India (1966), p. 67

- [The Indian Empire is] the biggest thing that the English are doing anywhere in the world.

- Letter to Arthur Balfour (31 March 1901), quoted in S. Gopal, 'Lord Curzon and Indian Nationalism – 1898–1905', in S. N. Mukherjee (ed.), South Asian Affairs, Number Two: The Movement for National Freedom in India (1966), p. 67

- As long as we rule India we are the greatest Power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop straight away to a third-rate Power.

- Letter to Arthur Balfour (31 March 1901), quoted in S. Gopal, 'Lord Curzon and Indian Nationalism – 1898–1905', in S. N. Mukherjee (ed.), South Asian Affairs, Number Two: The Movement for National Freedom in India (1966), p. 67

- [The Indian Empire is] the miracle of the world.

- Letter to Sir Francis Younghusband (19 September 1901), quoted in S. Gopal, 'Lord Curzon and Indian Nationalism – 1898–1905', in S. N. Mukherjee (ed.), South Asian Affairs, Number Two: The Movement for National Freedom in India (1966), p. 67

- We are ordained to walk here in the same track together for many a long day to come. You cannot do without us. We should be impotent without you. Let the Englishman and the Indian accept the consecration of a union that is so mysterious as to have in it something of the divine, and let our common ideal be a united country and a happier people.

- Speech as the Chancellor of the University of Calcutta (15 February 1902), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), p. 489

- Powerful empires existed and flourished here while Englishmen were still wandering painted in the woods, and when the British Colonies were wilderness and jungle; and India has left a deeper mark upon the history, the philosophy, and the religion of mankind than any other terrestrial unit in the universe.

- Address at the state banquet in Delhi (1 January 1903), quoted in Speeches by Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy and Governor General of India. Vol. III. 1902–1904 (1904), p. 99

- Powerful empires existed and flourished here (in India) while Englishmen were still wandering, painted, in the woods, and while the British Colonies were still a wilderness and a jungle. India has left a deeper mark upon the history, the philosophy, and the religion of mankind, than any other terrestrial unit in the universe.

- Lord Curzon, while Viceroy of India, in his address at the Great Delhi Durbar in 1901. Quoted from Avinash PAtra in "Curzon Exposed Through Avinash Patra"

- I believe that the Durbar, more than any event in modern history, showed to the Indian people the path which, under the guidance of Providence, they are treading, taught the Indian Empire its unity, and impressed the world with its moral as well as material force. It will not be forgotten. The sound of the trumpets has already died away; the captains and the kings have departed; but the effect produced by this overwhelming display of unity and patriotism is still alive and will not perish. Everywhere it is known that upon the throne of the East is seated a power that has made of the sentiments, the aspirations, and the interests of 300 millions of Asiatics a living thing, and the units in that great aggregation have learned that in their incorporation lies their strength. As a disinterested spectator of the Durbar remarked, Not until to-day did I realise that the destinies of the East still lie, as they always have done, in the hollow of India’s hand. I think, too, that the Durbar taught the lesson not only of power but of duty. There was not an officer of Government there present, there was not a Ruling Prince nor a thoughtful spectator, who must not at one moment or other have felt that participation in so great a conception carried with it responsibility as well as pride, and that he owed something in return for whatever of dignity or security or opportunity the Empire had given him.

- Budget Speech (25 March 1903), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898-1905 (1906), pp. 308-309

- I have never wavered in a strict and inflexible justice between the two races. It is the sole justification and the only stable foundation for our rule.

- Letter to Lord George Hamilton (23 September 1903), quoted in David Gilmour, Curzon: Imperial Statesman 1859–1925 (1994; 2003), p. 172

- As a pilgrim at the shrine of beauty I have visited them, but as a priest in the temple of duty have I charged myself with their reverent custody and their studious repair.

- Speech in the Legislative Council at Calcutta on the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act 1904 (18 March 1904), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), p. 198

- Since I came to India we have spent upon repairs at Agra alone a sum of between £40,000 and £50,000. Every rupee has been an offering of reverence to the past and a gift of recovered beauty to the future.

- Speech in the Legislative Council at Calcutta (18 March 1904), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), p. 199

- For where else in the world has a race gone forth and subdued, not a country or a kingdom, but a continent, and that continent peopled, not by savage tribes, but by races with traditions and a civilisation older than our own, with a history not inferior to ours in dignity or romance; subduing them not to the law of the sword, but to the rule of justice, bringing peace and order and good government to nearly one-fifth of the entire human race, and holding them with so mild a restraint that the rulers are the merest handful amongst the ruled, a tiny speck of white foam upon a dark and thunderous ocean?

- Speech in the Guildhall upon his presentation of the Freedom of the City of London (20 July 1904), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), p. 35

- If I had done nothing else in India I have written my name here, and the letters are a living joy.

- Letter to Mrs Curzon on his restoration of the Taj Mahal (4 April 1905), quoted in David Gilmour, ‘Curzon, George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011, accessed 1 Feb 2014

- It is the Indian poor, the Indian peasant, the patient, humble, silent millions, the 80 per cent who subsist by agriculture, who know very little of policies, but who profit or suffer by their results, and whom men's eyes, even the eyes of their own countrymen, too often forget—to whom I refer. He has been in the background of every policy for which I have been responsible, of every surplus of which I have assisted in the disposition. We see him not in the splendour and opulence, nor even in the squalor, of great cities; he reads no newspapers, for, as a rule, he cannot read at all; he has no politics. But he is the bone and sinew of the country, by the sweat of his brow the soil is tilled, from his labour comes one-fourth of the national income, he should be the first and the final object of every Viceroy's regard.

- Speech at the Byculla Club in Bombay two days before he departed from India (16 November 1905), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), p. 584

- To fight for the right, to abhor the imperfect, the unjust, or the mean, to swerve neither to the right hand nor to the left, to care nothing for flattery or applause or odium or abuse—it is so easy to have any of them in India—never to let your enthusiasm be soured or your courage grow dim, but to remember that the Almighty has placed your hand on the greatest of His ploughs, in whose furrow the nations of the future are germinating and taking shape, to drive the blade a little forward in your time, and to feel that somewhere among these millions you have left a little justice or happiness or prosperity, a sense of manliness or moral dignity, a spring of patriotism, a dawn of intellectual enlightenment, or a stirring of duty, where it did not before exist—that is enough, that is the Englishman's justification in India. It is good enough for his watchword while he is here, for his epitaph when he is gone. I have worked for no other aim. Let India be my judge.

- Speech at the Byculla Club in Bombay two days before he departed from India (16 November 1905), quoted in Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898–1905 (1906), pp. 589-590

- No one believes more firmly than we do that the safety and welfare of India depend on the permanence of British administration.

- Letter to Lord Minto (1907), quoted in Nicholas Mansergh, The Commonwealth Experience (1969), p. 256

1910s

[edit]- Ever since the great Civil War there has hardly been a rebellion or insurrection in any part of the world of a minority either suffering or fearing oppression which has not been encouraged by members of the Liberal Party in England. They have constituted themselves the international champions of the right of insurrection. They have made us the busybodies, and I suppose foreigners would say the political Pecksniffs, of the world. When Parliament and the Puritans rebelled against the King, when the American Colonies revolted, when the French Revolution broke out—in every case of an insurrectionary movement in the small States of Europe, whether it was Italy, or Greece, or Poland, or Hungary, or to go further afield, Armenia, or the Balkans, or the Sudan, always on the other side we have had sympathy with the minority which was rising against the majority, and we remember one case where a people were actually fighting against us, and we were told that they were persons rightly struggling to be free. Yet when Ulster proposes to do exactly the same thing, simply because it does not fit in with your policy, you accuse them of the wickedness of plunging the country into civil war.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the Irish Home Rule Bill (30 January 1913)

- In our attitude towards birds we were not far removed from a barbarian age. We allowed our boys to despoil birds' nests of their eggs; we still kept captive most beautiful objects of God's creation which were never intended for imprisonment; and we allowed gamekeepers to kill owls and also the kingfisher, the most exquisite bird that could be seen on the streams of this country, because it was supposed to devour juvenile trout. If a rare bird, a bittern or a buzzard, appeared in any neighbourhood, no effort was made for its protection. On the contrary, it was slaughtered by a local sportsman, who wrote to the local journal to boast of his "glorious" achievement.

- Speech to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in Westminster Palace Hotel (6 March 1913), quoted in The Times (7 March 1913), p. 6

- I believe that the people of this country will be very loth to condemn those whose only disloyalty it will be to have been excessive in their loyalty to the King. I do not think that the people of this country will call those "rebels" whose only form of rebellion it is to insist on remaining under the Imperial Parliament under which we all live. And depend upon it when the first blow is struck—and my argument is that it will be struck—when the first blow is struck you will kindle a flame that will rush through the country like a forest fire and will not stop until you have been consumed.

- Speech in the House of Lords on the Irish Home Rule Bill (15 July 1913)

- It seems likely that 1914 will be the most momentous year in modern British politics. For, unless a solution of the Irish problem be found that is acceptable to both parties—and this, though all favour it in the abstract, may well be found impossible—we shall be confronted with the greatest catastrophe that will have befallen the United Kingdom for 250 years—viz., the prospect of civil war. We feel that the responsibility for this disaster will rest exclusively with those who have not yet consulted the people on their Irish proposals, and decline to do so now. Our duty, the duty of every Primrose Leaguer, is clear. It is to support those who are so bravely fighting the battle of the Union in Ireland, and to insist that the last word on the Home Rule Bill shall be spoken, as it always has been spoken before, by the British democracy.

- Primrose League Gazette (31 December 1913), quoted in The Times (31 December 1913), p. 66

- The British people realise that they are fighting for the hegemony of the Empire. If necessary we shall continue the war single-handed.

- Remarks recorded in King Albert I of Belgium's diary (7 February 1916), quoted in R. van Overstraeten (ed.), The War Diaries of Albert I King of the Belgians (1954), p. 85

- I agree with you about the absurdity of shunting the Jews back into Palestine, a tiny country which has lost its fertility and only supports meagre herds of sheep and goats with occasional terraced plots of cultivation. You cannot expel the present Moslem occupation. You cannot turn the Jews into small cultivators and grazers. You cannot turn all the various sects, religion and denominations out of Jerusalem. I cannot conceive a worse bondage to which to relegate an advanced and intellectual community than to exile in Palestine.

- Letter to Edwin Montagu (8 September 1917), quoted in David Gilmour, 'The Unregarded Prophet: Lord Curzon and the Palestine Question', Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Spring 1996), p. 63

- How was it proposed to get rid of the existing majority of Mussulman inhabitants and to introduce the Jews in their place? How many would be willing to return and in what pursuits would they engage? To secure for the Jews already in Palestine equal civil and religious rights seemed to him a better policy than to aim at repatriation on a large scale. He regarded the latter as sentimental idealism, which would never be realised, and that His Majesty's Government should have nothing to do with.

- Remarks to the Cabinet (4 October 1917), quoted in David Gilmour, 'The Unregarded Prophet: Lord Curzon and the Palestine Question', Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Spring 1996), p. 64 and David Gilmour, Curzon: Imperial Statesman 1859–1925 (1994; 2003), p. 481

- In a few weeks, or at most a few months, thanks to the skill of the Allied Commanders and the bravery of their men, the objects for which we and they have endured more than four years of sacrifice and suffering have been attained. The lands upon which the enemy had laid his cruel and predatory hand are in course of being evacuated. The exiled peoples are returning in joyous crowds across the war frontiers to their homes. The military power of the enemy is broken. His resources are spent. His armaments are in course of being surrendered. Hope breathes again in the souls of the unhappy peoples whom he has trampled in the mire. The impious spirit that claimed that Might was superior to Right and that there was no law but that of successful violence in the world has been exorcised, let us hope for ever. The conflict for international honour, righteousness, and freedom has been won, and the authors of this vast and wicked conspiracy against the liberties of mankind are fugitives on the face of the earth. My Lords, this is a great hour. It has been a wonderful victory. Are we presumptuous if we see in it the judgment of a Higher Power upon panoplied arrogance and enthroned wrong?

- We may also, I think, congratulate ourselves on the part that the British Empire has played in this struggle, and on the position which it fills at the close. Among the many miscalculations of the enemy was the profound conviction, not only that we had a "contemptible little Army," but that we were a doomed and decadent nation. The trident was to be struck from our palsied grasp, the Empire was to crumble at the first shock; a nation dedicated, as we used to be told, to pleasure-taking and the pursuit of wealth was to be deprived of the place to which it had ceased to have any right, and was to be reduced to the level of a second-class, or perhaps even of a third-class Power. It is not for us in the hour of victory to boast that these predictions have been falsified; but, at least, we may say this—that the British Flag never flew over a more powerful or a more united Empire than now; Britons never had better cause to look the world in the face; never did our voice count for more in the councils of the nations, or in determining the future destinies of mankind. That that voice may be raised in the times that now lie before us in the interests of order and liberty, that that power may be wielded to secure a settlement that shall last, that that Flag may be a token of justice to others as well as of pride to ourselves, is our united hope and prayer.

1920s

[edit]- [Japan is] a restless and aggressive Power, full of energy, somewhat like the Germans in mentality, seeking in every direction to push out and find an outlet for her ambitions.

- Statement to the 1921 Imperial Conference, quoted in William Farmer Whyte, William Morris Hughes: His Life and Times (1957), p. 436

- Not even a public figure. A man of no experience. And of the utmost insignificance. The utmost insignificance.

- Reaction after Stanley Baldwin was appointed Prime Minister (22 May 1923), quoted in Harold Nicolson, Curzon: The Last Phase 1919–1925: A Study in Post-War Diplomacy (1934), p. 355

- No one is a more profound believer than myself in the policy of the Entente: and I do not rest that belief merely on the memories of the war, or on principles of self-interest; my conviction is based on the widest considerations of world peace and world progress. If France and ourselves permanently fall out, I see no prospect of the recovery of Europe or of the pacification of the world. To maintain that unity we have made innumerable sacrifices. During the last two years I have preached no other doctrine and I have pursued no other practice.

- Statement to the members of the 1923 Imperial Conference (5 October 1923), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, Volume Three (1928), p. 243

- It is not one, I think, of which we have any cause to be ashamed. We have endeavoured to exercise a steadying and moderating influence in the politics of the world, and I think and hope that we have conveyed not merely the impression, but the conviction that, whatever other Governments or countries may do, the British Government is never untrue to its word, is never disloyal to its colleagues or its allies, never does anything underhand or mean; and if this conviction be widespread, as I believe it to be, that is the real basis of the moral authority which the British Empire has long exerted and, I believe, will long continue to exert in the affairs of mankind.

- Statement to the members of the 1923 Imperial Conference (5 October 1923), quoted in The Earl of Ronaldshay, The Life of Lord Curzon: Being the Authorized Biography of George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, Volume Three (1928), p. 244

- The obstacle has been Mackenzie King, the Canadian, who is both obstinate, tiresome and stupid.

- Letter to his wife during the 1923 Imperial Conference (8 November 1923), quoted in Terry Reardon, Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King: So Similar, So Different (2012), pp. 52-53

Ibn, W. (2009). Defending the West: A critique of Edward Said's Orientalism (2009)

[edit]- "I do not see how any Englishman, contrasting India as it now is with what it was, and would certainly have been under any other conditions than British rule, can fail to see that we came and have stayed here under no blind or capricious impulse, but in obedience to what some (of whom I am one) would call the decree of Providence, others the law of destiny in any case for the lasting benefit of millions of the human race. We often make great mistakes here: we are sometimes hard, and insolent, and overbearing: we are a good deal strangled with red tape. But none the less, I do firmly believe that there is no Government in the world (and I have seen most) that rests on so secure a moral basis, or that is more freely animated by duty.""

- India was "the land not only of romance but of obligation." Curzon told members of the Bengal Chamber of Commerce at a dinner in 1903, "If I thought it were all for nothing, and that you and I ... were simply writing inscriptions on the sand to be washed out by the next tide, if I felt that we were not working here for the good of India in obedience to a higher law and to a nobler aim, then I would see the link that holds England and India together severed without a sigh. But it is because I believe in the future of this country, and in the capacity of our own race to guide it to goals that it has never hitherto attained, that I keep courage and press forward."47

- Curzon told the Asiatic Society of Bengal: If there be any one who says to me that there is no duty devolving upon a Christian Government to preserve the monuments of a pagan art, or the sanctuaries of an alien faith, I cannot pause to argue with such a man. Art and beauty, and the reverence that is owing to all that has evoked human genius or has inspired human faith, are independent of creeds, and, in so far as they touch the sphere of religion, are embraced by the common religion of all mankind.... There is no principle of artistic discrimination between the mausoleum of the despot and the sepulchre of the saint. What is beautiful, what is historic, what tears the mask off the face of the past, and helps us to read its riddles, and to look it in the eyes-these, and not the dogmas of a combative theology, are the principle criteria to which we must look.52

- "For where else in the world has a race gone forth and subdued, not a country or a kingdom, but a continent peopled, not by savage tribes, but by races with traditions and a civilisation older than our own, with a history not inferior to ours in dignity or romance; subduing them not to the law of the sword, but to the rule of justice, bringing peace and order and good government to nearly one-fifth of the entire human race, and holding them with so mild a restraint that the rulers are the merest handful against the ruled, a tiny speck of white foam upon a dark and thunderous ocean?"59

- We endeavoured to frame a plague policy which should not do violence to the instincts and sentiments of the native population; a famine policy which should profit by the experience of the past and put us in a position to cope with the next visitation when unhappily it bursts upon us; an education policy which should free the intellectual activities of the Indian people, so keen and restless as they are, from the paralysing clutch of examinations; a railway policy that will provide administratively and financially for the great extension that we believe to lie before us; an irrigation policy that will utilise to the maximum, whether remuneratively or unremuneratively, all the available water resources of India, not merely in canals.... but in tanks and reservoirs and wells; a police policy that will raise standard of the only emblem of authority that the majority of the people see, and will free then from petty diurnal tyranny and oppression.... [T]he administrator looks rather to the silent and inarticulate masses, and if he can raise, even by a little, the level of material comfort and well-being in their lives, he has earned his reward....

- We have endeavoured to render the land revenue more equable in its incidence, to lift the load of usury from the shoulders of the peasant, and to check that reckless alienation of the soil which in many parts of the country was fast converting him from a free proprietor to a bond slave. We have done our best to encourage industries which little by little will relieve the congested field of agriculture, develop the indigenous resources of India, and make that country more and more self-providing in the future. I would not indulge in any boast, but I dare to think that as a result of these efforts I can point to an India that is more prosperous, more contented, and more hopeful. Wealth is increasing in India. There is no test you can apply which does not demonstrate it. Trade is growing. Evidences of progress and prosperity are multiplying on every side.6°

- India must always remain a constellation rather than a country, a congeries of races rather than a single nation. But we are creating ties of unity among those widely diversified peoples, we are consolidating those vast and outspread territories, and, what is more important, we are going forward instead of backward. It is not a stationary, a retrograde, a downtrodden, or an impoverished India that I have been governing for the past five and a half years. Poverty there is in abundance. I defy any one to show me a great and populous city, where it does not exist. Misery and destitution there are. The question is not whether they exist, but whether they are growing more or growing less. In India, where you deal with so vast a canvas, I daresay the lights and shades of human experience are more vivid and more dramatic than elsewhere. But if you compare the India of today with the India of any previous period of history-the India of Alexander, of Asoka, of Akbar, or of Aurangzeb-you will find greater peace and tranquillity, more widely suffused comfort and contentment, superior justice and humanity, and higher standards of material well-being, than that great dependency has ever previously attained."

- "and to feel that somewhere among these millions you have left a little justice or happiness or prosperity, a sense of manliness or moral dignity, a spring of patriotism, a dawn of intellectual enlightenment, or a stirring of duty, where it did not before exist-that is enough, that is the Englishman's justification in India. It is good enough for his watchword while he is here, for his epitaph when he is gone. I have worked for no other aim. Let India be my judge."62

Undated

[edit]- [Frenchmen] are not the sort of people one would go tiger-shooting with.

- Leonard Mosley, Curzon: The End of an Epoch (1960), p. 210

Quotes about Curzon

[edit]- My name is George Nathaniel Curzon,

I am a most superior person.

My cheek is pink, my hair is sleek,

I dine at Blenheim once a week.- Written when Curzon was at Oxford, the first couplet was probably written by J. W. Mackail; the second couplet probably by Cecil Spring-Rice.

- Hardly less critical was the situation left by the Mudania armistice with Turkey. Even while the election was on Curzon had gone to Lausanne to spend nearly three months in strenuous controversy with Ismet Pasha. By sheer force of knowledge, debating ability and personality, he secured a far better peace than could have been expected. The difficult question of Mosul was postponed, and left to me to deal with more than two years later. As regard this our diplomatic and administrative position was seriously handicapped by the reckless advocates of economy at all costs in Parliament, in the Press and, not least, in a section of the Cabinet, which included Bonar Law himself, who were all for scuttle all round. Happily Curzon had charge of the Cabinet Committee which dealt with both Iraq and Palestine and, as a member of the Committee, I was greatly impressed by the sheer skill of draftsmanship which enabled him to get his way, first with his Committee and then with the Cabinet.

- Leo Amery, My Political Life, Volume Two: War and Peace 1914–1929 (1953), pp. 248-249

- [O]ne of the keys to Lord Curzon's life is to remember that his roots had struck deep into pre-industrial England, and it is from an early England that he drew the sources of his strength.

- There is no doubt that, while he has always been and always was a man whose heart and soul were for England and the Empire, yet his best friends would own that it was India and the East that held his imagination from his early youth until the end of his life. He regarded the presence of the Englishman in India as the presence of a man with a mission, and he regarded him as the servant of our country on a sacred mission. He never flinched from those high ideals and earnest endeavours, and, in spite of all, he held the scales of justice even in that great country.

- I have been collecting opinions about Curzon during my travels, and I am gradually coming to the conclusion that he is a great Viceroy. The majority of people perhaps dislike him intensely, almost always giving as their reason some childish gossip about his bad manners; but the best men I have met have been without exception his devoted admirers. They say he is a man full of courage and strenuousness, no respecter of persons, and not to be bound by red tape, but ready to take advice if there is commonsense in it, and always bent on going to the root of every matter that comes before him.

- Neville Chamberlain to Joseph Chamberlain (15 January 1905), quoted in Keith Feiling, The Life of Neville Chamberlain (1946; 1970), p. 45

- No one had ever challenged unpopularity among his own people so fearlessly as [Curzon] did in his endeavours... to secure even justice for Indians against Europeans.

- Ignatius Valentine Chirol to Lord Hardinge (12 May 1915), quoted in David Gilmour, ‘Curzon, George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011, accessed 1 Feb 2014

- "All civilization", said Lord Curzon, quoting Renan, "all civilization has been the work of aristocracies". ... It would be much more true to say "The upkeep of aristocracies has been the hard work of all civilizations".

- Winston Churchill, The People's Rights [1909] (1970), pp. 53-54

- The morning had been golden; the noontide was bronze; and the evening lead. But all were solid, and each was polished till it shone after its fashion.

- Winston Churchill, Great Contemporaries (1937), p. 288

- He was a late worker and I should think never left a paper on his table at night that he had not read.

- Duff Cooper, Old Men Forget (1953), p. 117

- I very much doubt if, since the palmy days of Mr. Gladstone, there has been any public man who combined so wide a range of interest in many subjects, and such an easy grasp of their general features, with so close and laborious attention to detail and the power of working out that detail.

- He was likewise determined to prevent famine from being used as a cause for reform. With hunger spreading on an unprecedented scale through two-thirds of the subcontinent, he ordered his officials to publicly attribute the crisis strictly to drought. When an incautious member of the Legislative Council in Calcutta, Donald Smeaton, raised the problem of over-taxation, he was (in Boer War parlance) prompdy "Stellenboshed." Although Curzons own appetite for viceregal pomp and circumstance was notorious, he lectured starving villagers that "any Government which imperilled the financial position of India in the interests of prodigal philanthropy would be open to serious criticism; but any Government which by indiscriminate alms-giving weakened the fibre and demoralised the self-reliance of the population, would be guilty of a public crime."

- Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1-85984-739-0 pg 162

- Curzon's powers of observation and analysis were extraordinary; no detail ever escaped him. His book [Persia and the Persian Question] can still be used as a topographical guide for travel in Iran.

- Cyrus Ghani, Iran and the West: A Critical Bibliography (1987), p. 88

- I have seen him so hysterical that I have felt he must go clean off his head at any moment: and I have seen him so sane and so balanced under the greatest provocation that I have felt that no one could compete with him in sanity and clarity of vision. I have seen him simple and unassuming in his manner, as jolly as a schoolboy and entirely unaffected: and I have seen him so theatrical that I have wondered whether he had not mistaken his vocation and ought not to have made a career on the stage, even as a low comedian.

- John Duncan Gregory, On the Edge of Diplomacy: Rambles and Reflections, 1902–1928 (1929), p. 251

- He was universally called pompous: but he had the most intense sense of humour, and I have even seen him turn it on himself. His irritability surpassed anything I have ever experienced in the male sex: but it must always be remembered that he was hardly ever out of pain. He suffered from absurd megalomania in regard to his knowledge of art, his worldly possessions and his social position: but I have seen him display a humility about people and things, which was almost pathetic. At all events the vision of the Marquess which will always remain the most vivid in my mind was after one deadly winter night's work—it was already 3 a.m.—when he stood with me on the steps of Carlton House Terrace, helped me into my coat and insisted on calling me a taxi himself. "I hope you won't get cold," he said, "getting home...and Chelsea is such a long way off." I never knew which made him most sorry for me, the fact that he had kept me working so late, or the fact that it was so cold, or the fact that I had the misfortune to live in such a terribly un-aristocratic suburb.

- John Duncan Gregory, On the Edge of Diplomacy: Rambles and Reflections, 1902–1928 (1929), p. 254

- Thirty-five years ago he and I were young men in London, with different outlooks, with different social surroundings, with different ideas about our careers, but an intimacy sprung up which was never checked... Three things distinguished him then, as they did later: unflinching courage, a wide devotion to the State which always looked beyond himself, and an unshakable resolution when he had made up his mind. With these qualities Lord Curzon went to India as Viceroy. It is not necessary to agree about everything in his policy in order to appreciate how great an administrator Lord Curzon was there... I know, not by his testimony but by the testimony of others, that by his courage and his determination to see justice done he redressed many an individual evil and put right much that a man of less energy and tenacity of purpose than himself could not have put right... He was a man in a high sense of the word... We shall look back upon his figure, we shall look back upon it as a figure which was that of a great Englishman, and we shall look back upon that figure with pride in our race.

- My own recollections of Calcutta incline to be a medley of only loosely connected impressions. A recognition of how much India has owed to Lord Curzon for the impulse that he gave to the preservation of her historical treasures, in part expressed in the Victoria Memorial.

- Lord Halifax, Fulness of Days (1957), p. 130

- Curzon is an intolerable person to do business with—pompous, dictatorial and outrageously conceited... Really he is an intolerable person, pig-headed, pompous and vindictive too! Yet an able, strong man with it all.

- Maurice Hankey, diary entry (12 May 1916), quoted in Stephen Roskill, Hankey, Man of Secrets: Volume I 1877–1919 (1970), pp. 271-272

- Curzon's tireless energy, inexhaustible industry and unique gift of setting out in proper perspective and with eloquence the facts of a complicated issue were an asset to the War Cabinet. What he lacked was resource in finding solutions to the problems which he could state so well, but this really mattered little because Lloyd George was himself resourceful. His little peculiarities—his pompous manner, ignorance (partly a pose) of democracy, and so forth—were a source of inexhaustible amusement to Lloyd George, who would listen with delight to any addition to the humorous stories and legends which grew up round Curzon during the war.

- Maurice Hankey, The Supreme Command 1914–1918, Volume Two (1961), p. 578

- The very epitome of snobbishness and embodiment of the exclusive hereditary principle.

- A. D. Harvey, Collision of Empires. Britain in Three World Wars, 1793–1945 (1994), p. 460

- A system whose ends were virtuous was beset by vices, most of them bureaucratic and racial. They were uncovered and vigorously dealt with by Lord Curzon, who arrived in Calcutta in January 1899. He was a man of vision who, unlike his predecessors, had wanted his position and came to it with an unequalled knowledge of Asian affairs. Curzon was certainly the most attractive and intelligent Viceroy, and India's best ruler under the British Raj. He was not an easy master in that he recognised and upbraided incompetence and procrastination.

- Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (1997), p. 315

- I had known Curzon for many years, had had him as a colleague at the India Office; had exchanged weekly letters with him ever since he became Viceroy, and had acquired a most sincere admiration for his very remarkable gifts. He was wonderfully well equipped for political success: he had a first-rate intellect, immense energy and industry; a genius for detail, a copious supply of fluent speech, and a most hearty and unfeigned interest in himself and his own career. He longed for power and pre-eminence, and was sincerely anxious to use them for what he believed to be good purposes; but he was equally anxious that his good deeds should be fully and conspicuously recognized. At no period of his life did he make the mistake of underrating himself.

- Lord Kilbracken, Reminiscences of Lord Kilbracken (1931), p. 180

- Lord Curzon lived in somewhat Olympian isolation and saw few members of the staff except his principal private secretary and the Permanent Under-Secretary. I never met him. But he was a superb drafter and exacted a high standard of accuracy and clarity from the departments. His minutes were models, often combining wit and malice... Whatever may be thought of British foreign policy at this time, there is no doubt that under Curzon and Crowe the machinery of the office was more efficient than it has ever been. But this was not achieved without effort. Curzon insisted not only on good work but on long hours.

- Ivone Kirkpatrick, The Inner Circle (1959), p. 33

- He has travelled a lot; he knows about the countries of the world. He has read a lot. He is full of knowledge which none of us possesses. He is useful in council. He is not a good executant and has no tact, but he is valuable for the reasons stated.

- David Lloyd George, remarks to George Riddell (1 October 1916), quoted in J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908–1923 (1986), p. 170

- I don't know about Curzon. He is very able, very just (he has never had sufficient credit for his Indian administration)[,] a great public servant, but he is not very accessible to new ideas.

- David Lloyd George, remarks to Lord Buckmaster recorded in C. P. Scott's diary (28 December 1917), quoted in The Political Diaries of C. P. Scott, 1911–1928, ed. Trevor Wilson (1970), p. 325

- The symbol of Empire in its noon-tide splendour.

- Nicholas Mansergh, The Commonwealth Experience (1969), p. 5

- A common idea of him is that of a strenuous and autocratic ruler, excelling in the domain of high policy and the maintenance of "Imperial" power, but out of sympathy with the needs and aspirations of the common people. To those who may have been infected by this prevalent misconception it will be a surprise to find that no Viceroy was ever more zealous for the welfare of the lowliest class of his subordinates, more ready to investigate and redress the grievance of any petitioner, however humble, or more resolutely determined to ensure justice to all the toiling millions submitted to his sway.

- Lord Milner, review of Lovat Fraser's India Under Curzon in The Times (3 October 1911), p. 8

- Lord Curzon is not a man towards whom it is possible to feel indifferent or neutral. On the one side were the men attracted or dominated by his superlative capacity, on the other those whom he had annoyed, or even alienated, by his trenchancy and "drive."

- Lord Milner, review of Lovat Fraser's India Under Curzon in The Times (3 October 1911), p. 8

- It is impossible to over-estimate the magnificent work Lord Curzon did for India in his constant care for its priceless archæological treasures.

- Lord Minto, letter to The Times (10 October 1911), p. 4

- After every other Viceroy has been forgotten, Curzon will be remembered because he restored all that was beautiful in India.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, remarks to Lord Swinton, quoted in Kenneth Rose, Superior Person: A Portrait of Curzon and his Circle in late Victorian England (1969), p. 339

- I really think now we shall leave on Sunday and with a Treaty... Of course it is entirely the Marquis [Curzon] absolutely entirely. When I thought he was wrong, he was right, and when I thought he was right, he was much righter than I thought. I give him 100 marks out of 100 and I am so proud of him. So awfully proud. He is a great man and one day England will know it.

But you see Britannia has ruled here. Entirely against the Turks, against treacherous allies, against a week-kneed cabinet, against a rotten public opinion—and Curzon has won. Thank God.- Harold Nicolson to Vita Sackville-West during the Lausanne Conference (1 February 1923), quoted in Vita and Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson, ed. Nigel Nicolson (1992), p. 120

- How striking...as evidence of the sane continuity of the English character, have been the universal tributes paid to the memory of Lord Curzon—a sense of national loss manifested in an almost unexpected outburst of national homage.

- Harold Nicolson, letter to The Spectator (4 April 1925), p. 556

- Courage, devotion, public service: the magnitude of England, the integrity of beauty, the glory of work; such were the ideals by which he achieved his victory, by which he triumphed over pain and tragedy and disappointment.

- Harold Nicolson, letter to The Spectator (4 April 1925), p. 556

- Lord Curzon...saved Mosul for Iraq. The methods by which he attained this object were characteristic of his unequalled diplomatic skill... In quiet tones Curzon embarked upon what was perhaps the most brilliant, the most erudite, the most lucid exposition which even he had ever achieved. With unemphatic logic he demolished one by one the arguments which Ismet Pasha had advanced. The whole resources of his unequalled knowledge, the whole value of his unexampled experience, the vigour of his superb memory, his supreme mastery of lucid diction, the perfect symmetry of his every phrase, combined with the visual effect of his Olympian presence, rendered his performance one which none of those present (and they were men who had been accustomed to oratory in every form) had ever seen equalled and would ever see surpassed. Even Mr. Washburn Child, who was all too apt to resent Lord Curzon's effortless superiority, was stirred. He records in his diary that the contrast between Ismet Pasha's statement and Lord Curzon's reply was as that "between a Greek temple and a dish of scrambled eggs".

- Harold Nicolson, Curzon: The Last Phase 1919–1925: A Study in Post-War Diplomacy (1934), pp. 332, 334

- We have some quaint prophecies in our Irish history that have an uncanny method of being realised, or seeming to be realised, in future history; and one of these, which rather surprised me, was told me by an Irishman the other day. It was that an old Irish prophetess prophecied that one day an Irishman would be found weeping over an Englishman's grave. To-day I, as an Irishman, weep over a great Englishman's grave.

- The expropriation, through the agency of our Courts and a rigid judicial system, of the Mohammedan peasantry in the West and North Punjab by their astute Hindu creditors of the towns and villages was already assuming serious dimensions, leading often to brutal acts of retaliation by the former, and threatening to become a serious political danger...

It was not till 1900, when the process of expropriation had gone to dangerous lengths, and fierce reprisals by the Mohammedan and even the Hindu peasantry made the situation grave beyond dispute, that Lord Curzon's Government carried through the Punjab Alienation of Land Act.

That beneficent measure was up to the end bitterly opposed by educated Indians, in the Press, on the platform, and in the Council. It is now regarded by hereditary landowners of all religions and castes as their "Magna Charta."- Michael O'Dwyer, India As I Knew It 1885–1925 (1925), pp. 38-39

- Whether in India or here at home, from first to last through a long and strenuous career, he set... and he followed, the highest possible standard of duty, of tireless and devoted industry... A great and unselfish servant of the State, who, in that service, was always ready to "scorn delights and live laborious days," a man who pursued high ambitions by none but worthy means, who never sulked under the rebuffs of fortune, who never allowed himself to be soured by the disappointment of unrealised hopes, he takes an assured place in the long line of those who have enriched by their gifts and dignified by their character the annals of English public life.

- We talked of Curzon. L. G. said he had great knowledge—information of a sort which is uncommon amongst British politicians. He knows foreign countries; he has travelled widely. He is dogmatic and often unreasonable, but he brings something to the general stock which is very valuable.

- George Riddell, diary entry (6 December 1916), quoted in Lord Riddell's War Diary, 1914–1918 (1933), p. 229

- He [David Lloyd George] again referred to Curzon's great knowledge, which is most valuable, he says. One day L. G. remarked to Balfour, "Curzon is always an object of wonder to me. I could sit and listen to him for hours. I sometimes ask myself whether I could speak as he does." "No," said Arthur Balfour, laughing, "of course you could not."

L. G.: Curzon's great defect is that he always feels that he is sitting on a golden throne, and must speak accordingly.- George Riddell, diary entry (10 December 1916), quoted in Lord Riddell's War Diary, 1914–1918 (1933), p. 230

- A pompous windbag.

- William Robertson, remarks to George Riddell (17 May 1917), quoted in J. M. McEwen (ed.), The Riddell Diaries 1908–1923 (1986), p. 189

- By any standard these two volumes [Persia and the Persian Question], totalling some 1300 pages are an extraordinary tour de force, the more so as Curzon knew no Persian and spent a comparatively short time in the country of which he only saw a small segment. Yet, this book embraces the whole of Persia, describing in fascinating and profound detail its history, antiquities, institutions, administration, finances, natural resources, commerce and topography with a thoroughness that no other writer on Persia, before or since, has achieved.

- Denis Wright, 'Curzon and Persia', The Geographical Journal, Vol. 153, No. 3 (November 1987), p. 345

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston on Wikipedia Media related to George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston on Wikimedia Commons

Categories:

- 1859 births

- 1925 deaths

- University of Oxford faculty

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

- Government ministers

- Conservative Party (UK) politicians

- Diplomats of the United Kingdom

- Viceroys of India

- University of Oxford alumni

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the British Academy

- Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs of Great Britain and the United Kingdom

- Leaders of the House of Lords (United Kingdom)

- Defence ministers of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom